Tea, Its History and Mystery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tea Drinking Culture in Russia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Hosei University Repository Tea Drinking Culture in Russia 著者 Morinaga Takako 出版者 Institute of Comparative Economic Studies, Hosei University journal or Journal of International Economic Studies publication title volume 32 page range 57-74 year 2018-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10114/13901 Journal of International Economic Studies (2018), No.32, 57‒74 ©2018 The Institute of Comparative Economic Studies, Hosei University Tea Drinking Culture in Russia Takako Morinaga Ritsumeikan University Abstract This paper clarifies the multi-faceted adoption process of tea in Russia from the seventeenth till nineteenth century. Socio-cultural history of tea had not been well-studied field in the Soviet historiography, but in the recent years, some of historians work on this theme because of the diversification of subjects in the Russian historiography. The paper provides an overview of early encounters of tea in Russia in the sixteenth and seventeenth century, comparing with other beverages that were drunk at that time. The paper sheds light on the two supply routes of tea to Russia, one from Mongolia and China, and the other from Europe. Drinking of brick tea did not become a custom in the 18th century, but tea consumption had bloomed since 19th century, rapidly increasing the import of tea. The main part of the paper clarifies how Russian- Chines trade at Khakhta had been interrelated to the consumption of tea in Russia. Finally, the paper shows how the Russian tea culture formation followed a different path from that of the tea culture of Europe. -

Identification of Similar Chinese Congou Black Teas Using An

molecules Article Identification of Similar Chinese Congou Black Teas Using an Electronic Tongue Combined with Pattern Recognition Danyi Huang , Zhuang Bian, Qinli Qiu, Yinmao Wang, Dongmei Fan and Xiaochang Wang * Tea Research Institute, Zhejiang University, # 866 Yuhangtang Road, Hangzhou 310058, China; [email protected] (D.H.); [email protected] (Z.B.); [email protected] (Q.Q.); [email protected] (Y.W.); [email protected] (D.F.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-0571-8898-2380 Received: 8 November 2019; Accepted: 6 December 2019; Published: 12 December 2019 Abstract: It is very difficult for humans to distinguish between two kinds of black tea obtained with similar processing technology. In this paper, an electronic tongue was used to discriminate samples of seven different grades of two types of Chinese Congou black tea. The type of black tea was identified by principal component analysis and discriminant analysis. The latter showed better results. The samples of the two types of black tea distributed on the two sides of the region graph were obtained from discriminant analysis, according to tea type. For grade discrimination, we determined grade prediction models for each tea type by partial least-squares analysis; the coefficients of determination of the prediction models were both above 0.95. Discriminant analysis separated each sample in region graph depending on its grade and displayed a classification accuracy of 98.20% by cross-validation. The back-propagation neural network showed that the grade prediction accuracy for all samples was 95.00%. Discriminant analysis could successfully distinguish tea types and grades. As a complement, the models of the biochemical components of tea and electronic tongue by support vector machine showed good prediction results. -

A Russian Tea Wedding an Interview with Katya & Denis

Voices from the Hut A Russian Tea Wedding An Interview with Katya & Denis This growing community often blows our hearts wide open. It is the reason we feel so inspired to publish these magazines, build centers and host tea ceremonies: tea family! Connection between hearts is going to heal this world, one bowl at a time... Katya & Denis are tea family to us all, and so let’s share in the occasion and be distant witnesses at their beautiful tea wedding! 茶道 ne of the things we love the imagine this continuing in so many dinner, there was a party for the Bud- O most about Global Tea Hut is beautiful ways! dhists on the tour and Denis invited the growing community, and all the We very much want to foster Katya to share some puerh with him. beautiful family we’ve made through community here, and way beyond It was the first time she’d ever tried tea. As time passes, this aspect of be- just promoting our tea tradition. It such tea, and she loved it from the ing here, sharing tea with all of you, doesn’t matter if you practice tea in first sip. Then, in 2010, Katya moved starts to grow. New branches sprout our tradition or not, we’re family—in from her birthplace in Siberia, every week, and we hear about new our love for tea, Mother Earth and Komsomolsk-na-Amure, to Moscow and amazing ways that members are each other! If any of you have any to live with Denis (her hometown is connecting to each other. -

What Every Dentist Should Know About Tea

Nutrition What every dentist should know about tea Moshe M. Rechthand n Judith A. Porter, DDS, EdD, FICD n Nasir Bashirelahi, PhD Tea is one of the most frequently consumed beverages in the world, of drinking tea, as well as the potential negative aspects of tea second only to water. Repeated media coverage about the positive consumption. health benefits of tea has renewed interest in the beverage, particularly Received: August 23, 2013 among Americans. This article reviews the general and specific benefits Accepted: October 1, 2013 ea has been a staple of Chinese life for their original form.4 Epigallocatechin-3- known as reactive oxygen species (ROS) so long that it is considered to be 1 of galate (EGCG) is the principal bioactive are formed through normal aerobic cellular Tthe 7 necessities of Chinese culture.1 catechin left intact in green tea and the metabolism. During this process, oxygen is The popularity of tea should come as no one responsible for many of its health partially reduced to form a reactive radical surprise considering the recent studies benefits.3 By contrast, black tea is fully as a byproduct in the formation of water. conducted confirming tea’s remarkable oxidized/fermented during processing, ROS are helpful to the body because they health benefits.2,3 The drinking of tea dates which accounts for both its stronger flavor assist in the degradation of microbial back to the third millenium BCE, when and the fact that its catechin content is disease.5 However, ROS also contain free Shen Nong, the famous Chinese emperor lower than the other teas.2 Black tea’s fer- radical electrons that can wreak havoc on and herbalist, discovered the special brew. -

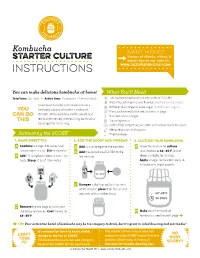

Instructions for Making Kombucha

Kombucha Want more? Dozens of eBooks, videos, & starter culture expert tips on our website: www.culturesforhealth.com Instructions m R You can make delicious kombucha at home! What You’ll Need Total time: 30+ days _ Active time: 15 minutes + 1 minute daily 1 dehydrated kombucha starter culture (SCOBY) Water free of chlorine and fluoride (bottled spring water) A kombucha starter culture consists of a sugar White or plain organic cane sugar (avoid harsh sugars) symbiotic colony of bacteria and yeast you Plain, unflavored black tea, loose or in bags (SCOBY). When combined with sweetened can do Distilled white vinegar tea and fermented, the resulting kombucha this 1 quart glass jar beverage has a tart zing. Coffee filter or tight-weave cloth and rubber band to secure Measuring cups and spoons Activating the SCOBY Thermometer 1. make sweet tea 2. add the scoby and vinegar 3. culture your kombucha A Combine 2-3 cups hot water and G Allow the mixture to > >D Add 1/2 cup vinegar to the cool tea. > culture 1/4 cup sugar in a jar. Stir to dissolve. undisturbed at 68°-85°F, out of >E Add the dehydrated SCOBY to the B 11/2 teaspoons loose tea or 2 tea direct sunlight, for 30 days. > Add tea mixture. bags. Steep at least 10 minutes. Apply vinegar to the cloth daily to help prevent mold growth. sugar 1/2 1/4 c. c. 68°-85°F 2-3 c. 2 F Dampen a cloth or coffee filter with > white vinegar; place it on the jar and secure it with a rubber band. -

Teahouses and the Tea Art: a Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives Teahouses and the Tea Art: A Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition LI Jie Master's Thesis in East Asian Culture and History (EAST4591 – 60 Credits – Autumn 2015) Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages Faculty of Humanities UNIVERSITY OF OSLO 24 November, 2015 © LI Jie 2015 Teahouses and the Tea Art: A Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition LI Jie http://www.duo.uio.no Print: University Print Center, University of Oslo II Summary The subject of this thesis is tradition and the current trend of tea culture in China. In order to answer the following three questions “ whether the current tea culture phenomena can be called “tradition” or not; what are the changes in tea cultural tradition and what are the new features of the current trend of tea culture; what are the endogenous and exogenous factors which influenced the change in the tea drinking tradition”, I did literature research from ancient tea classics and historical documents to summarize the development history of Chinese tea culture, and used two month to do fieldwork on teahouses in Xi’an so that I could have a clear understanding on the current trend of tea culture. It is found that the current tea culture is inherited from tradition and changed with social development. Tea drinking traditions have become more and more popular with diverse forms. -

Assessment of Kombucha Tea Recipe and Food Safety Plan

Environmental Health Services FFoooodd IIssssuuee Notes from the Field Food Safety Assessment of Kombucha Tea Recipe and Food Safety Plan Request received from: Regional Health Authority Date of request: January 27, 2015. Updated March 9, 2020. Issue (brief description): Assessment of kombucha tea recipe and food safety plan Disclaimer: The information provided in this document is based on the judgement of BCCDC’s Environmental Health Services Food Safety Specialists and represents our knowledge at the time of the request. It has not been peer-reviewed and is not comprehensive. Summary of search information: 1. Internet sources: general search for “kombucha” 2. OVID and PubMed search “kombucha” AND “illness” 3. Personal communication with federal and provincial agencies Background information: Kombucha Tea (KT, sometimes called Manchurian tea or Kargasok tea) is a slightly sweet, mildy acidic tea beverage consumed worldwide, which has seen significant sales growth in North American markets from recent years.1 KT is prepared by fermenting sweetened black or green tea preparations with a symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast (SCOBY), often referred to as the “mushroom” (misnamed because of its appearance) or as a “mother” (for its ability to reproduce). The floating mat is a biofilm layer made up of bacteria and cellulose that is more correctly referred to as a pellicle. The culture comes in different varieties, but is generally made up of a variable amount of Gluconacetobacter, Lactobacillus, and Acetobacter (genera of acetic acid bacteria) -

House Specials : Original Blend Teas

House Specials : Original House Specials : Original Blend Teas <Black> Blend Teas <Green > Lavegrey: Jasmine Honey: Our unique Creamy Earl Grey + relaxing Lavender. Jasmine green tea + honey. One of the most popular Hint of vanilla adds a gorgeous note to the blend. ways to drink jasmine tea in Asia. Enjoy this sweet joyful moment. Jasmine Mango: London Mist Jasmine + Blue Mango green tea. Each tea is tasty in Classic style tea: English Breakfast w/ cream + their own way and so is their combination! honey. Vanilla added to sweeten your morning. Strawberry Mango: Lady’s Afternoon Blue Mango with a dash of Strawberry fusion. Great Another way to enjoy our favorite Earl Grey. Hints combination of sweetness and tartness that you can of Strawberry and lemon make this blend a perfect imagine. afternoon tea! Green Concussion: Irish Cream Cherry Dark Gun Powder Green + Matcha + Peppermint Sweet cherry joyfully added to creamy yet stunning give you a little kick of caffeine. This is a crisp blend Irish Breakfast tea. High caffeine morning tea. of rare compounds with a hidden tropical fruit. Majes Tea On Green: Natural Raspberry black tea with a squeeze of lime Ginger green tea + fresh ginger and a dash of honey to add tanginess after taste. to burn you calories. Pomeberry I M Tea: Pomegranate black tea with your choice of adding Special blend for Cold & Flu prevention. Sencha, Blackberry or Strawberry flavoring. Lemon Balm and Spearmint mix help you build up your immunity. Minty Mint Mint black tea with Peppermint. A great refreshing Mango Passion: drink for a hot summer day. -

Notes on the History of Tea

Notes on the History of Tea It is surprising how incomplete our knowledge is. We are all aware that we import coffee from tropical America. But where do we obtain our tea? What is tea? From what plant does it come? How long have we been drinking it? All these questions passed through my mind as I read the manuscript of the pre- ceding article. To answer some of my questions, and yours, I gathered together the following notes. The tea of commerce consists of the more or less fermented, rolled and dried immature leaves of Camellia sinensis. There are two botanical varieties of the tea plant. One, var. sinensis, the original chinese tea, is a shrub up to 20 feet tall, native in southern and western Yunnan, spread by cultivation through- out southern and central China, and introduced by cultivation throughout the warm temperate regions of the world. The other, var. assamica, the Assam tea, is a forest tree, 60 feet or more tall, native in the area between Assam and southern China. Var. sinensis is apparently about as hardy as Camellia japonica (the common Camellia). The flowers are white, nodding, fra- grant, and produced variously from June to January, but usually in October. The name is derived from the chinese Te. An alter- nate chinese name seems to be cha, which passed into Hindi and Arabic as chha, anglicized at an early date as Chaw. The United States consumes about 115 million pounds of tea annually. The major tea exporting countries are India, Ceylon, Japan, Indonesia, and the countries of eastern Africa. -

Japanese Tea Ceremony: How It Became a Unique Symbol of the Japanese Culture and Shaped the Japanese Aesthetic Views

International J. Soc. Sci. & Education 2021 Vol.11 Issue 1, ISSN: 2223-4934 E and 2227-393X Print Japanese Tea Ceremony: How it became a unique symbol of the Japanese culture and shaped the Japanese aesthetic views Yixiao Zhang Hangzhou No.2 High School of Zhejiang Province, CHINA. [email protected] ABSTRACT In the process of globalization and cultural exchange, Japan has realized a host of astonishing achievements. With its unique cultural identity and aesthetic views, Japan has formed a glamorous yet mysterious image on the world stage. To have a comprehensive understanding of Japanese culture, the study of Japanese tea ceremony could be of great significance. Based on the historical background of Azuchi-Momoyama period, the paper analyzes the approaches Sen no Rikyu used to have the impact. As a result, the impact was not only on the Japanese tea ceremony itself, but also on Japanese culture and society during that period and after.Research shows that Tea-drinking was brought to Japan early in the Nara era, but it was not integrated into Japanese culture until its revival and promotion in the late medieval periods under the impetus of the new social and religious realities of that age. During the Azuchi-momoyama era, the most significant reform took place; 'Wabicha' was perfected by Takeno Jouo and his disciple Sen no Rikyu. From environmental settings to tea sets used in the ritual to the spirit conveyed, Rikyu reregulated almost all aspects of the tea ceremony. He removed the entertaining content of the tea ceremony, and changed a rooted aesthetic view of Japanese people. -

Empire of Tea

Empire of Tea Empire of Tea The Asian Leaf that Conquered the Wor ld Markman Ellis, Richard Coulton, Matthew Mauger reaktion books For Ceri, Bey, Chelle Published by Reaktion Books Ltd 33 Great Sutton Street London ec1v 0dx, uk www.reaktionbooks.co.uk First published 2015 Copyright © Markman Ellis, Richard Coulton, Matthew Mauger 2015 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers Printed and bound in China by 1010 Printing International Ltd A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 978 1 78023 440 3 Contents Introduction 7 one: Early European Encounters with Tea 14 two: Establishing the Taste for Tea in Britain 31 three: The Tea Trade with China 53 four: The Elevation of Tea 73 five: The Natural Philosophy of Tea 93 six: The Market for Tea in Britain 115 seven: The British Way of Tea 139 eight: Smuggling and Taxation 161 nine: The Democratization of Tea Drinking 179 ten: Tea in the Politics of Empire 202 eleven: The National Drink of Victorian Britain 221 twelve: Twentieth-century Tea 247 Epilogue: Global Tea 267 References 277 Bibliography 307 Acknowledgements 315 Photo Acknowledgements 317 Index 319 ‘A Sort of Tea from China’, c. 1700, a material survival of Britain’s encounter with tea in the late seventeenth century. e specimen was acquired by James Cuninghame, a physician and ship’s surgeon who visited Amoy (Xiamen) in 1698–9 and Chusan (Zhoushan) in 1700–1703. -

Glossary of Tea Terms Agony of the Leaves This Is a Description of the Relaxation of Curled Leaves During Steeping

Glossary of Tea Terms Agony of the leaves This is a description of the relaxation of curled leaves during steeping. Anhui The major black tea producing regions in China. Aroma The characteristic fragrance of brewed tea, imparted by its essential oils. Assam A type of tea grown in the state of Assam, India, known for its strong, deep red brewed color. Astringent A term describing the dry taste in the mouth left by teas high in unoxidized polyphenols. Autumnal A term describing tea harvested late in the growing season. Bakey A tea taster expression for overfired teas Bergamot An essential oil of the bergamot orange used to flavor a black tea base to make Earl Grey tea Billy An Australian term referring to tin pot with wire handle to suspend over an open fire in which tea is boiled Biscuity Green tea leaves that have been oxidized, or fermented, imparting a characteristic reddish brew. The most common type of tea worldwide. Black Tea prepared from green tea leaves which have been allowed to oxidize, or ferment, to form a reddish brew. Blend A mixture of teas, usually to promote consistency between growing seasons Bloom Used to describe sheen or lustre present to finished leaf Body A term to denote a full strength brew Bold Describes large leaf cut tea Brassy An unpleasant acidic bite from improperly withered tea Break An auction term describing a tea lot for sale, usually at least 18 chests. Brick tea Tea leaves that have been steamed and compressed into bricks. The bricks are shaved and brewed with butter and salt and then served as a soup.