1 Genetic, Morphological, and Niche Variation in the Widely Hybridizing Rhus Integrifolia- 2 Rhus Ovata Species Complex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malosma Laurina (Nutt.) Nutt. Ex Abrams

I. SPECIES Malosma laurina (Nutt.) Nutt. ex Abrams NRCS CODE: Family: Anacardiaceae MALA6 Subfamily: Anacardiodeae Order: Sapindales Subclass: Rosidae Class: Magnoliopsida Immature fruits are green to red in mid-summer. Plants tend to flower in May to June. A. Subspecific taxa none B. Synonyms Rhus laurina Nutt. (USDA PLANTS 2017) C. Common name laurel sumac (McMinn 1939, Calflora 2016) There is only one species of Malosma. Phylogenetic analyses based on molecular data and a combination of D. Taxonomic relationships molecular and structural data place Malosma as distinct but related to both Toxicodendron and Rhus (Miller et al. 2001, Yi et al. 2004, Andrés-Hernández et al. 2014). E. Related taxa in region Rhus ovata and Rhus integrifolia may be the closest relatives and laurel sumac co-occurs with both species. Very early, Malosma was separated out of the genus Rhus in part because it has smaller fruits and lacks the following traits possessed by all species of Rhus : red-glandular hairs on the fruits and axis of the inflorescence, hairs on sepal margins, and glands on the leaf blades (Barkley 1937, Andrés-Hernández et al. 2014). F. Taxonomic issues none G. Other The name Malosma refers to the strong odor of the plant (Miller & Wilken 2017). The odor of the crushed leaves has been described as apple-like, but some think the smell is more like bitter almonds (Allen & Roberts 2013). The leaves are similar to those of the laurel tree and many others in family Lauraceae, hence the specific epithet "laurina." Montgomery & Cheo (1971) found time to ignition for dried leaf blades of laurel sumac to be intermediate and similar to scrub oak, Prunus ilicifolia, and Rhamnus crocea; faster than Heteromeles arbutifolia, Arctostaphylos densiflora, and Rhus ovata; and slower than Salvia mellifera. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Ancient Plant Use and the Importance of Geophytes Among the Island Chumash of Santa Cruz

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Ancient Plant Use and the Importance of Geophytes among the Island Chumash of Santa Cruz Island, California A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Kristina Marie Gill Committee in charge: Professor Michael A. Glassow, Chair Professor Michael A. Jochim Professor Amber M. VanDerwarker Professor Lynn H. Gamble September 2015 The dissertation of Kristina Marie Gill is approved. __________________________________________ Michael A. Jochim __________________________________________ Amber M. VanDerwarker __________________________________________ Lynn H. Gamble __________________________________________ Michael A. Glassow, Committee Chair July 2015 Ancient Plant Use and the Importance of Geophytes among the Island Chumash of Santa Cruz Island, California Copyright © 2015 By Kristina Marie Gill iii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my Family, Mike Glassow, and the Chumash People. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to many people who have provided guidance, encouragement, and support in my career as an archaeologist, and especially through my undergraduate and graduate studies. For those of whom I am unable to personally thank here, know that I deeply appreciate your support. First and foremost, I want to thank my chair Michael Glassow for his patience, enthusiasm, and encouragement during all aspects of this daunting project. I am also truly grateful to have had the opportunity to know, learn from, and work with my other committee members, Mike Jochim, Amber VanDerwarker, and Lynn Gamble. I cherish my various field experiences with them all on the Channel Islands and especially in southern Germany with Mike Jochim, whose worldly perspective I value deeply. I also thank Terry Jones, who provided me many undergraduate opportunities in California archaeology and encouraged me to attend a field school on San Clemente Island with Mark Raab and Andy Yatsko, an experience that left me captivated with the islands and their history. -

Rhus Integrifolia (Nutt.) Rothr., LEMONADEBERRY. Shrub Or Small

Rhus integrifolia (Nutt.) Rothr., LEMONADEBERRY. Shrub or small tree, evergreen, sclerophyllous, highly branched with dense canopy, in range 100–600 cm tall; gynodioecious; shoots in full sun with mostly ascending to erect leaves, in early spring forming new shoots from axillary buds below inflorescences, strongly aromatic like wintergreen (Gaultheria) when cut or crushed (having resin ducts with terpenes). Stems: cylindric, limber, when young red and brown with grayish cast from pubescence and scaly waxy plates; producing colorless resin in bark ducts, in ×-section the ducts elliptic, 16–18 arranged in ring; twig bark dull gray, trunk bark with thick, gray flakes; trunk to 40 cm diameter in arborescent forms. Leaves: helically alternate, simple, petiolate, without stipules; petiole 4–12(–15) mm long, reddish, sparsely pubescent and waxy with ± scaly plates; blade broadly elliptic to elliptic-ovate, (15–)25–70 × (10–)20–45 mm, leathery, flat or ± cupped to underside, broadly tapered to round at base, entire or coarsely serrate with shallow teeth and wavy on margins, ± transparent light pink or green at edge, ± obtuse to broadly acute at tip, pinnately veined with principal veins slightly raised on both surfaces, glabrous or with hairs and ± scaly waxy plates along lower midrib, satiny to glaucous, upper surface dark green, lower surface yellow-green. Inflorescence: panicle of spikes having either pistillate flowers or bisexual flowers (separate individuals), panicle 20–70 × 20–50 mm, compact spikes on primary to tertiary branches, many-flowered, -

Pyrophytic Plants Vs. Fire Resistant Plants!

UNIVERSITYOF CALIFORNIA COOPERATIVE EXTENSION run0rilfficv$,flmnastsT,{NT PIJTNI$ Ray Moritz, Fire Ecologistanil TcchnicalAdvisor to FireSafe Madn; and. Pavel Svihra, Horticulture Aduisor,Main and SonomaCounties "White house" and its garden (trace with a dashed line) is a spectacular demonstration of defensible space.Wildfire with cata- clysmic energy swiftly burned adjacent houses and vegetation, yet it died down after reaching the frontier of fire resistant garden. PYROPHYTES They may have loose or papery bark. Plantsthat ignite readily and burn intensely(pyro- . These plants flame (not smolder) when phates)typically sharecertain characteristics: preheated and ignited with a match. They are usually blade-leaf or needle-leaf evergreens. FLAMMABILITY & CONDITION o They have stiff, woody, small or finer lacey The condition of the plant is as importantas its spe- leav"es. cies.Even some"pyrophytic" speciescan be quite fire-resistantif properly maintained. Their leaves and wood usuallv contain volatile waxes, fats, terpenes or oils (drushed leaves have strong od6rs). Depending on its growth form and accessto water, the samespecies may be fire resistantin one envi- ronment and pyrophytic in another.Water-stressed o Their sap $ usually gummy' resinous and has a strong odor. plants that are in poor condition are more pyrophytic. They usually contain plentiful fine, twiggy, A pyrophytic speciesbecomes explosively flamma- drv or dead materials. ble when poorly maintained. South-facing slopes, windy areas,sites with poor soils and urban land- . They may have pubescent (hair covered) leaves. scapesare more stressfulfor plants. (cmcer-related), mce Po1icymayboaddressedtotheAfimativeAc!ionDirector,Unive.sityofcali1bmia,AgriculoreadNafralResources,llll Fire ResistantPlants PYROPTTYTICVBGETATION TYPES : Grasses: Any cured (dry) grass.Nonirrigated, bracken and sword ferns. -

Native Plants the Selection of Plants on This List Is Not Intended to Be Exhaustive

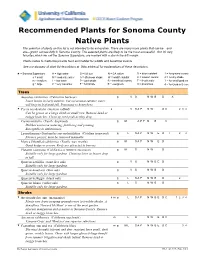

Recommended Plants for Sonoma County Native Plants The selection of plants on this list is not intended to be exhaustive. There are many more plants that can be—and are—grown successfully in Sonoma County. The selected plants are likely to be the most successful. Our 30 very favorites,which we call the Sonoma Superstars, are marked with a star in the left margin. Plants native to California provide food and habitat for wildlife and beneficial insects. See our glossary of plant list descriptors at [http address] for explanations of these descriptors. H = Sonoma Superstars H = high water S = full sun N = CA native D = deer resistant 1 = for ground covers s = small M = moderate water A = afternoon shade W = wildlife habitat C = erosion control 2 = for dry shade m = medium L = low water P = part shade B = beneficial insects T = frost tender 3 = for small gardens g = large V = very low water F = full shade E = evergreen X = poisonous 4 = for Garden Sense Trees Aesculus californica (California buckeye) g V S N W B D X Loses leaves in early summer, but occasional summer water will keep in leaf until fall. Poisonous to honeybees. H Cercis occidentalis (western redbud) s V S A P N W D C 2 3 4 Can be grown as a large shrub or small tree. Remove dead or twiggy branches. Clean up seed pods as they drop. Cornus nuttallii (Pacific dogwood) g M A P F N B C Dislikes excessive watering, fertilizing and pruning. Susceptible to anthracnose. Lyonothamnus floribundus ssp aspleniifolius (Catalina ironwood) g L S A P N W E D T 2 4 Flowers persist; must be removed manually. -

Bibliographies on Coastal Sage Scrub and Related Malacophyllous Shrublands of Other Mediterranean- California Wildlife Type Climates Conservation Bulletin No

Bibliographies on Coastal Sage Scrub and Related Malacophyllous Shrublands of Other Mediterranean- California Wildlife Type Climates Conservation Bulletin No. 10 1994 Table of Contents: John F. O'Leary Department of Geography San Diego State Preface University San Diego, CA 92182- 1. Animals 4493 2. Autecology 3. Biogeography, Evolution, and Systematics Sandra A. DeSimone Department of Biology 4. Community Composition, Distribution, and San Diego State Classification University 5. Comparisons with Other Malacophyllous San Diego, CA 92182- Shrublands in Mediterranean Climates 0057 6. Conservation, Restoration, and Management 7. Fire, Diversity, and Succession Dennis D. Murphy Center for Conservation 8. Maps Biology 9. Mediterranean Systems (Malacophyllous Only) of Department of Other Regions Biological Sciences 10. Morphology, Phenology, and Physiology Stanford University 11. Mosaics: Coastal Sage Scrub/Chaparral or Stanford CA 94305 Grasslands Peter Brussard 12. Productivity and Nutrient Use Department of Biology 13. Soils and Water Resources University of Nevada Reno, NV 89557-0015 Michael S. Gilpin Department of Biology University of California, San Diego La Jolla, CA 92093 Reed F. Noss 7310 N.W. Acorn Ridge Drive Corvallis, OR 97330 Bibliography on Coastal Sage Scrub Shrublands Page 1 of 2 Preface Coastal sage scrub is often referred to as "soft chaparral" to differentiate it from "hard chaparral," the more widespread shrub community that generally occupies more mesic sites and higher elevations in cismontane California. Unlike evergreen, sclerophyllous chaparral, coastal sage scrub is characterized by malacophyllous subshrubs with leaves that abscise during summer drought and are replaced by fewer smaller leaves (Westman 1981, Gray and Schlesinger 1983). Sage scrub also contrasts with chaparral in its lower stature (0.5 - 1.5 meters vs. -

Lemonade Berry

Native Plants in the South Pasadena Nature Park - #1 Powerpoint Presentation and Photographs by Barbara Eisenstein, October 23, 2012 To identify plants use some of your senses (and your common sense): Look at: plant size and shape ۵ leaf size, shape, color, texture and arrangement ۵ flower types, color, arrangement ۵ Touch (with care): fuzzy or smooth leaves ۵ stiff or flexible stems ۵ Smell: Many California plants have very distinctive odors especially in their leaves ۵ Some weeds are easily distinguished from natives by their smell ۵ Taste: !!!Never taste a plant you are unsure of. Some plants are poisonous ۵ Listen: .Rustling leaves can be hint ۵ NATIVE TREES AND LARGE SHRUBS • Coast live oak • Sugar bush • Engelmann oak • Laurel sumac • So. CA black walnut • Lemonade berry • Western sycamore • Yellow willow • Blue elderberry • Holly-leaf cherry • Toyon NATIVE Coast Live Oak (Quercus agrifolia) • Key Identifying Traits: Broad, evergreen oak tree with dark green leaves. Leaves cupped, green above, usually lighter beneath, with spines on margin Trunk is massive with gray bark. Tree, height: up to 30’, width: 35’ • Other facts: Magnificent native tree. Resistant to many pests and diseases but susceptible to oak root fungus (Armillaria mellea). To protect from root fungus, water established trees infrequently but deeply and avoid summer water. • May be confused with: Other oaks. Cupped leaves with spiny margins distinguish this oak. Bark is often smooth gray but in mature trees can be rough and variable. NATIVE Engelmann oak (Quercus engelmannii) • Key Identifying Traits: Drought deciduous tree, height: rarely taller than 40 ft., width: mature tree broader than tall. -

Santa Barbara Organics

Santa Loren Luyendyk, Owner 805-452-8249 [email protected] Barbara www.sborganics.com ISA Certified Arborist # WE 7805A Organics Licensed Nursery A13999.001 Certified Permaculture Design RegenTREES: for SoCal Criteria- edible, useful, n-fixing, habitat forming, locally adapted Native Nitrogen Fixers: Trees and large shrubs: • Acacia, Cat’s Claw (Acacia greggii) medicinal, bee forage • Alder (Alnus cordata) fast growing, windbreak, riparian, bee forage • California Lilac (Ceanothus spp.) bee forage • Chaparral Pea (Pickeringia montana), bee forage, low growing • Coffeeberry (Rhamnus californica) bee forage • False Indigo (Amorpha fruticosa) • Ironwood (Olneya tesota) wood, bee forage, windbreak • Mesquite (Prosopis spp.) • Mesquite, Honeypod (Prosopis glandulosa) edible pods, animal forage, bee forage, wood • Mountain Mahogany (Cercocarpus montanus) slow growing • Palo Verde (Cercidium floridum ,C. microphyllum) • Redbud, Western (Cercis occidentalis) edible flowers, bee forage • Smoke Tree (Psorothamnus spinosus) Shrubs and Herbs: • Buffalo Berry (Shepherdia canadensis) fair fruit • Chaparral Pea (Pickeringia) • Clover (Trifolium spp.) • Deer Vetch (Lotus crassifolius) bee forage • Deer Weed (Lotus scoparius) bee forage • Fairy Duster (Calliandra eriophylla) • Indigo Bush (Dale sp.) • Leather Root (Hoita syn. Psoralea orbicularis) • Locoweed (Astragalus nuttallii) • Lupine (Lupinus spp.) • Lupine (Lupinus spp.) bee forage • Marina (Marina parryi) • Milk Vetch (Astragalus sp.) medicinal, bee forage Non-Native Nitrogen Fixers: Trees -

Schinus Terebinthifolius

Schinus terebinthifolius INTRODUCTORY DISTRIBUTION AND OCCURRENCE BOTANICAL AND ECOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS FIRE EFFECTS AND MANAGEMENT MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS APPENDIX: FIRE REGIME TABLE REFERENCES INTRODUCTORY AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION FEIS ABBREVIATION NRCS PLANT CODE COMMON NAMES TAXONOMY SYNONYMS LIFE FORM Photo by Shirley Denton, Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION: Meyer, Rachelle. 2011. Schinus terebinthifolius. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [ 2011, February 25]. FEIS ABBREVIATION: SCHTER NRCS PLANT CODE [190]: SCTE COMMON NAMES: Brazilian pepper Brazilian peppertree Christmas berry Florida holly aroeira TAXONOMY: The scientific name for Brazilian pepper is Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi (Anacardiaceae) [12,94,95,190]. The following varieties are recognized: Schinus terebinthifoliusvar. terebinthifolius Raddi [12,95] Schinus terebinthifolius var. raddianus Engl. [12,94,95] Schinus terebinthifolius var. acutifolius Engl Schinus terebinthifolius var. pohlianus Engl. [12] Schinus terebinthifolius var. rhoifoliusEngl. [12,94] SYNONYMS: None LIFE FORM: Shrub-tree DISTRIBUTION AND OCCURRENCE SPECIES: Schinus terebinthifolius GENERAL DISTRIBUTION HABITAT TYPES AND PLANT COMMUNITIES Photo by Vic Ramey, University of Florida, IFAS-Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants GENERAL DISTRIBUTION: A native to Brazil, Argentina, and Paraguay [24,56,70], Brazilian pepper has established in many areas outside its native range, such as Australia [13,199], South Africa [83,137,199], Mediterranean Europe, southern Asia, and the United States [137,199], including Puerto Rico [56,188]. Although Brazilian pepper was introduced to the United States as an ornamental from the mid- to late 1800s [7,56,119,137,211], it did not establish outside of cultivation in Florida until the 1950s [3,56]. -

Thirteen Plant Taxa from the Northern Channel Islands Recovery Plan

Thirteen Plant Taxa from the Northern Channel Islands Recovery Plan I2 cm Illustration of island barberry (Berberis pinnata ssp. insularis). Copyright by the Regents of the University of California, reproduced with permission of the Jepson Herbarium, University of California. THIRTEEN PLANT TAXA FROM THE NORTHERN CHANNEL ISLANDS RECOVERY PLAN Region 1 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Portland, Oregon Approved: Operations Office, Wildlife Service Date: I PRIMARY AUTHOR The Recovery Plan for Thirteen Plant Taxa from the Northern Channel Islands was prepared by: Tim Thomas U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1 DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions which are believed to be required to recover and/or protect listed species. We (the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) publish recovery plans, sometimes preparing them with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, State agencies, and others. Objectives of the recovery plan will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Costs indicated for task implementation and/or time for achievement ofrecovery are only estimates and are subject to change. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views, official positions, or approval ofany individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation other than our own. They represent our official position only after they have been signed by the Director, Regional Director, or CalifornialNevada Operations Office Manager as approved. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery tasks. Literature citation should read: U.S. -

Plastid Genomes of the North American Rhus Integrifolia-Ovata Complex and Phylogenomic Implications of Inverted Repeat Structural Evolution in Rhus L

Plastid genomes of the North American Rhus integrifolia-ovata complex and phylogenomic implications of inverted repeat structural evolution in Rhus L. Craig F. Barrett Department of Biology, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV, USA ABSTRACT Plastid genomes (plastomes) represent rich sources of information for phylogenomics, from higher-level studies to below the species level. The genus Rhus (sumac) has received a significant amount of study from phylogenetic and biogeographic perspectives, but genomic studies in this genus are lacking. Rhus integrifolia and R. ovata are two shrubby species of high ecological importance in the southwestern USA and Mexico, where they occupy coastal scrub and chaparral habitats. They hybridize frequently, representing a fascinating system in which to investigate the opposing effects of hybridization and divergent selection, yet are poorly characterized from a genomic perspective. In this study, complete plastid genomes were sequenced for one accession of R. integrifolia and one each of R. ovata from California and Arizona. Sequence variation among these three accessions was characterized, and PCR primers potentially useful in phylogeographic studies were designed. Phylogenomic analyses were conducted based on a robustly supported phylogenetic framework based on 52 complete plastomes across the order Sapindales. Repeat content, rather than the size of the inverted repeat, had a stronger relative association with total plastome length across Sapindales when analyzed with phylogenetic least squares regression. Variation at the inverted repeat boundary within Rhus was striking, resulting in major shifts and independent gene losses. 10 February 2020 Submitted Specifically, rps19 was lost independently in the R. integrifolia-ovata complex and in Accepted 17 May 2020 Published 16 June 2020 R. -

Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area Vascular Plant

Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area Vascular Plant Species List (as derived from NPSpecies 18 Dec 2006) FAMILY NAME Scientific Name (Common Name) (* = non-native) - [Abundance] ASPLENIACEAE AIZOACEAE Asplenium vespertinum (spleenwort) - [Rare] Carpobrotus edulis (hottentot-fig) * - [Common] Galenia pubescens * - [Rare] AZOLLACEAE Malephora crocea * - [Uncommon] Azolla filiculoides (duck fern, mosquito fern) - [Rare] Mesembryanthemum crystallinum (common ice plant) * - [Common] BLECHNACEAE Mesembryanthemum nodiflorum (slender-leaved ice plant) * Woodwardia fimbriata (chain fern) - [Uncommon] - [Uncommon] DENNSTAEDTIACEAE Tetragonia tetragonioides (New Zealand-spinach) * - Pteridium aquilinum var. pubescens (western bracken) - [Uncommon] [Uncommon] AMARANTHACEAE DRYOPTERIDACEAE Amaranthus albus (tumbleweed) - [Common] Dryopteris arguta (coastal woodfern) - [Common] Amaranthus blitoides (prostrate pigweed) * - [Common] Amaranthus californicus (California amaranth) - [Uncommon] EQUISETACEAE Amaranthus deflexus (low amaranth) * - [Uncommon] Equisetum arvense - [Uncommon] Amaranthus powellii - [Unknown] Equisetum hyemale ssp. affine (common scouring rush) - Amaranthus retroflexus (rough pigweed) * - [Common] [Uncommon] Equisetum laevigatum (smooth scouring-rush) - [Uncommon] ANACARDIACEAE Equisetum telmateia ssp. braunii (giant horsetail) - Malosma laurina (laurel sumac) - [Common] [Uncommon] Rhus integrifolia (lemonadeberry) - [Common] Equisetum X ferrissi ((sterile hybrid)) - [Unknown] Rhus ovata (sugar