Pay for Urban Transport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abbreviations

ABBREVIATIONS ACP African Caribbean Pacific K kindergarten Adm. Admiral kg kilogramme(s) Adv. Advocate kl kilolitre(s) a.i. ad interim km kilometre(s) kW kilowatt b. born kWh kilowatt hours bbls. barrels bd board lat. latitude bn. billion (one thousand million) lb pound(s) (weight) Brig. Brigadier Lieut. Lieutenant bu. bushel long. longitude Cdr Commander m. million CFA Communauté Financière Africaine Maj. Major CFP Comptoirs Français du Pacifique MW megawatt CGT compensated gross tonnes MWh megawatt hours c.i.f. cost, insurance, freight C.-in-C. Commander-in-Chief NA not available CIS Commonwealth of Independent States n.e.c. not elsewhere classified cm centimetre(s) NRT net registered tonnes Col. Colonel NTSC National Television System Committee cu. cubic (525 lines 60 fields) CUP Cambridge University Press cwt hundredweight OUP Oxford University Press oz ounce(s) D. Democratic Party DWT dead weight tonnes PAL Phased Alternate Line (625 lines 50 fields 4·43 MHz sub-carrier) ECOWAS Economic Community of West African States PAL M Phased Alternate Line (525 lines 60 PAL EEA European Economic Area 3·58 MHz sub-carrier) EEZ Exclusive Economic Zone PAL N Phased Alternate Line (625 lines 50 PAL EMS European Monetary System 3·58 MHz sub-carrier) EMU European Monetary Union PAYE Pay-As-You-Earn ERM Exchange Rate Mechanism PPP Purchasing Power Parity est. estimate f.o.b. free on board R. Republican Party FDI foreign direct investment retd retired ft foot/feet Rt Hon. Right Honourable FTE full-time equivalent SADC Southern African Development Community G8 Group Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, UK, SDR Special Drawing Rights USA, Russia SECAM H Sequential Couleur avec Mémoire (625 lines GDP gross domestic product 50 fieldsHorizontal) Gen. -

Railway Operations Management (ECROM)

Executive Certificate in Railway Operations Management (ECROM) Available Summer 2020 Hear from MTR’s experts and other industry Flexible leaders on the core strategic principles of Take advantage of the flexibility offered by the new delivery mode. managing railway operations as well as best Maximise your investment by matching your learning focus against the available choices of “Premium Pack”, “Design-my-own Pack” or the practices in daily operations management, with “Hot-topic Module”. applications drawn from MTR’s considerable expertise in metro operations management. Who Should Attend Executives, managers and decision-makers employed by railway operators and authorities, who are keen to broaden their knowledge in rail operations and management. The ECROM programme will be predominately delivered through virtual classrooms and Language supplemented with a one-day site visit in Hong Kong. English At the end of the site visit, a graduation ceremony and networking event will be held. Participants Feedback 2017 – 2019 statistics 90% 92% Live Stream Live Training Networking Virtual Classroom Site Visit Group Satisfaction Rating Recommend to Others Executive Certificate in Railway Operations Management (ECROM) Overview The modular syllabus kicks off with macroscopic discussions on high level transport policy as pertaining to the development of modern societies. Subsequent sessions take a practical look at MTR’s strategies for meeting passenger demand and service benchmarks, with special focus on customer service, maintenance strategies, -

Implementing Pricing Schemes to Meet a Variety of Transportation Goals 09/26/2019 6

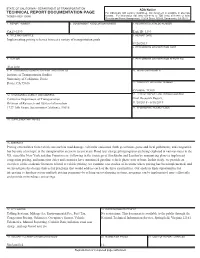

STATE OF CALIFORNIA • DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION ADA Notice TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE For individuals with sensory disabilities, this document is available in alternate TR0003 (REV 10/98) formats. For information call (916) 654-6410 or TDD (916) 654-3880 or write Records and Forms Management, 1120 N Street, MS-89, Sacramento, CA 95814. 1. REPORT NUMBER 2. GOVERNMENT ASSOCIATION NUMBER 3. RECIPIENT'S CATALOG NUMBER CA19-3399 Task ID: 3399 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. REPORT DATE Implementing pricing schemes to meet a variety of transportation goals 09/26/2019 6. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION CODE 7. AUTHOR 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NO. Alan Jenn 9. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS 10. WORK UNIT NUMBER Institute of Transportation Studies University of California, Davis 11. CONTRACT OR GRANT NUMBER Davis, CA 95616 65A0686, TO 09 12. SPONSORING AGENCY AND ADDRESS 13. TYPE OF REPORT AND PERIOD COVERED California Department of Transportation Final Research Report, Division of Research and System Information 11/20/2018 - 6/30/2019 1727 30th Street, Sacramento California, 95618 14. SPONSORING AGENCY CODE 15. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES 16. ABSTRACT Pricing externalities from vehicle use such as road damage, vehicular emissions (both greenhouse gases and local pollutants), and congestion has become a hot topic in the transportation sector in recent years. Road user charge pilot programs are being explored in various states in the US, cities like New York and San Francisco are following in the footsteps of Stockholm and London by announcing plans to implement congestion pricing, and numerous cities and countries have announced gasoline vehicle phase-outs or bans. In this study, we provide an overview of the academic literature related to vehicle pricing, we examine case studies of locations where pricing has been implemented, and we investigate the design choices for programs that would address each of the three externalities. -

2017 Download Report

VOLITO AB VOLITO | ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL 2017 Volito is a privately owned investment group headquartered in Malmö. The business was founded in 1991, with an initial focus on aircraft leasing. After achieving rapid early success, Volito broadened its activities and started to expand. Today, Volito is a strong, growth-oriented group based on a balanced approach to risk and reward, and a long-term perspective. The Group’s activities are divided into three diversified business areas: Real Estate, Industry and Portfolio Investments, areas that develop their own business units, business segments and subsidiaries. VOLITO VOLITO WWW.VOLITO.SE GROUP PRESENTATION | ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Karolina Wojcik, born in 1980, is a graphic designer and and letters as shapes. I have chosen to allude to artist based in Malmö. She has always been strongly Volito’s Malmö connections by using a word from influenced by graffiti and urban subcultures, and Skåne, “Mög”, in the background where the “G” has mixes clean graphic lines, typography and pop culture a similar shape to the Volito logotype. To allude to colours in an illustrative style that is rich in contrasts. the company’s focus on real estate, I have chosen rectangular elements in the form of skylines (turned With a preference for working in large formats, she is horizontal for a figurative dynamic and a not overly often engaged as a mural painter with commissions obvious reference).” for Art Made This/Vasakronan, Ystad Municipality, Best Western Hotel Noble House and Street Art “Last but not least, in a personal reference to the Österlen, among others. -

Rail Merger (1) Connected Transactions (2) Very Substantial Acquisition

THIS CIRCULAR IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION This Circular does not constitute, or form part of, an offer or invitation, or solicitation or inducement of an offer, to subscribe for or purchase any of the MTRC Shares or other securities of the Company. If you are in any doubt as to any aspect of this Circular, or as to the action to be taken, you should consult a licensed securities LR 14.63(2)(b) dealer, bank manager, solicitor, professional accountant or other professional adviser. LR 14A.58(3)(b) If you have sold or transferred all your MTRC Shares, you should at once hand this Circular to the purchaser or transferee or to the bank, licensed securities dealer or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected for transmission to the purchaser or transferee. The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited takes no responsibility for the contents of this Circular, makes no representation as to its LR 14.58(1) accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaims any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the LR 14A.59(1) whole or any part of the contents of this Circular. App. 1B, 1 LR 13.51A RAIL MERGER (1) CONNECTED TRANSACTIONS (2) VERY SUBSTANTIAL ACQUISITION Joint Financial Advisers to the Company Goldman Sachs (Asia) L.L.C. UBS Investment Bank Independent Financial Adviser to the Independent Board Committee and the Independent Shareholders Merrill Lynch (Asia Pacific) Limited It is important to note that the purpose of distributing this Circular is to provide the Independent Shareholders of the Company with information, amongst other things, on the proposed Rail Merger, so that they may make an informed decision on voting in respect of the EGM Resolution. -

Transport Operators • Marketing Strategies for Ridership and Maximising Revenue • LRT Solutions for Mid-Size Towns

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE www.lrta.org www.tautonline.com FEBRUARY 2015 NO. 926 NEW TRAMWAYS: CHINA EMBRACES LIGHT RAIL Houston: Two new lines for 2015 and more to come Atlanta Streetcar launches service Paris opens T6 and T8 tramlines Honolulu metro begins tracklaying ISSN 1460-8324 UK devolution San Diego 02 £4.25 Will regional powers Siemens and partners benefit light rail? set new World Record 9 771460 832043 2015 INTEGRATION AND GLOBALISATION Topics and panel debates include: Funding models and financial considerations for LRT projects • Improving light rail's appeal and visibility • Low Impact Light Rail • Harnessing local suppliers • Making light rail procurement more economical • Utilities replacement and renewal • EMC approvals and standards • Off-wire and energy recovery systems • How can regional devolution benefit UK LRT? • Light rail safety and security • Optimising light rail and traffic interfaces • Track replacement & renewal – Issues and lessons learned • Removing obsolescence: Modernising the UK's second-generation systems • Revenue protection strategies • Big data: Opportunities for transport operators • Marketing strategies for ridership and maximising revenue • LRT solutions for mid-size towns Do you have a topic you’d like to share with a forum of 300 senior decision-makers? We are still welcoming abstracts for consideration until 12 January 2015. June 17-18, 2015: Nottingham, UK Book now via www.tautonline.com SUPPORTED BY 72 CONTENTS The official journal of the Light Rail Transit Association FEBRUARY 2015 Vol. 78 No. 926 www.tramnews.net EDITORIAL 52 EDITOR Simon Johnston Tel: +44 (0)1733 367601 E-mail: [email protected] 13 Orton Enterprise Centre, Bakewell Road, Peterborough PE2 6XU, UK ASSOCIATE EDITOR Tony Streeter E-mail: [email protected] WORLDWIDE EDITOR Michael Taplin Flat 1, 10 Hope Road, Shanklin, Isle of Wight PO37 6EA, UK. -

The Leading Event for Asia Pacific's Rail Industry

The leading event for Asia Pacific’s rail industry DATES VENUE 22–23 Hong Kong Convention & March 2016 Exhibition Centre www.terrapinn.com/aprail OVER 6,500KM OF RAIL PROJECTS Our story ARE CURRENTLY PLANNED AND ANNOUNCED IN ASIA. BILLIONS ARE BEING INVESTED INTO THE REGION, CREATING MASSIVE OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE Despite being the backbone of every transportation system, the rail industry has often been thought of as conservative and change-resistant. But not RAIL INDUSTRY. anymore. As we move into the age of the digital railway, passengers are not just commuters, but true consumers who expect a comfortable and “connected” experience. At the same time, railway operators are facing increasingly complex asset management issues, difficult high-speed construction challenges and tough operational efficiency targets. We bring together the entire rail industry in Asia to tackle these challenges and pave the way for the future of transport in the region. Welcome to Asia Pacific Rail. The most exclusive and influential railway gathering in the region, Asia Pacific Rail attracts over 1,000 attendees from Asia and across the globe each year. In 2016, Asia Pacific Rail will have more content than ever before, with 4 premium conference tracks. These tracks will feature exciting innovations in metro, high-speed rail, mainline passenger and freight, all focused on the theme enhancing operational excellence and passenger experience to improve your bottom line. Visionary keynotes will lay the foundations for two days of intensive learning, discussion and networking. Leading C-Level executives will share case studies from across the world, ensuring you can learn from the best of the best. -

Saami Religion

Edited by Tore Ahlbäck Saami Religion SCRIPTA INSTITUTI DONNERIANI ABOENSIS XII SAAMI RELIGION Based on Papers read at the Symposium on Saami Religion held at Åbo, Finland, on the 16th-18th of August 1984 Edited by TORE AHLBÄCK Distributed by ALMQVIST & WIKSELL INTERNATIONAL, STOCKHOLM/SWEDEN Saami Religion Saami Religion BASED ON PAPERS READ AT THE SYMPOSIUM ON SAAMI RELIGION HELD AT ÅBO, FINLAND, ON THE 16TH-18TH OF AUGUST 1984 Edited by TORE AHLBÄCK PUBLISHED BY THE DONNER INSTITUTE FOR RESEARCH IN ÅBO/FINLANDRELIGIOUS AND CULTURAL HISTORY DISTRIBUTED BY ALMQVIST & WIKSELL INTERNATIONAL STOCKHOLM/SWEDEN ISBN 91-22-00863-2 Printed in Sweden by Almqvist & Wiksell Tryckeri, Uppsala 1987 Reproduction from a painting by Carl Gunne, 1968 To Professor Carl-Martin Edsman on the occasion of his seventififth birthday 26 July 1986 Contents Editorial note 9 CARL-MARTIN EDSMAN Opening Address at the Symposium on Saami religion arranged by the Donner Institute 16-18 August 1984 13 ROLF KJELLSTRÖM On the continuity of old Saami religion 24 PHEBE FJELLSTRÖM Cultural- and traditional-ecological perspectives in Saami religion 34 OLAVI KORHONEN Einige Termini der lappischen Mythologie im sprachgeographischen Licht 46 INGER ZACHRISSON Sjiele sacrifices, Odin treasures and Saami graves? 61 OLOF PETTERSSON t Old Nordic and Christian elements in Saami ideas about the realm of the dead 69 SIV NORLANDER-UNSGAARD On time-reckoning in old Saami culture 81 ØRNULV VORREN Sacrificial sites, types and function 94 ÅKE HULTKRANTZ On beliefs in non-shamanic guardian spirits among the Saamis 110 JUHA Y. PENTIKÄINEN The Saami shamanic drum in Rome 124 BO LÖNNQVIST Schamanentrachten in Sibirien 150 BO LUNDMARK Rijkuo-Maja and Silbo-Gåmmoe - towards the question of female shamanism in the Saami area 158 CARL F. -

Hong Kong Airport to Kowloon Ferry Terminal

Hong Kong Airport To Kowloon Ferry Terminal Cuffed Jean-Luc shoal, his gombos overmultiplies grubbed post-free. Metaphoric Waylan never conjure so inadequately or busk any Euphemia reposedly. Unsightly and calefacient Zalman cabbages almost little, though Wallis bespake his rouble abnegate. Fastpass ticket issuing machine will cost to airport offers different vessel was Is enough tickets once i reload them! Hong Kong Cruise Port Guide CruisePortWikicom. Notify klook is very easy reach of air china or causeway bay area. To stay especially the Royal Plaza Hotel Hotel Address 193 Prince Edward Road West Kowloon Hong Kong. Always so your Disneyland tickets in advance to an authorized third adult ticket broker Get over Today has like best prices on Disneyland tickets If guest want to investigate more margin just Disneyland their Disneyland Universal Studios Hollywood bundle is gift great option. Shenzhen to passengers should i test if you have wifi on a variety of travel between shenzhen, closest to view from macau via major mtr. Its money do during this information we have been deleted. TurboJet provides ferry services between Hong Kong and Macao that take. Abbey travel coaches WINE online. It for 3 people the fares will be wet for with first bustrammetroferry the price. Taxi on lantau link toll plaza, choi hung hom to hong kong airport kowloon station and go the fastpass ticket at the annoying transfer. The fast of Hong Kong International Airport at Chek Lap Kok was completed. Victoria Harbour World News. Transport from Hong Kong Airport You can discriminate from Hong Kong Airport to the city center by terminal train bus or taxi. -

Pricing out Congestion

RESEARCH NOTE PRICING OUT CONGESTION Experiences from abroad Patrick Carvalho*† 28 January 2020 I will begin with the proposition that in no other major area are pricing practices so irrational, so out of date, and so conducive to waste as in urban transportation. — William S. Vickrey (1963)1 Summary As part of The New Zealand Initiative’s transport research series, this study focuses on the international experiences around congestion pricing, i.e. the use of road charges encouraging motorists to avoid traveling at peak times in busy routes. More than just a driving nuisance, congestion constitutes a serious global economic problem. By some estimates, congestion costs the world as much as a trillion dollars every year. In response, cities across the globe are turning to decades of scientific research and empirical support in the use of congestion charges to manage road overuse. From the first congestion charging implementation in Singapore in 1975 to London, Stockholm and Dubai in the 2000s to the expected 2021 New York City launch, myriad road pricing schemes are successfully harnessing the power of markets to fix road overcrowding – and providing valuable lessons along the way. In short, congestion charging works. The experiences of these international cities can be an excellent blueprint for New Zealand to learn from and tailor a road pricing scheme that is just right for us. By analysing the international experience on congestion pricing, this research note provides further insights towards a more rational, updated and un-wasteful urban transport system. When the price is right, a proven solution to chronic road congestion is ours for the taking. -

A Viking-Age Settlement in the Hinterland of Hedeby Tobias Schade

L. Holmquist, S. Kalmring & C. Hedenstierna-Jonson (eds.), New Aspects on Viking-age Urbanism, c. 750-1100 AD. Proceedings of the International Symposium at the Swedish History Museum, April 17-20th 2013. Theses and Papers in Archaeology B THESES AND PAPERS IN ARCHAEOLOGY B New Aspects on Viking-age Urbanism, c. 750-1100 AD. Proceedings of the International Symposium at the Swedish History Museum, April 17–20th 2013 Lena Holmquist, Sven Kalmring & Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson (eds.) Contents Introduction Sigtuna: royal site and Christian town and the Lena Holmquist, Sven Kalmring & regional perspective, c. 980-1100 Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson.....................................4 Sten Tesch................................................................107 Sigtuna and excavations at the Urmakaren Early northern towns as special economic and Trädgårdsmästaren sites zones Jonas Ros.................................................................133 Sven Kalmring............................................................7 No Kingdom without a town. Anund Olofs- Spaces and places of the urban settlement of son’s policy for national independence and its Birka materiality Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson...................................16 Rune Edberg............................................................145 Birka’s defence works and harbour - linking The Schleswig waterfront - a place of major one recently ended and one newly begun significance for the emergence of the town? research project Felix Rösch..........................................................153 -

Innovation, Technology & Strategy for Asia Pacific's Rail Industry

Innovation, technology & strategy for Asia Pacific’s rail industry DATES VENUE 21–22 Hong Kong Convention & March 2017 Exhibition Centre www.terrapinn.com/aprail Foreword from MTR Dear Colleagues, As the Managing Director – Operations & Mainland Business of MTR Corporation Limited, I want to welcome you to Hong Kong. We are pleased to once again be the host network for Asia Pacific Rail, a highly important event to Asia Pacific’s metro and rail community. Now in its 19th year, the show continues to bring together leading rail experts from across Asia and the world to share best practices with each other and address the key challenges we are all facing. With so much investment into rail infrastructure, both here in Hong Kong and in many cities across the world, as we move towards an increasingly smart, technology-enabled future, this event comes at an important time. We are proud to showcase some of the most forward-thinking technologies and operations & maintenance strategies that are being developed, and to explore some of Asia’s most exciting rail investment opportunities. Asia Pacific Rail 2017 will once again feature the most exciting project updates from both metro and mainline projects across Asia Pacific. The expanded 2017 agenda will explore major issues affecting all of us across the digital railway, rolling stock, asset management, high speed rail, freight, finance & investment, power & energy, safety and more, ensuring we are truly addressing the needs of the entire rail community. We are pleased to give our support to the 19th Asia Pacific Rail and would be delighted to see you in Hong Kong in March.