Controlling Banker's Bonuses: Efficient Regulation Or Politics of Envy?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alabama Credit Unions & Banker Myths

Alabama Credit Unions & Banker Myths Bumper profits and a massive concentration of market share aren’t enough for Alabama’s bankers. They want more. And they seem willing to do anything to get it. Indeed, banking industry publications recently distributed to state policy-makers use anecdotes, half-truths, and innuendo in an all-out assault the state’s credit unions. While its true that Alabama credit unions are growing, they aren’t, as bankers suggest, taking over the world. They remain true to their original purpose. And they certainly aren’t harming the state’s banks. Growth: Banking institution deposits in Alabama grew by $10.2 billion in the 88% ISN'T ENOUGH? five years ending June 2003. Since 1998 Alabama banking deposits have grown Alabama Bankers Want More 22% more than the total growth Market Share! recorded by the state’s’ credit unions (Mid-Year 2003 Deposits) since credit unions began operating in the state in 1927! Largest 10 Banks Market Share: Banking institutions 58% control 88% of all financial institution Smaller deposits in the state of Alabama – a CUs market share that is virtually unchanged 5% over the past decade. Small banks in Alabama have a lot more Largest 10 significant competitive threats to worry CUs Smaller 7% about than the threat of credit union Banks competition. Indeed, at the mid-year 30% 2003, the largest 10 banking institutions control 58% of total deposits in the state (or 66% of total banking deposits). In contrast, credit unions control just 12% of the market and the largest 10 credit unions control just 7% of the deposit market in Alabama. -

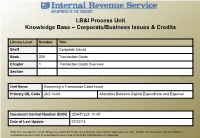

LB&I Process Unit Knowledge Base – Corporate/Business Issues & Credits

LB&I Process Unit Knowledge Base – Corporate/Business Issues & Credits Library Level Number Title Shelf Corporate Issues Book 225 Transaction Costs Chapter 1 Transaction Costs Overview Section Unit Name Examining a Transaction Costs Issue Primary UIL Code 263.14-00 Allocation Between Capital Expenditure and Expense Document Control Number (DCN) CDA/P/225_01-01 Date of Last Update 07/02/18 Note: This document is not an official pronouncement of law, and cannot be used, cited or relied upon as such. Further, this document may not contain a comprehensive discussion of all pertinent issues or law or the IRS's interpretation of current law. DRAFT Table of Contents (View this PowerPoint in “Presentation View” to click on the links below) Process Overview Detailed Explanation of the Process Process Applicability Summary of Process Steps . Step 1 – Proper Legal Entity . Step 2 – Facilitative Costs . Step 3 – Treatment of Facilitative Costs 2 DRAFT Table of Contents (cont’d) (View this PowerPoint in “Presentation View” to click on the links below) Definitions Other Considerations / Impact to Audit Index of Referenced Resources Training and Additional Resources Glossary of Terms and Acronyms Index of Related Practice Units 3 DRAFT Process Overview Examining a Transaction Costs Issue When executing a business transaction, a taxpayer may incur legal fees, accounting fees, consulting fees, investment advisory service fees and other transaction costs. If the cost facilitates a transaction described in Treas. Reg. 1.263(a)-5(a), the taxpayer must capitalize the cost. Transactions described in Treas. Reg. 1.263(a)-5(a) include acquiring or selling a trade or business, or changing a company’s capital structure. -

The Code of Hammurabi: an Economic Interpretation

International Journal of Business and Social Science Vol. 2 No. 8; May 2011 The Code of Hammurabi: An Economic Interpretation K.V. Nagarajan Department of Economics, School of Commerce and Administration Laurentian University, Sudbury Canada E-mail: [email protected], Fax: 705-675-4886 Introduction Hammurabi was the ruler of Babylon from 1792 B.C. to 1750 B.C1. He is much celebrated for proclaiming a set of laws, called the Code of Hammurabi (The Code henceforward). The Code was written in the Akkadian language and engraved on black diorite, measuring about two-and-a-quarter meters. The tablet is on display in the Louvre, Paris. The stone carving on which the laws are written was found in 1901-1902 by French archeologists at the Edomite capital Susa which is now part of the Kuzhisthan province in Iran. The Code was determined to be written circa 1780 B.C. Although there are other codes preceding it2, The Code is considered the first important legal code known to historians for its comprehensive coverage of topics and wide-spread application. It has been translated and analyzed by historians, legal and theological scholars (Goodspeed, 1902; Vincent, 1904; Duncan, 1904; Pfeiffer, 1920; Driver and Miles, 1952). The Code is well- known for embodying the principle of lex talionis (“eye for an eye”) which is described as a system of retributive justice. However, The Code is also much more complex than just describing offenses and punishments and not all punishments are of the retributive kind. The Code has great relevance to economists. However, very few studies have been undertaken from an economic or economic thought point of view. -

The Birth of Partnership Systems in Renaissance Florence1 John F

Chapter 6 Transposition and Refunctionality: The Birth of Partnership Systems in 1 Renaissance Florence John F. Padgett Inventions of any sort are hard to understand. They seem to come out of the blue, a rupture with the past, yet close investigation always reveals historical roots. Individual geniuses sometimes create them, but is “genius” just our celebratory label for a process that worked, which we do not understand? To proffer a tentative distinction: innovations improve on existing ways (i.e, activities, conceptions and purposes) of doing things, while inventions change the ways things are done. Under this definition, the key to classifying something as an invention is the degree to which it reverberates out to alter the interacting system of which it is a part. To some extent we understand micrologics of combination and recombination.2 Yet the invention puzzle is that some of these innovative recombinations cascade out to reconfigure entire interlinked ecologies of “ways of doing things,” whereas most innovations do not. The poisedness of a system to reconfiguration by an invention is as much a part of the phenomenon to be explained as is the system’s production of the invention itself. Invention “in the wild” cannot be understood through abstracting away from concrete social context, because inventions are permutations of that context.3 But to make progress in understanding discontinuous change we need to embed our analysis of transformation in the routine dynamics of actively self-reproducing social contexts, where constitutive elements and relations are generated and reinforced. 1 This chapter is an abridged version (40% cut) of John F. -

II. the Game of Credit: a Model Consider a Simple Two-Stage Game

II. The game of credit: a model Consider a simple two-stage game with complete but imperfect information. There are two players: the king and a banker. They interact as follows: First, the king borrows from the banker a certain amount of money K and several financial services F, offering him a contract (“asiento”). The asiento signed between a lender and the sovereign takes the form of a promise by the sovereign to repay the principal of the loan K plus interest, i, and a non-monetary reward, T. However, the lender will not receive the whole monetary profit (K plus i) promised in the contract at the end of the game. The sovereign will retain temporarily a portion g1 of the total monetary gains of the banker. This amount will be paid as debt in the future. The opportunity to borrow from a banker is an important benefit for the king and it is represented by the variable called V. This means how much the relationship with the banker is important for the king. V modifies the king’s payoffs. When the king does not need bankers, V is negative, and the contrary makes V positive. We assume that V has a large value because the king always needs credit and financial services from the bankers. The value of V is linked to the conditions that allow the king to establish a relationship with the banker. They are political, economic and social factors. Among the most important are the revenues available to borrow by the Monarchy. The rest of variables in this game are fixed by the negotiation between king and banker in a contract of credit and they are well known by both players (See all variables in appendix I). -

Travel Insurer Gets Picky January Next Year Will Be Subject to Enhanced Security Requirements

NOW INSIDE: privatehealthcarenews GLOBAL HEALTHCARE • IPMI • CORPORATE BENEFITS Page 24 Page 26 Page 46 Page 22 Page 32 ESSENTIAL READING FOR TRAVEL INSURANCE INDUSTRY PROFESSIONALS noveMBER 2008 • ISSUE 94 Not so routine transport In the last issue of ITIJ, we reported on a patient who was denied boarding by a pilot at Ercan airport in North Cyprus, an independent republic of Turkey. Less than two weeks later, a repatriation was held up at Istanbul airport. ITIJ tells Air Ambulance Worldwide’s bizarre story On 15 September this year, John Ray of Air Ambulance Worldwide was sent on a flight to escort a 26-year-old male, Reid Sanders, from the German Hospital in Istanbul, Turkey, to his home residence in Bend, Oregon. Sanders was an entertainer on a cruise ship, and had a history of diabetes. Having fallen unresponsive and unalert he had been transported via ground ambulance from the cruise ship port in Istanbul to the German Hospital. After a week in the hospital, Sanders’ doctors determined that he was fit to fly home, and could follow up with his personal care physician upon arrival. His mother and sister had come to Istanbul to accompany him home, and on the morning of 18 September, they all travelled with Ray to the airport. They arrived several hours early, in the small hours of the morning, and Sanders’ mother and sister went through to the departure gate whilst Ray and Sanders rearranged Sanders’ heavy luggage in order to avoid excessive weight charges. After the luggage was continued on page 6 Visa changes to US travel Important information for air ambulance companies and medical escorts: under the terms and conditions of the US Visa Waiver Program, all international travellers who wish to enter to the US from 1 Travel insurer gets picky January next year will be subject to enhanced security requirements. -

Nothing Left of Indopco: Let's Keep It That Way!

Florida State University Law Review Volume 29 Issue 1 Article 6 2001 Nothing Left of Indopco: Let's Keep it that Way! Jezabel Llorente [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jezabel Llorente, Nothing Left of Indopco: Let's Keep it that Way!, 29 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. (2001) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol29/iss1/6 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW DESCENT Aviam Soifer VOLUME 29 FALL 2001 NUMBER 1 Recommended citation: Aviam Soifer, Descent, 29 FLA. ST. U. L. REV. 269 (2001). FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW NOTHING LEFT OF INDOPCO: LET’S KEEP IT THAT WAY! Jezabel Llorente VOLUME 29 FALL 2001 NUMBER 1 Recommended citation: Jezabel Llorente, Nothing Left of Indopco: Let’s Keep it That Way!, 29 FLA. ST. U. L. REV. 277 (2001). NOTHING LEFT OF INDOPCO: LET’S KEEP IT THAT WAY! JEZABEL LLORENTE* I. INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................... 277 II. THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN CURRENT DEDUCTION AND CAPITAL EXPENSE .... 279 III. INDOPCO’S FAMILY TREE .................................................................................. 281 IV. THE IRS’S AGGRESSIVE POST-INDOPCO POSITIONS ......................................... 284 A. The IRS’s Position in PNC Bancorp ............................................................ 285 B. The IRS’s Position in Wells Fargo............................................................... 285 C. The IRS’s Position in Hostile Takeovers...................................................... 287 V. THE IRS’S AGGRESSIVE POST-INDOPCO POSITIONS PROMOTE BAD POLICY... -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

Case 1:12-cv-00375-LJO-SKO Document 1 Filed 03/12/12 Page 1 of 50 1 KESSLER TOPAZ MELTZER & CHECK, LLP 2 Ramzi Abadou (Bar No. 222567) 580 California Street, Suite 1750 3 San Francisco, CA 94104 4 Telephone: (415) 400-3000 Facsimile: (415) 400-3001 5 [email protected] 6 Counsel for Plaintiff 7 [Additional counsel listed on signature page] 8 9 10 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 11 EASTERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 12 13 LUCAS E. MCCARN, individually and on behalf ) Civil Action No.: of all others similarly situated, ) 14 ) 15 Plaintiff, ) ) 16 v. ) CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT ) 17 HSBC USA, INC., HSBC BANK USA, N.A., ) HSBC MORTGAGE CORPORATION, HSBC ) 18 REINSURANCE (USA) INC., UNITED ) JURY TRIAL DEMANDED 19 GUARANTY RESIDENTIAL INSURANCE CO., ) PMI MORTGAGE INSURANCE CO., ) 20 GENWORTH MORTGAGE INSURANCE ) CORP., REPUBLIC MORTGAGE INSURANCE ) 21 CO., MORTGAGE GUARANTY INSURANCE ) CORP., and RADIAN GUARANTY INC. ) 22 ) 23 Defendants. ) 24 25 26 27 28 Case 1:12-cv-00375-LJO-SKO Document 1 Filed 03/12/12 Page 2 of 50 1 INTRODUCTION 2 1. Defendants HSBC USA, Inc. (“HSBC USA”), HSBC Bank USA, N.A. (“HSBC 3 Bank”) and HSBC Mortgage Corp. (“HSBC Mortgage”), together with their affiliated reinsurer, 4 Defendant HSBC Reinsurance (USA), Inc. (“HSBC RE”) (collectively, “HSBC”), have acted in 5 concert with Defendants United Guaranty Residential Insurance Co., PMI Mortgage Insurance Co., 6 Genworth Mortgage Insurance Corp., Republic Mortgage Insurance Co., Mortgage Guaranty 7 Insurance Corp. and Radian Guaranty Inc. (collectively, the “Private Mortgage Insurers”) (together 8 with HSBC, “Defendants”) to effectuate a captive reinsurance scheme whereby, in violation of the 9 Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act of 1974 (“RESPA”): (a) illegal referral payments in the form of 10 purported reinsurance premiums were paid by the Private Mortgage Insurers to HSBC RE; and (b) 11 HSBC RE received an unlawful split of private mortgage insurance premiums paid by the Private 12 Mortgage Insurers’ customers referred by HSBC entities. -

Participant List

Participant List 10/20/2019 8:45:44 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Ramil Abbasov Chariman of the Managing Spektr Socio-Economic Azerbaijan Board Researches and Development Public Union Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Amr Abdallah Director, Gulf Programs Educaiton for Employment - United States EFE HAGAR ABDELRAHM African affairs & SDGs Unit Maat for Peace, Development Egypt AN Manager and Human Rights Abukar Abdi CEO Juba Foundation Kenya Nabil Abdo MENA Senior Policy Oxfam International Lebanon Advisor Mala Abdulaziz Executive director Swift Relief Foundation Nigeria Maryati Abdullah Director/National Publish What You Pay Indonesia Coordinator Indonesia Yussuf Abdullahi Regional Team Lead Pact Kenya Abdulahi Abdulraheem Executive Director Initiative for Sound Education Nigeria Relationship & Health Muttaqa Abdulra'uf Research Fellow International Trade Union Nigeria Confederation (ITUC) Kehinde Abdulsalam Interfaith Minister Strength in Diversity Nigeria Development Centre, Nigeria Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Shahlo Abdunabizoda Director Jahon Tajikistan Shontaye Abegaz Executive Director International Insitute for Human United States Security Subhashini Abeysinghe Research Director Verite -

History of Mortgage Finance with an Emphasis on Mortgage Insurance

History of Mortgage Finance With an Emphasis on Mortgage Insurance Thomas N. Herzog, Ph.D., ASA Copyright 2009 by the Society of Actuaries. All rights reserved by the Society of Actuaries. Permission is granted to make brief excerpts for a published review. Permission is also granted to make limited numbers of copies of items in this monograph for personal, internal, classroom or other instructional use, on condition that the foregoing copyright notice is used so as to give reasonable notice of the Society’s copyright. This consent for free limited copying without prior consent of the Society does not extend to making copies for general distribution, for advertising or promotional purposes, for inclusion in new collective works or for resale. Chapter 1 – Introduction This is a history of mortgage guarantee insurance in the United States. In order to understand the essence of this, it is crucial to understand: • who is lending the money that is being guaranteed, • who is regulating the lender, and • who is regulating the mortgage insurer. Hence, we need to examine, at least briefly, the history of banks and banking regulation in the United States. Here we begin with the establishment of the First Bank of the United States in 1791. The first federal banking regulator was the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, within the U.S. Department of the Treasury. Finally, we are able to trace the existence of the first mortgage guarantee insurance company as back as far as 1900 or so. The private mortgage insurers are typically regulated by one or more state insurance department, particularly by the one in whose state the company is domiciled. -

Perseverance of Banker Ladies in the Slums

Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics 84:4 2013 pp. 423–442 AUTHOR’S COPY – THIS IS A DRAFT VERSION – PLEASE CITE IF YOU USE IT THE BLACK SOCIAL ECONOMY: PERSEVERANCE OF BANKER LADIES IN THE SLUMS by ∗ Caroline SHENAZ HOSSEIN York University, Toronto, Canada ABSTRACT: In a neoliberal world where commercial financial services are con- trolled by elites, poor Black women in the slums are usually excluded from financial programs – even microfinance ones. In my empirical study of 491 people in Jamaica, Guyana and Haiti, I argue that the participation in informal banking systems by the poor, not only provides coping tools for livelihood survival, but banker ladies insert a program of social connectedness and political action when they organize these local resources. Banker ladies have a clear social justice agenda: to validate the business activities of marginalized people. Informal banks are a counter project to neoliberalism because it is focused on the collective, where poor Afro-Caribbean women are creating alternative financial programs that are squarely part of the social economy. Keywords: Black women, exclusion, informal banks, gender, inequality, politics, social justice. La economı´a social sumergida: perseverancia de las mujeres banqueras en las chabolas En un mundo neoliberal en el que los servicios financieros comerciales son controlados por e´lites, las mujeres pobres negras de las chabolas son generalmente excluidas de los programas financieros, incluso de las microfinanzas. En su estudio emp´ırico, sustentado sobre 491 personas en Jamaica, Guayana y Hait´ı, el autor explica que la participacio´n de los pobres en los sistemas bancarios informales les permite sobrevivir, pero tambie´n les ofrece posibilidades de integracio´n social y de accio´n pol´ıtica, gracias a los modos de gestio´n de los recursos locales propuestos por las mujeres banqueras. -

Activities Permissible for a National Bank, Cumulative, 2011 Annual

Activities Permissible for National Banks and Federal Savings Associations, Cumulative October 2017 Contents General Banking Activities .......................................................................................................... 3 Branching ................................................................................................................................... 3 Consulting and Financial Advice ............................................................................................... 9 Corporate Governance and Structure ....................................................................................... 12 Correspondent Services ............................................................................................................ 26 Finder Activities ....................................................................................................................... 27 Leasing ..................................................................................................................................... 29 Lending..................................................................................................................................... 32 Other Activities ........................................................................................................................ 43 Payment Services ..................................................................................................................... 49 Fiduciary Activities ...................................................................................................................