Lewis Carroll: Author, Mathematician, and Christian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lewis Carroll at Play •}'Y It, -Pjf55 Dhhl )')~, I

CQS€.; RS 3b Lewis Carroll at Play •}'Y It, -PJf55 dhhl )')~, I A Thesis Presented to the Chancellor's Scholars Council of The University ofNorth Carolina at Pembroke In Partial Fulfillment Ofthe Requirements for Completion of The Chancellor's Scholars Program By James Nichols December 4,2001 Faculty Advisor's Approval ~ Faculty Advisor's Approvaldi: Faculty Advisor's APproi :£ Date ~ 296640 Lewis Carroll at Play Chancellor's Scholars Paper Outline I. Introduction A. Popularity ofthe Alice books B. Lewis Carroll background & summary ofAlice books C. Lewis Carroll put Alice books together for insight D. Lewis Carroll incorporated math, logic and games in Through the Looking Glass and Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, which benefits computer scientists and mathematicians. II. Mathematics in Alice books relates to computer science A. Properties 1. Identity 2. Inverses 3. No solution problems (nonsense) 4. Rules not absolute-always an exception B. Symmetry C. Dimensions D. Meaning ofmathematical phrases E. Null class F. Math puzzles 1. Multiplying 2. Alice's running 3. Line puzzle 4. Time 5. Zero-sum game 6. Transformations G. Mathematical puns m. Logic in the Alice books relates to computer science A. Concepts being broken down B. Humpty Dumpty chooses what words mean C. Need for Order D. Alice as a logician E. Logic ofa child F. Don't assume anything G. Symbols N. Games in the Alice books relates to computer science A. Cards B. Chess C. Acrostics D. Doublets E. Syzgies F. Magic Tricks 1. Fan 2. Apple 3. Magic Number G. Mazes H. Carroll's Games V. What Lewis Carroll offers to Computer Science and Mathematics today A. -

Unpublished Letters by George Macdonald

Defining Death as “More Life”: Unpublished Letters by George MacDonald Glenn Edward Sadler Who lives, he dies; who dies, he is alive. Phantastes ch. XIII ost readers of George MacDonald’s fiction, especially of his faerieM romances and fairytales, will recall his penetrating treatment of the subject of death and dying. A classic passage occurs, for example, at the conclusion of The Golden Key, when the Old Man of the Sea finally asks Mossy the ultimate question: [end of page 4] “You have tasted death now,” said the Old Man. “Is it good?” “It is good,” said Mossy. “It is better than life.” “No,” said the Old Man: “it is only more life.”1 Equally moving, in spite of its sentimentality, is the ending of At the Back of the North Wind, which depicts graphically Diamond’s dream-in- sleep death. Similarly, there is the ethereal death of the king, who becomes a sacrifice of “flaming red roses,” viewed by Curdie, at the end ofThe Princess and Curdie. As a writer of parables and fairytales, George MacDonald is at his best when he is seeing death through the eyes of a child. Through the eyes of his fictional children—Mossy, Diamond and Curdie—MacDonald envisions his cardinal belief in the cosmic role of the child, who as a redemptive figure participates in and exemplifies universal love and immortality. Mossy and Tangle become agents of life-giving renewal. Diamond is a source of lasting love. And Curdie is a symbol of universal victory over evil. In each case it is the process of dying-into-life (“more life”) that is MacDonald’s major concern: it is a theme which is to be found in everything he wrote. -

North Wind: a Journal of George Macdonald Studies

North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies Volume 39 Article 6 1-1-2020 A Personal Reflection on Colin Manlove and Stephen Prickett John Pennington Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/northwind Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Pennington, John (2020) "A Personal Reflection on Colin Manlove and Stephen Prickett," North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies: Vol. 39 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/northwind/vol39/iss1/6 This In Memoriam is brought to you for free and open access by the English at Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Personal Reflection on Colin Manlove and Stephen Prickett John Pennington At the end of George MacDonald’s At the Back of the North Wind, the narrator enters Diamond’s bedroom and sees the young boy seemingly asleep on his bed. The narrator states: “I saw at once how it was . I knew that he had gone to the back of the north wind” (298). With utter certitude, I’m sure that Colin and Stephen are also at the back of the north wind. My career as an academic in literature is indebted to Colin and Stephen, for they paved the way for serious academic study of George MacDonald, hardly a household name outside of the devoted readers of fantasy, fairy tales, and theology when I started my PhD program in the mid- 1980’s. -

Good Morning!»: Una Broma Filológica En the Hobbit

«Good Morning!»: una broma filológica en The Hobbit 1. Un hobbit bien educado El señor Bilbo Baggins, Esq., es un hobbit bien educado. La primera vez que lo escuchamos está ofreciendo un «Good Morning!» a un anciano tocado con un pintoresco sombrero en la soleada mañana en que este se plantó ante su puerta (H, i, 5-7). Nada menos se podía esperar del hijo de los señores Bungo Baggins y Belladona Took, un hobbit respetable, vástago de una familia respetable. Con razón comenzó a inquietarse al escuchar la palabra «adventure» salir de los labios del ahora inoportuno visitante. Con exquisito tacto intentó despedirlo utilizando la misma expresión de la bienvenida. Impertinente, el anciano desveló su nombre, Gandalf, e insistió en su propósito. Gracias a la providencia, al final, nuestro asustado hobbit pudo regresar a la seguridad de su hogar sin mayor daño. Desde el comienzo, The Hobbit está impregnado con ese tono cómico del que el autor, J. R. R. Tolkien, va a renegar con posterioridad. El estudio del humor en esta obra es un camino fecundo: permite saborear parte de los ingredientes que el Profesor introdujo en el caldero. Unos ingredientes quizás menos nobles y elevados que otros bien conocidos. Fijar la mirada en el pequeño fragmento de la conversación inicial es perfecto para mostrar los mecanismos que Tolkien utiliza. Un lectura demorada del mismo muestra que la formación filológica del autor es esencial para desentrañar las referencias implícitas. Por ejemplo, las constantes alusiones al significado de las expresiones utilizadas nos dirigen, a nuestro entender, hacia las teorías lingüísticas del inkling Owen Barfield (1898 – 1997). -

Cweb Study Guide

" " " " " Alice in Wonderland " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " STUDY " GUIDE " " Designed and developed" " " by: Lexi Barnett" " : Meet the Author Lewis Carrol Lewis Carroll was the pseudonym of Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a lecturer in mathematics at Christ Church, Oxford, who lived from 1832 to 1898. Carroll’s physical deformities, partial deafness, and irrepressible stammer made him an unlikely candidate for producing one of the most popular and enduring children’s fantasies in the English language. Carroll’s unusual appearance caused him to behave awkwardly around other adults, and his students at Oxford saw him as a stuffy and boring teacher. Underneath Carroll’s awkward exterior, however, lay a brilliant and imaginative artist. Carroll’s keen grasp of mathematics and logic inspired the linguistic humor and witty wordplay in his stories. Additionally, his unique understanding of children’s minds allowed him to compose imaginative fiction that appealed to young people. In 1856, Carroll and met the Liddell family. During their frequent afternoon boat trips on the river, Carroll told the Liddells fanciful tales. Alice quickly became Carroll’s favorite of the three girls, and he made her the subject of the stories that would later became Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. Almost ten years after first meeting the Liddells, Carroll compiled the stories and .1 submitted the completed manuscript for publication. pg If you lived all by yourself,Translating what would your housethe lookJabberwocky! like? Draw your ideal house below: There are many poems recited in Alice in Wonderland- one of the most bizarre is the Jabberwocky! What do you think it means? Write your translation of the words to the right of the poem " ’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe: All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe. -

ALICE's ADVENTURES in WONDERLAND Lewis Carroll

The Jefferson Performing Arts Society Presents 1118 Clearview Parkway Metairie, LA 70001 504-885-2000 www.jpas.org 1 | P a g e Table of Contents Teacher’s Notes………………………..…………..…………..……..3 Standards and Benchmarks…………………..……………….…..5 Background………………………………………..…….………………6 Alice’s Adventures, Comparing and Contrasting ………… 12 Art, Math and Set Design: Alice in Minecraft Land...................................................33 The Science of Color Meets the White Rabbit and the March Hare...................74 Additional Resources…………………………………..…..….….106 2 | P a g e Teacher’s Notes Music and Lyrics by Sammy Fain and Bob Hilliard, Oliver Wallace and Cy Coban, Allie Wrubel and Ray Gilbert, Mack David, Al Hoffman and Jerry Livingston Music Adapted and Arranged and Additional Music and Lyrics by Bryan Louiselle Book Adapted and Additional Lyrics by David Simpatico Based on the 1951 Disney film, Alice in Wonderland, and the Lewis Carroll novels, "The Adventures of Alice in Wonderland" and "Through the Looking Glass," Lewis Carroll's famous heroine comes to life in this delightful adaptation of the classic Disney film. Lewis Carroll was the nom de plume of Charles L. Dodgson. Born on January 27, 1832 in Daresbury, Cheshire, England, Charles Dodgson wrote and created games as a child. At age 20 he received a studentship at Christ Church and was appointed a lecturer in mathematics. Dodgson was shy but enjoyed creating stories for children. Within the academic discipline of mathematics, Dodgson worked primarily in the fields of geometry, linear and matrix algebra, mathematical logic, and recreational mathematics, producing nearly a dozen books under his real name. Dodgson also developed new ideas in linear algebra (e.g., the first printed proof of the Kronecker-Capelli theorem,) probability, and the study of elections (e.g., Dodgson's method); some of this work was not published until well after his death. -

Alice in Wonderland

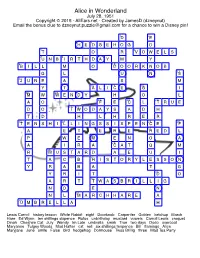

Alice in Wonderland July 28, 1951 Copyright © 2015 - AllEars.net - Created by JamesD (dzneynut) Email the bonus clue to [email protected] for a chance to win a Disney pin! 1 2 D E 3 4 H E D G E H O G D 5 6 T O R V O W E L S 7 8 U N B I R T H D A Y M Y 9 10 B I L L M O D O O R K N O B 11 G L U N S 12 J U N E A S M 13 14 15 Y T A L I C E G I 16 17 M W W E N D Y H O L 18 19 20 A O F E C L T R U E 21 22 D O T W O D A Y S A D H T D H L H R E R 23 24 25 26 T E N S H I L L I N G S S I X P E N C E F 27 A E T E R E R E D L 28 P W E M E N O A 29 A I R A C A T Q M 30 R M U S T A R D A E U I 31 T A C B H I S T O R Y L E S S O N Y R A B A T G 32 Y R I T D O 33 A R T T W A S B R I L L I G N O E N 34 N L M A R C H H A R E A 35 U M B R E L L A H Lewis Carroll history lesson White Rabbit eight Doorknob Carpenter Golden ketchup March Hare Ed Wynn ten shillings sixpence Rufus unbirthday mustard vowels Carroll Lewis croquet Dinah Cheshire Cat July Wendy Im Late umbrella smirk True two days Dodo overcoat Maryanne Tulgey Woods Mad Hatter cat red six shillings tenpence Bill flamingo Alice Maryjane June smile False bird hedgehog Dormouse Twas Brillig three Mad Tea Party ★ Thurl Ravenscroft, a member of the singing group, the Mellomen, who sing #27 Across, appears to have lost his head while singing a familiar song in what popular theme park attraction? (2 words) [HAUNTEDMANSION] Across Down 3. -

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland Alice in Wonderland (Movie) (Book) Similarities ______

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland Chapter 12 ~ Page 1 © Gay Miller ~ Created by Gay Miller CHAPTER XII. Alice's Evidence 'Here!' cried Alice, quite forgetting in the flurry of the moment how large she had grown in the last few minutes, and she jumped up in such a hurry that she tipped over the jury-box with the edge of her skirt, upsetting all the jurymen on to the heads of the crowd below, and there they lay sprawling about, reminding her very much of a globe of goldfish she had accidentally upset the week before. 'Oh, I beg your pardon!' she exclaimed in a tone of great dismay, and began picking them up again as quickly as she could, for the accident of the goldfish kept running in her head, and she had a vague sort of idea that they must be collected at once and put back into the jury-box, or they would die. 'The trial cannot proceed,' said the King in a very grave voice, 'until all the jurymen are back in their proper places—all,' he repeated with great emphasis, looking hard at Alice as he said do. Alice looked at the jury-box, and saw that, in her haste, she had put the Lizard in head downwards, and the poor little thing was waving its tail about in a melancholy way, being quite unable to move. She soon got it out again, and put it right; 'not that it signifies much,' she said to herself; 'I should think it would be quite as much use in the trial one way up as the other.' As soon as the jury had a little recovered from the shock of being upset, and their slates and pencils had been found and handed back to them, they set to work very diligently to write out a history of the accident, all except the Lizard, who seemed too much overcome to do anything but sit with its mouth open, gazing up into the roof of the court. -

Annihilating Nihilistic Nonsense Tim Burton Guts Lewis Carroll’S Jabberwocky

Annihilating Nihilistic Nonsense Tim Burton Guts Lewis Carroll’s Jabberwocky Alice in Wonderland seems to beg for a morbid interpretation. Whether it's Marilyn Manson's "Eat Me, Drink Me," the video game "American McGee's Alice," or Svankmajer's "Alice" and "Jabberwocky," artists love bringing out the darker elements of Alice’s adventures as she wanders among creepy creatures. The 2010 Tim Burton film is the latest twisted adaptation, featuring an older Alice that slays the Jabberwocky. However, unlike the other adaptations, Burton’s adaptation draws most of its grim outlook by gutting Alice in Wonderland of its fundamental core - its nonsense. Alice in Wonderland uses nonsense to liberate, offering frightening amounts of freedom through its playful use of nonsense. However, Burton turns this whimsy into menacing machinations - he pretends to use nonsense for its original liberating purpose but actually uses it for adult plots and preset paths. Burton takes the destructive power of Alice’s insistence for order and amplifies it dramatically, completely removing its original subversive release from societal constraints. Under the façade of paying tribute to Carroll’s whimsical nonsense verse, Burton directly removes nonsense’s anarchic freedom and replaces it with a destructive commitment to sense. This brutal change to both plot and structure turns Alice into a mindless juggernaut, slaying not only the Jabberwock, but also the realm of nonsense, non-linear narrative and real world empires. At first, nonsense in Lewis Carroll’s books seems to just a light-hearted play with language. Even before we come into Wonderland, the idea of nonsense as just a simple child’s diversion is given by the epigraph. -

Lewis Carroll, George Macdonald and Charles Dickens

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository FANTASTICAL REFLECTIONS: LEWIS CARROLL, GEORGE MACDONALD AND CHARLES DICKENS By HAYLEY HANNAH FLYNN A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis examines the presence and importance of the fantastical in literature of the Victorian period, a time most frequently associated with rationality. A variety of cultural sources, including popular entertainment, optical technology and the fairy tale, show the extent of the impact the fantastical has on the period and provides further insight into its origins. Lewis Carroll, George MacDonald and Charles Dickens, who each present very different style of writing, provide similar insight into the impact of the fantastical on literature of the period. By examining the similarities and influences that exist between these three authors and other cultural sources of the fantastical a clear pattern can be seen, demonstrating the origins and use of the fantastical in Victorian literature and providing a new stance from which it should be viewed. -

The Female Rebel in Pan's Labyrinth, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass

GOTHIC AGENTS OF REVOLT: THE FEMALE REBEL IN PAN'S LABYRINTH, ALICE'S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND AND THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS Michail-Chrysovalantis Markodimitrakis A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2016 Committee: Piya-Pal Lapinski, Advisor Kimberly Coates © 2016 Michail-Chrysovalantis Markodimitrakis All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Piya Pal-Lapinski, Advisor The Gothic has become a mode of transforming reality according to the writers’ and the audiences’ imagination through the reproduction of hellish landscapes and nightmarish characters and occurrences. It has also been used though to address concerns and criticize authoritarian and power relations between citizens and the State. Lewis Carroll’sAlice’s Adventures in Wonderland and its sequel Through the Looking Glass are stories written during the second part of the 19th century and use distinct Gothic elements to comment on the political situation in England as well as the power of language from a child’s perspective. Guillermo Del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth on the other hand uses Gothic horror and escapism to demonstrate the monstrosities of fascism and underline the importance of revolt and resistance against State oppression. This thesis will be primarily concerned with Alice and Ophelia as Gothic protagonists that become agents of revolt against their respective states of oppression through the lens of Giorgio Agamben and Hannah Arendt. I will examine how language and escapism are used as tools by the literary creators to depict resistance against the Law and societal pressure; I also aim to demonstratehow the young protagonists themselves refuse to comply with the authoritarian methods used against them byadult the representatives of Power. -

Objects of Nonsense, Anarchy, and Order: Romantic Theology in Lewis Carroll’S and George Macdonald’S Nonsense Literature Adam Walker

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St. Norbert College North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies Volume 37 Article 2 1-1-2018 Objects of Nonsense, Anarchy, and Order: Romantic Theology in Lewis Carroll’s and George MacDonald’s Nonsense Literature Adam Walker Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/northwind Recommended Citation Walker, Adam (2018) "Objects of Nonsense, Anarchy, and Order: Romantic Theology in Lewis Carroll’s and George MacDonald’s Nonsense Literature," North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies: Vol. 37 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/northwind/vol37/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Objects of Nonsense, Anarchy, and Order: Romantic Theology in Lewis Carroll's and George MacDonald's Nonsense Literature Adam Walker Introduction “Nonsense criticism, as it currently exists,” writes Josephine Gabelman in her new book A Theology of Nonsense (2016), “is essentially a secular enterprise. It is philosophical and psychoanalytical, philological and mathematical; it may be studied from a historical or cultural perspective, but apparently not a religious one” (162). Past scholarship has, in fact, not only avoided a serious consideration of theology regarding nonsense literature, but some scholars have gone so far as to insist that nonsense literature lacks any sense of the religious at all.