Academic Freedom: the Global Challenge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China Media Bulletin

Issue No. 130: October 2018 CHINA MEDIA BULLETIN Headlines ANALYSIS Amid U.S.-China Tension, Beijing’s Propaganda Machine Charges On P2 IN THE NEWS • New rules and innovation enhance police surveillance P4 • Xinjiang crackdown: Writers jailed, foreign investment questioned, state responds to outcry P5 • Censorship updates: Online religious content, foreign television, VPN crackdown P7 • Hong Kong: Expulsion of ‘Financial Times’ editor undermines press freedom P8 • Beyond China: Africa influence, US campuses, CCTV heckler, Malaysia Uighurs, motherboard chips P8 FEATURED PUSHBACK #MeToo Movement P10 WHAT TO WATCH FOR P11 TAKE ACTION P12 IMAGE OF THE MONTH Skeletons in the Communist Party’s closet This seemingly innocuous image was shared 12,000 times on Sina Weibo within 11 hours on September 23 before being deleted by censors. The caption accompanying the image said it portrayed a caving expedition in Guilin, Guangxi Province, that discovered the skeletons of 93 people who were killed at the height of the Cultural Revolution: “From October 2 to 3, 1967 … the militia battalion commander of Sanjiang Commune … pushed 93 local rich people into the bottomless sinkhole…. One of the big landlord families had a total of 76 people, young and old; all were all pushed into the pit, including married daughters and their children. The youngest one is less than one year old and the oldest is 65 years old.” Credit: Weiboscope Visit http://freedomhou.se/cmb_signup or email [email protected] to subscribe or submit items. CHINA MEDIA BULLETIN: OCTOBER 2018 ANALYSIS Amid U.S.-China Tension, Beijing’s Propaganda Machine Charges On By Sarah Cook The regime’s recent media interventions may have unintended consequences. -

Volume 25, 2016 D Nott-Law Jnl25 Cover Nott-Law Cv 25/07/2016 13:18 Page 2

d_Nott-law jnl25_cover_Nott-Law_cv 25/07/2016 13:18 Page 1 N O T T I N In this issue: G H A M L Helen O’Nions A EDITORIAL W J O U R N A ARTICLES L How Many Contracts in an Auction Sale? James Brown and Mark Pawlowski NOTTINGHAM LAW JOURNAL The Legal Prospective Force of Constitutional Courts Decisions: Reflections from the Constitutional Jurisprudence of Kosovo and Beyond Visar Morina Journal of Nottingham Law School Don’t Take Away My Break-Away: Balancing Regulatory and Commercial Interests in Sport Simon Boyes The Creative Identity and Intellectual Property Janice Denoncourt THEMATIC ARTICLES: PERSPECTIVES ON THE ISLAMIC FACE VEIL Introduction Tom Lewis Articles S.A.S v France : A Reality Check Eva Brems Human Rights, Identity and the Legal Regulation of Dress Jill Marshall No Face Veils in Court Felicity Gerry QC Face Veils and the Law: A Critical Reflection Samantha Knights The Veiled Lodger – A Reflection on the Status of R v D Jeremy Robson Why the Veil Should be Repudiated* Yasmin Alibhai-Brown 2 0 1 6 *Extract from Refusing the Veil, 2014. Published with kind permission of Biteback V Publishing, London. O L U Continued on inside back cover M E T W E N Nottingham Law School T The Nottingham Trent University Y Burton Street F I V Nottingham E NG1 4BU England £30.00 Volume 25, 2016 d_Nott-law jnl25_cover_Nott-Law_cv 25/07/2016 13:18 Page 2 Continued from outside back cover Book Reviews E Brems (ed.) The Experiences of Face Veil Wearers in Europe and the Law Cambridge University Press, 2014 Amal Ali Jill Marshall Human Rights Law and Personal Identity Routledge, 2014 Tom Lewis CASE NOTES AND COMMENTARY Killing the Parasite in R v Jogee Catarina Sjolin-Knight Disputing the Indisputable: Genocide Denial and Freedom of Expression in Perinçek v Switzerland Luigi Daniele Innocent Dissemination: The Type of Knowledge Concerned in Shen, Solina Holly v SEEC Media Group Limited S.H. -

Jury Announced for the 27Th Annual Lionel Gelber Prize

Jury Announced for the 27th Annual Lionel Gelber Prize For Immediate Release: January 3, 2017 (Toronto and Washington): Sara Charney, Chair of the Lionel Gelber Prize and President of The Lionel Gelber Foundation, and Stephen Toope, Director of the Munk School of Global Affairs, are pleased to announce an outstanding jury for the 2017 Prize, as follows: John Stackhouse, Jury Chair (Toronto, Canada) is joined by 2016 Lionel Gelber Prize Winner and journalist Scott Shane (Maryland, USA), Professor Allison Stanger (Vermont, USA), Dr. Astrid Tuminez (Singapore), and Professor Antje Wiener (Hamburg, Germany) to form the 2017 Jury. “Created in memory of the Canadian scholar, diplomat and author Lionel Gelber, we are gratified that the Prize attracts such distinguished jurors, year after year,” said Ms Charney, niece of the late Lionel Gelber. Key Dates: Five books will be named to the jury’s shortlist on January 31. Podcast interviews with each of the shortlisted authors in conversation with Professor Robert Steiner will be presented in partnership with Focus Asset Management. The winner will be announced on February 28 and invited to speak at a free public event at the Munk School of Global Affairs on March 29, 2017. About the Prize: The Lionel Gelber Prize, a literary award for the world’s best non-fiction book in English on foreign affairs that seeks to deepen public debate on significant international issues, was founded in 1989 by Canadian diplomat Lionel Gelber. A cash prize of $15,000 is awarded to the winner. The award is presented annually by The Lionel Gelber Foundation, in partnership with Foreign Policy magazine and the Munk School of Global Affairs. -

I No. 14-35095 in the UNITED STATES

No. 14-35095 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT AMERICAN FREEDOM DEFENSE INITIATIVE; PAMELA GELLER; and ROBERT SPENCER Appellants, v. KING COUNTY Appellee, ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF WASHINGTON CASE NO. 2:13-cv-01804-RAJ (HON. RICHARD A. JONES) PROPOSED AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF OF THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION OF WASHINGTON VENKAT BALASUBRAMANI SARAH A. DUNNE Focal PLLC Legal Director 800 Fifth Avenue Suite 4100 LA ROND M. BAKER Seattle, WA 98104-3100 Staff Attorney Telephone: (206) 529-4827 ACLU of Washington Foundation 901 Fifth Avenue Suite 630 Seattle, WA 98164 Telephone: (206) 624-2184 i CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT Pursuant to FRAP 26.1, the American Civil Liberties Union of Washington certifies that it is a Washington non-profit corporation. It has no parent corporations, and no publicly held company owns 10 percent or more of its stock. ii STATEMENT OF COMPLIANCE WITH FED. R. APP. P. 29(C)(5) No party’s counsel authored this brief in whole or in part. No party or party’s counsel contributed money that was intended to fund preparing or submitting this brief. And no person other than the American Civil Liberties Union of Washington, its members, or its counsel contributed money that was intended to fund preparing or submitting this brief. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT .................................................... ii STATEMENT OF COMPLIANCE WITH FED. R. APP. P. 29(C)(5) ............ iii I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 1 II. FACTUAL BACKGROUND ........................................................................... 2 III. PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND ............................................................... 3 IV. ARGUMENT .................................................................................................. 4 A. Viewpoint Discrimination is Offensive to the First Amendment in Both Designated and Limited Public Forums. -

Penamerica Principles Oncampus Freespeech

of speech curtailed, there is not, as some accounts have PEN!AMERICA! suggested, a pervasive “crisis” for free speech on campus. Unfortunately, respect for divergent viewpoints has PRINCIPLES! not been a consistent hallmark of recent debates on ma!ers of diversity and inclusion on campus. Though ON!CAMPUS! sometimes overblown or oversimplified, there have been many instances where free speech has been suppressed FREE!SPEECH or chilled, a pa!ern that is at risk of escalating absent concerted action. In some cases, students and univer- sity leaders alike have resorted to contorted and trou- The State of Free Speech on Campus bling formulations in trying to reconcile the principles One of the most talked-about free speech issues in the of free inquiry, inclusivity, and respect for all. There are United States has li"le to do with the First Amendment, also particular areas where legitimate efforts to enable the legislature, or the courts. A set of related controversies full participation on campus have inhibited speech. The and concerns have roiled college and university campuses, discourse also reveals, in certain quarters, a worrisome dis- pi"ing student activists against administrators, faculty, and, missiveness of considerations of free speech as the retort almost as o#en, against other students. The clashes, cen- of the powerful or a diversion from what some consider tering on the use of language, the treatment of minorities to be more pressing issues. Alongside that is evidence and women, and the space for divergent ideas, have shone of a passive, tacit indifference to the risk that increased a spotlight on fundamental questions regarding the role sensitivity to differences and offense—what some call “po- and purpose of the university in American society. -

Obscenity, Miller,And the Future of Public Discourse on the Intemet John Tehranian University of Utah, S.J

Journal of Intellectual Property Law Volume 11 | Issue 1 Article 7 April 2016 Sanitizing Cyberspace: Obscenity, Miller,and the Future of Public Discourse on the Intemet John Tehranian University of Utah, S.J. Quinney College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/jipl Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation John Tehranian, Sanitizing Cyberspace: Obscenity, Miller,and the Future of Public Discourse on the Intemet, 11 J. Intell. Prop. L. 1 (2016). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/jipl/vol11/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Intellectual Property Law by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. Please share how you have benefited from this access For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tehranian: Sanitizing Cyberspace: Obscenity, Miller,and the Future of Public JOURNAL OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW VOLUME 11 FALL 2003 NUMBER 1 ARTICLES SANITIZING CYBERSPACE: OBSCENITY, MILLER, AND THE FUTURE OF PUBLIC DISCOURSE ON THE INTERNET John Tehranian* I. INTRODUCTION Upon hearing the obstreperous thump of a man incessantly pounding his bongo drums in the public park, writer Donald Barthelme once observed: "I hate bongo drums. I started to tell him to stop playing those goddamn bongo drums but then I said to myself, No, that's not right. You got to let him play his goddamn bongo drums if he feels like it, it's part of the misery of democracy, to which I subscribe."' To be sure, the misery of democracy dictates that we tolerate viewpoints other than our own, that we let people play the bongo drums, however begrudgingly. -

Haarscher, Guy Publicado

Perelman, the use of the “pseudo-argument” and human rights Autor(es): Haarscher, Guy Publicado por: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/32028 DOI: DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.14195/978-989-26-0498-5_17 Accessed : 24-Sep-2021 17:10:17 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. pombalina.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt RHETORIC AND ARGUMENTATION IN THE BEGINNING OF XXI AND ARGUMENTATION RHETORIC THE EDITOR THE BOOK Henrique Jales Ribeiro is Associate Professor at the Faculty This book is the edition of the Proceedings of the International of Letters of the University of Coimbra (Portugal), where, Colloquium “Rhetoric and Argumentation in the Beginning of the presently, he teaches Logic, Argumentation Theories, and a XXIst Century” which was held at the Faculty of Letters of the post graduate seminary on the Logic of the Sciences. -

Uncomfortable, but Educational: Freedom of Expression in UK Universities Contents

Uncomfortable, but educational: Freedom of expression in UK universities Contents 1. Executive Summary 4 2. Introduction 6 3. The road to legislation: a brief history 8 4. Legislation applicable to higher education institutions 9 5. Current concerns on UK campuses 12 6. Conclusion and recommendations 20 Appendix 1: Examples of best practice 21 Appendix 2: The legal landscape in the UK 22 This document was compiled with the support of Clifford Chance and Jonathan Price, Doughty Street Chambers. 2 Kanumbra / flickr Uncomfortable, but educational Uncomfortable, but educational Tom Parnell / flickr 3 Executive summary ree speech is vital to the free flow of thoughts and ideas. A freedom of expression organisation with an international remit, FNowhere is this perhaps more important than in universities, Index on Censorship seeks to highlight violations of freedom of which are crucibles for new thought and academic discovery, expression all over the world. Our approach to the principle of and whose remit is to encourage and foster critical thinking. freedom of expression is without political affiliation. In recent years, however, there has been a concerning rise in In Free Speech on Campus we look at the situation today on apparent attempts to shut down debates on certain subject areas UK campuses and in particular examine the existing legal and in universities in the UK and elsewhere. Speakers whose views other protections for free speech in universities. This comes in are deemed “offensive”, “harmful” or even “dangerous” have the wake of renewed government commitments to protect been barred from speaking at events, conferences on particular freedom of expression on campus. -

The Russian Draft Federal

MEMORANDUM on the Russian Draft Federal Law “On Combating the Rehabilitation of Nazism, Nazi Criminals or their Collaborators in the Newly Independent States Created on the Territory of Former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics” London September 2009 ARTICLE 19, Free Word Centre, 60 Farringdon Road, London EC1R 3GA United Kingdom Tel: +44 20 7324 2500. Fax: +44 20 7490 0566 [email protected] · http://www.article19.org TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................1 II. INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS ON FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION ........................................2 1. GUARANTEES OF FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION ...........................................................................................2 2. RESTRICTIONS ON FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION .........................................................................................3 3. FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND DEMOCRACY ..........................................................................................4 4. PROTECTION OF DEBATES ON HISTORICAL ISSUES ..................................................................................4 5. RESTRICTIONS ON DEBATES ON HISTORY ...............................................................................................5 III. ANALYSIS OF THE DRAFT LAW................................................................................................8 1. BACKGROUND OF THE DRAFT LAW...........................................................................................................8 -

5 Intermediary Censorship

5 Intermediary Censorship Ethan Zuckerman Introduction When academics, journalists, or Internet users discuss ‘‘Internet censorship,’’ they are usually referring to the inability of users in a given country to access a specific piece of online content. For instance, when Internet policymakers from around the world came to Tunisia for the 2005 World Summit on the Information Society, they discovered that the Tunisian government was blocking access to several sites, including Yezzi.org, an online freedom of speech campaign.1 This model of Internet filtering, where Internet service providers (ISPs) implement directives issued by government authorities and block connections to selected Web addresses, has been extensively documented by the OpenNet Initiative using in- country testing. Identifying potential cases of filtering by ISPs is likely to be easier in the future with the advent of tools like Herdict (www.herdict.org), which invite end users to be involved with in-country testing on a continuing basis. Given aggressive national filtering policies implemented in countries like Saudi Arabia, China, and Vietnam, state-sponsored ISP-level Web filtering has been an appro- priate locus for academic study. However, ISPs are only one possible choke point in a global Internet. As the Internet increases in popularity around the world, we are begin- ning to see evidence of Internet filtering at other points in the network. Of particular interest are online service providers (OSPs) that host social networking services, blogs, and Web sites. Because so many Internet users are dependent on OSPs to publish con- tent, censorship by these entities has the potential to be a powerful control on online speech. -

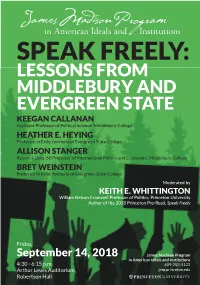

SPEAK FREELY: LESSONS from MIDDLEBURY and EVERGREEN STATE KEEGAN CALLANAN Assistant Professor of Politi Cal Science, Middlebury College HEATHER E

SPEAK FREELY: LESSONS FROM MIDDLEBURY AND EVERGREEN STATE KEEGAN CALLANAN Assistant Professor of Politi cal Science, Middlebury College HEATHER E. HEYING Professor in Exile, formerly of Evergreen State College ALLISON STANGER Russell J. Leng ‘60 Professor of International Politics and Economics, Middlebury College BRET WEINSTEIN Professor in Exile, formerly of Evergreen State College Moderated by KEITH E. WHITTINGTON William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Politi cs, Princeton University Author of the 2018 Princeton Pre-Read, Speak Freely Friday, September 14, 2018 James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions 4:30 - 6:15 p.m. 609-258-1122 Arthur Lewis Auditorium, jmp.princeton.edu Robertson Hall KEEGAN CALLANAN is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Middlebury College, where he has teaching responsibilities in the history of political philosophy and contemporary political theory. His primary research is in modern political thought, and he is the author of a book on the political philosophy of Montesquieu titled Montesquieu’s Liberalism and the Problem of Universal Politics (Cambridge University Press, 2018). His work has appeared in journals such as History of Political Thought and Political Research Quarterly. Prior to his appointment at Middlebury, he taught at the University of Virginia as a Post-doctoral Fellow in the Department of Politics. He was a 2017-18 Visiting Fellow in the James Madison Program. A graduate of Bowdoin College, he received his M.A. and Ph.D. from Duke University. HEATHER HEYING is a scientist and an educator. She was a professor of evolutionary biology at The Evergreen State College for 15 years, where she provided undergraduates an evolutionary toolkit with which to understand how to be critical, engaged citizens of the world, in part through exploring remote sites in the neotropics. -

Exploring Free Speech on College Campuses Hearing

S. HRG. 115–660 EXPLORING FREE SPEECH ON COLLEGE CAMPUSES HEARING OF THE COMMITTEE ON HEALTH, EDUCATION, LABOR, AND PENSIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON EXAMINING FREE SPEECH ON COLLEGE CAMPUSES OCTOBER 26, 2017 Printed for the use of the Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 27–450 PDF WASHINGTON : 2019 COMMITTEE ON HEALTH, EDUCATION, LABOR, AND PENSIONS LAMAR ALEXANDER, Tennessee, Chairman MICHAEL B. ENZI, Wyoming PATTY MURRAY, Washington RICHARD BURR, North Carolina BERNARD SANDERS (I), Vermont JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia ROBERT P. CASEY, JR., Pennsylvania RAND PAUL, Kentucky AL FRANKEN, Minnesota SUSAN M. COLLINS, Maine MICHAEL F. BENNET, Colorado BILL CASSIDY, M.D., Louisiana SHELDON WHITEHOUSE, Rhode Island TODD YOUNG, Indiana TAMMY BALDWIN, Wisconsin ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah CHRISTOPHER S. MURPHY, Connecticut PAT ROBERTS, Kansas ELIZABETH WARREN, Massachusetts LISA MURKOWSKI, Alaska TIM KAINE, Virginia TIM SCOTT, South Carolina MAGGIE WOOD HASSAN, New Hampshire DAVID P. CLEARY, Republican Staff Director LINDSEY WARD SEIDMAN, Republican Deputy Staff Director EVAN SCHATZ, Democratic Staff Director JOHN RIGHTER, Democratic Deputy Staff Director (II) CONTENTS STATEMENTS THURSDAY, OCTOBER 26, 2017 Page COMMITTEE MEMBERS Alexander, Hon. Lamar, Chairman, Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, opening statement ....................................................................... 1 Murray, Hon. Patty, a U.S. Senator from the State of Washington ................... 4 Young, Hon. Todd, a U.S. Senator from the State of Indiana ............................. 43 Bennet, Hon. Michael F., a U.S. Senator from the State of Colorado ................. 45 Isakson, Hon. Johnny, a U.S. Senator from the State of Georgia ......................