Zone Pricing in Theory and Practice 05/06/2016 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Implementing Pricing Schemes to Meet a Variety of Transportation Goals 09/26/2019 6

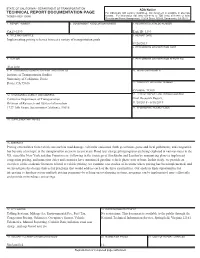

STATE OF CALIFORNIA • DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION ADA Notice TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE For individuals with sensory disabilities, this document is available in alternate TR0003 (REV 10/98) formats. For information call (916) 654-6410 or TDD (916) 654-3880 or write Records and Forms Management, 1120 N Street, MS-89, Sacramento, CA 95814. 1. REPORT NUMBER 2. GOVERNMENT ASSOCIATION NUMBER 3. RECIPIENT'S CATALOG NUMBER CA19-3399 Task ID: 3399 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. REPORT DATE Implementing pricing schemes to meet a variety of transportation goals 09/26/2019 6. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION CODE 7. AUTHOR 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NO. Alan Jenn 9. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS 10. WORK UNIT NUMBER Institute of Transportation Studies University of California, Davis 11. CONTRACT OR GRANT NUMBER Davis, CA 95616 65A0686, TO 09 12. SPONSORING AGENCY AND ADDRESS 13. TYPE OF REPORT AND PERIOD COVERED California Department of Transportation Final Research Report, Division of Research and System Information 11/20/2018 - 6/30/2019 1727 30th Street, Sacramento California, 95618 14. SPONSORING AGENCY CODE 15. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES 16. ABSTRACT Pricing externalities from vehicle use such as road damage, vehicular emissions (both greenhouse gases and local pollutants), and congestion has become a hot topic in the transportation sector in recent years. Road user charge pilot programs are being explored in various states in the US, cities like New York and San Francisco are following in the footsteps of Stockholm and London by announcing plans to implement congestion pricing, and numerous cities and countries have announced gasoline vehicle phase-outs or bans. In this study, we provide an overview of the academic literature related to vehicle pricing, we examine case studies of locations where pricing has been implemented, and we investigate the design choices for programs that would address each of the three externalities. -

Pricing out Congestion

RESEARCH NOTE PRICING OUT CONGESTION Experiences from abroad Patrick Carvalho*† 28 January 2020 I will begin with the proposition that in no other major area are pricing practices so irrational, so out of date, and so conducive to waste as in urban transportation. — William S. Vickrey (1963)1 Summary As part of The New Zealand Initiative’s transport research series, this study focuses on the international experiences around congestion pricing, i.e. the use of road charges encouraging motorists to avoid traveling at peak times in busy routes. More than just a driving nuisance, congestion constitutes a serious global economic problem. By some estimates, congestion costs the world as much as a trillion dollars every year. In response, cities across the globe are turning to decades of scientific research and empirical support in the use of congestion charges to manage road overuse. From the first congestion charging implementation in Singapore in 1975 to London, Stockholm and Dubai in the 2000s to the expected 2021 New York City launch, myriad road pricing schemes are successfully harnessing the power of markets to fix road overcrowding – and providing valuable lessons along the way. In short, congestion charging works. The experiences of these international cities can be an excellent blueprint for New Zealand to learn from and tailor a road pricing scheme that is just right for us. By analysing the international experience on congestion pricing, this research note provides further insights towards a more rational, updated and un-wasteful urban transport system. When the price is right, a proven solution to chronic road congestion is ours for the taking. -

How Effective Are Employer-Subsidized Commute

Can Employer-Subsidized Commute Assistance Programs be Effective in a Free Parking Environment? The City of San José and the Eco-Pass Program By Ray Salvano June 2009 A Thesis Quality Research Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Masters of Science in Transportation Management Mineta Transportation Institute San Jose State University San José, California Can Employer-Subsidized Commute Assistance Programs be Effective in a Free Parking Environment? The City of San José and the Eco-Pass Program ________________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ 3 CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTION 1.1 Overview of the Issue ....................................................................................... 5 1.2 What is an Eco-Pass? ........................................................................................ 6 1.3 The City of San José at a Glance ...................................................................... 6 1.4 Research Objective and Report Organization ................................................... 9 CHAPTER 2 - LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1 Introduction ..................................................................................................... 11 2.2 Focused Literature Review ............................................................................. 11 2.3 Broad-based Literature Review ..................................................................... -

The Effects of Road Pricing on Driver Behavior and Air Pollution

The effects of road pricing on driver behavior andair pollution Matthew Gibson, Maria Carnovale To cite this version: Matthew Gibson, Maria Carnovale. The effects of road pricing on driver behavior and air pollution. Journal of Urban Economics, Elsevier, 2015, 89, pp.62-73. 10.1016/j.jue.2015.06.005. hal-01589743 HAL Id: hal-01589743 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01589743 Submitted on 19 Sep 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The eects of road pricing on driver behavior and air pollution Matthew Gibsona,∗, Maria Carnovaleb aDepartment of Economics, Williams College, Schapiro Hall, 24 Hopkins Hall Dr., Williamstown MA 01267 bCERTeT, Università Bocconi and Duke University, Duke Box 90239, Durham, NC 27708 Abstract Exploiting the natural experiment created by an unanticipated court injunction, we evaluate driver responses to road pricing. We nd evidence of intertemporal substitution toward unpriced times and spatial substitution toward unpriced roads. The eect on trac volume varies with public transit availability. Net of these responses, Milan's pricing policy reduces air pollution substantially, generating large welfare gains. In addition, we use long-run policy changes to estimate price elasticities. -

The Efficacy of Congestion Pricing

University of Tennessee at Chattanooga UTC Scholar Student Research, Creative Works, and Honors Theses Publications 5-2016 The efficacy of congestion pricing Zachary J. Ridder University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.utc.edu/honors-theses Part of the Economics Commons Recommended Citation Ridder, Zachary J., "The efficacy of congestion pricing" (2016). Honors Theses. This Theses is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research, Creative Works, and Publications at UTC Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UTC Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Efficacy of Congestion Pricing By Zack Ridder Departmental Honors Thesis The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Economics Department Project Direction: Dr. Leila Pratt Examination Date: 3/30/16 Examination Committee: Dr. Leila Pratt Dr. Bruce Hutchinson Dr. James Guilfoyle Dr. David Giles The Efficacy of Congestion Pricing By Zack Ridder 1 I. Introduction As the number of vehicles continues to climb road congestion will become a more prominent feature of urban centers and will likely worsen over time. This thesis will show that the most simple and effective way to combat congestion is the implementation of road pricing schemes in and around major metropolitan areas. For the most part the benefits of such a system outweigh the potential costs. These tolling systems force commuters to internalize the marginal social cost of driving, as opposed to only paying the average social cost and incurring a deadweight loss. This paper will first provide a review of the literature, tracing the theoretical development of congestion pricing from its early roots to modern studies. -

Analysing the Heavy Goods Vehicle “Écotaxe” in France: Why Did a Promising Idea Fail in Implementation? T

Transportation Research Part A 118 (2018) 147–173 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Transportation Research Part A journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/tra Analysing the heavy goods vehicle “écotaxe” in France: Why did a promising idea fail in implementation? T Patrick Rigot-Müller Maynooth University, School of Business, Maynooth, Co. Kildare, Ireland ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: In October 2014, France abandoned the implementation of the écotaxe, a major country-wide Road tax acceptance Electronic Tolling System (ETS) designed to charge for the use of national and local roads, which Transport policy were not covered by the traditional toll system. The écotaxe originated from a political consensus Freight transport and was designed with the collaboration of business stakeholders. However, unforeseen im- Green taxation plementation difficulties resulted in a renouncement at a late stage, when the infrastructure was Greater Paris already deployed. According to a recent report from the French body in charge of auditing public expenses, it generated a cost of 953 million euros. In analysing what happened during the policy delivery stage, this paper provides insights to policymakers in countries where ETS is envisaged. The ETS system was piloted in summer 2013, and the “go live” date was 1st September 2014. Data was collected ‘live’, in March 2014, featuring 21 interviews, with the aim of better un- derstanding the expected challenges and impacts on the business stakeholders. At the time, stakeholders accepted that the project would go ahead: while further implementation challenges remained, few anticipated them to fully derail the project within 6 months. Retrospective ana- lysis of the data collected in March 2014 can help to deepen policymakers’ insights into why the project ultimately failed and better understand the main lessons to be learnt. -

Impact of Transportation-Related Environmental

Impact of Transportation - Related Environmental Initiatives Project # C021273, 22 May 2020 Impact of Transportation- Related Environmental Initiatives Final Report 22nd May, 2020 Project C021273 Impact of Transportation - Related Environmental Initiatives Project # C021273, 22 May 2020 Contents • Executive summary • Project report • Appendix – I (Project report addendum) • Appendix – II (Movement 101) • Appendix – III (Summary of research) 2 Impact of Transportation - Related Environmental Initiatives Project # C021273, 22 May 2020 37 U.S. and global Movements were assessed prior to shortlisting 14 U.S. specific Movements for long term impact assessment Movement Emissions, fuel economy Alternative Tolls, congestion pricing Mobility Category: and carbon pricing fuels and telecommuting initiatives Low Carbon Fuel Connected and Subsidies / Incentives Congestion pricing Standard autonomous vehicles ZEV Mandate Biofuels blending Telecommuting Shared mobility Charging Infrastructure Movements shortlisted CAFE standard Global Movements assessed Movements excluded for further • China Corporate Average Fuel • EU Fuels Quality Directive (FQD) • Vehicle retirement program assessment Transportation Consumption (CAFC) standard Tolls • London Congestion Charge • Tolls Climate Initiative (TCI) • EU Emission Standards • Milan Area C • Parking benefits • Japan Energy Conservation Law • Trängselskatt I Stockholm • Passenger drones • South Korea Average Fuel Economy • Canada Telework Policy • Multi-modal transit Carbon pricing (AFE) program • EU Energy -

Milan's Pollution Charge

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Institutional Repository of the Freie Universität Berlin Milan’s pollution charge: sustainable transport and the politics of evidence Giulio Mattioli, Mario Boffi & Matteo Colleoni, Dipartimento di Sociologia e Ricerca Sociale, Università degli Studi di Milano-Bicocca Paper presented at the Berlin Conference 2012 on the Human Dimensions of Global Environmental Change – “Evidence for Sustainable Development”, Berlin 5-6 October 2012 Abstract The city of Milan, one of the most car-dependent and polluted in Europe, is also among the few to have introduced a road pricing measure. The story of how this happened is of great interest, for it shows how EU regulations, scientific evidence and political action at the local level have concurred to bring about change in the city’s transport policy. Unlike the well-known cases of London and Stockholm, it is concerns for the levels of pollution (rather than congestion) that have led to the introduction of the “Ecopass” scheme in 2008. Accordingly, in the following years the public debate has focused on the effectiveness of this pollution charge in reducing PM 10 – a pollutant with adverse health impacts. Based on the analysis of media coverage and official reports, this paper argues that EU regulations had a crucial role in determining the newsworthiness of PM 10 in Milan. Media and public concerns have then put increasing pressure on politicians to find a solution to the “emergency”. The dubious effectiveness of Ecopass in reducing PM 10 levels then has had two kinds of consequences. -

Ecopass Scheme in Milan: Three Years Later

An economic, environmental and transport evaluation of the Ecopass scheme in Milan: three years later Romeo Danielis a1, Lucia Rotaris a, Edoardo Marcucci b, Jérôme Massiani c aUniversity of Trieste, Italy - bUniversity of Roma 3, Italy - cUniversity of Ca’ Foscari, Venice, Italy Abstract The paper provides an evaluation of the Ecopass scheme for the years 2008, 2009 and 2010. The term Ecopass conveys the stated political objective of the scheme: a PASS to improve the quality of the urban environment (ECO). The scheme has actually improved the air quality in Milan, although the recommended PM 10 threshold is still exceeded for a larger number of days than that recommended by EU directives. This paper estimates the costs and benefits of the scheme three years after its implementation using the same methodology applied in Rotaris et al. (2010) for the year 2008. It results that the benefits still exceed the costs by an increasing amount, but at an annual decreasing rate of improvement. The Ecopass scheme has proved beneficial, but it seems to have exhausted its potential: little further gains in environmental quality could be obtained via a fiscal incentive to improve the abatement technology of the vehicles. The new administration, elected in June 2011, is faced with the task of deciding whether to dismiss, maintain or change the Ecopass scheme. The prevailing idea coming from the Ecopass Commission and from the advocacy groups is to extend both the area of application and the number of classes subject to the charge. A move from a pollution charge to a congestion charge, or at least a combination of a pollution and a congestion charge is envisaged. -

Equitable Congestion Pricing

UC Office of the President ITS reports Title Equitable Congestion Pricing Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/17h3k4db Authors Cohen D’Agostino, Mollie Pellaton, Paige White, Brittany Publication Date 2020-12-01 DOI 10.7922/G2RF5S92 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California RESEARCH REPORT Institute of Transportation Studies Equitable Congestion Pricing Mollie Cohen D’Agostino, Policy Director, 3 Revolutions Future Mobility Program, Institute of Transportation Studies, University of California, Davis Paige Pellaton, PhD Candidate, Department of Political Science, University of California, Davis Brittany White, Graduate Student Researcher, M.S., Community Development Graduate Group, University of California, Davis December 2020 Report No.: UC-ITS-2020-21a | DOI: 10.7922/G2RF5S92 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. UC-ITS-2020-21a Accession No. N/A N/A 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Equitable Congestion Pricing December 2020 6. Performing Organization Code ITS-Davis 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Mollie Cohen D’Agostino, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3689-9471 UCD-ITS-RR-20-88 Paige Pellaton, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9960-1927 Brittany White, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1490-3991 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. Institute of Transportation Studies, Davis N/A 1605 Tilia Street 11. Contract or Grant No. Davis, Ca 95616 UC-ITS-2020-21a 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered The University of California Institute of Transportation Studies Final Report (October 2019 – September 2020) www.ucits.org 14. -

West Midlands Low Emission Zones: Technical Feasibility Study Economic and Health Impacts of Air Pollution Reductions

West Midlands Low Emission Zones: Technical Feasibility Study Economic and health impacts of air pollution reductions UNRATIFIED Report for Birmingham City Council Ricardo-AEA/R/ED58179 WP2/3 Issue Number 1 Date 23/02/2015 West Midlands Low Emission Zones: Technical Feasibility Study Customer: Contact: Birmingham City Council Beth Conlan Gemini Building, Harwell, Didcot, OX11 0QR Customer reference: t: 01235 75 3480 Click here to enter text. e: [email protected] Ricardo-AEA is certificated to ISO9001 and ISO14001 Confidentiality, copyright & reproduction: This report is the Copyright of Birmingham city Council and has been prepared by Ricardo-AEA Ltd under contract to Author: Birmingham City Council. The contents of this report may not be reproduced in whole or John Abbott in part, nor passed to any organisation or person without the specific prior written Approved By: permission of BirminghamUNRATIFIED City Council. Beth Conlan Ricardo-AEA Ltd accepts no liability whatsoever to any third party for any loss or Date: damage arising from any interpretation or use of the information contained in this 23 February 2015 report, or reliance on any views expressed therein. Ricardo-AEA reference: Ref: ED58179 WP2/3- Issue Number 1 Ref: Ricardo-AEA/R/ED58179 WP2/3/Issue Number 1 i West Midlands Low Emission Zones: Technical Feasibility Study Executive summary West Midland Metropolitan Local Authorities, including Birmingham, Coventry, Dudley, Sandwell, Solihull, Walsall and Wolverhampton have developed the Low Emission Towns and Cities (LETC) Programme in response to the challenges posed by road transport emissions. The West Midlands Urban Area includes the most extensive area outside London in terms of exceeding the EU Limit Value for nitrogen dioxide (NO2). -

Pay for Urban Transport

WHO PAYS WHAT FOR URBAN TRANSPORT? Handbook of good practices Edition 2014 The Agence Française de Développement (AFD) and the Ministry of Ecology, Sustainable Development and Energy (MEDDE) produced this guide, with a first version published in November 2009. The publication of the first version was supervised by a steering committee composed of Xavier Hoang for the AFD, Gilles David and Alexandre Strauss for MEDDE, and edited by CODATU: Françoise Méteyer-Zeldine, in collaboration with Laurence Lafon and Xavier Godard. The technical proof-reading was entrusted to CERTU: Thierry Gouin and Patricia Varnaison-Revolle. The update of the document in 2014 was managed by Xavier Hoang for the AFD, in cooperation with Gwendoline Rouzière and Maxime Jebali for the MEDDE. The update was coordinated by Julien Allaire (CODATU), with support from Françoise Méteyer-Zeldine and Thierry Gouin (CEREMA), Kamel Bouhmad (consultant). Contributions were also made by: Olivier Ratheaux, Lise Breuil and Guillaume Meyssonier (AFD Paris), Gautier Kohler (AFD Delhi), Marion Sybillin (AFD Dhaka) and Yildiz Kuruoglu (AFD Istanbul). This guide is a working tool - the AFD and MEDDE are in no way responsible for how it is used and do not necessarily share all its conclusions. It can be downloaded on the CODATU website: www.codatu.org The bibliographical references used in this work are given at the end of the document. _Contents _Foreword 5 _Introduction The Challenges of funding urban transport 7 0.1 Challenges of urban mobility 8 0.2 Which modes of transport should