Indigenous History and Treaty Lands in Dufferin County a Resource Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DUFFERIN COUNTY ROAD 2 ROAD RESURFACING and SELECT CULVERT Dufferin REPLACEMENT County CONTRACT NO

DUFFERIN COUNTY ROAD 2 ROAD RESURFACING AND SELECT CULVERT Dufferin REPLACEMENT county CONTRACT NO. TS-08-20 PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT ISSUED FOR TENDER ENGINEERING SERVICES LIST OF DRAWINGS COUNTY OF SIMCOE SITE LOCATION CLEARVIEW DRAWING LOCATION DESCRIPTION COUNTY OF GREY GREY HIGHLANDS COUNTY OF GREY GREY HIGHLANDS 2011-01 STA 0+000 TO 0+300 PLAN AND PROFILE 2011-02 STA 0+300 TO 0+600 PLAN AND PROFILE 2011-03 STA 0+600 TO 0+900 PLAN AND PROFILE TOWNSHIP TOWNSHIP 2011-04 STA 0+900 TO 1+200 PLAN AND PROFILE OF OF MELANCTHON MULMUR 2011-05 STA 1+200 TO 1+520 PLAN AND PROFILE 2011-06 STA 1+520 TO 1+800 PLAN AND PROFILE 2011-07 STA 1+800 TO 2+100 PLAN AND PROFILE SOUTHGATE COUNTY OF GREY TOWN OF ADJALA - TOSORONTIO 2031-08 STA 2+100 TO 2+400 PLAN AND PROFILE SHELBURNE COUNTY OF SIMCOE 2031-09 STA 2+400 TO 2+700 PLAN AND PROFILE 2032-10 STA 2+700 TO 3+000 PLAN AND PROFILE TOWN OF MONO DET-11 DETAILS-1 DETAILS DET-12 DETAILS-2 DETAILS TOWNSHIP OF AMARANTH DET-13 DETAILS-3 DETAILS TOWN OF GRAND VALLEY WELLINGTON NORTH COUNTY OF WELLINGTON GRAND VALLEY REGIONAL MUNICIPALITY OF PEEL TOWN OF CALEDON TOWN OF ORANGEVILLE COUNTY OF WELLINGTON CENTRE WELLINGTON DUFFERIN COUNTY ROAD 2 - ROAD RESURFACING AND SELECT CULVERT REPLACEMENT TOWNSHIP CONTRACT No. TS-08-20 - ISSUED FOR TENDER OF EAST GARAFRAXA LEGEND - DUFFERIN COUNTY ROAD ERIN PROVINCIAL HIGHWAY COUNTY OF WELLINGTON county Dufferin LEGEND: DUFFERIN COUNTY N EMG.#783129 EMG.#239188 ROAD 9 DUFFERIN COUNTY ROAD 2 EMG.#783129 4TH LINE MELANCTHON EMG.#239031 0 15 30 Meters NOTES: 532 532 531 531 -

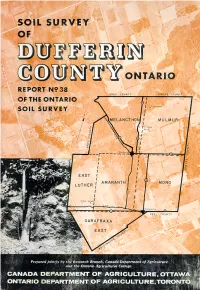

Key to Classification of Wellington County Soils 18 Dumfries Series

SOIL SURVEY of DUFFERIN COUNTY Ontario bY D. W. Hoffman B. C. Matthews Ontario Agricultural College R. E. Wicklund Soil Research Institute GUELPH, ONTARIO 1964 REPORT NO. 38 OF THE ONTARIO SOIL SURVEY RESEARCH BRANCH, CANADA DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE AND THE ONTARIO AGRICULTURAL COLLEGE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors wish to express their appreciation for the advice and assistance given by Dr. P. C. Stobbe, Director of the Soil Research Institute, Canada Depart- ment of Agriculture. The soil map was prepared for lithographing by the Cartographic section of the Soil Research Institute, Ottawa. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ,. .. ,,, 6 General Description of the Area ,, .. .. .. Location .._....... .. .. 2 Principal Towns . .. .. 6 Population . .. 6 Transportation .’ .. .. .. .,.... ..,. 8 Geology of the Unherlymg Rocks”: Surface Deposits \:..:1 “’ Fi Vegetation ,.. .. .. .. .. .. 12 Climate .. .. .. .. .. Relief and Drainage ,,,.. ,,,,“’ ,,. ,, ,,, :; The Classification and Description of the Soils 14 Series, Types, Phases and Complexes 16 Soil Catena __, ,,,,...,,__,.,,..,.._... _.,,...... ...l1..... ‘I 17 Key to Classification of Wellington County Soils 18 Dumfries Series . 20 Bondhead Series 11:” ” 2 1 Guelph Series . 22 London Series ” .’ Parkhill Series .... “’ 1: ‘1. : : ;; Harriston Series .’ 25 Harkaway Series 25 Listowel Series ., _, . ,, .,,, Wiarton Series ‘I ” ” 2 Huron Series Perth Series . iii Brookston Series ,’ ,. ,, 29 Dunedin Series Fox Series ,.., ,,...” ,, .: .. .. ,.,,,,, ;; Tioga Series 30 Brady Series Alliston Series 8 Granby Series 31 Burford Series ,, ,. ,. ., .. 1: 32 Brisbane Series 33 Gilford Series 1 ‘1’:. ‘.:I 33 Caledon Series ” . .. 33 Camilla Series 34 Hillsburgh Series ‘.I ” “” ,111.. ,, ” 34 Donnybrook Series 35 Bookton Series ,. .. .. .. 36 Wauseon Series ” ” Dundonald Series ,. “I’ ._ “1. i:: Honeywood Series 37 Embro Series 38 Crombie Series _... : .. 3 8 Bennington Series 38 Tavistock Series 1.1. -

The Route and Purpose of Champlain's Journey to the Petun in 1616

Document généré le 24 sept. 2021 08:18 Ontario History The Route and Purpose of Champlain’s Journey to the Petun in 1616 Charles Garrad Volume 107, numéro 2, fall 2015 Résumé de l'article Dans cet essai, nous revisitons l’expédition entreprise par Samuel de URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1050633ar Champlain, lors de laquelle il rencontra les Odawas, les Petuns, ainsi que des DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1050633ar délégations de Neutres qui se trouvaient dans la région. Tout en confirmant les conclusions déjà établies, nous émettons de nouvelles hypothèses sur les Aller au sommaire du numéro raisons pourquoi la poursuite de la route qui conduirait vers les Neutres et ensuite vers l’Orient n’a pas eu lieu.. Éditeur(s) The Ontario Historical Society ISSN 0030-2953 (imprimé) 2371-4654 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Garrad, C. (2015). The Route and Purpose of Champlain’s Journey to the Petun in 1616. Ontario History, 107(2), 159–178. https://doi.org/10.7202/1050633ar Copyright © The Ontario Historical Society, 2015 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. -

Rank of Pops

Table 1.3 Basic Pop Trends County by County Census 2001 - place names pop_1996 pop_2001 % diff rank order absolute 1996-01 Sorted by absolute pop growth on growth pop growth - Canada 28,846,761 30,007,094 1,160,333 4.0 - Ontario 10,753,573 11,410,046 656,473 6.1 - York Regional Municipality 1 592,445 729,254 136,809 23.1 - Peel Regional Municipality 2 852,526 988,948 136,422 16.0 - Toronto Division 3 2,385,421 2,481,494 96,073 4.0 - Ottawa Division 4 721,136 774,072 52,936 7.3 - Durham Regional Municipality 5 458,616 506,901 48,285 10.5 - Simcoe County 6 329,865 377,050 47,185 14.3 - Halton Regional Municipality 7 339,875 375,229 35,354 10.4 - Waterloo Regional Municipality 8 405,435 438,515 33,080 8.2 - Essex County 9 350,329 374,975 24,646 7.0 - Hamilton Division 10 467,799 490,268 22,469 4.8 - Wellington County 11 171,406 187,313 15,907 9.3 - Middlesex County 12 389,616 403,185 13,569 3.5 - Niagara Regional Municipality 13 403,504 410,574 7,070 1.8 - Dufferin County 14 45,657 51,013 5,356 11.7 - Brant County 15 114,564 118,485 3,921 3.4 - Northumberland County 16 74,437 77,497 3,060 4.1 - Lanark County 17 59,845 62,495 2,650 4.4 - Muskoka District Municipality 18 50,463 53,106 2,643 5.2 - Prescott and Russell United Counties 19 74,013 76,446 2,433 3.3 - Peterborough County 20 123,448 125,856 2,408 2.0 - Elgin County 21 79,159 81,553 2,394 3.0 - Frontenac County 22 136,365 138,606 2,241 1.6 - Oxford County 23 97,142 99,270 2,128 2.2 - Haldimand-Norfolk Regional Municipality 24 102,575 104,670 2,095 2.0 - Perth County 25 72,106 73,675 -

Electronic Council Agenda July 8, 2020 9:00Am

ELECTRONIC COUNCIL AGENDA JULY 8, 2020 9:00AM THIS MEETING IS BEING HELD ELECTRONICALLY USING VIDEO AND/OR AUDIO CONFERENCING, AND IS BEING RECORDED. To connect only by phone, please dial any of the following numbers. When prompted, please enter the meeting ID provided below the phone numbers. You will be placed into the meeting in muted mode. If you encounter difficulty, please call the front desk at 705-466-3341, ext. 0 +1 647 374 4685 Canada +1 647 558 0588 Canada +1 778 907 2071 Canada +1 438 809 7799 Canada +1 587 328 1099 Canada Meeting ID: 835 5340 4999 To connect to video with a computer, smart phone or digital device) and with either digital audio or separate phone line, download the zoom application ahead of time and enter the digital address below into your search engine or follow the link below. Enter the meeting ID when prompted. https://us02web.zoom.us/j/83553404999 Meeting ID: 835 5340 4999 1.1 Meeting called to order 1.2 Approval of the Agenda Staff recommendation: THAT Council approve the agenda. 6 1.3 Passing of the previous meeting minutes a) Regular Council Meeting – June 3, 2020 Minutes Staff recommendation: THAT the Minutes of June 3, 2020 are approved. b) Special Joint Council Meeting – June 3, 2020 – Minutes Staff recommendation: THAT the June 3, 2020 Minutes of the Special Joint Meeting of the Township of Mulmur and the Township of Melancthon are approved. 1.4 Declaration of Pecuniary Interest 1.5 Fifteen-minute question period (all questions must be submitted to the Clerk at [email protected], a minimum of 24 hours before the meeting date) 2.0 PUBLIC MEETINGS – none 3.0 DEPUTATIONS AND INVITATIONS 15 9:20 a.m. -

Transportation

TRANSPORTATION COMMUNITY TRANSPORTATION and TAXI SERVICE – Dufferin County Name Phone No Service Description Bayshore Home Health 905-277-3116 Transportation * wheelchair transportation 2100 Bovaird Dr E Brampton, ON, L6R 3J7 www.bayshore.ca Canadian Cancer Society 519-249-0074 Wheels of Hope Transportation Service covers 2 programs: Volunteer Driver Waterloo-Wellington Community 1-888-939-3333 Provided Program and Family Provided Program. These programs are intended Office to assist an eligible client and escort (if required) with their short-term travel 380 Jamieson Parkway, Unit 12 to attend cancer-specific medical appointments or supportive care services Cambridge, ON, N3C 4N4 delivered by a professional recognized by Ontario's Health Care System. Must www.cancer.ca declare a financial, physical or emotional need for service Volunteer driver provided program - provide return trips for patients from their home to treatment centres. New patients who register for volunteer driver provided transportation will be required to pay a one-time registration fee of $100. Patients 18 years or younger or are covered by the Northern Health Travel Grant are exempt. If you are unable to pay the full registration fee, you may be eligible for assistance through the compassionate program To register or for more information call 1-800-263-6750 Family provided program - assistance is available to a family whose child has cancer and is traveling 200 km (one way) or more to get to the treatment centre(s). In these instances families provide the transportation -

LIB-002-2019 (First Quarter Report 2019)

REPORT TO COUNCIL REPORT NUMBER: LIB-002-2019 DEPARTMENT: Clearview Public Library Board MEETING DATE: May 13, 2019 SUBJECT: First Quarter Report 2019 RECOMMENDATION: Be It Resolved, that Council of the Township of Clearview hereby: 1) Receives the Clearview Public Library Board First Quarter Report 2019. BACKGROUND: This report summarizes the activities of the Clearview Public Library in the first quarter of 2019. COMMENTS AND ANALYSIS: Building Project A revised schedule for the project has been distributed, and Bondfield is currently meeting the schedule targets. Programs Program attendance exceeded 2000 in each of these three months. Use of in- library computers, as well as wireless access through patron-owned devices, continue to be the Library’s most used program service. Pre-school programs provided through area schools are also very popular, with February being the busiest month in this period with 429 participants. Clearview Public Library’s Adult Colouring program, which provides participants an opportunity to socialize as well as to achieve mindfulness and reduce anxiety, has been running out of the Stayner Branch and area churches for a number of years. The program has developed a loyal following, but the participants have requested Page 1 of 5 that the program be moved permanently to the library for ease of access to the collection and services and so that there is no confusion about where the program will be held each week. Library staff have thanked the local churches who have generously partnered with us on this program for supporting it over the years. March Break programs included two VanGo programs provided by the MacLaren Art Gallery, as well as a wide variety of in-library programs for all ages geared to the STEM curriculum. -

Addressing Social Determinants of Health in Dufferin County a Public Health Perspective on Local Health, Policy and Program Needs

Addressing Social Determinants of Health in Dufferin County A public health perspective on local health, policy and program needs Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health ©Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health 2013 This report is available at www.wdgpublichealth.ca/reports For more information, please contact: Health Promotion and Health Analytics Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health 503 Imperial Rd N Guelph, ON N1H 6T9 T: 519-846-2715 or 1-800-265-7293 [email protected] www.wdgpublichealth.ca Terms of use Information in this report has been produced with the intent that it be readily available for personal or public non-commercial use and may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, without further permission. Users are required to: x Exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; and x Reference the report using the citation below, giving full acknowledgement to Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health. Citation Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health (2013). Addressing Social Determinants of Health in Dufferin County: A public health perspective on local health, policy, and program needs. Guelph, Ontario. Acknowledgements Authors Daniela Seskar-Hencic Laura Campbell, Health Promotion Specialist, Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health Keira Rainville, Masters of Public Health student, University of Guelph Louise Brooks, Health Promotion Specialist, Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health Primary Contributors Jennifer MacLeod, Program Manager, Health Analytics, Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health Wing Chan, Health Data Analyst, Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health Andrea Roberts, Director, Child & Family Health, Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health Sharlene Sedgwick Walsh, Director, Healthy Living, Planning & Promotion, Region of Waterloo Public Health 1 Acknowledgements | Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health Contents Acknowledgements........................................................................................................................ -

Dufferin County Greenhouse Gas Inventory

DUFFERIN COUNTY Community Greenhouse Gas Inventory ABOUT THE CLEAN AIR PARTNERSHIP: Clean Air Partnership (CAP) is a registered charity that works in partnership to promote and coordinate actions to improve local air quality and reduce greenhouse gases for healthy communities. Our applied research on municipal policies strives to broaden and improve access to public policy debate on air pollution and climate change issues. Clean Air Partnership’s mission is to transform cities into more sustainable, resilient, and vibrant communities where resources are used efficiently, the air is clean to breathe and greenhouse gas emissions are minimized. REPORT AUTHORS: Allie Ho, Clean Air Partnership Kevin Behan, Clean Air Partnership This initiative is offered through the Municipalities for Climate Innovation Program, which is delivered by the Federation of Canadian Municipalities and funded by the Government of Canada. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: This report represents the culmination of efforts invested by many parties who offered their policy and technical expertise to the research compiled in this report. We are grateful for the support of: Sara Wicks, Dufferin County TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 | INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 | CLIMATE CHANGE AND DUFFERIN COUNTY 2 1.2 | MILESTONE 1 2 2.0 | DATA SOURCES 3 3.0 | COMMUNITY GREENHOUSE GAS INVENTORY METHODOLOGY AND RESULTS 6 3.1 | RESIDENTIAL BUILDINGS 9 3.2 | COMMERCIAL BUILDINGS 15 3.3 | INDUSTRIAL BUILDINGS 17 3.4 | OTHER BUILDINGS 19 3.5 | TRANSPORTATION 21 3.6 | SOLID WASTE 24 3.7 | AGRICULTURE, FORESTRY AND OTHER LAND USE 26 4.0 | LOCAL MUNICIPALITIES WITHIN DUFFERIN COUNTY 30 5.0 | LIMITATIONS AND AREAS FOR IMPROVEMENT 31 5.1 | OTHER SOURCES OF ENERGY FOR RESIDENTIAL USE 31 5.2 | TRANSPORTATION 31 5.3 | SOLID WASTE 32 5.4 | AGRICULTURE, FORESTRY AND OTHER LAND USE 32 APPENDIX A | GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS FOR EACH LOCAL MUNICIPALITY 33 AMARANTH 34 EAST GARAFRAXA 35 GRAND VALLEY 36 MELANCTHON 37 MONO 38 MULMUR 39 ORANGEVILLE 40 SHELBURNE 41 INTRODUCTION 1.0 | INTRODUCTION Climate Change is one of the most urgent challenges facing humanity. -

Feasibility Study on a Potential Susquehanna Connector Trail for the John Smith Historic Trail

Feasibility Study on a Potential Susquehanna Connector Trail for the John Smith Historic Trail Prepared for The Friends of the John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail November 16, 2009 Coordinated by The Bucknell University Environmental Center’sNature and Human Communities Initiative The Susquehanna Colloquium for Nature and Human Communities The Susquehanna River Heartland Coalition for Environmental Studies In partnership with Bucknell University The Eastern Delaware Nations The Haudenosaunee Confederacy The Susquehanna Greenway Partnership Pennsylvania Environmental Council Funded by the Conservation Fund/R.K. Mellon Foundation 2 Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 3 Recommended Susquehanna River Connecting Trail................................................................. 5 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 6 Staff ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Criteria used for Study................................................................................................................. 6 2. Description of Study Area, Team Areas, and Smith Map Analysis ...................................... 8 a. Master Map of Sites and Trails from Smith Era in Study Area........................................... 8 b. Study -

Lecture Draft Notes (356.5Kb)

Surrender No. 40: draft 15 A Lecture/Performance Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Fine Arts (Special Case) in Theatre University of Regina By Kenneth Clayton Wilson 26 April 2017 © 2017: K.C. Wilson Acknowledgements Many people generously gave me advice and encouragement and assistance during the Muscle and Bone and Surrender No. 40 performances. I want to acknowledge their contributions here. In particular, I am grateful to Dr. Jesse Rae Archibald-Barber; Dr. Mary Blackstone; Professor Kathryn Bracht; Dr. Daniel Coleman; Dr. Edward Doolittle; Professor David Garneau; Norma General; Richard Goetze; Liz Goetze; Professor William Hales; Professor Kelly Handerek; Tom Hill; Dr. Andrew Houston; Dr. Kathleen Irwin; Naomi Johnson; Amos Key, Jr.; Rob Knox; Janice Longboat; Dr. Dawn Martin- Hill; Dr. Sophie McCall; Janis Monture; Professor Wes D. Pearce; Wendy Philpott; Jessica Powless; Dr. Brian Rice; Dr. Kathryn Ricketts; Dr. Dylan Robinson; Wanda Schmöckel; Michael Scholar, Jr.; Noel Starblanket; Ara Steininger; Dr. Michael Trussler; Bonnie Whitlow; Marilyn Wilson; Pamela Wilson McCormick; Maggie Wilson-Wong; Calvin Wong-Birss; and Dr. Tom Woodcock. I couldn’t have completed these performances without their help. Many others also helped out, and I am thankful for their assistance as well. The Department of English and the Lifelong Learning Centre, both at the University of Regina, and Dr. Kathryn Ricketts gave me opportunities to read the text before an audience, for which I am grateful. And, of course, I owe a tremendous debt of gratitude to Dr. Christine Ramsay for her continuing love, support, and encouragement. -

Huron-Wendat and Anthropological Perspectives

6 Ontario Archaeology No. 96, 2016 Understanding Ethnicity and Cultural Affiliation: Huron-Wendat and Anthropological Perspectives Mariane Gaudreau and Louis Lesage It is a well-known fact that archaeological cultures constructed by archaeologists do not always overlap with actual past ethnic groups. This is the case with the St. Lawrence Iroquoians of the Northeast. Up until re- cently, conventional narratives viewed this group as distinct from all other historic Iroquoian populations. However, the Huron-Wendat and the Mohawk consider themselves to be their direct descendants. Our paper is an attempt to reconcile oral history and archaeological interpretations by suggesting that part of the dis- parity between Huron-Wendat and archaeological conceptions of the group identity of the St. Lawrence Iro- quoians lies in differential understandings of the very nature of ethnicity by each party. Introduction For more than a century now, archaeologists have Indigenous peoples’ own conceptions of sought to establish correlates between material themselves and of their ancestors—or even with culture and ethnic groups (see Trigger 2006). ancient peoples’ conceptions of group identity, Unlike cultural anthropologists, who can access which sometimes contribute to alienate the emic perspectives on contemporary group communities from their past (e.g., Warburton and identity, archaeologists are often limited to Begay 2005; see also Voss 2015:659, 665). These extrapolating ethnicity from the material culture broader issues have engendered much discussion