Title: a Puzzle Assembled Carrie Gongaware Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planetary Geologic Mappers Annual Meeting

Program Lunar and Planetary Institute 3600 Bay Area Boulevard Houston TX 77058-1113 Planetary Geologic Mappers Annual Meeting June 12–14, 2018 • Knoxville, Tennessee Institutional Support Lunar and Planetary Institute Universities Space Research Association Convener Devon Burr Earth and Planetary Sciences Department, University of Tennessee Knoxville Science Organizing Committee David Williams, Chair Arizona State University Devon Burr Earth and Planetary Sciences Department, University of Tennessee Knoxville Robert Jacobsen Earth and Planetary Sciences Department, University of Tennessee Knoxville Bradley Thomson Earth and Planetary Sciences Department, University of Tennessee Knoxville Abstracts for this meeting are available via the meeting website at https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/pgm2018/ Abstracts can be cited as Author A. B. and Author C. D. (2018) Title of abstract. In Planetary Geologic Mappers Annual Meeting, Abstract #XXXX. LPI Contribution No. 2066, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston. Guide to Sessions Tuesday, June 12, 2018 9:00 a.m. Strong Hall Meeting Room Introduction and Mercury and Venus Maps 1:00 p.m. Strong Hall Meeting Room Mars Maps 5:30 p.m. Strong Hall Poster Area Poster Session: 2018 Planetary Geologic Mappers Meeting Wednesday, June 13, 2018 8:30 a.m. Strong Hall Meeting Room GIS and Planetary Mapping Techniques and Lunar Maps 1:15 p.m. Strong Hall Meeting Room Asteroid, Dwarf Planet, and Outer Planet Satellite Maps Thursday, June 14, 2018 8:30 a.m. Strong Hall Optional Field Trip to Appalachian Mountains Program Tuesday, June 12, 2018 INTRODUCTION AND MERCURY AND VENUS MAPS 9:00 a.m. Strong Hall Meeting Room Chairs: David Williams Devon Burr 9:00 a.m. -

Back Matter (PDF)

Index Page numbers in italics refer to Tables or Figures Acasta gneiss 137, 138 Chladni, Ernst 94, 97 Adam, Robert 8, 11 chlorite 70, 71 agriculture, Hutton on 177 chloritoid stability 70 Albritton, Claude C. 100 Clerk Jnr, John 3 alumina (A1203), reaction in metamorphism 67-71 Clerk of Odin, John 5, 6, 7, 10, 11 andalusite stability 67 Clerk-Maxwell, George 10 anthropic principle 79-80 climate change 142 Apex basalt 140 Lyell on 97-8 Archean cratons (archons) 28, 31-2 coal as Earth heat source 176 Arizona Crater 98-9 coesite stability 65 Arran, Isle of 170 Columbia River basalts 32 asthenosphere 22 comets 89-90, 147-8 astrobleme 101 short v. long period 92 atmospheric composition 83-6 as source of life 148-9 Austral Volcanic Chain 24 continental flood basalt (CFB) 20, 23, 32 cordierite stability 67 craters, impact Bacon, Francis 21 Chixulub 109, 110, 143 Baldwin, Ralph 102 early ideas on 90, 98 Banks, Sir Joseph 96 modern occurrences 91, 98-101 Barringer, Daniel Moreau 99 Morokweng 142 Barringer Crater 99, 102, 103 modern research 102-3 basalt periodicity of 111-12 described by Hall 40-1 creation, Hutton's views on 76 mid-ocean ridge (MORB) 16-17, 20-1, 22, 23, 30-1 Creech, William 5 modern experiments on 44-7 Cretaceous-Tertiary impacts 141 ocean island (OIB) 20, 23 crust formation 17 see also flood basalt cryptoexplosion structures 101 Benares (India) meteorite shower 96 cryptovolcanic structures 100-1 Biot, Jean-Baptiste 97 Black, Joseph 4, 9, 10, 11, 42, 171 Boon, John D. -

Exploring Comets and Modeling for Mission Success

Exploring Comets and Modeling for Mission Success National Science Education Standards Alignment Created for Deep Impact, A NASA Discovery mission Maura Rountree-Brown and Art Hammon Educator-Enrichment Grades 5 – 8 Science as Inquiry Abilities necessary to do scientific inquiry − Identify questions that can be answered through scientific investigations. • Exploring Comets: Reflections on comets, missions and modeling − Develop descriptions, explanations, predictions, and models using evidence. • Make a Comet and Eat It!, Chemistry and Thermodynamics of Ice Cream, Comet on a Stick, Paper Comet with a Deep Impact, and Comet Models Based on the Deep Impact Mission − Think critically and logically to make the relationships between evidence and explanations. • Make a Comet and Eat It!, Comet on a Stick, Paper Comet with a Deep Impact, and Comet Models Based on the Deep Impact Mission − Communicate scientific procedures and explanations. • Make a Comet and Eat It! Understandings about scientific inquiry − Different kinds of questions suggest different kinds of scientific investigations. Some investigations involve observing and describing objects, or events; some involve experiments; some involve seeking more information; some involve discovery of new objects and phenomena; and some involve making models. • Make a Comet and Eat It!, Chemistry and Thermodynamics of Ice Cream, Comet on a Stick, Paper Comet with a Deep Impact, Comet Models Based on the Deep Impact Mission, and Deep Impact Comet Modeling − Current scientific knowledge and understanding guide scientific investigations. Different scientific domains employ different methods, core theories, and standards to advance scientific knowledge and understanding. • A Comet’s Place in the Solar System, Exploring Comets: Reflections on comets, missions and modeling, Deep Impact Comet Modeling, Deep Impact: Interesting Comet Facts, and Small Bodies Missions − Scientific explanations emphasize evidence, have logically consistent arguments, and use scientific principles, models, and theories. -

16. Ice in the Martian Regolith

16. ICE IN THE MARTIAN REGOLITH S. W. SQUYRES Cornell University S. M. CLIFFORD Lunar and Planetary Institute R. O. KUZMIN V.I. Vernadsky Institute J. R. ZIMBELMAN Smithsonian Institution and F. M. COSTARD Laboratoire de Geographie Physique Geologic evidence indicates that the Martian surface has been substantially modified by the action of liquid water, and that much of that water still resides beneath the surface as ground ice. The pore volume of the Martian regolith is substantial, and a large amount of this volume can be expected to be at tem- peratures cold enough for ice to be present. Calculations of the thermodynamic stability of ground ice on Mars suggest that it can exist very close to the surface at high latitudes, but can persist only at substantial depths near the equator. Impact craters with distinctive lobale ejecta deposits are common on Mars. These rampart craters apparently owe their morphology to fluidhation of sub- surface materials, perhaps by the melting of ground ice, during impact events. If this interpretation is correct, then the size frequency distribution of rampart 523 524 S. W. SQUYRES ET AL. craters is broadly consistent with the depth distribution of ice inferred from stability calculations. A variety of observed Martian landforms can be attrib- uted to creep of the Martian regolith abetted by deformation of ground ice. Global mapping of creep features also supports the idea that ice is present in near-surface materials at latitudes higher than ± 30°, and suggests that ice is largely absent from such materials at lower latitudes. Other morphologic fea- tures on Mars that may result from the present or former existence of ground ice include chaotic terrain, thermokarst and patterned ground. -

In Pdf Format

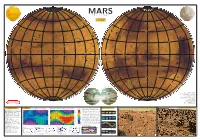

lós 1877 Mik 88 ge N 18 e N i h 80° 80° 80° ll T 80° re ly a o ndae ma p k Pl m os U has ia n anum Boreu bal e C h o A al m re u c K e o re S O a B Bo l y m p i a U n d Planum Es co e ria a l H y n d s p e U 60° e 60° 60° r b o r e a e 60° l l o C MARS · Korolev a i PHOTOMAP d n a c S Lomono a sov i T a t n M 1:320 000 000 i t V s a Per V s n a s l i l epe a s l i t i t a s B o r e a R u 1 cm = 320 km lkin t i t a s B o r e a a A a A l v s l i F e c b a P u o ss i North a s North s Fo d V s a a F s i e i c a a t ssa l vi o l eo Fo i p l ko R e e r e a o an u s a p t il b s em Stokes M ic s T M T P l Kunowski U 40° on a a 40° 40° a n T 40° e n i O Va a t i a LY VI 19 ll ic KI 76 es a As N M curi N G– ra ras- s Planum Acidalia Colles ier 2 + te . -

Appendix a Recovery of Ejecta Material from Confirmed, Probable

Appendix A Recovery of Ejecta Material from Confirmed, Probable, or Possible Distal Ejecta Layers A.1 Introduction In this appendix we discuss the methods that we have used to recover and study ejecta found in various types of sediment and rock. The processes used to recover ejecta material vary with the degree of lithification. We thus discuss sample processing for unconsolidated, semiconsolidated, and consolidated material separately. The type of sediment or rock is also important as, for example, carbonate sediment or rock is processed differently from siliciclastic sediment or rock. The methods used to take and process samples will also vary according to the objectives of the study and the background of the investigator. We summarize below the methods that we have found useful in our studies of distal impact ejecta layers for those who are just beginning such studies. One of the authors (BPG) was trained as a marine geologist and the other (BMS) as a hard rock geologist. Our approaches to processing and studying impact ejecta differ accordingly. The methods used to recover ejecta from unconsolidated sediments have been successfully employed by BPG for more than 40 years. A.2 Taking and Handling Samples A.2.1 Introduction The size, number, and type of samples will depend on the objective of the study and nature of the sediment/rock, but there a few guidelines that should be followed regardless of the objective or rock type. All outcrops, especially those near industrialized areas or transportation routes (e.g., highways, train tracks) need to be cleaned off (i.e., the surface layer removed) prior to sampling. -

Extrasolar Kuiper Belt Dust Disks 465

Moro-Martín et al.: Extrasolar Kuiper Belt Dust Disks 465 Extrasolar Kuiper Belt Dust Disks Amaya Moro-Martín Princeton University Mark C. Wyatt University of Cambridge Renu Malhotra and David E. Trilling University of Arizona The dust disks observed around mature stars are evidence that plantesimals are present in these systems on spatial scales that are similar to that of the asteroids and the Kuiper belt ob- jects (KBOs) in the solar system. These dust disks (a.k.a. “debris disks”) present a wide range of sizes, morphologies, and properties. It is inferred that their dust mass declines with time as the dust-producing planetesimals get depleted, and that this decline can be punctuated by large spikes that are produced as a result of individual collisional events. The lack of solid-state fea- tures indicate that, generally, the dust in these disks have sizes >10 µm, but exceptionally, strong silicate features in some disks suggest the presence of large quantities of small grains, thought to be the result of recent collisions. Spatially resolved observations of debris disks show a di- versity of structural features, such as inner cavities, warps, offsets, brightness asymmetries, spirals, rings, and clumps. There is growing evidence that, in some cases, these structures are the result of the dynamical perturbations of a massive planet. Our solar system also harbors a debris disk and some of its properties resemble those of extrasolar debris disks. From the cratering record, we can infer that its dust mass has decayed with time, and that there was at least one major “spike” in the past during the late heavy bombardment. -

Thirty Meter Telescope Detailed Science Case: 2015

TMT.PSC.TEC.07.007.REL02 PAGE 1 DETAILEDThirty SCIENCE CASE: Meter 2015 TelescopeApril 29, 2015 Detailed Science Case: 2015 International Science Development Teams & TMT Science Advisory Committee TMT.PSC.TEC.07.007.REL02 PAGE I DETAILED SCIENCE CASE: 2015 April 29, 2015 Front cover: Shown is the Thirty Meter Telescope during nightime operations using the Laser Guide Star Facility (LGSF). The LGSF will create an asterism of stars, each asterism specifically chosen according to the particular adaptive optics system being used and the science program being conducted. TMT.PSC.TEC.07.007.REL02 PAGE II DETAILED SCIENCE CASE: 2015 April 29, 2015 DETAILED SCIENCE CASE: 2015 TMT.PSC.TEC.07.007.REL02 1 DATE: (April 29, 2015) Low resolution version Full resolution version available at: http://www.tmt.org/science-case © Copyright 2015 TMT Observatory Corporation arxiv.org granted perpetual, non-exclusive license to distribute this article 1 Minor revisions made 6/3/2015 to correct spelling, acknowledgements and references TMT.PSC.TEC.07.007.REL02 PAGE III DETAILED SCIENCE CASE: 2015 April 29, 2015 PREFACE For tens of thousands of years humans have looked upward and tried to find meaning in what they see in the sky, trying to understand the context in which they and their world exists. Consequently, astronomy is the oldest of the sciences. Since Aristotle began systematically recording the motions of the planets and formulating the first models of the universe there have been over 2350 years of scientific study of the sky. The earliest scientists explained their observations with the earth-centered universe model and little more than two millennia later we now live in an age where we are beginning to characterize exoplanets and systematically probing the evolution of the universe from its earliest moments to the present day. -

Meteorite Impacts, Earth, and the Solar System

Traces of Catastrophe A Handbook of Shock-Metamorphic Effects in Terrestrial Meteorite Impact Structures Bevan M. French Research Collaborator Department of Mineral Sciences, MRC-119 Smithsonian Institution Washington DC 20560 LPI Contribution No. 954 i Copyright © 1998 by LUNAR AND PLANETARY INSTITUTE The Institute is operated by the Universities Space Research Association under Contract No. NASW-4574 with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Material in this volume may be copied without restraint for library, abstract service, education, or personal research purposes; however, republication of any portion thereof requires the written permission of the Insti- tute as well as the appropriate acknowledgment of this publication. Figures 3.1, 3.2, and 3.5 used by permission of the publisher, Oxford University Press, Inc. Figures 3.13, 4.16, 4.28, 4.32, and 4.33 used by permission of the publisher, Springer-Verlag. Figure 4.25 used by permission of the publisher, Yale University. Figure 5.1 used by permission of the publisher, Geological Society of America. See individual captions for reference citations. This volume may be cited as French B. M. (1998) Traces of Catastrophe:A Handbook of Shock-Metamorphic Effects in Terrestrial Meteorite Impact Structures. LPI Contribution No. 954, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston. 120 pp. This volume is distributed by ORDER DEPARTMENT Lunar and Planetary Institute 3600 Bay Area Boulevard Houston TX 77058-1113, USA Phone:281-486-2172 Fax:281-486-2186 E-mail:[email protected] Mail order requestors will be invoiced for the cost of shipping and handling. Cover Art.“One Minute After the End of the Cretaceous.” This artist’s view shows the ancestral Gulf of Mexico near the present Yucatán peninsula as it was 65 m.y. -

The Surface of Mars 1. Cratered Terrains

VOL. 76, NO. 2 JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH JANUARY 10, 1971 The Surface of Mars i. Cratered Terrains • BRUCEC. MURRAY,LAURENCE A. SODERBLOM, ROBERTP. SHARP,AND JAMESA. CUTTS Division of GeologicalSciences California Institute of Technology,Pasadena 91109 Mariner 6 and 7 pictures show that craters are the dominant landform on Mars and that their occurrenceis not correlated uniquely with latitude, elevation, or albedo markings. Two distinct morphological classesare recognized: small bowl-shaped and large flat-bottomed. The former showlittle evidenceof modifications,whereas the latter appear generally more modified than hmar upland cratersof comparablesize. A regionalmaria/uplands dichotomylike the moon has not yet been recognized on Mars. Crater modification on Mars has involved much greater horizontal redistribution of material than in the lunar uplands. It is possiblethat there are erosionalprocesses only infrequently active. Analysisof the natures and fluxesof bodiesthat have probably impacted the moon and Mars leads to the likelihood that most of the large flat-bottomed craters on Mars have survived from the final phasesof planetary accretion. Significant crater modification, how- ever, has taken place more recently on Mars. Inasmuch as the present small bowl-shaped craters evidence little modification, the postaccretion crater-modification processon Mars may have been primarily episodic rather than continuous. The size-frequency distribution of impacting bodiesthat produced the present small Martian bowl-shapedcraters differs from that responsible for post-mare primary impacts on the moon by a marked deficiency of large bodies. Survival of crater topography from the end of planetary accretion would make any hypothetical earthlike phasewith primitive oceansthere unlikely. The traditional view of Mars as an earthlike planetary neighbor in terms of its surface history is not supported by the picture data. -

Guiding Visions of the Space Age

GUIDING VISIONS OF THE SPACE AGE: HOW IMAGINATIVE EXPECTATIONS DIRECTED AN INDUSTRY by Daniel Waymark Goodman A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2019 ©COPYRIGHT by Daniel Waymark Goodman 2019 All Rights Reserved ii To Annie, For your unending love, support and patience. “With a bad telescope and a powerful imagination, there is no saying what you may not accomplish.” H. G. Wells, 1898 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am enormously grateful for the support of a network of brilliant faculty and friends at Montana State University’s Department of History and Philosophy. I am especially privileged to have had the constant guidance of Dr. Michael Reidy over the last two years. Michael, this project could not have happened without your mentorship, critical eye and insights. I am deeply indebted to have had your support and friendship. I am also hugely thankful to have had the guidance of Dr. Brett Walker and Dr. Timothy LeCain. Brett, you taught me new ways of approaching history that have reshaped my worldview. Tim, in enhancing my understanding of my own country’s history, you provided me much of the context I needed for this project. I also owe a debt of gratitude to Dr. Billy Smith and Dr. James Meyer for greatly advancing my skills as a writer and thinker. You both pushed me again and again, and I am glad you did. Additionally, to the friendly staff at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum archives in Chantilly, Virginia, thanks for all of your help providing me ample sources for this research as well as future projects. -

Impact Craters on Pluto and Charon Indicate a Deficit of Small Kuiper Belt Objects

Impact Craters on Pluto and Charon Indicate a Deficit of Small Kuiper Belt Objects K. N. Singer1*, W. B. McKinnon2, B. Gladman3, S. Greenstreet4, E. B. Bierhaus5, S. A. Stern1, A. H. Parker1, S. J. Robbins1, P. M. Schenk6, W. M. Grundy7, V. J. Bray8, R. A. Beyer9,10, R. P. Binzel11, H. A. Weaver12, L. A. Young1, J. R. Spencer1, J. J. Kavelaars13, J. M. Moore10, A. M. Zangari1, C. B. Olkin1, T. R. Lauer14, C. M. Lisse12, K. Ennico10, New Horizons Geology, Geophysics and Imaging Science Theme Team†, New Horizons Surface Composition Science Theme Team†, New Horizons Ralph and LORRI Teams†. Published 1 March 2019, Science 363, 955 (2019) DOI: 10.1126/science.aap8628 1Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, CO 80302, USA. 2Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences and McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences, Washington University, St. Louis, MO 63130, USA. 3University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada. 4Las Cumbres Observatory, Goleta, CA 93117, USA, and the University of California, Santa Barbara, CA, 93106 USA. 5Lockheed Martin Space Systems Company, Denver, CO 80127, USA. 6Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston, TX 77058, USA. 7Lowell Observatory, Flagstaff, AZ 86001, USA. 8University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA. 9Carl Sagan Center at the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) Institute, Mountain View, CA 94043, USA. 10National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Ames Research Center, Space Science Division, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA. 11Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA. 12Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, Laurel, MD 20723, USA. 13National Research Council of Canada, Victoria, BC, Canada. 14National Optical Astronomy Observatory, Tucson, AZ 26732, USA.