{PDF EPUB} the Existential Joss Whedon Evil and Human Freedom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Girl in the Woods: on Fairy Stories and the Virgin Horror

Journal of Tolkien Research Volume 10 Issue 1 J.R.R. Tolkien and the works of Joss Article 3 Whedon 2020 The Girl in the Woods: On Fairy Stories and the Virgin Horror Brendan Anderson University of Vermont, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch Recommended Citation Anderson, Brendan (2020) "The Girl in the Woods: On Fairy Stories and the Virgin Horror," Journal of Tolkien Research: Vol. 10 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch/vol10/iss1/3 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Christopher Center Library at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Tolkien Research by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Anderson: The Girl in the Woods THE GIRL IN THE WOODS: ON FAIRY STORIES AND THE VIRGIN HORROR INTRODUCTION The story is an old one: the maiden, venturing out her door, ignores her guardian’s prohibitions and leaves the chosen path. Fancy draws her on. She picks the flow- ers. She revels in her freedom, in the joy of being young. Then peril appears—a wolf, a monster, something with teeth for gobbling little girls—and she learns, too late, there is more to life than flowers. The girl is destroyed, but then—if she is lucky—she returns a woman. According to Maria Tatar (while quoting Catherine Orenstein): “the girl in the woods embodies ‘complex and fundamental human concerns’” (146), a state- ment at least partly supported by its appearance in the works of both Joss Whedon and J.R.R. -

How Disney Visual Media Influences Children's Perceptions of Family a Content Analysis an Honors Thesis

Family on Film: How Disney Visual Media Influences Children's Perceptions of Family A Content Analysis An Honors Thesis (SOC 424) by Alexandra Garman Thesis Advisor Dr. Richard Petts ) c' __ / Ball State University Muncie, Indiana December, 2011 Expected Date of Graduation December 17, 2011 ," I . / ' 1 Abstract The Walt Disney Company has held a decades-long grip on family entertainment through visual media, amusement parks, clothing, toys, and even food. American children, and children throughout the world, are readily exposed to Disney's visual media as often as several times a day through film and television shows. As such, reviewing what this media says and analyzing its potential affects on our society can be beneficial in determining what messages children are receiving regarding values and norms concerning family. Specifically, analyzing family structure can help to provide an outlook for future normative structure. Depicted family interactions may also reflect how realistic families interact, what children expect from their families, and how children may interact with their own families in coming years. This study seeks to analyze various media released in recent years (2006-2011) and how these media portray family structure and interaction. Family appears to be variant in structure, including varied parental figures, as well as occasionally including non-biological figures. However, the family structure still seems, on the whole, to fit or otherwise promote (through inability of variants to do well) the traditional family model ofheterosexual, married biological parents and their offspring. Interestingly, Disney appears to place a great emphasis on fathers. Interactions between family members are relatively balanced, with some families being more positive in interaction and others being more negative. -

GARRET DONNELLY EDITOR TELEVISION PAINKILLER (Limited Series) Netflix Prod: Eric Newman, Micah Fitzerman-Blue Dir: Peter Berg Noah Harpster

GARRET DONNELLY EDITOR TELEVISION PAINKILLER (Limited Series) Netflix Prod: Eric Newman, Micah Fitzerman-Blue Dir: Peter Berg Noah Harpster NARCOS: MEXICO (Season 1-3) Netflix Prod: Eric Newman, Tim King Dir: Josef Kubota Wladyka Amat Escalante Andres Baiz NOS4A2 (Season 2) AMC Prod: Jami O’Brien Dir: Craig William MacNeill KNIGHTFALL (Season 2) The History Channel Prod: Aaron Helbing, Josh Appelbaum Dir: Rick Jacobson Andre Nemic, Jeff Pickner David Wellington Scott Rosenberg HEATHERS (Season 1) Paramount Network Prod: Jason Micallef, Tom Rosenberg Dir: Adam Silver Gary Lucchesi, Annie Mebane Jessica Lowrey Keith Raskin THE NIGHT SHIFT (Season 4) Sony TV/NBC Prod: Jeff Judah, Gabe Sachs, Tom Garrigus Dir: Various 24: LEGACY (Season 1) 20th Century Fox/FOX Prod: Evan Katz, Manny Coto, Jon Cassar Dir: Nelson McCormick Howard Gordon, Stephen Hopkins Jon Cassar TYRANT (Seasons 2-3) 20th Century Fox/FX Prod: Chris Keyser, Howard Gordon Dir: Various Glenn Gordon Caron, David Fury SECOND CHANCE (Season 1) 20th Century Fox/FOX Prod: Rand Ravich, Donald Todd Dir: Various Howard Gordon, Brad Turner HOMELAND (Episodes 401, 412) Fox 21/Showtime Prod: Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon Dir: Lesli Linka Glatter RAY DONOVAN (Episode 204) Showtime Prod: Ann Biderman Dir: Tucker Gates ASSISTANT EDITOR (TELEVISION) PROOF (Season 1) TNT Productions/TNT Prod: Rob Bragin, Jessica Grasi, Rose Lam Dir: Allison Anders HOMELAND (Seasons 1-4) Fox 21/Showtime Prod: Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon Dir: Various RAY DONOVAN (Pilot, Seasons 1-2) Showtime Prod: Ann Biderman Dir: Allen Coulter (P) Various THE KILLING (Season 2) Fox 21/AMC Prod: Veena Sud Dir: Various CHAOS (Season 1) 20th Century Fox/CBS Prod: Tom Spezialy Dir: Various MEDIUM (Seasons 3-7) CBS Studios/NBC Prod: Glenn Gordon Caron Dir: Various FEATURES BROKEN BOY SOLDIER (Short) Burnside Entertainment Prod: Seth William Meier Dir: Travis Donnelly 405 S Beverly Drive, Beverly Hills, California 90212 - T 310.888.4200 - F 310.888.4242 www.apa-agency.com . -

A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected]

Student Research and Creative Works Book Collecting Contest Essays University of Puget Sound Year 2015 The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected] This paper is posted at Sound Ideas. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/book collecting essays/6 Krista Silva The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works I am an inhabitant of the Whedonverse. When I say this, I don’t just mean that I am a fan of Joss Whedon. I am sincere. I live and breathe his works, the ever-expanding universe— sometimes funny, sometimes scary, and often heartbreaking—that he has created. A multi- talented writer, director and creator, Joss is responsible for television series such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer , Firefly , Angel , and Dollhouse . In 2012 he collaborated with Drew Goddard, writer for Buffy and Angel , to bring us the satirical horror film The Cabin in the Woods . Most recently he has been integrated into the Marvel cinematic universe as the director of The Avengers franchise, as well as earning a creative credit for Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. My love for Joss Whedon began in 1998. I was only eleven years old, and through an incredible moment of happenstance, and a bit of boredom, I turned the television channel to the WB and encountered my first episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer . I was instantly smitten with Buffy Summers. She defied the rules and regulations of my conservative southern upbringing. -

The Retriever, Issue 1, Volume 39

18 Features August 31, 2004 THE RETRIEVER Alien vs. Predator: as usual, humans screwed it up Courtesy of 20th Century Fox DOUGLAS MILLER After some groundbreaking discoveries on Retriever Weekly Editorial Staff the part of the humans, three Predators show up and it is revealed that the temple functions as prov- Many of the staple genre franchises that chil- ing ground for young Predator warriors. As the dren of the 1980’s grew up with like Nightmare on first alien warriors are born, chaos ensues – with Elm street or Halloween are now over twenty years Weyland’s team stuck right in the middle. Of old and are beginning to loose appeal, both with course, lots of people and monsters die. their original audience and the next generation of Observant fans will notice that Anderson’s filmgoers. One technique Hollywood has been story is very similar his own Resident Evil, but it exploiting recently to breath life into dying fran- works much better here. His premise is actually chises is to combine the keystone character from sort of interesting – especially ideas like Predator one’s with another’s – usually ending up with a involvement in our own development. Anderson “versus” film. Freddy vs. Jason was the first, and tries to allow his story to unfold and build in the now we have Alien vs. Predator, which certainly style of Alien, withholding the monsters almost will not be the last. Already, the studios have toyed altogether until the second half of the film. This around with making Superman vs. Batman, does not exactly work. -

Jun 18 Customer Order Form

#369 | JUN19 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE JUN 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Jun19 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:08:57 PM June19 Humanoids Ad.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:15:02 PM SPAWN #300 MARVEL ACTION: IMAGE COMICS CAPTAIN MARVEL #1 IDW PUBLISHING BATMAN/SUPERMAN #1 DC COMICS COFFIN BOUND #1 GLOW VERSUS IMAGE COMICS THE STAR PRIMAS TP IDW PUBLISHING BATMAN VS. RA’S AL GHUL #1 DC COMICS BERSERKER UNBOUND #1 DARK HORSE COMICS THE DEATH-DEFYING DEVIL #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT MARVEL COMICS #1000 MARVEL COMICS HELLBOY AND THE B.P.R.D.: SATURN RETURNS #1 ONCE & FUTURE #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BOOM! STUDIOS Jun19 Gem Page.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:24:56 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Bad Reception #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS The Flash: Crossover Crisis Book 1: Green Arrow’s Perfect Shot HC l AMULET BOOKS Archie: The Married Life 10 Years Later #1 l ARCHIE COMICS Warrior Nun: Dora #1 l AVATAR PRESS INC Star Wars: Rey and Pals HC l CHRONICLE BOOKS 1 Lady Death Masterpieces: The Art of Lady Death HC l COFFIN COMICS 1 Oswald the Lucky Rabbit: The Search for the Lost Disney Cartoons l DISNEY EDITIONS Moomin: The Lars Jansson Edition Deluxe Slipcase l DRAWN & QUARTERLY The Poe Clan Volume 1 HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Cycle of the Werewolf SC l GALLERY 13 Ranx HC l HEAVY METAL MAGAZINE Superman and Wonder Woman With Collectibles HC l HERO COLLECTOR Omni #1 l HUMANOIDS The Black Mage GN l ONI PRESS The Rot Volume 1 TP l SOURCE POINT PRESS Snowpiercer Hc Vol 04 Extinction l TITAN COMICS Lenore #1 l TITAN COMICS Disney’s The Lion King: The Official Movie Special l TITAN COMICS The Art and Making of The Expance HC l TITAN BOOKS Doctor Mirage #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT The Mall #1 l VAULT COMICS MANGA 2 2 World’s End Harem: Fantasia Volume 1 GN l GHOST SHIP My Hero Academia Smash! Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA Kingdom Hearts: Re:Coded SC l YEN ON Overlord a la Carte Volume 1 GN l YEN PRESS Arifureta: Commonplace to the World’s Strongest Zero Vol. -

Joss Whedon Versus the Corporation : Big Business Critiqued in the Films and Television Programs

JOSS WHEDON VERSUS THE CORPORATION : BIG BUSINESS CRITIQUED IN THE FILMS AND TELEVISION PROGRAMS Author: Erin Giannini Number of Pages: 223 pages Published Date: 30 Jan 2018 Publisher: McFarland & Co Inc Publication Country: Jefferson, NC, United States Language: English ISBN: 9781476667768 DOWNLOAD: JOSS WHEDON VERSUS THE CORPORATION : BIG BUSINESS CRITIQUED IN THE FILMS AND TELEVISION PROGRAMS Joss Whedon Versus the Corporation : Big Business Critiqued in the Films and Television Programs PDF Book about the author: Dr. Martha Chesler, 54, lost 11 pounds. " So begins Deirdre Chetham's elegiac book about the towns along the banks of the Three Gorges area of the Yangtze River, written on the very eve of their destruction. Opler's classic Culture, Psychiatry, and Human Values has here been revised and expanded to nearly twice the size of the original work. Digital Photography For DummiesA new edition gets you in the picture for learning digital photography Whether you have a point-and-shoot or digital SLR camera, this new edition of the full-color bestseller is packed with tips, advice, and insight that you won't find in your camera manual. In The Art of Woo, they present their systematic, four- step process for winning over even the toughest bosses and most skeptical colleagues. An Introduction to Language and Linguistics: Breaking the Language SpellChristopher Hall's book is the best new introduction to linguistics that I have seen in decades. Learn How to Get a Job and Succeed as a -CARGO SHIP CAPTAIN- Find out the secrets of scoring YOUr dream job. ' Paul Ernest, Emeritus Professor of Mathematics Education, University of Exeter Teaching mathematics can be challenging, and returning to a mathematics classroom yourself may not inspire you with confidence. -

Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic

Please do not remove this page Giving Evil a Name: Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic Croft, Janet Brennan https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643454990004646?l#13643522530004646 Croft, J. B. (2015). Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic. Slayage: The Journal of the Joss Whedon Studies Association, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.7282/T3FF3V1J This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/10/02 09:39:58 -0400 Janet Brennan Croft1 Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic “It’s about power. Who’s got it. Who knows how to use it.” (“Lessons” 7.1) “I would suggest, then, that the monsters are not an inexplicable blunder of taste; they are essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem …” (J.R.R. Tolkien, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”) Introduction: Names and Blood in the Buffyverse [1] In Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) and Angel (1999- 2004), words are not something to be taken lightly. A word read out of place can set a book on fire (“Superstar” 4.17) or send a person to a hell dimension (“Belonging” A2.19); a poorly performed spell can turn mortal enemies into soppy lovebirds (“Something Blue” 4.9); a word in a prophecy might mean “to live” or “to die” or both (“To Shanshu in L.A.” A1.22). -

Alyson Hannigan Listing by Ren Smith Featured in USA Today

Alyson Hannigan listing by Ren Smith featured in USA Today February 14, 2018 Alyson Hannigan has a genius way of keeping organized at home Alyson Hannigan is giving us serious inspiration. Having trouble keeping your family’s schedule organized? Steal this fun DIY idea from actress Alyson Hannigan. The “How I Met Your Mother” star recently put her Santa Monica, California house up for sale, and we noticed a large chalkboard calendar on one of the walls in the kitchen area. It made us immediately want to grab a bucket of chalkboard paintand some wood to create one like it in our own homes. The wall features five rows of seven squares separated by narrow strips of wood. Along the top of the larger frame that surrounds the calendar are the names of the days of the week. Each box can be numbered with chalk according to the current month. It’s the perfect place to write down appointment reminders, your kids’ sports practice schedules and even menu plans for the week. And when you want to keep track of miscellaneous things — such as future vacation countdowns, phone numbers, or notes to family members — there’s a larger square on the side for that. The wall can easily be re-created with a few supplies from a home improvement store, and there are also so many variations you can do, such as using whiteboard paint as the base or creating the frame and boxes with Washi tape if you don’t want to work with wood. Hannigan, who has two young daughters, told People in 2016 that she loves to craft so much, she turned her guest house into a crafting room. -

Batman, Screen Adaptation and Chaos - What the Archive Tells Us

This is a repository copy of Batman, screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/94705/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Lyons, GF (2016) Batman, screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us. Journal of Screenwriting, 7 (1). pp. 45-63. ISSN 1759-7137 https://doi.org/10.1386/josc.7.1.45_1 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Batman: screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us KEYWORDS Batman screen adaptation script development Warren Skaaren Sam Hamm Tim Burton ABSTRACT W B launch the Caped Crusader into his own blockbuster movie franchise were infamously fraught and turbulent. It took more than ten years of screenplay development, involving numerous writers, producers and executives, before Batman (1989) T B E tinued to rage over the material, and redrafting carried on throughout the shoot. -

The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 2010 "Just a Girl": The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007 Tamy Burnett University of Nebraska at Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Burnett, Tamy, ""Just a Girl": The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007" (2010). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 27. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. “JUST A GIRL”: THE COMMUNITY-CENTERED CULT TELEVISION HEROINE, 1995-2007 by Tamy Burnett A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English (Specialization: Women‟s and Gender Studies) Under the Supervision of Professor Kwakiutl L. Dreher Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2010 “JUST A GIRL”: THE COMMUNITY-CENTERED CULT TELEVISION HEROINE, 1995-2007 Tamy Burnett, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2010 Adviser: Kwakiutl L. Dreher Found in the most recent group of cult heroines on television, community- centered cult heroines share two key characteristics. The first is their youth and the related coming-of-age narratives that result. -

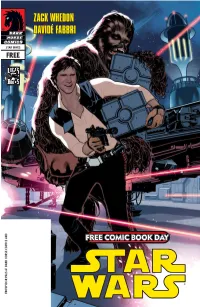

Zack Whedon Davidé Fabbri Zack Whedon 2/17/12 1:11 Pm ® S R

ZACKZACK WHEDONWHEDON ® DAVIDÉDAVIDÉ FABBRIFABBRI STAR WARS FREE ® FROM YOUR PALS AT DARK HORSE COMICS AND COMICS HORSE DARK AT PALS YOUR FROM FCBD12 SW-SEREN.indd 1 2/17/12 1:11 PM FCBD12 SW-SEREN.indd 2 tions, or locales, without satiric intent, is coincidental. Printed by Cadmus Communications, Easton, PA, U.S.A. tions, orlocales,without satiricintent,iscoincidental.Printed byCadmusCommunications,Easton, PA, Anyresemblancetoactual persons(livingordead),events,institu either aretheproduct oftheauthor’simaginationorareused fictitiously. writtenpermissionofDarkHorse Comics,Inc.Names,characters,places,andincidentsfeaturedinthispublication without theexpress categories andcountries.Allrightsreserved. Noportionofthispublicationmaybereproducedortransmitted,inanyform or are ©2012LucasfilmLtd.DarkHorse Comics® andtheDarkHorselogoaretrademarksofComics,Inc.,registered inva Wars andillustrationsforStar Text ©2012LucasfilmLtd.&™.Allrightsreserved.Usedunderauthorization. Milwaukie, OR97222.StarWars ArtoftheBadDeal,”May2012.PublishedbyDarkHorseComics, Inc.,10956SEMainStreet, WARS—“The STAR FREE COMICBOOK DAY: RONDA D MICHAEL A D ZACK WHEDON ZACK advertising sales: (503) 905-2370 » comic shop locator service: (888)266-4226 service: (503)905-2370»comicshop locator sales: advertising ALLA ALLA DA AVIDÉ FABBRI AVIDÉ MIKE RANDY RANDY M H M C assistant editor assistant collection editor P F HRISTIAN REDD cover art SIERRA R lettering V T ATTISON T ICHARDSON INA ALESSI ECCHIA talk about this issue online at: online at: aboutthisissue talk Pencils HO UGHES Colors STRADLE publisher D script designer YE YE AVID M editor Inks HAHN LINS AS Y STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS ANDERMAN at lucas licensing. ANDERMAN at ALDERS, CAROL special thankstoJ ROEDER Comics! Horse Dark from pals this your at free offering enjoy please afirst-timer, or time reader along you’re whether But Emperor.