Encounters with Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grapheme-To-Lexeme Feedback in the Spelling System: Evidence from a Dysgraphic Patient

COGNITIVE NEUROPSYCHOLOGY, 2006, 23 (2), 278–307 Grapheme-to-lexeme feedback in the spelling system: Evidence from a dysgraphic patient Michael McCloskey Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, USA Paul Macaruso Community College of Rhode Island, Warwick, and Haskins Laboratories, New Haven, USA Brenda Rapp Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, USA This article presents an argument for grapheme-to-lexeme feedback in the cognitive spelling system, based on the impaired spelling performance of dysgraphic patient CM. The argument relates two features of CM’s spelling. First, letters from prior spelling responses intrude into sub- sequent responses at rates far greater than expected by chance. This letter persistence effect arises at a level of abstract grapheme representations, and apparently results from abnormal persistence of activation. Second, CM makes many formal lexical errors (e.g., carpet ! compute). Analyses revealed that a large proportion of these errors are “true” lexical errors originating in lexical selec- tion, rather than “chance” lexical errors that happen by chance to take the form of words. Additional analyses demonstrated that CM’s true lexical errors exhibit the letter persistence effect. We argue that this finding can be understood only within a functional architecture in which activation from the grapheme level feeds back to the lexeme level, thereby influencing lexical selection. INTRODUCTION a brain-damaged patient with an acquired spelling deficit, arguing from his error pattern that Like other forms of language processing, written the cognitive system for written word produc- word production implicates multiple levels of tion includes feedback connections from gra- representation, including semantic, orthographic pheme representations to orthographic lexeme lexeme, grapheme, and allograph levels. -

Notes on the Development of the Linguistic Society of America 1924 To

NOTES ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE LINGUISTIC SOCIETY OF AMERICA 1924 TO 1950 MARTIN JOOS for JENNIE MAE JOOS FORE\\ORO It is important for the reader of this document to know how it came to be written and what function it is intended to serve. In the early 1970s, when the Executive Committee and the Committee on Pub1ications of the linguistic Society of America v.ere planning for the observance of its Golden Anniversary, they decided to sponsor the preparation of a history of the Society's first fifty years, to be published as part of the celebration. The task was entrusted to the three living Secretaries, J M. Cowan{who had served from 1940 to 1950), Archibald A. Hill {1951-1969), and Thomas A. Sebeok {1970-1973). Each was asked to survey the period of his tenure; in addition, Cowan,who had learned the craft of the office from the Society's first Secretary, Roland G. Kent {deceased 1952),was to cover Kent's period of service. At the time, CO'flal'\was just embarking on a new career. He therefore asked his close friend Martin Joos to take on his share of the task, and to that end gave Joos all his files. Joos then did the bulk of the research and writing, but the~ conferred repeatedly, Cowansupplying information to which Joos v.t>uldnot otherwise have had access. Joos and HiU completed their assignments in time for the planned publication, but Sebeok, burdened with other responsibilities, was unable to do so. Since the Society did not wish to bring out an incomplete history, the project was suspended. -

ON SOME CATEGORIES for DESCRIBING the SEMOLEXEMIC STRUCTURE by Yoshihiko Ikegami

ON SOME CATEGORIES FOR DESCRIBING THE SEMOLEXEMIC STRUCTURE by Yoshihiko Ikegami 1. A lexeme is the minimum unit that carries meaning. Thus a lexeme can be a "word" as well as an affix (i.e., something smaller than a word) or an idiom (i.e,, something larger than a word). 2. A sememe is a unit of meaning that can be realized as a single lexeme. It is defined as a structure constituted by those features having distinctive functions (i.e., serving to distinguish the sememe in question from other semernes that contrast with it).' A question that arises at this point is whether or not one lexeme always corresponds to just one serneme and no more. Three theoretical positions are foreseeable: (I) one which holds that one lexeme always corresponds to just one sememe and no more, (2) one which holds that one lexeme corresponds to an indefinitely large number of sememes, and (3) one which holds that one lexeme corresponds to a certain limited number of sememes. These three positions wiIl be referred to as (1) the "Grundbedeutung" theory, (2) the "use" theory, and (3) the "polysemy" theory, respectively. The Grundbedeutung theory, however attractive in itself, is to be rejected as unrealistic. Suppose a preliminary analysis has revealed that a lexeme seems to be used sometimes in an "abstract" sense and sometimes in a "concrete" sense. In order to posit a Grundbedeutung under such circumstances, it is to be assumed that there is a still higher level at which "abstract" and "concrete" are neutralized-this is certainly a theoretical possibility, but it seems highly unlikely and unrealistic from a psychological point of view. -

Similarities and Differences Between Simultaneous and Successive Bilingual Children: Acquisition of Japanese Morphology

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature E-ISSN: 2200-3452 & P-ISSN: 2200-3592 www.ijalel.aiac.org.au Similarities and Differences between Simultaneous and Successive Bilingual Children: Acquisition of Japanese Morphology Yuki Itani-Adams1, Junko Iwasaki2, Satomi Kawaguchi3* 1ANU College of Asia & the Pacific, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, 2601, Australia 2School of Arts and Humanities, Edith Cowan University, 2 Bradford Street, Mt Lawley WA 6050, Australia 3School of Humanities and Communication Arts, Western Sydney University, Bullecourt Ave, Milperra NSW 2214, Australia Corresponding Author: Satomi Kawaguchi , E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history This paper compares the acquisition of Japanese morphology of two bilingual children who had Received: June 14, 2017 different types of exposure to Japanese language in Australia: a simultaneous bilingual child Accepted: August 14, 2017 who had exposure to both Japanese and English from birth, and a successive bilingual child Published: December 01, 2017 who did not have regular exposure to Japanese until he was six years and three months old. The comparison is carried out using Processability Theory (PT) (Pienemann 1998, 2005) as a Volume: 6 Issue: 7 common framework, and the corpus for this study consists of the naturally spoken production Special Issue on Language & Literature of these two Australian children. The results show that both children went through the same Advance access: September 2017 developmental path in their acquisition of the Japanese morphological structures, indicating that the same processing mechanisms are at work for both types of language acquisition. However, Conflicts of interest: None the results indicate that there are some differences between the two children, including the rate Funding: None of acquisition, and the kinds of verbal morphemes acquired. -

1. Introduction

A fox knows many things but a hedgehog one big thing Mark Aronoff Stony Brook University 1. Introduction Isaiah Berlin’s little book, The Hedgehog and the Fox (1953), takes its title from a line by the Greek poet Archilochus: πόλλ᾽ οἶδ᾽ ἀλωπηξ ἀλλ᾽ ἐχῖνος ἓν μέγα ‘many [things] knows [a] fox but [a] hedgehog one big [thing]’. Since it is impossible to do justice in a paraphrase to Berlin’s prose, I will quote the relevant passage in full: [T]aken figuratively, the words can be made to yield a sense in which they mark one of the deepest differences which divide writers and thinkers, and, it may be, human beings in general. For there exists a great chasm between those, on one side, who relate everything to a single central vision, one system less or more coherent or articulate, in terms of which they understand, think, and feel—a single, universal, organizing principle in terms of which alone all that they are and say has significance—and, on the other side, those who pursue many ends, often unrelated and even contradictory, connected, if at all, only in some de facto way, for some psychological or physiological cause, related by no moral or aesthetic principle; these last lead lives, perform acts, and entertain ideas that are centrifugal rather than centripetal, their thought is scattered or diffused, moving on many levels, seizing upon the essence of a vast variety of experiences and objects for what they are in themselves, without, consciously or unconsciously, seeking to fit them into, or exclude them from, any one unchanging, all-embracing, sometimes self-contradictory and incomplete, at times fanatical, unitary vision. -

Part 1: Introduction to The

PREVIEW OF THE IPA HANDBOOK Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet PARTI Introduction to the IPA 1. What is the International Phonetic Alphabet? The aim of the International Phonetic Association is to promote the scientific study of phonetics and the various practical applications of that science. For both these it is necessary to have a consistent way of representing the sounds of language in written form. From its foundation in 1886 the Association has been concerned to develop a system of notation which would be convenient to use, but comprehensive enough to cope with the wide variety of sounds found in the languages of the world; and to encourage the use of thjs notation as widely as possible among those concerned with language. The system is generally known as the International Phonetic Alphabet. Both the Association and its Alphabet are widely referred to by the abbreviation IPA, but here 'IPA' will be used only for the Alphabet. The IPA is based on the Roman alphabet, which has the advantage of being widely familiar, but also includes letters and additional symbols from a variety of other sources. These additions are necessary because the variety of sounds in languages is much greater than the number of letters in the Roman alphabet. The use of sequences of phonetic symbols to represent speech is known as transcription. The IPA can be used for many different purposes. For instance, it can be used as a way to show pronunciation in a dictionary, to record a language in linguistic fieldwork, to form the basis of a writing system for a language, or to annotate acoustic and other displays in the analysis of speech. -

Whole Language Instruction Vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students

Whole Language Instruction vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students Krissy Maddox Jay Feng Presentation at Georgia Educational Research Association Annual Conference, October 18, 2013. Savannah, Georgia 1 Abstract The purpose of this study is to investigate the efficacy of whole language instruction versus phonics instruction for improving reading fluency and spelling accuracy. The participants were the first grade students in the researcher’s general education classroom of a non-Title I school. Stratified sampling was used to randomly divide twenty-two participants into two instructional groups. One group was instructed using whole language principles, where the children only read words in the context of a story, without any phonics instruction. The other group was instructed using explicit phonics instruction, without a story or any contextual influence. After four weeks of treatment, results indicate that there were no statistical differences between the two literacy approaches in the effect on students’ reading fluency or spelling accuracy; however, there were notable changes in the post test results that are worth further investigation. In reading fluency, both groups improved, but the phonics group made greater gains. In spelling accuracy, the phonics group showed slight growth, while the whole language scores decreased. Overall, the phonics group demonstrated greater growth in both reading fluency and spelling accuracy. It is recommended that a literacy approach should combine phonics and whole language into one curriculum, but place greater emphasis on phonics development. 2 Introduction Literacy is the fundamental cornerstone of a student’s academic success. Without the skill of reading, children will almost certainly have limited academic, economic, social, and even emotional success in school and in later life (Pikulski, 2002). -

Unit 2 Structures Handout.Pdf

2. The definition of a language as a structure of structures 2.1. Phonetics and phonology Relevance for studying language in its natural or primary medium: oral sounds rather than written symbols. Phonic medium: the range of sounds produced by the speech organs insofar as the play a role in language Speech sounds: Individual sounds within that range Phonetics is the study of the phonic medium: The study of the production, transmission, and reception of human sound-making used in speech. e.g. classification of sounds as voiced vs voiceless: /b/ vs /p/ Phonology is the study of the phonic medium not in itself but in relation with language. e.g. application of voice to the explanation of differences within the system of language: housen vs housev usen vs usev 2.1.1. Phonetics It is usually divided into three branches which study the phonic medium from three points of view: Articulatory phonetics: speech sounds according to the way in which they are produced by the speech organs. Acoustic phonetics: speech sounds according to the physical properties of their sound-waves. Auditory phonetics: speech sounds according to their perception and identification. Articulatory phonetics has the longest tradition, and its progress in the 19th century contributed a standardize and internationally accepted system of phonetic transcription: the origins of the International Phonetic Alphabet used today and relying on sound symbols and diacritics. It studies production in relation with the vocal tract, i.e., organs such as: lungs trachea or windpipe, containing: larynx vocal folds glottis pharyngeal cavity nose mouth, containing fixed organs: teeth and teeth ridge hard palate pharyngeal wall mobile organs: lips tongue soft palate jaw According to their function and participation, sounds may take several features: Voice: voiced vs voiceless sounds, according to the participation of the vocal folds e.g. -

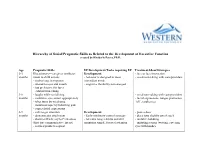

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills As Related to the Development of Executive Function Created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills as Related to the Development of Executive Function created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D. Age Pragmatic Skills EF Development/Tasks requiring EF Treatment Ideas/Strategies 0-3 Illocutionary—caregiver attributes Development: - face to face interaction months intent to child actions - behavior is designed to meet - vocal-turn-taking with care-providers - smiles/coos in response immediate needs - attends to eyes and mouth - cognitive flexibility not emerged - has preference for faces - exhibits turn-taking 3-6 - laughs while socializing - vocal turn-taking with care-providers months - maintains eye contact appropriately - facial expressions: tongue protrusion, - takes turns by vocalizing “oh”, raspberries. - maintains topic by following gaze - copies facial expressions 6-9 - calls to get attention Development: - peek-a-boo months - demonstrates attachment - Early inhibitory control emerges - place toys slightly out of reach - shows self/acts coy to Peek-a-boo - tolerates longer delays and still - imitative babbling (first true communicative intent) maintains simple, focused attention - imitating actions (waving, covering - reaches/points to request eyes with hands). 9-12 - begins directing others Development: - singing/finger plays/nursery rhymes months - participates in verbal routines - Early inhibitory control emerges - routines (so big! where is baby?), - repeats actions that are laughed at - tolerates longer delays and still peek-a-boo, patta-cake, this little piggy - tries to restart play maintain simple, -

Linguistic Scaffolds for Writing Effective Language Objectives

Linguistic Scaffolds for Writing Effective Language Objectives An effectively written language objective: • Stems form the linguistic demands of a standards-based lesson task • Focuses on high-leverage language that will serve students in other contexts • Uses active verbs to name functions/purposes for using language in a specific student task • Specifies target language necessary to complete the task • Emphasizes development of expressive language skills, speaking and writing, without neglecting listening and reading Sample language objectives: Students will articulate main idea and details using target vocabulary: topic, main idea, detail. Students will describe a character’s emotions using precise adjectives. Students will revise a paragraph using correct present tense and conditional verbs. Students will report a group consensus using past tense citation verbs: determined, concluded. Students will use present tense persuasive verbs to defend a position: maintain, contend. Language Objective Frames: Students will (function: active verb phrase) using (language target) . Students will use (language target) to (function: active verb phrase) . Active Verb Bank to Name Functions for Expressive Language Tasks articulate defend express narrate share ask define identify predict state compose describe justify react to summarize compare discuss label read rephrase contrast elaborate list recite revise debate explain name respond write Language objectives are most effectively communicated with verb phrases such as the following: Students will point out similarities between… Students will express agreement… Students will articulate events in sequence… Students will state opinions about…. Sample Noun Phrases Specifying Language Targets academic vocabulary complete sentences subject verb agreement precise adjectives complex sentences personal pronouns citation verbs clarifying questions past-tense verbs noun phrases prepositional phrases gerunds (verb + ing) 2011 Kate Kinsella, Ed.D. -

Linguistics As a Resouvce in Language Planning. 16P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 095 698 FL 005 720 AUTHOR Garvin, Paul L. TITLE' Linguistics as a Resouvce in Language Planning. PUB DATE Jun 73 NOTE 16p.; PaFPr presented at the Symposium on Sociolinguistics and Language Planning (Mexico City, Mexico, June-July, 1973) EPRS PPICE MF-$0.75 HC-$1.50 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Applied Linguistics; Language Development; *Language Planning; Language Role; Language Standardization; Linguistics; Linguistic Theory; Official Languages; Social Planning; *Sociolinguistics ABSTPACT Language planning involves decisions of two basic types: those pertaining to language choice and those pertaining to language development. linguistic theory is needed to evaluate the structural suitability of candidate languages, since both official and national languages mast have a high level of standardizaticn as a cultural necessity. On the other hand, only a braodly conceived and functionally oriented linguistics can serve as a basis for choosiag one language rather than another. The role of linguistics in the area of language development differs somewhat depending on whether development is geared in a technological and scientific or a literary, artistic direction. In the first case, emphasis is on the development of terminologies, and in the second case, on that of grammatical devices and styles. Linguistics can provide realistic and practical arguments in favor of language development, and a detailed, technical understanding of such development, as well as methodological skills. Linguists can and must function as consultants to those who actually make decisions about language planning. For too long linguists have pursued only those aims generated within their own field. They must now broaden their scope to achieve the kind of understanding of language that is necessary for a productive approach to concrete language problems. -

New Paradigm for the Study of Simultaneous V. Sequential Bilingualism

New Paradigm for the Study of Simultaneous v. Sequential Bilingualism Suzanne Flynn1, Claire Foley1 and Inna Vinnitskaya2 1MIT and 2University of Ottawa 1. Introduction Mastering multiple languages is a commonplace linguistic achievement for most of the world’s population. Chomsky (in Mukherji et al. 2000) notes that “In most of human history and in most parts of the world today, children grow up speaking a variety of languages…” Clearly, multilingualism “is just a natural state of the human mind.” Notably, most of this language learning occurs in untutored, naturalistic settings and throughout the lifespan of an individual. The false sense of language homogeneity and monolingualism that is often heralded in the United States, at least in certain regional sections, is clearly a historical artifact. As Chomsky notes: Even in the United States the idea that people speak one language is not true. Everyone grows up hearing many different languages. Sometimes they are called “dialects or stylistic variants or whatever” but they are really different languages. It is just that they are so close to each other that we don’t bother calling them different languages (Chomsky, in Mukherji et al., 2000:19 ) A conclusion is that every individual, by virtue of living within a community, is bilingual1 in some sense. Further, this means that in the same sense there is essentially universal multilingualism in the world. Despite the centrality of multilingualism to the human experience, however, questions persist concerning how learners construct new language