History of the Business Development Bank of Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thursday, February 1, 2001

CANADA VOLUME 137 S NUMBER 004 S 1st SESSION S 37th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Thursday, February 1, 2001 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire'' at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 67 HOUSE OF COMMONS Thursday, February 1, 2001 The House met at 10 a.m. protection of employees in the public service who make allega- tions in good faith respecting wrongdoing in the public service. _______________ He said: Mr. Speaker, the purpose of the bill is to protect the Prayers members of the Public Service of Canada who blow the whistle in _______________ good faith for wrongdoing in the public service, such as reports of waste, fraud, corruption, abuse of authority, violation of law or D (1005 ) threats to public health or safety. The public interest is served when employees are free to make such reports without fear of retaliation [English] and discrimination. MESSAGE FROM THE SENATE Therefore, I am very pleased to introduce my private member’s The Speaker: I have the honour to inform the House that a bill, entitled an act respecting the protection of employees in the message has been received from the Senate informing this House public service who make allegations in good faith respecting that the Senate has passed certain bills, to which the concurrence of wrongdoing in the public service. this House is desired. (Motions deemed adopted, bill read the first time and printed) _____________________________________________ * * * ROUTINE PROCEEDINGS STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS ACT [Translation] Mr. -

The Requisites of Leadership in the Modern House of Commons 1

Number 4 November 2001 CANADIAN STUDY OF PARLIAMENT GROUP HE EQUISITES OF EADERSHIP THE REQUISITES OF LEADERSHIP IN THE MODERN HOUSE OF COMMONS Paper by: Cristine de Clercy Department of Political Studies University of Saskatchewan Canadian Members of the Study of Parliament Executive Committee Group 2000-2001 The Canadian Study of President Parliament Group (CSPG) was created Leo Doyle with the object of bringing together all those with an interest in parliamentary Vice-President institutions and the legislative F. Leslie Seidle process, to promote understanding and to contribute to their reform and Past President improvement. Judy Cedar-Wilson The constitution of the Canadian Treasurer Study of Parliament Group makes Antonine Campbell provision for various activities, including the organization of conferences and Secretary seminars in Ottawa and elsewhere in James R. Robertson Canada, the preparation of articles and various publications, the Counsellors establishment of workshops, the Dianne Brydon promotion and organization of public William Cross discussions on parliamentary affairs, David Docherty participation in public affairs programs Jeff Heynen on radio and television, and the Tranquillo Marrocco sponsorship of other educational Louis Massicotte activities. Charles Robert Jennifer Smith Membership is open to all those interested in Canadian legislative institutions. Applications for membership and additional information concerning the Group should be addressed to the Secretariat, Canadian Study of Parliament Group, Box 660, West Block, Ottawa, Ontario, K1A 0A6. Tel: (613) 943-1228, Fax: (613) 995- 5357. INTRODUCTION This is the fourth paper in the Canadian Study of Parliament Groups Parliamentary Perspectives. First launched in 1998, the perspective series is intended as a vehicle for distributing both studies prepared by academics and the reflections of others who have a particular interest in these themes. -

From Next Best to World Class: the People and Events That Have

FROM NEXT BEST TO WORLD CLASS The People and Events That Have Shaped the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation 1967–2017 C. Ian Kyer FROM NEXT BEST TO WORLD CLASS CDIC—Next Best to World Class.indb 1 02/10/2017 3:08:10 PM Other Historical Books by This Author A Thirty Years’ War: The Failed Public Private Partnership that Spurred the Creation of the Toronto Transit Commission, 1891–1921 (Osgoode Society and Irwin Law, Toronto, 2015) Lawyers, Families, and Businesses: A Social History of a Bay Street Law Firm, Faskens 1863–1963 (Osgoode Society and Irwin Law, Toronto, 2013) Damaging Winds: Rumours That Salieri Murdered Mozart Swirl in the Vienna of Beethoven and Schubert (historical novel published as an ebook through the National Arts Centre and the Canadian Opera Company, 2013) The Fiercest Debate: Cecil Wright, the Benchers, and Legal Education in Ontario, 1923–1957 (Osgoode Society and University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1987) with Jerome Bickenbach CDIC—Next Best to World Class.indb 2 02/10/2017 3:08:10 PM FROM NEXT BEST TO WORLD CLASS The People and Events That Have Shaped the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation 1967–2017 C. Ian Kyer CDIC—Next Best to World Class.indb 3 02/10/2017 3:08:10 PM Next Best to World Class: The People and Events That Have Shaped the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation, 1967–2017 © Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation (CDIC), 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

The Limits to Influence: the Club of Rome and Canada

THE LIMITS TO INFLUENCE: THE CLUB OF ROME AND CANADA, 1968 TO 1988 by JASON LEMOINE CHURCHILL A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2006 © Jason Lemoine Churchill, 2006 Declaration AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A THESIS I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This dissertation is about influence which is defined as the ability to move ideas forward within, and in some cases across, organizations. More specifically it is about an extraordinary organization called the Club of Rome (COR), who became advocates of the idea of greater use of systems analysis in the development of policy. The systems approach to policy required rational, holistic and long-range thinking. It was an approach that attracted the attention of Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. Commonality of interests and concerns united the disparate members of the COR and allowed that organization to develop an influential presence within Canada during Trudeau’s time in office from 1968 to 1984. The story of the COR in Canada is extended beyond the end of the Trudeau era to explain how the key elements that had allowed the organization and its Canadian Association (CACOR) to develop an influential presence quickly dissipated in the post- 1984 era. The key reasons for decline were time and circumstance as the COR/CACOR membership aged, contacts were lost, and there was a political paradigm shift that was antithetical to COR/CACOR ideas. -

Annual Report 2003 La De Annuel Rapport Rapport Annueldela 2003 Banque Ducanada

BANK OF CANADA OF CANADA BANK ANNUAL REPORT 2003 ANNUAL REPORT BANK OF CANADA ANNUAL REPORT 2003 2003 2003 BANQUE DU CANADA DU CANADA BANQUE BANQUE DU CANADA DU BANQUE LA DE ANNUEL RAPPORT RAPPORT ANNUEL DE LA RAPPORT Bank of Canada — 234 Wellington Street, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0G9 5211 — CN ISSN 0067-3587 ISSN CN — 5211 0G9 K1A Ontario Ottawa, Street, Wellington 234 — Canada of Bank his many volunteer activities. His warm wit and generous spirit will be sorely missed. sorely be will spirit generous and wit warm His activities. volunteer many his Gerry Bouey and neither will his community to which he contributed to the very end through end very the to contributed he which to community his will neither and Bouey Gerry Those who worked with him over the course of his long and remarkable career will never forget never will career remarkable and long his of course the over him with worked who Those Achievement Award. In 1987, he was made a Companion of the Order of Canada. of Order the of Companion a made was he 1987, In Award. Achievement of Laws from Queen’s University. In 1983, he was presented with the Outstanding Public Service Public Outstanding the with presented was he 1983, In University. Queen’s from Laws of In 1981, he was made an Officer of the Order of Canada and also received an Honorary Doctor Honorary an received also and Canada of Order the of Officer an made was he 1981, In economic development and to the Bank’s growing international reputation. -

Alternative North Americas: What Canada and The

ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS What Canada and the United States Can Learn from Each Other David T. Jones ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20004 Copyright © 2014 by David T. Jones All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of author’s rights. Published online. ISBN: 978-1-938027-36-9 DEDICATION Once more for Teresa The be and end of it all A Journey of Ten Thousand Years Begins with a Single Day (Forever Tandem) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Borders—Open Borders and Closing Threats .......................................... 12 Chapter 2 Unsettled Boundaries—That Not Yet Settled Border ................................ 24 Chapter 3 Arctic Sovereignty—Arctic Antics ............................................................. 45 Chapter 4 Immigrants and Refugees .........................................................................54 Chapter 5 Crime and (Lack of) Punishment .............................................................. 78 Chapter 6 Human Rights and Wrongs .................................................................... 102 Chapter 7 Language and Discord .......................................................................... -

Dalrev Vol44 Iss2 Pp165 171.Pdf (3.958Mb)

H. H. F. Binhammer CANADA'S MONEY MUDDLE IN RETROSPECT QUESTIONS CONCERNING THE CONTROL OF MONEY are as old as the use of money as a measure and store of value and a medium of exchange. Relevant to developments in the post~war period in Canada is the controversy of the mid-nineteenth century between the so-called Banking School and the Currency School. The Banking School maintained that control over the supply of money should be left in the hands of private commercial banks. The Currency School, on the other hand, among other things, maintained that control over the money supply should be vested directly or indirectly in the hands of government. Settlement in favour of the Currency School led to the establishment of central banks, mainly under the sponsorship of govern ments. These banks were to provide an umbrella over the private commercial banks. In Canada, interference with the money supply by a central authority started with the Finance Act of 1914. This was followed by the establishment of the Bank of Canada in 1935, first with limited government participation and later with com~ plete government control. The degree to which the central bank should assert its influence over the economy and in particular over the private commercial banks was not questioned until the fifties. During the thirties, the war, and the immediate post-war period, the central bank, on the whole, accommodated the activities of the chartered banks without question. That is to say, the central bank, in a more or less routine fashion, assisted the chartered banks to meet the demands of business. -

Tuesday, March 27, 2001

CANADA 1st SESSION · 37th PARLIAMENT · VOLUME 139 · NUMBER 20 OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Tuesday, March 27, 2001 THE HONOURABLE DAN HAYS SPEAKER CONTENTS (Daily index of proceedings appears at back of this issue.) Debates and Publications: Chambers Building, Room 943, Tel. 996-0193 Published by the Senate Available from Canada Communication Group — Publishing, Public Works and Government Services Canada, Ottawa K1A 0S9, Also available on the Internet: http://www.parl.gc.ca 438 THE SENATE Tuesday, March 27, 2001 The Senate met at 2 p.m., the Speaker in the Chair. champions. With one more step to climb, albeit a steep one, their dream of a world championship became a reality Saturday night Prayers. in Ogden, Utah. With Islanders in the stands and hundreds of others watching on television at the Silver Fox Curling Club in Summerside, SENATORS’ STATEMENTS these young women put on a show that was at once both inspiring and chilling. It was certainly a nervous time for everyone because those of us who have been watching all week QUESTION OF PRIVILEGE knew that the team Canada was playing in the finals was not only the defending world champion but the same team that had UNEQUAL TREATMENT OF SENATORS—NOTICE defeated Canada earlier in the week during the round robin. With steely determination, the young Canadian team overcame that The Hon. the Speaker: Honourable senators, I wish to inform mental obstacle and earned the world championship in the you that, in accordance with rule 43(3) of the Rules of the Senate, process. the Clerk of the Senate received, at 10:52 this morning, written notice of a question of privilege by the Honourable Senator The welcome the Canadian team received last night on their Carney, P.C. -

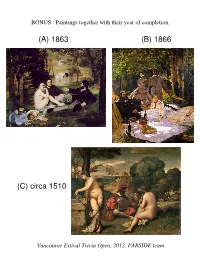

1866 (C) Circa 1510 (A) 1863

BONUS : Paintings together with their year of completion. (A) 1863 (B) 1866 (C) circa 1510 Vancouver Estival Trivia Open, 2012, FARSIDE team BONUS : Federal cabinet ministers, 1940 to 1990 (A) (B) (C) (D) Norman Rogers James Ralston Ernest Lapointe Joseph-Enoil Michaud James Ralston Mackenzie King James Ilsley Louis St. Laurent 1940s Andrew McNaughton 1940s Douglas Abbott Louis St. Laurent James Ilsley Louis St. Laurent Brooke Claxton Douglas Abbott Lester Pearson Stuart Garson 1950s 1950s Ralph Campney Walter Harris John Diefenbaker George Pearkes Sidney Smith Davie Fulton Donald Fleming Douglas Harkness Howard Green Donald Fleming George Nowlan Gordon Churchill Lionel Chevrier Guy Favreau Walter Gordon 1960s Paul Hellyer 1960s Paul Martin Lucien Cardin Mitchell Sharp Pierre Trudeau Leo Cadieux John Turner Edgar Benson Donald Macdonald Mitchell Sharp Edgar Benson Otto Lang John Turner James Richardson 1970s Allan MacEachen 1970s Ron Basford Donald Macdonald Don Jamieson Barney Danson Otto Lang Jean Chretien Allan McKinnon Flora MacDonald JacquesMarc Lalonde Flynn John Crosbie Gilles Lamontagne Mark MacGuigan Jean Chretien Allan MacEachen JeanJacques Blais Allan MacEachen Mark MacGuigan Marc Lalonde Robert Coates Jean Chretien Donald Johnston 1980s Erik Nielsen John Crosbie 1980s Perrin Beatty Joe Clark Ray Hnatyshyn Michael Wilson Bill McKnight Doug Lewis BONUS : Name these plays by Oscar Wilde, for 10 points each. You have 30 seconds. (A) THE PAGE OF HERODIAS: Look at the moon! How strange the moon seems! She is like a woman rising from a tomb. She is like a dead woman. You would fancy she was looking for dead things. THE YOUNG SYRIAN: She has a strange look. -

Canada's Continuing Support of US Linkage Regulations For

Marquette Intellectual Property Law Review Volume 15 | Issue 1 Article 1 I'm Still Your Baby: Canada's Continuing Support of U.S. Linkage Regulations for Pharmaceuticals Ron A. Bouchard University of Manitoba, Canada Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/iplr Part of the Intellectual Property Commons Repository Citation Ron A. Bouchard, I'm Still Your Baby: Canada's Continuing Support of U.S. Linkage Regulations for Pharmaceuticals, 15 Intellectual Property L. Rev. 71 (2011). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/iplr/vol15/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Intellectual Property Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I’M STILL YOUR BABY: CANADA’S CONTINUING SUPPORT OF U.S. LINKAGE REGULATIONS FOR PHARMACEUTICALS RON A. BOUCHARD∗ ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................... 72 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 73 I. REVIEW OF EMPIRICAL STUDIES............................................................ 77 A. Study 1 ........................................................................................... 77 B. Study 2 ............................................................................................ 83 C. Study -

Accession No. 1986/428

-1- Liberal Party of Canada MG 28 IV 3 Finding Aid No. 655 ACCESSION NO. 1986/428 Box No. File Description Dates Research Bureau 1567 Liberal Caucus Research Bureau Briefing, Book - British Columbia, Vol. I July 1981 Liberal Caucus Research Bureau Briefing, Book - Saskatchewan, Vol. I and Sept. 1981 II Liberal Caucus Research Bureau Briefing, Book - Alberta, Vol. II May 20, 1981 1568 Liberal Caucus Research Bureau Briefing, Book - Manitoba, Vols. II and III 1981 Liberal caucus Research Bureau Briefing, Book - British Columbia, Vol. IV 1981 Elections & Executive Minutes 1569 Minutes of LPC National Executive Meetings Apr. 29, 1979 to Apr. 13, 1980 Poll by poll results of October 1978 By-Elections Candidates' Lists, General Elections May 22, 1979 and Feb. 18, 1980 Minutes of LPC National Executive Meetings June-Dec. 1981 1984 General Election: Positions on issues plus questions and answers (statements by John N. Turner, Leader). 1570 Women's Issues - 1979 General Election 1979 Nova Scotia Constituency Manual Mar. 1984 Analysis of Election Contribution - PEI & Quebec 1980 Liberal Government Anti-Inflation Controls and Post-Controls Anti-Inflation Program 2 LIBERAL PARTY OF CANADA MG 28, IV 3 Box No. File Description Dates Correspondence from Senator Al Graham, President of LPC to key Liberals 1978 - May 1979 LPC National Office Meetings Jan. 1976 to April 1977 1571 Liberal Party of Newfoundland and Labrador St. John's West (Nfld) Riding Profiles St. John's East (Nfld) Riding Profiles Burin St. George's (Nfld) Riding Profiles Humber Port-au-Port-St. -

Collection: Green, Max: Files Box: 42

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: Green, Max: Files Folder Title: Briefing International Council of the World Conference on Soviet Jewry 05/12/1988 Box: 42 To see more digitized collections visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digital-library To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/document-collection Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/citing National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ WITHDRAWAL SHEET Ronald Reagan Library Collection Name GREEN, MAX: FILES Withdrawer MID 11/23/2001 File Folder BRIEFING INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL & THE WORLD FOIA CONFERENCE ON SOVIET JEWRY 5/12/88 F03-0020/06 Box Number THOMAS 127 DOC Doc Type Document Description No of Doc Date Restrictions NO Pages 1 NOTES RE PARTICIPANTS 1 ND B6 2 FORM REQUEST FOR APPOINTMENTS 1 5/11/1988 B6 Freedom of Information Act - [5 U.S.C. 552(b)] B-1 National security classified Information [(b)(1) of the FOIA) B-2 Release would disclose Internal personnel rules and practices of an agency [(b)(2) of the FOIA) B-3 Release would violate a Federal statute [(b)(3) of the FOIA) B-4 Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential or financial Information [(b)(4) of the FOIA) B-8 Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted Invasion of personal privacy [(b)(6) of the FOIA) B-7 Release would disclose Information compiled for law enforcement purposes [(b)(7) of the FOIA) B-8 Release would disclose Information concerning the regulation of financial Institutions [(b)(B) of the FOIA) B-9 Release would disclose geological or geophysical Information concerning wells [(b)(9) of the FOIA) C.