The Birth of Partnership Systems in Renaissance Florence1 John F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alabama Credit Unions & Banker Myths

Alabama Credit Unions & Banker Myths Bumper profits and a massive concentration of market share aren’t enough for Alabama’s bankers. They want more. And they seem willing to do anything to get it. Indeed, banking industry publications recently distributed to state policy-makers use anecdotes, half-truths, and innuendo in an all-out assault the state’s credit unions. While its true that Alabama credit unions are growing, they aren’t, as bankers suggest, taking over the world. They remain true to their original purpose. And they certainly aren’t harming the state’s banks. Growth: Banking institution deposits in Alabama grew by $10.2 billion in the 88% ISN'T ENOUGH? five years ending June 2003. Since 1998 Alabama banking deposits have grown Alabama Bankers Want More 22% more than the total growth Market Share! recorded by the state’s’ credit unions (Mid-Year 2003 Deposits) since credit unions began operating in the state in 1927! Largest 10 Banks Market Share: Banking institutions 58% control 88% of all financial institution Smaller deposits in the state of Alabama – a CUs market share that is virtually unchanged 5% over the past decade. Small banks in Alabama have a lot more Largest 10 significant competitive threats to worry CUs Smaller 7% about than the threat of credit union Banks competition. Indeed, at the mid-year 30% 2003, the largest 10 banking institutions control 58% of total deposits in the state (or 66% of total banking deposits). In contrast, credit unions control just 12% of the market and the largest 10 credit unions control just 7% of the deposit market in Alabama. -

Controlling Banker's Bonuses: Efficient Regulation Or Politics of Envy?

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Matthews, Kent; Matthews, Owen Working Paper Controlling banker's bonuses: Efficient regulation or politics of envy? Cardiff Economics Working Papers, No. E2009/27 Provided in Cooperation with: Cardiff Business School, Cardiff University Suggested Citation: Matthews, Kent; Matthews, Owen (2009) : Controlling banker's bonuses: Efficient regulation or politics of envy?, Cardiff Economics Working Papers, No. E2009/27, Cardiff University, Cardiff Business School, Cardiff This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/65789 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der -

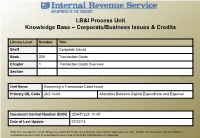

LB&I Process Unit Knowledge Base – Corporate/Business Issues & Credits

LB&I Process Unit Knowledge Base – Corporate/Business Issues & Credits Library Level Number Title Shelf Corporate Issues Book 225 Transaction Costs Chapter 1 Transaction Costs Overview Section Unit Name Examining a Transaction Costs Issue Primary UIL Code 263.14-00 Allocation Between Capital Expenditure and Expense Document Control Number (DCN) CDA/P/225_01-01 Date of Last Update 07/02/18 Note: This document is not an official pronouncement of law, and cannot be used, cited or relied upon as such. Further, this document may not contain a comprehensive discussion of all pertinent issues or law or the IRS's interpretation of current law. DRAFT Table of Contents (View this PowerPoint in “Presentation View” to click on the links below) Process Overview Detailed Explanation of the Process Process Applicability Summary of Process Steps . Step 1 – Proper Legal Entity . Step 2 – Facilitative Costs . Step 3 – Treatment of Facilitative Costs 2 DRAFT Table of Contents (cont’d) (View this PowerPoint in “Presentation View” to click on the links below) Definitions Other Considerations / Impact to Audit Index of Referenced Resources Training and Additional Resources Glossary of Terms and Acronyms Index of Related Practice Units 3 DRAFT Process Overview Examining a Transaction Costs Issue When executing a business transaction, a taxpayer may incur legal fees, accounting fees, consulting fees, investment advisory service fees and other transaction costs. If the cost facilitates a transaction described in Treas. Reg. 1.263(a)-5(a), the taxpayer must capitalize the cost. Transactions described in Treas. Reg. 1.263(a)-5(a) include acquiring or selling a trade or business, or changing a company’s capital structure. -

The Code of Hammurabi: an Economic Interpretation

International Journal of Business and Social Science Vol. 2 No. 8; May 2011 The Code of Hammurabi: An Economic Interpretation K.V. Nagarajan Department of Economics, School of Commerce and Administration Laurentian University, Sudbury Canada E-mail: [email protected], Fax: 705-675-4886 Introduction Hammurabi was the ruler of Babylon from 1792 B.C. to 1750 B.C1. He is much celebrated for proclaiming a set of laws, called the Code of Hammurabi (The Code henceforward). The Code was written in the Akkadian language and engraved on black diorite, measuring about two-and-a-quarter meters. The tablet is on display in the Louvre, Paris. The stone carving on which the laws are written was found in 1901-1902 by French archeologists at the Edomite capital Susa which is now part of the Kuzhisthan province in Iran. The Code was determined to be written circa 1780 B.C. Although there are other codes preceding it2, The Code is considered the first important legal code known to historians for its comprehensive coverage of topics and wide-spread application. It has been translated and analyzed by historians, legal and theological scholars (Goodspeed, 1902; Vincent, 1904; Duncan, 1904; Pfeiffer, 1920; Driver and Miles, 1952). The Code is well- known for embodying the principle of lex talionis (“eye for an eye”) which is described as a system of retributive justice. However, The Code is also much more complex than just describing offenses and punishments and not all punishments are of the retributive kind. The Code has great relevance to economists. However, very few studies have been undertaken from an economic or economic thought point of view. -

II. the Game of Credit: a Model Consider a Simple Two-Stage Game

II. The game of credit: a model Consider a simple two-stage game with complete but imperfect information. There are two players: the king and a banker. They interact as follows: First, the king borrows from the banker a certain amount of money K and several financial services F, offering him a contract (“asiento”). The asiento signed between a lender and the sovereign takes the form of a promise by the sovereign to repay the principal of the loan K plus interest, i, and a non-monetary reward, T. However, the lender will not receive the whole monetary profit (K plus i) promised in the contract at the end of the game. The sovereign will retain temporarily a portion g1 of the total monetary gains of the banker. This amount will be paid as debt in the future. The opportunity to borrow from a banker is an important benefit for the king and it is represented by the variable called V. This means how much the relationship with the banker is important for the king. V modifies the king’s payoffs. When the king does not need bankers, V is negative, and the contrary makes V positive. We assume that V has a large value because the king always needs credit and financial services from the bankers. The value of V is linked to the conditions that allow the king to establish a relationship with the banker. They are political, economic and social factors. Among the most important are the revenues available to borrow by the Monarchy. The rest of variables in this game are fixed by the negotiation between king and banker in a contract of credit and they are well known by both players (See all variables in appendix I). -

Travel Insurer Gets Picky January Next Year Will Be Subject to Enhanced Security Requirements

NOW INSIDE: privatehealthcarenews GLOBAL HEALTHCARE • IPMI • CORPORATE BENEFITS Page 24 Page 26 Page 46 Page 22 Page 32 ESSENTIAL READING FOR TRAVEL INSURANCE INDUSTRY PROFESSIONALS noveMBER 2008 • ISSUE 94 Not so routine transport In the last issue of ITIJ, we reported on a patient who was denied boarding by a pilot at Ercan airport in North Cyprus, an independent republic of Turkey. Less than two weeks later, a repatriation was held up at Istanbul airport. ITIJ tells Air Ambulance Worldwide’s bizarre story On 15 September this year, John Ray of Air Ambulance Worldwide was sent on a flight to escort a 26-year-old male, Reid Sanders, from the German Hospital in Istanbul, Turkey, to his home residence in Bend, Oregon. Sanders was an entertainer on a cruise ship, and had a history of diabetes. Having fallen unresponsive and unalert he had been transported via ground ambulance from the cruise ship port in Istanbul to the German Hospital. After a week in the hospital, Sanders’ doctors determined that he was fit to fly home, and could follow up with his personal care physician upon arrival. His mother and sister had come to Istanbul to accompany him home, and on the morning of 18 September, they all travelled with Ray to the airport. They arrived several hours early, in the small hours of the morning, and Sanders’ mother and sister went through to the departure gate whilst Ray and Sanders rearranged Sanders’ heavy luggage in order to avoid excessive weight charges. After the luggage was continued on page 6 Visa changes to US travel Important information for air ambulance companies and medical escorts: under the terms and conditions of the US Visa Waiver Program, all international travellers who wish to enter to the US from 1 Travel insurer gets picky January next year will be subject to enhanced security requirements. -

The Rhetoric of Work in Leon Battista Alberti's Writings

Rhetorics of work / edited by Yannis Yannitsiotis, Dimitra Lampropoulou, Carla Salva- terra. - Pisa : Plus-Pisa university press, c2008. – (Thematic work group. 4, Work, gender and society ; 3) 331.01 (21.) 1. Lavoro – Concetto - Europa I. Lampropoulou, Dimitra II. Salvaterra, Carla III. Yannitsiotis, Yannis CIP a cura del Sistema bibliotecario dell’Università di Pisa This volume is published thanks to the support of the Directorate General for Research of the European Commission, by the Sixth Framework Network of Excellence CLIOHRES.net under the contract CIT3-CT-2005-006164. The volume is solely the responsibility of the Network and the authors; the European Community cannot be held responsible for its contents or for any use which may be made of it. Cover: André Lhote (1885-1962), Study for the School of Arts and Crafts, painting, Musée de l’Annonciade, Saint- Tropez. © 1990 PhotoScala, Florence. © 2008 CLIOHRES.net The materials published as part of the CLIOHRES Project are the property of the CLIOHRES.net Consortium. They are available for study and use, provided that the source is clearly acknowledged. [email protected] - www.cliohres.net Published by Edizioni Plus – Pisa University Press Lungarno Pacinotti, 43 56126 Pisa Tel. 050 2212056 – Fax 050 2212945 [email protected] www.edizioniplus.it - Section “Biblioteca” Member of ISBN: 978-88-8492-555-8 Linguistic Editing Ralph Nisbet Informatic Editing Răzvan Adrian Marinescu The Rhetoric of Work in Leon Battista Alberti’s Writings Claudia Bertazzo University of Padua ABSTRACT One source of interest in doing research on Leon Battista Alberti is to see how a man of multiple talents from the 15th-century elites viewed the world of work, including craftsmanship and manual work in the broadest sense. -

Political Conspiracy in Florence, 1340-1382 A

POLITICAL CONSPIRACY IN FLORENCE, 1340-1382 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Robert A. Fredona February 2010 © 2010 Robert A. Fredona POLITICAL CONSPIRACY IN FLORENCE, 1340-82 Robert A. Fredona, Ph. D. Cornell University 2010 This dissertation examines the role of secret practices of opposition in the urban politics of Florence between 1340 and 1382. It is based on a wide variety of printed and archival sources, including chronicles, judicial records, government enactments, the records of consultative assemblies, statutes, chancery letters, tax records, private diaries and account books, and the ad hoc opinions (consilia) of jurists. Over the course of four chapters, it presents three major arguments: (1) Conspiracy, a central mechanism of political change and the predominant expression of political dissent in the city, remained primarily a function of the factionalism that had shattered the medieval commune, although it was now practiced not as open warfare but secret resistance. (2) Conspiracies were especially common when the city was ruled by popular governments, which faced almost constant conspiratorial resistance from elite factions that been expelled from the city or had had their political power restricted, while also inspiring increased worker unrest and secret labor organization. (3) Although historians have often located the origins of the “state” in the late medieval and early Renaissance cities of northern and central Italy, the prevalence of secret political opposition, the strength of conspirators and their allies, and the ability of conspiratorial networks, large worker congregations, and even powerful families to vie with weak regimes for power and legitimacy seriously calls this into question. -

Book Review of Merchant Writers: Florentine Memoirs from the Middle Ages and Renaissance Brian Jeffrey Maxson East Tennessee State University, [email protected]

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University ETSU Faculty Works Faculty Works 1-1-2016 Book Review of Merchant Writers: Florentine memoirs from the Middle Ages and Renaissance Brian Jeffrey Maxson East Tennessee State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etsu-works Part of the European History Commons Citation Information Maxson, Brian Jeffrey. 2016. Book Review of Merchant Writers: Florentine memoirs from the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Sixteenth Century Journal. Vol.67(4). 1114-1116. This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in ETSU Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Book Review of Merchant Writers: Florentine memoirs from the Middle Ages and Renaissance Copyright Statement This document was published with permission by the journal. It was originally published in Sixteenth Century Journal. This review is available at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University: https://dc.etsu.edu/etsu-works/2681 This material may be protected by copyright law (Title 17 U.S. Code) 1114 Sixteenth Century Journal XLVIl/4 (2016) inspiration for Homer), and this entails altering texts so that the weak-tongued Thersites becomes an artful satirist. Milton's use of Homer (chap. 5), more overtly theological and political in tone, takes aim at both royalists and the failed commonwealth. For Milton the Iliad becomes the antidote to bickering councils whose ineptitude leads to a return of mon archy. -

The Intellectual Renaissance in Italy New Era? Both Positions Can Be Dcfended

Michelangelo's Creation of Adam on the Sist¡ne Chapel ceiling CHAPTER OUTLINE CRITICAL THINKINC AND FOCUS QUESTTONS l-\ Ho* did Renaissance art and the humanist Meaning and Characteristics of the Italian { -ov"-cnt reflect the potitical, economic, and Renaissance social developments of the period? f) What characteristics distinguish the Renaissance fiom æ \< th" Middle Ages? CONNECTIONS TO TODAY The Making of Renaissance Society How does the concept of the Renaissance have |-\| wirat maior social changes occurred during the relevance to the early twenty-fust century? { R"r,.irr*."1 a The Italian States in the Renaissance How did MachiavelÌi's works reflect the political a realities of Renaissance ltaly? WERE THE FOURTEENTH and fifteenth cenruries a continuation of the Middle Ages or the beginning of a The Intellectual Renaissance in Italy new era? Both positions can be dcfended. Although the what was humanism, and what effect did it have on ¡fì disintegrative pattems of the fourteenth century phllosophy, education, aftirudes toward politics, and the { continued into the fifteenth, at the same time there were writing of history? elements of recovery that made the fifteenth century a The Artistic Renaissance period of significant political, economic, artistic, and intellectual change . The humanists or intellectuals of the wtrat were the chief characteristics of Renaissance art, ¡J age called their period (from the mid-fourteenth to the :(. *d how did it differ in Italy and northern Europe? mid-sixtecnth century) an age of rebirth, believir-rg that The European State in the Renaissance thcy had rcstored arts and lettels to new glory aftel they ¡-\ Whv do historians sometimes refer to the monarchies had been "neglected" or "dead" for centuries. -

Timeline Principal Events in the Histories of Florence and the House of Rucellai

Timeline Principal events in the histories of Florence and the house of Rucellai Neolithic period Arno River valley first settled 9th–8th century bce Etruscans establish a settlement (Viesul, now known as Fiesole) on a hill above the valley 59 bce Julius Caesar establishes a Roman colony for retired soldiers on the northern bank of the Arno (Florentia, now known as Florence) 2nd century ce Population: c.10,000 393 City’s first Christian basilica, San Lorenzo, consecrated as its cathedral by Saint Ambrose 405 Siege of Florence, part of a succession of Gothic invasions of the Roman Empire 5th century Church of Santa Reparata constructed within the Roman walls on the site of the present cathedral Late 6th century City falls to the Lombards, becoming part of the Lombardic Duchy of Tuscany 774 City conquered by Charlemagne; Carolingian era ushers in a period of urban revival Late 8th century City walls expanded 978 Badia Fiorentina, a Benedictine Abbey, founded by Willa, widow of Uberto, Margrave of Tuscany 996 First Ponte Vecchio built near the site of the Roman-era bridge 1018 Mercato Nuovo built on the site of the old Roman forum Basilica of San Miniato al Monte built on highest point in Florence Population: c.5,000 1115 Florence achieves de facto self-government with the establishment of a comune (confirmed by the Holy Roman Emperor in 1183) xv Timeline 1128 Construction finished on the Baptistery, built on the site of a sixth- or seventh-century octagonal structure, itself built on a structure dating to the Roman period c.1150 Arte di -

Gregorio Dati (13621435) and the Limits of Individual Agency

Epurescu-Pascovici, I Gregorio Dati (13621435) and the Limits of Individual Agency pp. 297-325 Epurescu-Pascovici, I, (2006) "Gregorio Dati (13621435) and the Limits of Individual Agency", Medieval history journal, 9, 2, pp.297-325 Staff and students of University of Warwick are reminded that copyright subsists in this extract and the work from which it was taken. This Digital Copy has been made under the terms of a CLA licence which allows you to: • access and download a copy; • print out a copy; Please note that this material is for use ONLY by students registered on the course of study as stated in the section below. All other staff and students are only entitled to browse the material and should not download and/or print out a copy. This Digital Copy and any digital or printed copy supplied to or made by you under the terms of this Licence are for use in connection with this Course of Study. You may retain such copies after the end of the course, but strictly for your own personal use. All copies (including electronic copies) shall include this Copyright Notice and shall be destroyed and/or deleted if and when required by University of Warwick. Except as provided for by copyright law, no further copying, storage or distribution (including by e-mail) is permitted without the consent of the copyright holder. The author (which term includes artists and other visual creators) has moral rights in the work and neither staff nor students may cause, or permit, the distortion, mutilation or other modification of the work, or any other derogatory treatment of it, which would be prejudicial to the honour or reputation of the author.