Dentalmorphology622mcgr.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

UNDERSTANDING CARNIVORAN ECOMORPHOLOGY THROUGH DEEP TIME, WITH A CASE STUDY DURING THE CAT-GAP OF FLORIDA By SHARON ELIZABETH HOLTE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2018 © 2018 Sharon Elizabeth Holte To Dr. Larry, thank you ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my family for encouraging me to pursue my interests. They have always believed in me and never doubted that I would reach my goals. I am eternally grateful to my mentors, Dr. Jim Mead and the late Dr. Larry Agenbroad, who have shaped me as a paleontologist and have provided me to the strength and knowledge to continue to grow as a scientist. I would like to thank my colleagues from the Florida Museum of Natural History who provided insight and open discussion on my research. In particular, I would like to thank Dr. Aldo Rincon for his help in researching procyonids. I am so grateful to Dr. Anne-Claire Fabre; without her understanding of R and knowledge of 3D morphometrics this project would have been an immense struggle. I would also to thank Rachel Short for the late-night work sessions and discussions. I am extremely grateful to my advisor Dr. David Steadman for his comments, feedback, and guidance through my time here at the University of Florida. I also thank my committee, Dr. Bruce MacFadden, Dr. Jon Bloch, Dr. Elizabeth Screaton, for their feedback and encouragement. I am grateful to the geosciences department at East Tennessee State University, the American Museum of Natural History, and the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard for the loans of specimens. -

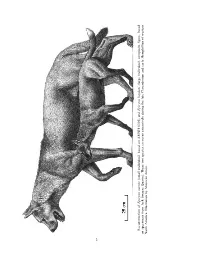

PHYLOGENETIC SYSTEMATICS of the BOROPHAGINAE (CARNIVORA: CANIDAE) Xiaoming Wang

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Mammalogy Papers: University of Nebraska State Museum, University of Nebraska State Museum 1999 PHYLOGENETIC SYSTEMATICS OF THE BOROPHAGINAE (CARNIVORA: CANIDAE) Xiaoming Wang Richard H. Tedford Beryl E. Taylor Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museummammalogy This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Museum, University of Nebraska State at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mammalogy Papers: University of Nebraska State Museum by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. PHYLOGENETIC SYSTEMATICS OF THE BOROPHAGINAE (CARNIVORA: CANIDAE) XIAOMING WANG Research Associate, Division of Paleontology American Museum of Natural History and Department of Biology, Long Island University, C. W. Post Campus, 720 Northern Blvd., Brookville, New York 11548 -1300 RICHARD H. TEDFORD Curator, Division of Paleontology American Museum of Natural History BERYL E. TAYLOR Curator Emeritus, Division of Paleontology American Museum of Natural History BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY Number 243, 391 pages, 147 figures, 2 tables, 3 appendices Issued November 17, 1999 Price: $32.00 a copy Copyright O American Museum of Natural History 1999 ISSN 0003-0090 AMNH BULLETIN Monday Oct 04 02:19 PM 1999 amnb 99111 Mp 2 Allen Press • DTPro System File # 01acc (large individual, composite figure, based Epicyon haydeni ´n. (small individual, based on AMNH 8305) and Epicyon saevus Reconstruction of on specimens from JackNorth Swayze America. Quarry). Illustration These by two Mauricio species Anto co-occur extensively during the late Clarendonian and early Hemphillian of western 2 1999 WANG ET AL.: SYSTEMATICS OF BOROPHAGINAE 3 CONTENTS Abstract .................................................................... -

Bayesian Phylogenetic Estimation of Fossil Ages Rstb.Royalsocietypublishing.Org Alexei J

Downloaded from http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on June 20, 2016 Bayesian phylogenetic estimation of fossil ages rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org Alexei J. Drummond1,2 and Tanja Stadler2,3 1Department of Computer Science, University of Auckland, Auckland 1010, New Zealand 2Department of Biosystems Science and Engineering, Eidgeno¨ssische Technische Hochschule Zu¨rich, 4058 Basel, Switzerland Research 3Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (SIB), Lausanne, Switzerland Cite this article: Drummond AJ, Stadler T. Recent advances have allowed for both morphological fossil evidence 2016 Bayesian phylogenetic estimation of and molecular sequences to be integrated into a single combined inference fossil ages. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 371: of divergence dates under the rule of Bayesian probability. In particular, 20150129. the fossilized birth–death tree prior and the Lewis-Mk model of discrete morphological evolution allow for the estimation of both divergence times http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0129 and phylogenetic relationships between fossil and extant taxa. We exploit this statistical framework to investigate the internal consistency of these Accepted: 3 May 2016 models by producing phylogenetic estimates of the age of each fossil in turn, within two rich and well-characterized datasets of fossil and extant species (penguins and canids). We find that the estimation accuracy of One contribution of 15 to a discussion meeting fossil ages is generally high with credible intervals seldom excluding the issue ‘Dating species divergences using rocks true age and median relative error in the two datasets of 5.7% and 13.2%, and clocks’. respectively. The median relative standard error (RSD) was 9.2% and 7.2%, respectively, suggesting good precision, although with some outliers. -

Genus/Species Skull Ht Lt Wt Stage Range Abacinonyx See Acinonyx Abathomodon See Speothos A

Genus/Species Skull Ht Lt Wt Stage Range Abacinonyx see Acinonyx Abathomodon see Speothos A. fossilis see Icticyon pacivorus? Pleistocene Brazil Abelia U.Miocene Europe Absonodaphoenus see Pseudarctos L.Miocene USA A. bathygenus see Cynelos caroniavorus Acarictis L.Eocene W USA cf. A. ryani Wasatchian Colorado(US) A. ryani Wasatchian Wyoming, Colorado(US) Acinomyx see Acinonyx Acinonyx M.Pliocene-Recent Europe,Asia,Africa,N America A. aicha 2.3 m U.Pliocene Morocco A. brachygnathus Pliocene India A. expectata see Miracinonyx expectatus? Or Felis expectata? A. intermedius M.Pleistocene A. jubatus living Cheetah M.Pliocene-Recent Algeria,Europe,India,China A. pardinensis 91 cm 3 m 60 kg Astian-Biharian Italy,India,China,Germany,France A. sp. L.Pleistocene Tanzania,Ethiopia A. sp. Cf. Inexpectatus Blancan-Irvingtonian California(US) A. studeri see Miracinonyx studeri Blancan Texas(US) A. trumani see Miracinonyx trumani Rancholabrean Wyoming,Nevada(US) Acionyx possibly Acinonyx? A. cf. Crassidens Hadar(Ethiopia) Acrophoca 1.5 m U.Miocene-L.Pliocene Peru,Chile A. longirostris U.Miocene-L.Pliocene Peru A. sp. U.Miocene-L.Pliocene Chile Actiocyon M-U.Miocene W USA A. leardi Clarendonian California(US) A. sp. M.Miocene Oregon(US) Adcrocuta 82 cm 1.5 m U.Miocene Europe,Asia A. advena A. eximia 80 cm 1.5 m Vallesian-Turolian Europe(widespread),Asia(widespread) Adelphailurus U.Miocene-L.Pliocene W USA, Mexico,Europe A. kansensis Hemphillian Arizona,Kansas(US),Chihuahua(Mexico) Adelpharctos M.Oligocene Europe Adilophontes L.Miocene W USA A. brachykolos Arikareean Wyoming(US) Adracodon probably Adracon Eocene France A. quercyi probably Adracon quercyi Eocene France Adracon U.Eocene-L.Oligocene France A. -

1: Beast2.1.3 R1

1: Beast2.1.3_r1 0.93 Canis adustus 0.89 Canis mesomelas 0.37 Canis simensis Canis arnensis 1 Lycaon pictus 1 Cuon javanicus 0.57 Xenocyon texanus 0.91 Canis antonii 0.96 0.35 Canis falconeri 1 Canis dirus 1 Canis armbrusteri 0.060.27 Canis lupus Canis chihliensis Canis etruscus 0.98 0.99 0.26 Canis variabilis 0.11 Canis edwardii 0.93 Canis mosbachensis 0.68 0.58 Canis latrans Canis aureus 0.94 Canis palmidens 0.94 Canis lepophagus 1 0.41 Canis thooides Canis ferox 0.99 Eucyon davisi 0.8 Cerdocyon texanus Vulpes stenognathus Leptocyon matthewi 0.98 Urocyon cinereoargenteus 0.85 Urocyon minicephalus 0.96 1 Urocyon citronus 1 Urocyon galushi 0.96 Urocyon webbi 1 1 Metalopex merriami 0.23 Metalopex macconnelli 0.68 Leptocyon vafer 1 Leptocyon leidyi Leptocyon vulpinus 0.7 Leptocyon gregorii 1 Leptocyon douglassi Leptocyon mollis 0.32 Borophagus dudleyi 1 Borophagus hilli 0.98 Borophagus diversidens 0.97 Borophagus secundus 0.18 Borophagus parvus 1 Borophagus pugnator 1 Borophagus orc 1 Borophagus littoralis 0.96 Epicyon haydeni 1 0.92 Epicyon saevus Epicyon aelurodontoides Protepicyon raki 0.98 0.28 Carpocyon limosus 0.96 Carpocyon webbi 0.97 0.98 Carpocyon robustus Carpocyon compressus 0.17 0.87 Paratomarctus euthos Paratomarctus temerarius Tomarctus brevirostris 0.31 0.85 0.35 Tomarctus hippophaga 0.17 Tephrocyon rurestris Protomarctus opatus 0.24 0.58 Microtomarctus conferta Metatomarctus canavus Psalidocyon marianae 0.79 1 Aelurodon taxoides 0.32 0.27 Aelurodon ferox 1 Aelurodon stirtoni 0.14 Aelurodon mcgrewi 0.33 Aelurodon asthenostylus -

Agate Fossil Beds National Monument Geologic Resources Inventory Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Agate Fossil Beds National Monument Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2009/080 THIS PAGE: Fossil diorama at Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, an omnivorous entelodont (Daeodon or Dinohyus) stands over a chalicothere (Moropus), Agate Fossil Beds NM. ON THE COVER: University Hill on the left and Carnegie Hill on the right, site of the main fossil excavations, Agate Fossil Beds NM. NPS Photos. Agate Fossil Beds National Monument Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2009/080 Geologic Resources Division Natural Resource Program Center P.O. Box 25287 Denver, Colorado 80225 March 2009 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Denver, Colorado The Natural Resource Publication series addresses natural resource topics that are of interest and applicability to a broad readership in the National Park Service and to others in the management of natural resources, including the scientific community, the public, and the NPS conservation and environmental constituencies. Manuscripts are peer-reviewed to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and is designed and published in a professional manner. Natural Resource Reports are the designated medium for disseminating high priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. Examples of the diverse array of reports published in this series include vital signs monitoring plans; "how to" resource management papers; proceedings of resource management workshops or conferences; annual reports of resource programs or divisions of the Natural Resource Program Center; resource action plans; fact sheets; and regularly-published newsletters. -

File # 01Acc (Large Individual, Composite figure, Based Epicyon Haydeni «N

AMNH BULLETIN Monday Oct 04 02:19 PM 1999 amnb 99111 Mp 2 Allen Press • DTPro System File # 01acc (large individual, composite figure, based Epicyon haydeni ´n. (small individual, based on AMNH 8305) and Epicyon saevus Reconstruction of on specimens from JackNorth Swayze America. Quarry). Illustration These by two Mauricio species Anto co-occur extensively during the late Clarendonian and early Hemphillian of western 2 1999 WANG ET AL.: SYSTEMATICS OF BOROPHAGINAE 3 CONTENTS Abstract ..................................................................... 9 Introduction .................................................................. 10 Institutional Abbreviations ................................................... 11 Acknowledgments .......................................................... 12 History of Study .............................................................. 13 Materials and Methods ........................................................ 18 Scope ...................................................................... 18 Species Determination ........................................................ 18 Taxonomic Nomenclature ..................................................... 19 Format ..................................................................... 19 Chronological Framework .................................................... 20 Definitions .................................................................. 21 Systematic Paleontology ....................................................... 21 Subfamily Borophaginae Simpson, -

Paleoecology of Fossil Species of Canids (Canidae, Carnivora, Mammalia)

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH BOHEMIA, FACULTY OF SCIENCES Paleoecology of fossil species of canids (Canidae, Carnivora, Mammalia) Master thesis Bc. Isabela Ok řinová Supervisor: RNDr. V ěra Pavelková, Ph.D. Consultant: prof. RNDr. Jan Zrzavý, CSc. České Bud ějovice 2013 Ok řinová, I., 2013: Paleoecology of fossil species of canids (Carnivora, Mammalia). Master thesis, in English, 53 p., Faculty of Sciences, University of South Bohemia, České Bud ějovice, Czech Republic. Annotation: There were reconstructed phylogeny of recent and fossil species of subfamily Caninae in this study. Resulting phylogeny was used for examining possible causes of cooperative behaviour in Caninae. The study tried tu explain evolution of social behavior in canids. Declaration: I hereby declare that I have worked on my master thesis independently and used only the sources listed in the bibliography. I hereby declare that, in accordance with Article 47b of Act No. 111/1998 in the valid wording, I agree with the publication of my master thesis in electronic form in publicly accessible part of the STAG database operated by the University of South Bohemia accessible through its web pages. Further, I agree to the electronic publication of the comments of my supervisor and thesis opponents and the record of the proceedings and results of the thesis defence in accordance with aforementioned Act No. 111/1998. I also agree to the comparison of the text of my thesis with the Theses.cz thesis database operated by the National Registry of University Theses and a plagiarism detection system. In České Bud ějovice, 13. December 2013 Bc. Isabela Ok řinová Acknowledgements: First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor Věra Pavelková for her great support, patience and many valuable comments and advice. -

MAMMALIAN SPECIES NO. 222, Pp. I-A, 4 Ñgs

MAMMALIAN SPECIES NO. 222, pp. i-a, 4 ñgs. AilurUS fulgenS. By MUes S. Roberts and John L. Gittleman Published 14 November 1984 by The American Society of Mammalogists Ailurus F. Cuvier, 1825 darker in color than those from western areas (Pocock, 1921; Thomas, 1902). Ailurus F. Cuvier 1825:3. Type species Ailurus futgens by mono- typy. DISTRIBUTION. The red panda is found between 2,200 Arctaelurus Gloger 1841:28. Renaming of Ailurus F. Cuvier 1825. and 4,800 m in temperate forests of the Himalayas and high moun- tains of northern Burma and western Sichuan and Yunnan (Fig. 4). CONTEXT AND CONTENT. Order Carnivora, Superfam- The distribution is associated closely with temperate forests having ily Canoidea, Family Ailuridae (placed by some in Procyonidae; see bamboo-thicket understories (Allen 1938; Anon., 1978; Feng et al., REMARKS). The genus Ailurus includes only one species. Classi- 1981; Jackson, 1978; Mierow and Shrestha, 1978; Roberts, 1982a; fication below the subordinal level follows Pocock (1941). Sowerby, 1932; Stainton, 1972). The confirmed western-most range of Ailurus seems to be the Ailurus fulgens F. Cuvier, 1825 Namlung Valley in Mugu District and the Lake Rara region of northwestern Nepal (Jackson, 1978). The southern limit is the Lia- Red Panda kiang Range of western Yunnan and the northern and eastern limit is the upper Min Valley of western Sichuan. The existence of Ailu- Ailurus fiilgens F. Cuvier 1825. Type locality designated as "East rus in southwestern Tibet and northern Arunachal Pradesh is strong- Indies." ly suspected but has not been documented. A specimen exhibited Ailurus ochraceus Hodgson 1847:1118. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Carnivory

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Carnivory in the Oligo-Miocene: Resource Specialization, Competition, and Coexistence Among North American Fossil Canids A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Biology by Mairin Francesca Aragones Balisi 2018 © Copyright by Mairin Francesca Aragones Balisi 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Carnivory in the Oligo-Miocene: Resource Specialization, Competition, and Coexistence Among North American Fossil Canids by Mairin Francesca Aragones Balisi Doctor of Philosophy in Biology University of California, Los Angeles 2018 Professor Blaire Van Valkenburgh, Chair Competition likely shaped the evolution of the mammalian family Canidae (dogs and their ancestors; order Carnivora). From their origin 40 million years ago (Ma), early canids lived alongside potential competitors that may have monopolized the large-carnivore niche—such as bears, bear-dogs, and nimravid saber-toothed cats—before becoming large and hypercarnivorous (diet of >70% meat) later in their history. This ecomorphological context, along with high phylogenetic resolution and an outstanding fossil record, makes North American fossil canids an ideal system for investigating how biotic interactions (e.g. competition) and ecological specialization (e.g. hypercarnivory) might influence clade evolution. Chapter 1 investigates whether ecological generalization enables species to have longer durations and broader geographic range. I developed and applied a carnivory index to 100+ ii species, processing 3708 occurrences through a new duration-estimation method accounting for varying fossil preservation. A non-linear relationship between duration and carnivory emerged: both hyper- and hypocarnivores have shorter durations than mesocarnivores. Chapter 2 tests the cost of hypercarnivory, quantified as elevated extinction risk. -

Journal of Paleontology

Journal of Paleontology http://journals.cambridge.org/JPA Additional services for Journal of Paleontology: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here A Borophagine canid (Carnivora: Canidae: Borophaginae) from the middle Miocene Chesapeake Group of eastern North America Steven E. Jasinski and Steven C. Wallace Journal of Paleontology / Volume 89 / Issue 06 / November 2015, pp 1082 - 1088 DOI: 10.1017/jpa.2016.17, Published online: 09 May 2016 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0022336016000172 How to cite this article: Steven E. Jasinski and Steven C. Wallace (2015). A Borophagine canid (Carnivora: Canidae: Borophaginae) from the middle Miocene Chesapeake Group of eastern North America. Journal of Paleontology, 89, pp 1082-1088 doi:10.1017/jpa.2016.17 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/JPA, IP address: 206.224.29.126 on 11 May 2016 Journal of Paleontology, 89(6), 2015, p. 1082–1088 Copyright © 2016, The Paleontological Society 0022-3360/16/0088-0906 doi: 10.1017/jpa.2016.17 A Borophagine canid (Carnivora: Canidae: Borophaginae) from the middle Miocene Chesapeake Group of eastern North America Steven E. Jasinski,1,2,3 and Steven C. Wallace3,4 1Paleontology and Geology Section, State Museum of Pennsylvania, 300 North Street, Harrisburg, PA 17120, U.S.A. 〈[email protected]〉 2Department of Earth and Environmental Science, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA 3Don Sundquist Center of Excellence in Paleontology, Johnson City, TN 37614, USA 4Department of Geosciences, East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, TN 37614, USA 〈[email protected]〉 Abstract.—A tooth recovered from the middle Miocene Choptank Formation (Chesapeake Group) of Maryland is identified as a new cynarctin borophagine (Canidae: Borophaginae: Cynarctina), here called Cynarctus wangi n. -

HAWK RIM: a GEOLOGIC and PALEONTOLOGICAL DESCRIPTION of a NEW BARSTOVIAN LOCALITY in CENTRAL OREGON by WIN NADIA FRANCIS MCLAUGH

HAWK RIM: A GEOLOGIC AND PALEONTOLOGICAL DESCRIPTION OF A NEW BARSTOVIAN LOCALITY IN CENTRAL OREGON by WIN NADIA FRANCIS MCLAUGHLIN A THESIS Presented to the Department of Geological Science and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science September 2012 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Win Nadia Francis McLaughlin Title: Hawk Rim: A Geologic and Paleontological Description of a New Barstovian Locality in Central Oregon This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science degree in the Department of Geological Science by: Samantha Hopkins Chair Ray Weldon Member Steve Frost Outside Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation/Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2012 ii © 2012 WIN NADIA FRANCIS MCLAUGHLIN iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Win Nadia Francis McLaughlin Master of Science Department of Geological Science September 2012 Title: Hawk Rim: A Geologic and Paleontological Description of a New Barstovian Locality in Central Oregon Hawk Rim represents a new mid-Miocene site in Eastern Oregon. This time period offers a rare chance to observe dramatic climatic changes, such as sudden warming trends. The site is sedimentologically and stratigraphically consistent with the Mascall Formation of the John Day Basin to the north and east of Hawk Rim. Hawk Rim preserves taxa such as canids Cynarctoides acridens and Paratomarctus temerarius, the felid Pseudaelurus skinneri, castorids Anchitheriomys and Monosaulax, tortoises and the remains of both cormorants and owls.