JR Dymond and His Environments, 1887-1932

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Les Numéros En Bleu Renvoient Aux Cartes

210 Index Les numéros en bleu renvoient aux cartes. I13th Street Winery 173 Banques 195 The Upper Deck 64 Tranzac Club 129 37 Metcalfe Street 153 Barbara Barrett Lane 124 Velvet Underground 118 299 Queen Street West 73 Bars et boîtes de nuit Woody’s 78 314 Wellesley Street East 153 beerbistro 85 Bellwoods Brewery 117 Baseball 198 397 Carlton Street 152 Bier Markt Esplanade 99 Basketball 198 398 Wellesley Street East 153 Birreria Volo 122 Bata Shoe Museum 133 Black Bull Tavern 85 Beaches Easter Parade 199 Black Eagle 78 Beaches International Jazz Bovine Sex Club 117 Festival 200 A Boxcar Social 157 Accessoires 146 Beach, The 158, 159 Brassaii 85 Beauté 115 Activités culturelles 206 Cabana Pool Bar 60 Aéroports Canoe 85 Bellevue Square Park 106 A Billy Bishop Toronto City Castro’s Lounge 161 Berczy Park 96 Airport 189 C’est What? 99 Bickford Park 119 Toronto Pearson Clinton’s Tavern 129 Bière 196 International Airport 188 Crews 78 Aga Khan Museum 168 Bijoux 99, 144 Crocodile Rock 86 Billy Bishop Toronto City INDEX Alexandra Gates 133 dBar 146 Airport 189 Algonquin Island 62 Drake Hotel Lounge 117 Bird Kingdom 176 Alimentation 59, 84, 98, 108, El Convento Rico 122 Black Bull Tavern 74 115, 144, 155, 161 Elephant & Castle 86 Allan Gardens Free Times Cafe 122 Black Creek Pioneer Village 169 Conservatory 150 Hemingway’s 146 Alliance française de Lee’s Palace 129 Bloor Street 139, 141 Toronto 204 Library Bar 86 Blue Jays 198 Annesley Hall 136 Madison Avenue Pub 129 Bluffer’s Park 164 Annex, The 123, 125 Melody Bar 117 Brigantine Room 60 Antiquités 84, 98 Mill Street Brew Pub 99 Brock’s Monument 174 N’Awlins Jazz Bar & Grill 86 Architecture 47 Brookfield Place 70 Orbit Room 122 Argent 195 Brunswick House 124 Pauper’s Pub 129 Argus Corp. -

Fam Altout Last YORK 200 ~Tyojtk

~~ ----.~ ~ciIudiq Fam altout lAST YORK 200 ~tyOJtk TODMORDENMILLS IIlust. courtesy of Todmorden Mills Heritage Museum EAST YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY FASCINATING FACTS ABOUT EAST YORK It..T~ Fascinating Facts About East York is one of the Iiii r numerous events at the Library in celebrating IAIT TORK 200 "East York 200". The list is very selective and we apolo gize for any oversights. Our aim is to take you through out the Borough and back through time to encounter a compendium of unique people, places and things. S. Walter Stewart Branch Area 1. Why is East York celebrating 200 years in 1996? In July of 1796, two brothers, Isaiah and Aaron Skinner were given permission to build a grist mill in the Don Valley, which they proceeded to do that winter. This began an industrial complex of paper mill, grist mill, brewery and distillery with later additions. In 1996, East York is celebrating 200 years of community. The Eastwood and Skinner mill, ca. 1877 from Torofilo IIIl1Slraled POSI & Prcsetl/. Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library 2. What is the area of East York? East York covers a physical area of2,149.7 hectares (8.3 square miles). Of the six municipalities comprising the Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto, East York is the smallest in size, area-wise. 3. What are the symbols on the East York Coat of Arms and what do they signify? The British bulldog, from the Township of East York signifies the tenacity and courage of early settlers from Britain. The white rose of York is a symbol of peace from the settlers' homeland. -

LPRO E-Newsletter Feb 15 2021

E-Newsletter 15 February 2021 http://www.lyttonparkro.ca/ The Lytton Park Residents’ Organization (LPRO) is an incorporated non-profit association, representing member households from Lawrence Avenue West to Roselawn and Briar Hill Avenues, Yonge Street to Saguenay and Proudfoot Avenue. We care about protecting and advancing the community’s interests and fostering a sense of neighbourhood in our area. We work together to make our community stronger, sharing information about our community issues and events. “Together we do make a difference!” Keeping Our Community Connected: Follow us on Twitter! Our Twitter handle is @LyttonParkRO LPRO’s Community E-Newsletter - It’s FREE! If you do not already receive the LPRO’s E-Newsletter and would like to receive it directly, please register your email address at www.lyttonparkro.ca/newsletter-sign-up or send us an email to [email protected]. Please share this newsletter with neighbours! Check out LPRO’s New Website! Click HERE Community Residents’ Association Membership - Renew or Join for 2021 As a non-profit organization run by community volunteers, we rely on your membership to cover our costs to advocate for the community, provide newsletters, lead an annual community yard sale and a ravine clean-up, organize speaker events and host election candidate debates. Please join or renew your annual membership. The membership form and details on how to pay the $30 annual fee are on the last page of this newsletter or on our website at http://www.lyttonparkro.ca/ . If you are a Member you will automatically get LPRO’s Newsletters. Thank you for your support! Have a Happy Family Day! LPRO E-Newsletter – 15 February 2021 1 Settlement Achieved - 2908 Yonge Development at Chatsworth A lot has happened in a very short space of time, including a settlement which approves the zoning for a building at 2908 Yonge (the former Petrocan site at Chatsworth and Yonge). -

3D Map1103.Pdf

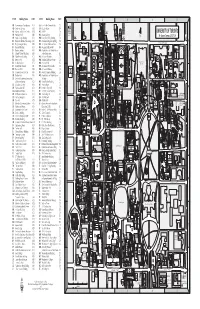

CODE Building Name GRID CODE Building Name GRID 1 2 3 4 5 AB Astronomy and Astrophysics (E5) LM Lash Miller Chemical Labs (D2) AD WR AD Enrolment Services (A2) LW Faculty of Law (B4) Institute of AH Alumni Hall, Muzzo Family (D5) M2 MARS 2 (F4) Child Study JH ST. GEORGE OI SK UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO 45 Walmer ROAD BEDFORD AN Annesley Hall (B4) MA Massey College (C2) Road BAY SPADINA ST. GEORGE N St. George Campus 2017-18 AP Anthropology Building (E2) MB Lassonde Mining Building (F3) ROAD SPADINA Tartu A A BA Bahen Ctr. for Info. Technology (E2) MC Mechanical Engineering Bldg (E3) BLOOR STREET WEST BC Birge-Carnegie Library (B4) ME 39 Queen's Park Cres. East (D4) BLOOR STREET WEST FE WO BF Bancroft Building (D1) MG Margaret Addison Hall (A4) CO MK BI Banting Institute (F4) MK Munk School of Global Affairs - Royal BL Claude T. Bissell Building (B2) at the Observatory (A2) VA Conservatory LI BN Clara Benson Building (C1) ML McLuhan Program (D5) WA of Music CS GO MG BR Brennan Hall (C5) MM Macdonald-Mowat House (D2) SULTAN STREET IR Royal Ontario BS St. Basil’s Church (C5) MO Morrison Hall (C2) SA Museum BT Isabel Bader Theatre (B4 MP McLennan Physical Labs (E2) VA K AN STREET S BW Burwash Hall (B4) MR McMurrich Building (E3) PAR FA IA MA K WW HO WASHINGTON AVENUE GE CA Campus Co-op Day Care (B1) MS Medical Sciences Building (E3) L . T . A T S CB Best Institute (F4) MU Munk School of Global Affairs - W EEN'S EEN'S GC CE Centre of Engineering Innovation at Trinity (C3) CHARLES STREET WEST QU & Entrepreneurship (E2) NB North Borden Building (E1) MUSEUM VP BC BT BW CG Canadiana Gallery (E3) NC New College (D1) S HURON STREET IS ’ B R B CH Convocation Hall (E3) NF Northrop Frye Hall (B4) IN E FH RJ H EJ SU P UB CM Student Commons (F2) NL C. -

Uot History Freidland.Pdf

Notes for The University of Toronto A History Martin L. Friedland UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London © University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2002 Toronto Buffalo London Printed in Canada ISBN 0-8020-8526-1 National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Friedland, M.L. (Martin Lawrence), 1932– Notes for The University of Toronto : a history ISBN 0-8020-8526-1 1. University of Toronto – History – Bibliography. I. Title. LE3.T52F75 2002 Suppl. 378.7139’541 C2002-900419-5 University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Humanities and Social Sciences Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the finacial support for its publishing activities of the Government of Canada, through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP). Contents CHAPTER 1 – 1826 – A CHARTER FOR KING’S COLLEGE ..... ............................................. 7 CHAPTER 2 – 1842 – LAYING THE CORNERSTONE ..... ..................................................... 13 CHAPTER 3 – 1849 – THE CREATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO AND TRINITY COLLEGE ............................................................................................... 19 CHAPTER 4 – 1850 – STARTING OVER ..... .......................................................................... -

78-90 Queen's Park

TE19.11.101 78-90 Queen’s Park UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO Centre for Civilization, Cultures and Cities Toronto and East York Community Council Meeting (TEYCC) - Agenda Item TE 19.2 | October 15th, 2020 Diller Scofidio + Renfro | architectsAlliance | ERA | Bousfields | NAK Design Strategies TORONTO AND EAST YORK COMMUNITY COUNCIL MEETING (TEYCC) - AGENDA ITEM TE 19.2 - OCTOBER 15TH, 2020 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. 16 total community consultation meetings held on this subject site by the University of Toronto over a 9 year period from 2011-2020. 2. Positive City Staff recommendation from Community Planning, Urban Design, Heritage Preservation Services. 3. Considerable height reduction from 81m in 2011 down to 42.25m now proposed. 4. Considerable Building Setback 36m from property line at Queen’s Park. 5. All applicable planning policy met, including view protection of Ontario Legislature. 6. Retention of heritage buildings on site with all major views to historic house (Falconer Hall) ensured. 7. Cultural Landscape of Queen’s Park and Philosopher’s Walk strongly considered, respected, and incorporated in the design by architects, landscape architect and heritage consultant. 8. All prominent old-growth trees retained. Some necessary tree removal to facilitate construction, but 31 new trees to be planted, ` well above tree replacement requirements. 9. Tree removal already reviewed closely and approved by City of Toronto Urban Forestry staff. 10. Approximately 3,380 sm of landscaped open space is proposed across the site (50% of the total site area). 11. No shadow impact to Philosopher’s Walk. Final version: Master Plan, 2011 Height: 81m TORONTO AND EAST YORK COMMUNITY COUNCIL MEETING (TEYCC) - AGENDA ITEM TE 19.2 - OCTOBER 15TH, 2020 3 EVOLUTION OF CCC SITE MASSING 2011 BUILDING HEIGHT = 81m MASTERPLAN + small forecourt Secondary Plan Masterplan CONSULTATION Workshops 1. -

Appendices, Bibliography & Index (Pp 473-530)

PL APPENDIX 1: ORDERS IN COUNCIL 473 P.C. 1988-58 eeting of the Committee of the llency the Governor General WHEREAS there exists a historic opportunity to create a unique, world class waterfront in Toronto: AWD WHEREAS there is a clear, public understanding that the challenge can only be achieved with more cooperation among the various levels of government, boards, commissions and special purpose bodies and the private sector: AND WHEREAS the Intergovernmental Waterfront Committee has identified a number of urgent matters that must be studied and dealt with: AND WHEREAS the Government of Canada has certain jurisdictional an6 property responsibilities in the area: Now therefore, the Committee of the Privy Council, on the recommendation of the Prime Minister, advise that the Honourable David Crombie be authorized to act as a Commissioner effective from June 1, 1988, and that a Commission, to be effective from that date, do issue under Part I of the Inquiries Act and under the Great Seal of Canada, appointing the Honourable David Crombie to be a Commissioner to inquire into and to. make recommendations regarding the future of the Toronto Waterfront and to seek the concurrence of affected authorities\ in such recommendations, in order to ensure that, in the public interest, Federal lands and jurisdiction serve to enhance the physical, environmental, legislative and administrative context governing the use, enjoyment and development of the Toronto Waterfront and related lands, and more particularly to examine (a) the role and mandate of the Toronto Harbour Commission: (b) the future of the Toronto Island Airport and related transportation services: (a) the ism protection and renewal nvironment insofar as they re esponsibilities and jur isd i . -

1320 CHR 92.4 02 Bonnell .Web. 607..636

JENNIFER BONNELL An Intimate Understanding of Place: Charles Sauriol and Toronto’s Don River Valley, 1927–1989 Abstract: Every summer from 1927 to 1968, Toronto conservationist Charles Sauriol and his family moved from their city home to a rustic cottage just a few kilometres away, within the urban wilderness of Toronto’s Don River Valley. In his years as a cottager, Sauriol saw the valley change from a picturesque setting of rural farms and woodlands to an increasingly threatened corridor of urban green space. His intimate familiarity with the valley led to a lifelong quest to protect it. This paper explores the history of conservation in the Don River Valley through Sauriol’s expe- riences. Changes in the approaches to protecting urban nature, I argue, are reflected in Sauriol’s personal experience – the strategies he employed, the language he used, and the losses he suffered as a result of urban planning policies. Over the course of Sauriol’s career as a conservationist, from the 1940s to the 1990s, the river increas- ingly became a symbol of urban health – specifically, the health of the relationship between urban residents and the natural environment upon which they depend. Drawing from a rich range of sources, including diary entries, published memoirs, and unpublished manuscripts and correspondence, this paper reflects upon the ways that biography can inform histories of place and better our understanding of indi- vidual responses to changing landscapes. Keywords: Toronto, Don River, conservation movement, twentieth century Re´sume´ : Chaque e´te´ de 1927 a` 1968, l’e´cologiste torontois Charles Sauriol et sa famille quittent leur maison de ville pour s’installer dans un chalet rustique quelques kilome`tres plus loin, dans la zone naturelle de la valle´e de la rivie`re Don, au cœur de Toronto. -

Broadview Avenue Planning Study

Character Area D C N R DON VALLEY PARKWAY DON VALLEY DRIVE WO FERN OD C P R GARDENS CHESTER HILL ROAD SI DE DR I V E H IL L PRET ORIA A V . VORIA PRET A O CONNOR DRIVE D HILLSIDE DRIVE OA CAM BRI DGE A VE . ER Y R PO T T C E WOODVILLE AVE. BROADV I EW A V E. TORRENS AVE. DANFORTH AVE. BROADV I EW A V E. MORTIMER AVE. BA TER A VE . VE A TER BA G OW AN A VE . VE A AN OW G BROADVIEW STUDY - URBAN DESIGN GUIDELINES A B FULTON AVE. NEALON AVE. D GAMBLE AVE. BROWNING AVE. COSBURN AVE. ERINDALE AVE. N DEARBOURNE AVENUE East of Broadview Avenue, approximately from Mortimer Avenue to Bater Avenue Character Area D is immediately north of Character Area B on setbacks and front and rear angular planes. Some properties the east side of Broadview Avenue up to Bater Avenue. This area may accommodate a slightly higher density due to the width comprises properties from 1015 to 1129 Broadview Avenue. The and depth of the sites. However, the additional height can only majority of the lots are generally bigger, wider and deeper, with be achieved provided that open spaces and the Neighbourhood existing large one-storey developments or 3-4 storey residential areas at the rear are not impacted negatively. Additional guidance buildings. Buildings in this area back onto residential properties. is provided further below. Due to the existing character, mix of uses, and lot sizes of Maximum Building Height: The maximum height of the Character Area D, the potential for intensification exists. -

2 1 Viewbook

2020-21 VIEWBOOK A WORLD-RENOWNED U of T is a world-renowned University in a celebrated city where knowledge meets achievement, history meets future and ambition meets inspiration. Leading academics from around the world have rated the University of Toronto #1 in Canada and 21st in the world University in Canada University in Canada, and 21st in the world, according to the 2019 Times Higher Education World University Rankings. according to the 2019 QS according to the 2019 Times Higher Education Acknowledgment of Traditional Land World University Rankings. World University Rankings. We wish to acknowledge this land on which the University of Toronto operates. Research University University in Canada for graduate employability For thousands of years it has been the traditional land of the Huron-Wendat, the Seneca, in Canada according to and, most recently, the Mississaugas of the Credit River. Today, this meeting place is still according to both the 2019 QS Graduate Research Infosource 2018. home to many Indigenous people from across Turtle Island and we are grateful to have Employability Rankings and the 2018 Times Higher the opportunity to work on this land. University in Canada according to Education Global University Employability Rankings. Shanghai Jiao Tong University's 2018 Academic Ranking of World Universities. Most innovative university in Canada, according to Reuters' 2018 World's University in Canada, and among Most Innovative Universities rankings. the world's top 10 public universities, according to U.S. News & World Report's 2019 Best Global Universities Rankings. 2 Your Success Starts Here 12 Admissions Timeline 20 U of T St. -

Hillside Drive, South of Gamble Avenue – Green Street Project

STAFF REPORT ACTION REQUIRED Hillside Drive, south of Gamble Avenue – Green Street Project Date: December 7, 2015 To: Toronto and East York Community Council From: Director, Community Planning, Toronto and East York District Wards: Ward 29 – Toronto-Danforth Reference 14-174826 STE 29 TM Number: SUMMARY On August 25, 2014, City Council directed City Planning, Transportation Services, Toronto Water, and Parks, Forestry and Recreation, in consultation with the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority, the Ward Councillor, and area residents, to address matters regarding the Hillside Drive – Green Street Project through the development of several green streetscape options. In addition, City Council directed City Planning staff to report back to Toronto and East York Community Council in 2015 regarding the preferred green streetscape option for Hillside Drive. This report summarizes the efforts of City Planning, Transportation Services, Toronto Water and Parks, Forestry and Recreation to prepare green streetscape options and brings forward a preferred streetscape direction for Hillside Drive. Further, this report recommends a working group format to involve the local community in the implementation of the green streetscape options and outlines potential partnership scenarios and funding sources. Staff report for action – Final Report – Hillside Drive South of Gamble 1 RECOMMENDATIONS The City Planning Division recommends that: 1. City Council adopt the concept for the Hillside Drive Green Streetscape project, as shown in Attachments 3, and subject to refinement through detailed design as set out in recommendation 3; 2. City Council direct Transportation Services to lead the Hillside Drive Green Streets project in all aspects towards implementation, subject to staff and budget resources available in future budgets; 3. -

University of Toronto Archives

University of Toronto Archives Eric Aldwinckle Collection B2000-0030 194- - 196- 0.07 106 items These black and white photographs depict the University of Toronto campus and buildings mainly in 1940s. Included are unique images of houses along St George as well as several winter campus scenes, aerial and elevated views. They were collected by Eric Aldwinckle, who, although best know as a war artist, illustrated Morley Callaghan's book The Varsity Story, as well as several covers and inside drawings for the Varsity Graduate. The photographs in this collection may have been collected to support his work in this capacity. Box File Description Dates Aerial and Elevated Views: /001 (01) Aerial View - St. George Campus before 1956 (02) Aerial View - Varsity Stadium before 1950 (03) View atop U.C. - Cross Chapter House (04) View atop Legislature Building, looking N.W. across Queen's Park (05) View atop U.C. - Looking S. at Convocation Hall (06) View atop U.C. - Looking S. E. at Old Science Library and Legislature Buildings (07) View atop U.C. - Looking N. along Tower Rd. (08) View atop U.C. - Looking down at West Wing of U.C. (09) View atop Park Plaza - Looking south along Queen's Park Circle Campus Views: ca. 194- (10) General winter views (11) Streetscape views and homes along St. George including : 91, 93, 118, 126 142 St. George St. Buildings ca. 194- (12) Annesley Hall (13) Archives Building (14) Banting and Best Institute (15) Biology Building (16) Botanical Greenhouses (17) Convocation Hall (18) David Dunlop Observatory (19) Dentistry Building University of Toronto Archives Eric Aldwinckle Collection B2000-0030 Box File Description Dates (20) Electrical Building (21) Emmanuel College (22) Engineering Building (23) Forestry Building (24) Household Science Building (25) Hygiene Building (26) Knox College (27) Mechanical Building (28) Old Medical Building (29) Mining Building (30) Ontario College of Education (31) Physics Building (32) Press Building (33) Queen's Park (33a) S.A.C.