Through the Looking-Glass: Translating Nonsense

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Return of the Jabber W Ock Graham / Neale

THE RETURN OF THE JABBERWOCK THE RETURN OF A brave little boy sets off on an adventure to find the Jabberwock, just like his great grandfather before him. But what creatures will he encounter in mysterious Tulgey Wood? Illustrated by David Neale Written by Oakley Graham GRAHAM / NEALE RRP £5.99 For more Top That! books visit our website: Published by Top That! Publishing plc www.topthatpublishing.com Tide Mill Way, Woodbridge, Suffolk, IP12 1AP, UK Copyright © 2013 Top That! Publishing plc All rights reserved 0 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 Printed and bound in China XXX-XXX-XX-XXXX-XX Published by Top That! Publishing plc Tide Mill Way, Woodbridge, Suffolk, IP12 1AP, UK www.topthatpublishing.com Copyright © 2013 Top That! Publishing plc All rights reserved 0 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 Printed and bound in China Creative Director – Simon Couchman Editorial Director – Daniel Graham Illustrated by David Neale Written by Oakley Graham All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Neither this book nor any part or any of the illustrations, photographs or reproductions contained in it shall be sold or disposed of otherwise than as a complete book, and any unauthorised sale of such part illustration, photograph or reproduction shall be deemed to be a breach of the publisher’s copyright. ISBN 978-1-78244-171-7 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Printed and bound in China Written by Oakley Graham Illustrated by David Neale For the magnificent seven; Jazz, Amber, Noah, Oakie, Jemima, Isis & Isadora. -

THE LAND BEYOND the MAGIC MIRROR by E

GREYHAWK CASTLE DUNGEON MODULE EX2 THE LAND BEYOND THE MAGIC MIRROR by E. Gary Gygax AN ADVENTURE IN A WONDROUS PLACE FOR CHARACTER LEVELS 9-12 No matter the skill and experience of your party, they will find themselves dazed and challenged when they pass into The Land Beyond the Magic Mirror! Distributed to the book trade in the United States by Random House, Inc. and in Canada by Random House of Canada Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. Distributed in the United Kingdom by TSR Hobbies (UK) Ltd. AD&D and WORLD OF GREYHAWK are registered trademarks owned by TSR Hobbies, Inc. ©1983 TSR Hobbies, Inc. All Rights Reserved. TSR Hobbies, Inc. TSR Hobbies (UK) Ltd. POB 756 The Mill, Rathmore Road Lake Geneva, Cambridge CB14AD United Kingdom Printed in U.S.A. WI 53147 ISBN O 88038-025-X 9073 TABLE OF CONTENTS This module is the companion to Dungeonland and was originally part of the Greyhawk Castle dungeon complex. lt is designed so that it can be added to Dungeonland, used alone, or made part of virtually any campaign. It has an “EX” DUNGEON MASTERS PREFACE ...................... 2 designation to indicate that it is an extension of a regular THE LAND BEYOND THE MAGIC MIRROR ............. 4 dungeon level—in the case of this module, a far-removed .................... extension where all adventuring takes place on another plane The Magic Mirror House First Floor 4 of existence that is quite unusual, even for a typical AD&D™ The Cellar ......................................... 6 Second Floor ...................................... 7 universe. This particular scenario has been a consistent ......................................... -

Cweb Study Guide

" " " " " Alice in Wonderland " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " STUDY " GUIDE " " Designed and developed" " " by: Lexi Barnett" " : Meet the Author Lewis Carrol Lewis Carroll was the pseudonym of Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a lecturer in mathematics at Christ Church, Oxford, who lived from 1832 to 1898. Carroll’s physical deformities, partial deafness, and irrepressible stammer made him an unlikely candidate for producing one of the most popular and enduring children’s fantasies in the English language. Carroll’s unusual appearance caused him to behave awkwardly around other adults, and his students at Oxford saw him as a stuffy and boring teacher. Underneath Carroll’s awkward exterior, however, lay a brilliant and imaginative artist. Carroll’s keen grasp of mathematics and logic inspired the linguistic humor and witty wordplay in his stories. Additionally, his unique understanding of children’s minds allowed him to compose imaginative fiction that appealed to young people. In 1856, Carroll and met the Liddell family. During their frequent afternoon boat trips on the river, Carroll told the Liddells fanciful tales. Alice quickly became Carroll’s favorite of the three girls, and he made her the subject of the stories that would later became Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. Almost ten years after first meeting the Liddells, Carroll compiled the stories and .1 submitted the completed manuscript for publication. pg If you lived all by yourself,Translating what would your housethe lookJabberwocky! like? Draw your ideal house below: There are many poems recited in Alice in Wonderland- one of the most bizarre is the Jabberwocky! What do you think it means? Write your translation of the words to the right of the poem " ’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe: All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe. -

ALICE's ADVENTURES in WONDERLAND Lewis Carroll

The Jefferson Performing Arts Society Presents 1118 Clearview Parkway Metairie, LA 70001 504-885-2000 www.jpas.org 1 | P a g e Table of Contents Teacher’s Notes………………………..…………..…………..……..3 Standards and Benchmarks…………………..……………….…..5 Background………………………………………..…….………………6 Alice’s Adventures, Comparing and Contrasting ………… 12 Art, Math and Set Design: Alice in Minecraft Land...................................................33 The Science of Color Meets the White Rabbit and the March Hare...................74 Additional Resources…………………………………..…..….….106 2 | P a g e Teacher’s Notes Music and Lyrics by Sammy Fain and Bob Hilliard, Oliver Wallace and Cy Coban, Allie Wrubel and Ray Gilbert, Mack David, Al Hoffman and Jerry Livingston Music Adapted and Arranged and Additional Music and Lyrics by Bryan Louiselle Book Adapted and Additional Lyrics by David Simpatico Based on the 1951 Disney film, Alice in Wonderland, and the Lewis Carroll novels, "The Adventures of Alice in Wonderland" and "Through the Looking Glass," Lewis Carroll's famous heroine comes to life in this delightful adaptation of the classic Disney film. Lewis Carroll was the nom de plume of Charles L. Dodgson. Born on January 27, 1832 in Daresbury, Cheshire, England, Charles Dodgson wrote and created games as a child. At age 20 he received a studentship at Christ Church and was appointed a lecturer in mathematics. Dodgson was shy but enjoyed creating stories for children. Within the academic discipline of mathematics, Dodgson worked primarily in the fields of geometry, linear and matrix algebra, mathematical logic, and recreational mathematics, producing nearly a dozen books under his real name. Dodgson also developed new ideas in linear algebra (e.g., the first printed proof of the Kronecker-Capelli theorem,) probability, and the study of elections (e.g., Dodgson's method); some of this work was not published until well after his death. -

Audition Pack

AUDITION PACK Production details Our production of Alice in Wonderland will take place at Millers Theatre, Seefeldstrasse 225, 8008 Zürich. Production dates Saturday 2nd March 2019 at 2.30pm and 6.30pm Sunday 3rd March 2019 at 2.30pm and 6.30pm Want to audition? If you are aged between 8 and 18 you can book your audition time by signing up at www.simplytheatre.com/productions/audition Audition details Auditions for Alice in Wonderland will take place on the 8th and 9th December 2018 at Gymnos Studios, Gladbachstr. 119, 8044 Zürich. If you are selected for a CALLBACK, you will need to be available on the afternoon of Sunday 9th December. If you want to audition but cannot make these dates please let us know in advance and we may be able to help. Audition times are: Saturday 8th December Sunday 9th December Session 1: 14.45 – 15.45 Session 4: 11.00 – 12.00 Session 2: 15.55 – 16.55 Session 3: 17.00 – 18.00 Recall auditions: 13.00 – 16.00 (by invite only) Please indicate which audition slot you would like when booking your time. 1 What will I be doing in the audition process? As part of your audition, you will be asked to perform a small monologue. These monologues are listed at the end of this pack. This monologue should be memorised. When learning your monologue, remember to consider where you think your character is at the time of this monologue, who (s)he may be talking to, and what they are feeling. How can you get this information over to your audience (audition panel) through your audition? You may feel free to choose any of the monologues for your audition, as no matter what you perform at audition you will still be considered for all parts. -

Lewis Carroll: Author, Mathematician, and Christian

Lewis Carroll: Author, Mathematician, and Christian David L. Neuhouser Mathematics Department Taylor University Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832-1898), better known as Lewis Carroll, is best known as the creative and imaginative author of the Alice stories, but he was also a mathematician at Christ Church College, Oxford University and a devout Christian. His mathematics, especially mathematical logic, contributed much to the charming “nonsense” in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. However, his Christian thought is not evident in those books. In fact, they contain many parodies of morality poems for children. As a result of reading just these books, one might conclude that he was not even interested in morality. But to those who knew him personally, he seemed to be a rather pious, stodgy person. Also, he wrote essays and letters in defense of morality and Christianity as well as books and articles on mathematics. His writings on morality showed little of his literary imagination and his writings on mathematics give no indication of his Christianity. Only in Sylvie and Bruno and Sylvie and Bruno Concluded did Dodgson attempt to bring his literary creativity, mathematics, and Christianity all together in one artistic creation. This paper will attempt to answer the following questions. What motivated him to make this attempt and how successful was it? The Alice stories were the first really successful children’s stories which did not have obvious moral teachings. They were just for fun. However he wrote articles and letters against “indecent literature,” joking about sacred things, and immorality in plays. Some projects that he planned but never completed were: selections from the Bible to be memorized, selections from the Bible with pictures for children, and selections from Shakespeare with inappropriate content for young girls deleted. -

Alice Through the Looking-Glass Is Presented by Special Arrangement with the Estate of James Crerar Reaney

This production was originally produced at the Stratford Festival in association with Canada’s National Arts Centre in 2014. nov dec 26 19 2015 THEATRE FOR YOUNG AUDIENCES GENEROUSLY SUPPORTED BY STUDY GUIDE Adapted from the Stratford Festival 2014 Study Guide by Luisa Appolloni This production was originally produced at the Stratford Festival in association with Canada's National Arts Centre in 2014. Alice Through the Looking-Glass is presented by special arrangement with the Estate of James Crerar Reaney. 1 THEATRE ETIQUETTE “The theater is so endlessly fascinating because it's so accidental. It's so much like life.” – Arthur Miller Arrive Early: Latecomers may not be admitted to a performance. Please ensure you arrive with enough time to find your seat before the performance starts. Cell Phones and Other Electronic Devices: Please TURN OFF your cell phones/iPods/gaming systems/cameras. We have seen an increase in texting, surfing, and gaming during performances, which is very distracting for the performers and other audience members. The use of cameras and recording devices is strictly prohibited. Talking During the Performance: You can be heard (even when whispering!) by the actors onstage and the audience around you. Disruptive patrons will be removed from the theatre. Please wait to share your thoughts and opinions with others until after the performance. Food/Drinks: Food and hot drinks are not allowed in the theatre. Where there is an intermission, concessions may be open for purchase of snacks and drinks. There is complimentary water in the lobby. Dress: There is no dress code at the Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre, but we respectfully reQuest that patrons refrain from wearing hats in the theatre. -

ARTICLE: Jan Susina: Playing Around in Lewis Carroll's Alice Books

Playing Around in Lewis Carroll’s Alice Books • Jan Susina Mathematician Charles Dodgson’s love of play and his need for rules came together in his use of popular games as part of the structure of the two famous children’s books, Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, he wrote under the pseudonym Lewis Carroll. The author of this article looks at the interplay between the playing of such games as croquet and cards and the characters and events of the novels and argues that, when reading Carroll (who took a playful approach even in his academic texts), it is helpful to understand games and game play. Charles Dodgson, more widely known by his pseudonym Lewis Carroll, is perhaps one of the more playful authors of children’s literature. In his career, as a children’s author and as an academic logician and mathematician, and in his personal life, Carroll was obsessed with games and with various forms of play. While some readers are surprised by the seemingly split personality of Charles Dodgson, the serious mathematician, and Lewis Carroll, the imaginative author of children’s books, it was his love of play and games and his need to establish rules and guidelines that effectively govern play that unite these two seemingly disparate facets of Carroll’s personality. Carroll’s two best-known children’s books—Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking- Glass and What Alice Found There (1871)—use popular games as part of their structure. In Victoria through the Looking-Glass, Florence Becker Lennon has gone so far as to suggest about Carroll that “his life was a game, even his logic, his mathematics, and his singular ordering of his household and other affairs. -

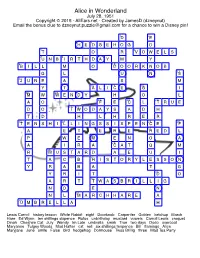

Alice in Wonderland

Alice in Wonderland July 28, 1951 Copyright © 2015 - AllEars.net - Created by JamesD (dzneynut) Email the bonus clue to [email protected] for a chance to win a Disney pin! 1 2 D E 3 4 H E D G E H O G D 5 6 T O R V O W E L S 7 8 U N B I R T H D A Y M Y 9 10 B I L L M O D O O R K N O B 11 G L U N S 12 J U N E A S M 13 14 15 Y T A L I C E G I 16 17 M W W E N D Y H O L 18 19 20 A O F E C L T R U E 21 22 D O T W O D A Y S A D H T D H L H R E R 23 24 25 26 T E N S H I L L I N G S S I X P E N C E F 27 A E T E R E R E D L 28 P W E M E N O A 29 A I R A C A T Q M 30 R M U S T A R D A E U I 31 T A C B H I S T O R Y L E S S O N Y R A B A T G 32 Y R I T D O 33 A R T T W A S B R I L L I G N O E N 34 N L M A R C H H A R E A 35 U M B R E L L A H Lewis Carroll history lesson White Rabbit eight Doorknob Carpenter Golden ketchup March Hare Ed Wynn ten shillings sixpence Rufus unbirthday mustard vowels Carroll Lewis croquet Dinah Cheshire Cat July Wendy Im Late umbrella smirk True two days Dodo overcoat Maryanne Tulgey Woods Mad Hatter cat red six shillings tenpence Bill flamingo Alice Maryjane June smile False bird hedgehog Dormouse Twas Brillig three Mad Tea Party ★ Thurl Ravenscroft, a member of the singing group, the Mellomen, who sing #27 Across, appears to have lost his head while singing a familiar song in what popular theme park attraction? (2 words) [HAUNTEDMANSION] Across Down 3. -

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland Alice in Wonderland (Movie) (Book) Similarities ______

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland Chapter 12 ~ Page 1 © Gay Miller ~ Created by Gay Miller CHAPTER XII. Alice's Evidence 'Here!' cried Alice, quite forgetting in the flurry of the moment how large she had grown in the last few minutes, and she jumped up in such a hurry that she tipped over the jury-box with the edge of her skirt, upsetting all the jurymen on to the heads of the crowd below, and there they lay sprawling about, reminding her very much of a globe of goldfish she had accidentally upset the week before. 'Oh, I beg your pardon!' she exclaimed in a tone of great dismay, and began picking them up again as quickly as she could, for the accident of the goldfish kept running in her head, and she had a vague sort of idea that they must be collected at once and put back into the jury-box, or they would die. 'The trial cannot proceed,' said the King in a very grave voice, 'until all the jurymen are back in their proper places—all,' he repeated with great emphasis, looking hard at Alice as he said do. Alice looked at the jury-box, and saw that, in her haste, she had put the Lizard in head downwards, and the poor little thing was waving its tail about in a melancholy way, being quite unable to move. She soon got it out again, and put it right; 'not that it signifies much,' she said to herself; 'I should think it would be quite as much use in the trial one way up as the other.' As soon as the jury had a little recovered from the shock of being upset, and their slates and pencils had been found and handed back to them, they set to work very diligently to write out a history of the accident, all except the Lizard, who seemed too much overcome to do anything but sit with its mouth open, gazing up into the roof of the court. -

Annihilating Nihilistic Nonsense Tim Burton Guts Lewis Carroll’S Jabberwocky

Annihilating Nihilistic Nonsense Tim Burton Guts Lewis Carroll’s Jabberwocky Alice in Wonderland seems to beg for a morbid interpretation. Whether it's Marilyn Manson's "Eat Me, Drink Me," the video game "American McGee's Alice," or Svankmajer's "Alice" and "Jabberwocky," artists love bringing out the darker elements of Alice’s adventures as she wanders among creepy creatures. The 2010 Tim Burton film is the latest twisted adaptation, featuring an older Alice that slays the Jabberwocky. However, unlike the other adaptations, Burton’s adaptation draws most of its grim outlook by gutting Alice in Wonderland of its fundamental core - its nonsense. Alice in Wonderland uses nonsense to liberate, offering frightening amounts of freedom through its playful use of nonsense. However, Burton turns this whimsy into menacing machinations - he pretends to use nonsense for its original liberating purpose but actually uses it for adult plots and preset paths. Burton takes the destructive power of Alice’s insistence for order and amplifies it dramatically, completely removing its original subversive release from societal constraints. Under the façade of paying tribute to Carroll’s whimsical nonsense verse, Burton directly removes nonsense’s anarchic freedom and replaces it with a destructive commitment to sense. This brutal change to both plot and structure turns Alice into a mindless juggernaut, slaying not only the Jabberwock, but also the realm of nonsense, non-linear narrative and real world empires. At first, nonsense in Lewis Carroll’s books seems to just a light-hearted play with language. Even before we come into Wonderland, the idea of nonsense as just a simple child’s diversion is given by the epigraph. -

The Musical Misadventures of a Girl Named Alice Book by JAMES DEVITA Music and Lyrics by BILL FRANCOEUR Based on the Novel Through the Looking Glass by LEWIS CARROLL

The Musical Misadventures of a Girl Named Alice based on the novel Through the Looking Glass by Lewis Carroll Book by JAMES DEVITA Music and Lyrics by BILL FRANCOEUR © Copyright 2002, JAMES DeVITA PERFORMANCE LICENSE The amateur acting rights to this play are controlled exclusively by PIONEER DRAMA SERVICE, INC., P.O. Box 4267, Englewood, Colorado 80155, without whose permission no performance, reading or presentation of any kind may be given. On all programs and advertising this notice must appear: “Produced by special arrangement with Pioneer Drama Service, Inc., Englewood, Colorado.” COPYING OR REPRODUCING ALL OR ANY PART OF THIS BOOK IN ANY MANNER IS STRICTLY FORBIDDEN BY LAW. All other rights in this play, including those of professional production, radio broadcasting and motion picture rights, are controlled by Pioneer Drama Service, Inc., to whom all inquiries should be addressed. WONDERLAN D! The Musical Misadventures of a Girl Named Alice Book by JAMES DEVITA Music and Lyrics by BILL FRANCOEUR based on the novel Through the Looking Glass by LEWIS CARROLL CAST OF CHARACTERS ALICE .............................................. the same one that chased the rabbit down the hole TROUBADOUR* .............................. quite the singer MOTHER’S VOICE .......................... offstage RED KING ....................................... soporific monarch WHITE KING .................................... defender of the crown RED QUEEN .................................... vicious, nasty temper WHITE QUEEN ...............................