Report Eport a Eport April 13, 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1990 GENERAL ELECTION UNITED STATES SENATOR Democrat Baron P. Hill 28,655 Republican Dan Coats 23,582 SECRETARY of STATE Democrat Joseph H

1990 GENERAL ELECTION UNITED STATES SENATOR democrat Baron P. Hill 28,655 republican Dan Coats 23,582 SECRETARY OF STATE democrat Joseph H. Hogsett 27,842 republican William H. Hudnut III 23,973 AUDITOR OF STATE democrat Ann A. Whaley 25,695 republican Ann G. DeVore 23,193 TREASURER OF STATE democrat Thomas L. New 22,590 republican Marjorie H. O'Laughlin 27,586 CLERK OF SUPREME & APPELLATE COURTS democrat Dwayne M. Brown 27,409 republican Daniel Rock Heiser 20,343 CONGRESS 8TH DISTRICT democrat Frank McCloskey 27,856 republican Richard E. Mourdock 24,892 STATE SENATOR DISTRICT 49 democrat Joseph F. O'Day 13,691 republican Linda L. Orth 7,746 STATE REPRESENTATIVE DISTRICT 75 democrat Dennis T. Avery 15,298 democrat Mark Alan sunderman 9,545 republican Vaneta G. Becker 20,226 republican Joseph H. Harrison, Jr. 14,079 STATE REPRESENTATIVE DISTRICT 76 democrat Larry E. Lutz 6,235 republican Jan Gallo 3,248 STATE REPRESENTATIVE DISTRICT 77 democrat J. Jeff Hays 10,093 PROSECUTING ATTORNEY democrat Stanley M. Levco 31,947 republican Glen A. Deig 19,795 COUNTY AUDITOR democrat Sam Humphrey 28,171 republican Genna A. Lloyd 23,514 COUNTY SHERIFF democrat Ray Hamner 26,954 republican Joe Rhodes 25,711 COUNTY ASSESSOR democrat James L. Angermeier 27,775 republican Ed Witte 23,494 COMMISSIONER DISTRICT TWO democrat Mark R. Owen 25,245 republican Don L. Hunter 26,391 COUNTY COUNCIL DISTRICT ONE democrat Robert Lutz 5,108 republican James B. Raben 5,706 COUNTY COUNCIL DISTRICT TWO democrat no candidate republican Curt Wortman 10,479 COUNTY COUNCIL DISTRICT THREE democrat Bill Palmer Taylor 4,482 republican Michael J. -

September 11 & 12 . 2008

n e w y o r k c i t y s e p t e m b e r 11 & 12 . 2008 ServiceNation is a campaign for a new America; an America where citizens come together and take responsibility for the nation’s future. ServiceNation unites leaders from every sector of American society with hundreds of thousands of citizens in a national effort to call on the next President and Congress, leaders from all sectors, and our fellow Americans to create a new era of service and civic engagement in America, an era in which all Americans work together to try and solve our greatest and most persistent societal challenges. The ServiceNation Summit brings together 600 leaders of all ages and from every sector of American life—from universities and foundations, to businesses and government—to celebrate the power and potential of service, and to lay out a bold agenda for addressing society’s challenges through expanded opportunities for community and national service. 11:00-2:00 pm 9/11 DAY OF SERVICE Organized by myGoodDeed l o c a t i o n PS 124, 40 Division Street SEPTEMBER 11.2008 4:00-6:00 pm REGIstRATION l o c a t i o n Columbia University 9/11 DAY OF SERVICE 6:00-7:00 pm OUR ROLE, OUR VOICE, OUR SERVICE PRESIDENTIAL FORUM& 101 Young Leaders Building a Nation of Service l o c a t i o n Columbia University Usher Raymond, IV • RECORDING ARTIST, suMMIT YOUTH CHAIR 7:00-8:00 pm PRESIDEntIAL FORUM ON SERVICE Opening Program l o c a t i o n Columbia University Bill Novelli • CEO, AARP Laysha Ward • PRESIDENT, COMMUNITY RELATIONS AND TARGET FOUNDATION Lee Bollinger • PRESIDENT, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY Governor David A. -

If It's Broke, Fix It: Restoring Federal Government Ethics and Rule Of

If it’s Broke, Fix it Restoring Federal Government Ethics and Rule of Law Edited by Norman Eisen The editor and authors of this report are deeply grateful to several indi- viduals who were indispensable in its research and production. Colby Galliher is a Project and Research Assistant in the Governance Studies program of the Brookings Institution. Maya Gros and Kate Tandberg both worked as Interns in the Governance Studies program at Brookings. All three of them conducted essential fact-checking and proofreading of the text, standardized the citations, and managed the report’s production by coordinating with the authors and editor. IF IT’S BROKE, FIX IT 1 Table of Contents Editor’s Note: A New Day Dawns ................................................................................. 3 By Norman Eisen Introduction ........................................................................................................ 7 President Trump’s Profiteering .................................................................................. 10 By Virginia Canter Conflicts of Interest ............................................................................................... 12 By Walter Shaub Mandatory Divestitures ...................................................................................... 12 Blind-Managed Accounts .................................................................................... 12 Notification of Divestitures .................................................................................. 13 Discretionary Trusts -

Sagamore in the Nation's Service

SAGAMORE IN THE NATION’S SERVICE 2006-2009 Deborah Daniels served as president of Sagamore lowed by a half dozen Sagamore board members Institute from 2006-08 and her career epitomizes the eventually serving in the Bush administration. think tank’s vision for local impact and national influ- The Honorable Daniel R. Coats served as U.S. Am- ence. As the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District bassador to Germany from 2001-2005. He currently of Indiana during the President George H.W. Bush represents the people of Indiana as a member of the administration, Daniels helped pioneer the Weed and U.S. Senate. Seed program in Indianapolis integrating law enforce- James T. Morris served as the Executive Director of ment, community policing, violence prevention and the United Nations World Food Program, the world’s neighborhood restoration efforts. The success led to largest food aid organization, from 2002-07. He is her being named the first Director of the Executive presently President of Pacers Sports and Entertain- Office of Weed and Seed at the U.S. Department of ment. Justice in 1992-93. Dr. Leslie Lenkowsky was chief executive officer of Daniels returned to Indianapolis in the mid-1990s the Corporation for National and Community Service to lead the Greater Indianapolis Progress Committee from 2001-04 serving under the leadership of CNCS which bolstered economic development and neigh- chair Stephen Goldsmith. Lenkowsky is now a faculty borhood revitalization during the national pace-set- member at Indiana University. ting administration of Indianapolis mayor Stephen Dr. Carol D’Amico served as Assistant Secretary Goldsmith. -

Transforming Government Through Privatization

20th Anniversary Edition Annual Privatization Report 2006 Transforming Government Through Privatization Reflections from Pioneers in Government Reform Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher Governor Mitch Daniels Governor Mark Sanford Robert W. Poole, Jr. Reason Foundation Reason Foundation’s mission is to advance a free society by developing, apply- ing, and promoting libertarian principles, including individual liberty, free markets, and the rule of law. We use journalism and public policy research to influence the frameworks and actions of policymakers, journalists, and opin- ion leaders. Reason Foundation’s nonpartisan public policy research promotes choice, competition, and a dynamic market economy as the foundation for human dignity and prog- ress. Reason produces rigorous, peer-reviewed research and directly engages the policy pro- cess, seeking strategies that emphasize cooperation, flexibility, local knowledge, and results. Through practical and innovative approaches to complex problems, Reason seeks to change the way people think about issues, and promote policies that allow and encourage individuals and voluntary institutions to flourish. Reason Foundation is a tax-exempt research and education organization as defined under IRS code 501(c)(3). Reason Foundation is supported by voluntary contributions from individuals, foundations, and corporations. The views expressed in these essays are those of the individual author, not necessarily those of Reason Foundation or its trustees. Copyright © 2006 Reason Foundation. Photos used in this publication are copyright © 1996 Photodisc, Inc. All rights reserved. Authors Editor the Association of Private Correctional & Treatment Organizations • Leonard C. Gilroy • Chris Edwards is the director of Tax Principal Authors Policy Studies at the Cato Institute • Ted Balaker • William D. Eggers is the global director • Shikha Dalmia for Deloitte Research—Public Sector • Leonard C. -

Jury Announced for the 27Th Annual Lionel Gelber Prize

Jury Announced for the 27th Annual Lionel Gelber Prize For Immediate Release: January 3, 2017 (Toronto and Washington): Sara Charney, Chair of the Lionel Gelber Prize and President of The Lionel Gelber Foundation, and Stephen Toope, Director of the Munk School of Global Affairs, are pleased to announce an outstanding jury for the 2017 Prize, as follows: John Stackhouse, Jury Chair (Toronto, Canada) is joined by 2016 Lionel Gelber Prize Winner and journalist Scott Shane (Maryland, USA), Professor Allison Stanger (Vermont, USA), Dr. Astrid Tuminez (Singapore), and Professor Antje Wiener (Hamburg, Germany) to form the 2017 Jury. “Created in memory of the Canadian scholar, diplomat and author Lionel Gelber, we are gratified that the Prize attracts such distinguished jurors, year after year,” said Ms Charney, niece of the late Lionel Gelber. Key Dates: Five books will be named to the jury’s shortlist on January 31. Podcast interviews with each of the shortlisted authors in conversation with Professor Robert Steiner will be presented in partnership with Focus Asset Management. The winner will be announced on February 28 and invited to speak at a free public event at the Munk School of Global Affairs on March 29, 2017. About the Prize: The Lionel Gelber Prize, a literary award for the world’s best non-fiction book in English on foreign affairs that seeks to deepen public debate on significant international issues, was founded in 1989 by Canadian diplomat Lionel Gelber. A cash prize of $15,000 is awarded to the winner. The award is presented annually by The Lionel Gelber Foundation, in partnership with Foreign Policy magazine and the Munk School of Global Affairs. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ANNU AL REPOR T 2 0 0 7 P AR TNER Ship F OR PU B L Ic S ER Vic E

ANNUAL REPORT 2007 REPORT ANNUAL partnerSHIP FOR PUBLIC SERVICE ANNUAL REPORT 2007 nw 20005 fax dc east 1100 New York Avenue Avenue York 1100 New Suite 1090 Suite Washington 202 775 9111 202 775 8885 ourpublicservice.org NASA’s Hubble TABLE OF CONTENTS Telescope 03 GOVERNMENT’S EVERYDAY IMPACT INDEX has recorded images from 04 LEttER FROM THE CHAIRMAN AND THE PRESIDENT over 12 billion 05 OUR STRATEGY FOR CHANGE 145 million GPS technology The National The U.S. light years away 07 INSPIRE phone was developed Park Service Geological 10 TRANSFORM numbers are by the U.S. maintains Survey 15 PARTNERSHIP’S IMPAct INDEX enrolled in the Department of 170 million Nearly 750,000 25,749 miles monitors 16 2007 SERVICE TO AMERICA MEDALS 20 percent of Federal Trade Defense acres of people visit a of trail for park seismic activity Commission’s 21 SUSTAINING OUR MISSION U.S. electricity wilderness are national park visitors worldwide for is generated “Do Not Call” protected by every day an estimated 27 BOARD OF DIREctORS / by federally Registry the Department 1.4 million ADVISORY BOARD OF GOVERNORS regulated of the Interior earthquakes 31 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS nuclear power each year 34 pARTNERSHIP TEAMS plants Americans Photo credits: Front and back cover, Flickr.com: -cr, Alby Space, Andre di Lucca, angela7dreams, babasteve, Beau M., purchased The U.S. Department bubbabyte, Byron and Tamara, caitie.elle, Celina Ortelli, Cestovatel, chalkdog, challiyan, Cyril Plapied, darkmatter, more than 160,000 public eliazar, GaijinSeb, graphia, gullevek, Hamed Masoumi, -

Link to PDF Version

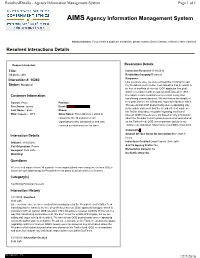

ResolvedDetails - Agency Information Management System Page 1 of 1 AIMS Agency Information Management System Announcement: If you create a duplicate interaction, please contact Gwen Cannon-Jenkins to have it deleted Resolved Interactions Details Reopen Interaction Resolution Details Title: Interaction Resolved:11/30/2016 34 press calls Resolution Category:Resolved Interaction #: 10260 Response: Like everyone else, we were excited this morning to read Status: Resolved the President-elect’s twitter feed indicating that he wants to be free of conflicts of interest. OGE applauds that goal, which is consistent with an opinion OGE issued in 1983. Customer Information Divestiture resolves conflicts of interest in a way that transferring control does not. We don’t know the details of Source: Press Position: their plan, but we are willing and eager to help them with it. The tweets that OGE posted today were responding only First Name: James Email: (b)(6) ' to the public statement that the President-elect made on Last Name: Lipton Phone: his Twitter feed about his plans regarding conflicts of Title: Reporter - NYT Other Notes: This contact is a stand-in interest. OGE’s tweets were not based on any information contact for the 34 separate news about the President-elect’s plans beyond what was shared organizations who contacted us and who on his Twitter feed. OGE is non-partisan and does not received our statement on the issue. endorse any individual. https://twitter.com/OfficeGovEthics Complexity( Amount Of Time Spent On Interaction:More than 8 Interaction Details hours Initiated: 11/30/2016 Individuals Credited:Leigh Francis, Seth Jaffe Call Origination: Phone Add To Agency Profile: No Assigned: Seth Jaffe Memorialize Content: No Watching: Do Not Destroy: No Questions We received inquires from 34 separate news organizations concerning tweets from OGE's twitter account addressing the President-elect's plans to avoid conflicts of interest. -

Howey Political Report Is Published 40 Times a Year by Media

Special Edition: 1996 Indiana Democratic Convention Wednesday, June 5, 1996 • Volume 2, Number 34 Page 1of8 ••••• O'Bannon blisters ....•• • • • ·-·--·• •••• •• •• Goldsmith on freeze THE -- Property tax becomes first campaign battle INDIANAPOLIS - Mayor Stephen Goldsmith launched the first shot in the Indiana gubernatorial race with his call for a "hard HOWEY freeze" in property taxes that he said would result in a $4 billion sav ings for taxpayers. Goldsmith told the Indiana Bankers Association Wednesday POLITICAL morning that such a move would "immediately change the dynamic of property tax relief" and create economic growth. Hours later, in a "rapid response" reminiscent of Bill Clinton's 1992 campaign, Lt. Gov. Frank O'Bannon dismissed the proposal as a REPORT "shell game?' "Ifyou just freeze the rate and say simply that's going to The Weekly Briefing On Indiana Politics freeze taxes or cut taxes ... and your assessment goes up, you're going to pay more taxes;' O'Bannon told a room packed with the news The Howey Political Report is published 40 times a year by media. "I'm saying over the next four years if you freeze the tax rate NewsLink, Inc. The Howey Political Report is an independent, in the reassessment on fair market value, the homeowner is going to non-partisan newsletter analyzing the political process in Indiana. It neither endorses candidates nor advocates positions take it on the chin as well as the farmer. They're going to pay more of public policy. taxes. "That's the story today and you'll write 'Goldsmith cuts prop Brian A. Howey editor and publisher erty taxes' and all he's doing is freezing the rate. -

Ending Dependency: Lessons from Welfare Reform in The

Ending Dependency Ending Dependency Lessons from Welfare Reform in the USA Douglas J. Besharov Peter Germanis Jay Hein Donald K. Jonas Amy L. Sherman with an Introduction by Alan Deacon CIVITAS: Institute for the Study of Civil Society London First published 2001 © The Institute for the Study of Civil Society 2001 email: [email protected] All rights reserved ISBN 1-903 386-12-8 Typeset by CIVITAS in New Century Schoolbook Printed in Great Britain by Contents Page The Authors vi Introduction The Realities of Welfare Reform: Some Home Truths from the USA? Alan Deacon 1 The Florida Devolution Model: Lessons from the WAGES Welfare Reform Experiment Donald K. Jonas 8 Milwaukee After W-2 Amy L. Sherman 24 Welfare Reform: Four Years Later Douglas J. Besharov and Peter Germanis 43 New York Reformed Jay Hein 59 Notes 75 The Authors Douglas J. Besharov is the Joseph J. and Violet Jacobs Scholar in Social Welfare Studies at the American Enter- prise Institute. He is also a professor at the University of Maryland’s School of Public Affairs and director of its Welfare Reform Academy. He is the author or editor of several books, including Recognizing Child Abuse: A Guide for the Concerned, 1990; Enhancing Early Childhood Programs: Burdens and Opportunities, 1996; and America’s Disconnected Youth, 1999. Alan Deacon is Professor of Social Policy and a member of the ESRC Group on Care, Values and the Future of Welfare at the University of Leeds. He has written widely on the debate about welfare reform in Britain and the United States, most recently in Political Quarterly, 1998; Journal of Social Policy, 1999 and Policy and Politics, 2000. -

INDIANA's 1988 GUBERNATORIAL RESIDENCY CHALLENGE Joseph

INDIANA’S 1988 GUBERNATORIAL RESIDENCY CHALLENGE Joseph Hadden Hogsett Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of History Indiana University June 2007 Accepted by the Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Robert G. Barrows, Ph.D., Chair Elizabeth Brand Monroe, Ph.D. Master’s Thesis Committee William A. Blomquist, Ph.D. ii Dedicated to the memory of my colleague and friend, Jon D. Krahulik iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I take this opportunity to thank the people who helped make this paper possible. Dr. Robert G. Barrows served as my seminar professor, my mentor and the Chair of this thesis committee. Many other graduate students have acknowledged his sound advice, his guidance, his editing and his sense of humor. All of those also apply here. In my case, however, above all, I owe him a debt of gratitude for patience. This paper began as a concept in his seminar in the spring of 2002, but was not finished for five years. Even if Dr. Barrows had known then how flawed and distracted the author would prove to be, I am convinced he still would have agreed to chair the project. His patience is a gift. I also acknowledge the advice offered unconditionally by the committee’s other members, Dr. Elizabeth Brand Monroe and Dr. William A. Blomquist. Though they, like Dr. Barrows, possessed sufficient probable cause to notify authorities of a “missing person”, both exercised incredible restraint and, in so doing, no doubt violated some antiquainted canon of academic protocol. -

Mid-America Intergovernmental Audit Forum (Mamiaf)

Gene L. Dodaro Comptroller General of the United States Gene L. Dodaro became the eighth Comptroller General of the United States and head of the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) on December 22, 2010, when he was confirmed by the United States Senate. He was nominated by President Obama in September of 2010 from a list of candidates selected by a bipartisan, bicameral congressional commission. He had been serving as Acting Comptroller General since March of 2008. Mr. Dodaro has testified before Congress dozens of times on important national issues, including the nation's long term fiscal outlook, efforts to reduce and eliminate overlap and duplication across the federal government and GAO's "High Risk List" that focuses on specific challenges—from reducing improper payments under Medicare and Medicaid to improving the Pentagon’s business practices. In addition Mr. Dodaro has led efforts to fulfill GAO’s new audit responsibilities under the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. As Comptroller General, Mr. Dodaro helps oversee the development and issuance of hundreds of reports and testimonies each year to various committees and individual Members of Congress. These and other GAO products have led to hearings and legislation, billions of dollars in taxpayer savings, and improvements to a wide range of government programs and services. Ron Elving Senior Washington Editor National Public Radio (NPR) Ron Elving is the NPR News' Senior Washington Editor directing coverage of the nation's capital and national politics and providing on-air political analysis for many NPR programs. Elving can regularly be heard on Talk of the Nation providing analysis of the latest in politics.