Alice in Wonderland Glossary of Terms for Madge Miller’S Adaptation from Lewis Carroll

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll With 42 Illustrations by John Tenniel All in the golden afternoon Full leisurely we glide ; For both our oars, with little skill, By little arms are plied, While little hands make vain pretence Our wanderings to guide. Ah, cruel Three ! In such an hour, Beneath such dreamy weather, To beg a tale of breath too weak To stir the tiniest feather ! Yet what can one poor voice avail Against three tongues together ? Imperious Prima flashes forth Her edict “ to begin it” : In gentler tones Secunda hopes “ There will be nonsense in it ! ” While Tertia interrupts the tale Not more than once a minute. Anon, to sudden silence won, In fancy they pursue The dream-child moving through a land Of wonders wild and new, In friendly chat with bird or beast— And half believe it true. And ever, as the story drained The wells of fancy dry, And faintly strove that weary one To put the subject by, “ The rest next time—” “ It is next time ! ” The happy voices cry. Thus grew the tale of Wonderland : Thus slowly, one by one, Its quaint events were hammered out— And now the tale is done, And home we steer, a merry crew, Beneath the setting sun. Alice ! A childish story take, And, with a gentle hand, Lay it where Childhood’s dreams are twined In Memory’s mystic band, Like pilgrim’s wither’d wreath of flowers Pluck’d in a far-off land. CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I Down the Rabbit-Hole 7 II The Pool of Tears 14 III A Caucus-Race and a Long Tale 22 IV The Rabbit Sends in a Little Bill 29 V Advice from a Caterpillar 38 VI Pig -

Lewis Carroll at Play •}'Y It, -Pjf55 Dhhl )')~, I

CQS€.; RS 3b Lewis Carroll at Play •}'Y It, -PJf55 dhhl )')~, I A Thesis Presented to the Chancellor's Scholars Council of The University ofNorth Carolina at Pembroke In Partial Fulfillment Ofthe Requirements for Completion of The Chancellor's Scholars Program By James Nichols December 4,2001 Faculty Advisor's Approval ~ Faculty Advisor's Approvaldi: Faculty Advisor's APproi :£ Date ~ 296640 Lewis Carroll at Play Chancellor's Scholars Paper Outline I. Introduction A. Popularity ofthe Alice books B. Lewis Carroll background & summary ofAlice books C. Lewis Carroll put Alice books together for insight D. Lewis Carroll incorporated math, logic and games in Through the Looking Glass and Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, which benefits computer scientists and mathematicians. II. Mathematics in Alice books relates to computer science A. Properties 1. Identity 2. Inverses 3. No solution problems (nonsense) 4. Rules not absolute-always an exception B. Symmetry C. Dimensions D. Meaning ofmathematical phrases E. Null class F. Math puzzles 1. Multiplying 2. Alice's running 3. Line puzzle 4. Time 5. Zero-sum game 6. Transformations G. Mathematical puns m. Logic in the Alice books relates to computer science A. Concepts being broken down B. Humpty Dumpty chooses what words mean C. Need for Order D. Alice as a logician E. Logic ofa child F. Don't assume anything G. Symbols N. Games in the Alice books relates to computer science A. Cards B. Chess C. Acrostics D. Doublets E. Syzgies F. Magic Tricks 1. Fan 2. Apple 3. Magic Number G. Mazes H. Carroll's Games V. What Lewis Carroll offers to Computer Science and Mathematics today A. -

Open Maryallenfinal Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH SIX IMPOSSIBLE THINGS BEFORE BREAKFAST: THE LIFE AND MIND OF LEWIS CARROLL IN THE AGE OF ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND MARY ALLEN SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in English with honors in English Reviewed and approved* by the following: Kate Rosenberg Assistant Teaching Professor of English Thesis Supervisor Christopher Reed Distinguished Professor of English, Visual Culture, and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Honors Adviser * Electronic approvals are on file. i ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes and offers connections between esteemed children’s literature author Lewis Carroll and the quality of mental state in which he was perceived by the public. Due to the imaginative nature of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, it has been commonplace among scholars, students, readers, and most individuals familiar with the novel to wonder about the motive behind the unique perspective, or if the motive was ever intentional. This thesis explores the intentionality, or lack thereof, of the motives behind the novel along with elements of a close reading of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. It additionally explores the origins of the concept of childhood along with the qualifications in relation to time period, culture, location, and age. It identifies common stereotypes and presumptions within the subject of mental illness. It aims to achieve a connection between the contents of Carroll’s novel with -

Alice in Wonderland: Chapter Seven: a Mad Tea Party

ALICE IN WONDERLAND: CHAPTER SEVEN: A MAD TEA PARTY CHAPTER VII A Mad Tea-Party There was a table set out under a tree in front of the house, and the March Hare and the Hatter were having tea at it: a Dormouse was sitting between them, fast asleep, and the other two were using it as a cushion, resting their elbows on it, and talking over its head. `Very uncomfortable for the Dormouse,' thought Alice; `only, as it's asleep, I suppose it doesn't mind.' The table was a large one, but the three were all crowded together at one corner of it: `No room! No room!' they cried out when they saw Alice coming. `There's plenty of room!' said Alice indignantly, and she sat down in a large arm-chair at one end of the table. Mad Tea Party `Have some wine,' the March Hare said in an encouraging tone. Alice looked all round the table, but there was nothing on it but tea. `I don't see any wine,' she remarked. `There isn't any,' said the March Hare. `Then it wasn't very civil of you to offer it,' said Alice angrily. `It wasn't very civil of you to sit down without being invited,' said the March Hare. `I didn't know it was your table,' said Alice; `it's laid for a great many more than three.' 1 ALICE IN WONDERLAND: CHAPTER SEVEN: A MAD TEA PARTY `Your hair wants cutting,' said the Hatter. He had been looking at Alice for some time with great curiosity, and this was his first speech. -

Lewis Carroll: Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND by Lewis Carroll with fourty-two illustrations by John Tenniel This book is in public domain. No rigths reserved. Free for copy and distribution. This PDF book is designed and published by PDFREEBOOKS.ORG Contents Poem. All in the golden afternoon ...................................... 3 I Down the Rabbit-Hole .......................................... 4 II The Pool of Tears ............................................... 9 III A Caucus-Race and a Long Tale .................................. 14 IV The Rabbit Sends in a Little Bill ................................. 19 V Advice from a Caterpillar ........................................ 25 VI Pig and Pepper ................................................. 32 VII A Mad Tea-Party ............................................... 39 VIII The Queen’s Croquet-Ground .................................... 46 IX The Mock Turtle’s Story ......................................... 53 X The Lobster Quadrille ........................................... 59 XI Who Stole the Tarts? ............................................ 65 XII Alice’s Evidence ................................................ 70 1 Poem All in the golden afternoon Of wonders wild and new, Full leisurely we glide; In friendly chat with bird or beast – For both our oars, with little skill, And half believe it true. By little arms are plied, And ever, as the story drained While little hands make vain pretence The wells of fancy dry, Our wanderings to guide. And faintly strove that weary one Ah, cruel Three! In such an hour, To put the subject by, Beneath such dreamy weather, “The rest next time –” “It is next time!” To beg a tale of breath too weak The happy voices cry. To stir the tiniest feather! Thus grew the tale of Wonderland: Yet what can one poor voice avail Thus slowly, one by one, Against three tongues together? Its quaint events were hammered out – Imperious Prima flashes forth And now the tale is done, Her edict ‘to begin it’ – And home we steer, a merry crew, In gentler tone Secunda hopes Beneath the setting sun. -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games ( Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack ( Arcade, TG16) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1943: Kai (TG16) 12. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 13. 1944: The Loop Master ( Arcade) 14. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 15. 19XX: The War Against Destiny ( Arcade) 16. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge ( Arcade) 17. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 18. 2020 Super Baseball ( Arcade, SNES) 19. 21-Emon (TG16) 20. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 21. 3 Count Bout ( Arcade) 22. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 23. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 24. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 25. 3-D WorldRunner (NES) 26. 3D Asteroids (Atari 7800) 27. -

Cast List- Alice in Wonderland Alice- Rachel M. Mathilda- Chynna A

Cast List- Alice in Wonderland Alice- Rachel M. Mathilda- Chynna A. Cheshire Cat 1- Jelayshia B. Cheshire Cat 2- Skylar B. Cheshire Cat 3- Shikirah H. White Rabbit- Cassie C. Doorknob- Mackenzie L. Dodo Bird- Latasia C. Rock Lobsters & Sea Creatures- Kayla M., Mariscia M., Bar’Shon B., Brandon E., Camryn M., Tyler B., Maniya T., Kaitlyn G., Destiney R., Sole’ H., Deja M. Tweedle Dee- Kayleigh F. Tweedle Dum- Tynigie R. Rose- Kristina M. Petunia- Cindy M. Lily- Katie B. Violet- Briana J. Daisy- Da’Johnna F. Flower Chorus- Keonia J., Shalaya F., Tricity R. and named flowers Caterpillar- Alex M. Mad Hatter- Andrew L. March Hare- Glenn F. Royal Cardsmen- ALL 3 Diamonds- Shemar H. 4 Spades- Aaron M. Ace Spades- Kevin T. 5 Diamonds- Abraham S. 2 Clubs- Ben S. Queen of Hearts- Alyceanna W. King of Hearts- Ethan G. Ensemble/Chorus- Katie B. Kevin T. Ben S. Briana J. Kristina M. Latasia C. Da’Johnna F. Shalaya F. Shamara H. Shemar H. Cindy M. Keonia J. Tricity R. Kaitlyn G. Sole’ H. Aaron M. Deja M. Destiney R. Abraham S. Chanyce S. Kayla M. Camryn M. Destiney A. Tyler B. Mariscia M. Brandon E. Bar’Shon B. Bridgette B. Maniya T. Amari L. Dodgsonland—ALL I’m Late—4th Very Good Advice—4th Grade Ocean of Tears—Dodo, Rock Lobsters, Sea Creatures (select 3rd and 4th) I’m Late-Reprise—4th How D’ye Do and Shakes Hands—Tweedles and Alice The Golden Afternoon—5th Grade girls Zip-a-dee-do-dah—4th and 5th The Unbirthday Song—5th Grade Painting the Roses Red—ALL Simon Says—Queen, Alice (ALL cardsmen) The Unbirthday Song-Reprise—Mad Hatter, Queen, King, 5th Grade Who Are You?—Tweedles, Flowers, Alice, Mad Hatter, White Rabbit, Queen & Named Cardsmen Alice in Wonderland: Finale—ALL Zip-a-dee-doo-dah: Bows—ALL . -

ALICE's ADVENTURES in WONDERLAND Lewis Carroll

The Jefferson Performing Arts Society Presents 1118 Clearview Parkway Metairie, LA 70001 504-885-2000 www.jpas.org 1 | P a g e Table of Contents Teacher’s Notes………………………..…………..…………..……..3 Standards and Benchmarks…………………..……………….…..5 Background………………………………………..…….………………6 Alice’s Adventures, Comparing and Contrasting ………… 12 Art, Math and Set Design: Alice in Minecraft Land...................................................33 The Science of Color Meets the White Rabbit and the March Hare...................74 Additional Resources…………………………………..…..….….106 2 | P a g e Teacher’s Notes Music and Lyrics by Sammy Fain and Bob Hilliard, Oliver Wallace and Cy Coban, Allie Wrubel and Ray Gilbert, Mack David, Al Hoffman and Jerry Livingston Music Adapted and Arranged and Additional Music and Lyrics by Bryan Louiselle Book Adapted and Additional Lyrics by David Simpatico Based on the 1951 Disney film, Alice in Wonderland, and the Lewis Carroll novels, "The Adventures of Alice in Wonderland" and "Through the Looking Glass," Lewis Carroll's famous heroine comes to life in this delightful adaptation of the classic Disney film. Lewis Carroll was the nom de plume of Charles L. Dodgson. Born on January 27, 1832 in Daresbury, Cheshire, England, Charles Dodgson wrote and created games as a child. At age 20 he received a studentship at Christ Church and was appointed a lecturer in mathematics. Dodgson was shy but enjoyed creating stories for children. Within the academic discipline of mathematics, Dodgson worked primarily in the fields of geometry, linear and matrix algebra, mathematical logic, and recreational mathematics, producing nearly a dozen books under his real name. Dodgson also developed new ideas in linear algebra (e.g., the first printed proof of the Kronecker-Capelli theorem,) probability, and the study of elections (e.g., Dodgson's method); some of this work was not published until well after his death. -

Alice in Wonderland (3)

Alice in Wonderland (3) Overview of chapters 7-12 Chapter 7: A Mad Tea Party Alice tries to take tea with the Hatter, the March Hare, and a Dormouse. She takes part in a confusing conversation and hears the beginning of the Dormouse’s tale. Madness: the Hatter and the Hare The Mad Hatter and the March Hare are another example of how in Wonderland language creates reality (rather than just reflecting it) “as mad as a hatter” (also because Victorian hatters worked with mercury, and mercury poisoning leads to insanity) Madness: the Hatter and the Hare “as mad as a March (>marsh?) hare” Tenniel drew the March Hare with wisps of straws on its head. This was a clear symbol of lunacy or insanity in the Victorian age. Unsurprisingly, Disney’s Hare does not retain any trace of the straws. A Mad Tea Party: a central chapter Alice reaches the furthest point in her descent into chaos: the word ‘mad’ is particularly prominent. The conversation at the tea table is absurd and aggressive, a parody perhaps of Victorian hypocrite ‘civil’ conversations during snobbish tea-parties. Alice’s puzzlement: the conversation “seemed to her to have no sort of meaning, and yet it was certainly English”. Agon at the tea table “Have some wine,” the March Hare said in an encouraging tone. [...] “I don’t see any wine,” she remarked. “There isn’t any,” said the March Hare. “Then it wasn’t very civil of you to offer it,” said Alice angrily. “It wasn’t very civil of you to sit down without being invited,” said the March Hare. -

Audition Pack

AUDITION PACK Production details Our production of Alice in Wonderland will take place at Millers Theatre, Seefeldstrasse 225, 8008 Zürich. Production dates Saturday 2nd March 2019 at 2.30pm and 6.30pm Sunday 3rd March 2019 at 2.30pm and 6.30pm Want to audition? If you are aged between 8 and 18 you can book your audition time by signing up at www.simplytheatre.com/productions/audition Audition details Auditions for Alice in Wonderland will take place on the 8th and 9th December 2018 at Gymnos Studios, Gladbachstr. 119, 8044 Zürich. If you are selected for a CALLBACK, you will need to be available on the afternoon of Sunday 9th December. If you want to audition but cannot make these dates please let us know in advance and we may be able to help. Audition times are: Saturday 8th December Sunday 9th December Session 1: 14.45 – 15.45 Session 4: 11.00 – 12.00 Session 2: 15.55 – 16.55 Session 3: 17.00 – 18.00 Recall auditions: 13.00 – 16.00 (by invite only) Please indicate which audition slot you would like when booking your time. 1 What will I be doing in the audition process? As part of your audition, you will be asked to perform a small monologue. These monologues are listed at the end of this pack. This monologue should be memorised. When learning your monologue, remember to consider where you think your character is at the time of this monologue, who (s)he may be talking to, and what they are feeling. How can you get this information over to your audience (audition panel) through your audition? You may feel free to choose any of the monologues for your audition, as no matter what you perform at audition you will still be considered for all parts. -

Alice in Wonderland

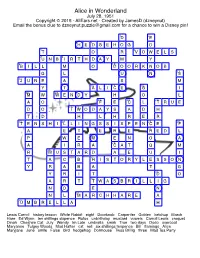

Alice in Wonderland July 28, 1951 Copyright © 2015 - AllEars.net - Created by JamesD (dzneynut) Email the bonus clue to [email protected] for a chance to win a Disney pin! 1 2 D E 3 4 H E D G E H O G D 5 6 T O R V O W E L S 7 8 U N B I R T H D A Y M Y 9 10 B I L L M O D O O R K N O B 11 G L U N S 12 J U N E A S M 13 14 15 Y T A L I C E G I 16 17 M W W E N D Y H O L 18 19 20 A O F E C L T R U E 21 22 D O T W O D A Y S A D H T D H L H R E R 23 24 25 26 T E N S H I L L I N G S S I X P E N C E F 27 A E T E R E R E D L 28 P W E M E N O A 29 A I R A C A T Q M 30 R M U S T A R D A E U I 31 T A C B H I S T O R Y L E S S O N Y R A B A T G 32 Y R I T D O 33 A R T T W A S B R I L L I G N O E N 34 N L M A R C H H A R E A 35 U M B R E L L A H Lewis Carroll history lesson White Rabbit eight Doorknob Carpenter Golden ketchup March Hare Ed Wynn ten shillings sixpence Rufus unbirthday mustard vowels Carroll Lewis croquet Dinah Cheshire Cat July Wendy Im Late umbrella smirk True two days Dodo overcoat Maryanne Tulgey Woods Mad Hatter cat red six shillings tenpence Bill flamingo Alice Maryjane June smile False bird hedgehog Dormouse Twas Brillig three Mad Tea Party ★ Thurl Ravenscroft, a member of the singing group, the Mellomen, who sing #27 Across, appears to have lost his head while singing a familiar song in what popular theme park attraction? (2 words) [HAUNTEDMANSION] Across Down 3. -

KNIGHT LETTER D De E the Lewis Carroll Society of North America

d de e KNIGHT LETTER d de e The Lewis Carroll Society of North America Fall 2017 Volume II Issue 29 Number 99 d de e CONTENTS d de e The Rectory Umbrella Of Books and Things g g Delaware and Dodgson, Contemporary Review of or, Wonderlands: Egad! Ado! 1 Nabokov’s Anya Discovered 36 chris morgan victor fet Drawing the Looking-Glass Country 11 The Albanian Gheg Wonderland 36 dmitry yermolovich byron sewell Is snark Part of a Cyrillic Doublet? 16 Alice and the Graceful White Rabbit 37 victor fet & michael everson robert stek USC Libraries’ 13th Wonderland Award 18 Alice’s Adventures in Punch 38 linda cassady andrew ogus A “New” Lewis Carroll Puzzle 19 Alice’s Adventures under clare imholtz the Land of Enchantment 39 Two Laments: One for Logic cindy watter & One for the King 20 Alice D. 40 august a. imholtz, jr cindy watter Mad Hatters and March Hares 41 mischmasch rose owens g AW, ill. Charles Santore 41 andrew ogus Leaves from the Deanery Garden— Serendipity—Sic, Sic, Sic 21 Rare, Uncollected, & Unpublished Verse of Lewis Carroll 42 Ravings from the Writing Desk 25 edward wakeling stephanie lovett The Alice Books and the Contested All Must Have Prizes 26 Ground of the Natural World 42 matt crandall hayley rushing Arcane Illustrators: Goranka Vrus Murtić 29 Evergreen 43 mark burstein Nose Is a Nose Is a Nose 30 From Our Far-flung goetz kluge Correspondents g In Memoriam: Morton Cohen 32 Art & Illustration—Articles & Academia— edward guiliano Books—Events, Exhibits, & Places—Internet & Technology—Movies & Television—Music— Carrollian Notes Performing Arts—Things 44 g More on Morton 34 Alice in Puzzleland: The Jabberwocky Puzzle Project 34 chris morgan d e Drawing the Looking-Glass Country dmitry yermolovich d e llustrators do not often explain why they have Messerschmidt, famous for his “character heads,” drawn their pictures the way they did.