The Requisites of Leadership in the Modern House of Commons 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsocialist-Issue54

VIRTUAL SEXUALITY BOLIVIAN ELECTIONS 54 NOV-JAN 2005/2006 ISSUE NO. 54 SPECIAL ISSUE ON CANADA & EMPIRE $4.95 HURRICANE KATRINA 7272006 86358 www.newsociallist.org EDITORIAL Canada and Empire Since the US government reacted to the attacks of No serious analysis of Canadian history or contemporary September 11th, 2001 by accelerating its push for global state polices towards Aboriginal communities can deny the dominance, there has been more talk about empire and impe- colonial nature of Canada or lend credence to a political strat- rialism than at any time since the 1970s. egy based on asserting the sovereignty of the same state that With Canadian troops and police in Afghanistan and denies Aboriginal Peoples and Quebec the right to self-deter- Haiti, the big boost in spending on the military in the last mination up to and including independence if they so federal budget and active government support for the “struc- choose. tural adjustment” policies of the International Monetary In our view, the notion that Canada is some kind of Fund and the World Bank that have inflicted so much harm dependent nation can’t be squared with the reality of the on people in the “Third World,” serious questions about Canadian state’s current role in Haiti or its pursuit of policies Canada’s relationship to imperialism are harder and harder to that destroy the livelihoods of millions of people in the ignore. Global South while giving free reign to multinational corpo- But because most anti-imperialist protest and analysis in rations – including Canadian companies - to plunder their Canada focuses on the US, such important questions often resources. -

John G. Diefenbaker: the Political Apprenticeship Of

JOHN G. DIEFENBAKER: THE POLITICAL APPRENTICESHIP OF A SASKATCHEWAN POLITICIAN, 1925-1940 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon by Methodius R. Diakow March, 1995 @Copyright Methodius R. Diakow, 1995. All rights reserved. In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department for the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or pUblication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of History University of Saskatchewan 9 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 ii ABSTRACT John G. Diefenbaker is most often described by historians and biographers as a successful and popular politician. -

Chretien Consensus

End of the CHRÉTIEN CONSENSUS? Jason Clemens Milagros Palacios Matthew Lau Niels Veldhuis Copyright ©2017 by the Fraser Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. The authors of this publication have worked independently and opinions expressed by them are, therefore, their own, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Fraser Institute or its supporters, Directors, or staff. This publication in no way implies that the Fraser Institute, its Directors, or staff are in favour of, or oppose the passage of, any bill; or that they support or oppose any particular political party or candidate. Date of issue: March 2017 Printed and bound in Canada Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data End of the Chrétien Consensus? / Jason Clemens, Matthew Lau, Milagros Palacios, and Niels Veldhuis Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-88975-437-9 Contents Introduction 1 Saskatchewan’s ‘Socialist’ NDP Begins the Journey to the Chrétien Consensus 3 Alberta Extends and Deepens the Chrétien Consensus 21 Prime Minister Chrétien Introduces the Chrétien Consensus to Ottawa 32 Myths of the Chrétien Consensus 45 Ontario and Alberta Move Away from the Chrétien Consensus 54 A New Liberal Government in Ottawa Rejects the Chrétien Consensus 66 Conclusions and Recommendations 77 Endnotes 79 www.fraserinstitute.org d Fraser Institute d i ii d Fraser Institute d www.fraserinstitute.org Executive Summary TheChrétien Consensus was an implicit agreement that transcended political party and geography regarding the soundness of balanced budgets, declining government debt, smaller and smarter government spending, and competi- tive taxes that emerged in the early 1990s and lasted through to roughly the mid-2000s. -

Understanding Stephen Harper

HARPER Edited by Teresa Healy www.policyalternatives.ca Photo: Hanson/THE Tom CANADIAN PRESS Understanding Stephen Harper The long view Steve Patten CANAdIANs Need to understand the political and ideological tem- perament of politicians like Stephen Harper — men and women who aspire to political leadership. While we can gain important insights by reviewing the Harper gov- ernment’s policies and record since the 2006 election, it is also essential that we step back and take a longer view, considering Stephen Harper’s two decades of political involvement prior to winning the country’s highest political office. What does Harper’s long record of engagement in conservative politics tell us about his political character? This chapter is organized around a series of questions about Stephen Harper’s political and ideological character. Is he really, as his support- ers claim, “the smartest guy in the room”? To what extent is he a con- servative ideologue versus being a political pragmatist? What type of conservatism does he embrace? What does the company he keeps tell us about his political character? I will argue that Stephen Harper is an economic conservative whose early political motivations were deeply ideological. While his keen sense of strategic pragmatism has allowed him to make peace with both conservative populism and the tradition- alism of social conservatism, he continues to marginalize red toryism within the Canadian conservative family. He surrounds himself with Governance 25 like-minded conservatives and retains a long-held desire to transform Canada in his conservative image. The smartest guy in the room, or the most strategic? When Stephen Harper first came to the attention of political observers, it was as one of the leading “thinkers” behind the fledgling Reform Party of Canada. -

"New World Order": Imperialist Barbarism

SPARTACIST Bush, Mulroney' Gloat Over Desert Massacre "New World Order": Imperialist Barbarism Rebours/AP Charred remains of imperialist slaughter of Iraqi soldiers withdrawing from Kuwait. As planes repeatedly bombed "killing box" for over 12 hours, pilots boasted It was "like shooting fish in a barrel." U.S. imperialism's easy win in its one-sided, bloody war of armbands. Bush gloats that Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein devastation against Iraq is a deadly danger to working people "walks amidst ruins," while a pumped-up officer in the field and the oppressed everywhere. trumpets Washington's messagc to "thc rest of the world": The flag-wavers came out in force, with military parades and "If the U.S. is going to deploy forces, watch out." yellow ribbons everywhere. The U.S. Congress staged a spec Washington's junior partners in Ottawa played their part tacle for the conquering commander in chief that rcsembled in raining death upon the people of Iraq. Now Joe Clark has something between a football pep rally and a Nazi beer haJJ been sent to tour the Near East, hoping to share the spotlight meeting. Democrats and Republicans alike repeatcdly rose to for helping with the slaughter, and sniffing around for a few ehant "Bush! Bush! Bush!" and wore American flags like (continued on page 12) 2 SPARTACIST/Canada Partisan Defense Committee Fund Appeal Defend Arrested British Spartacist! At a February 2 demonstration against the Gulf War in London Alastair Green, a comrade of the Spartacist League!Britain, was arrcsted, dragged off the march, hit in the face with a police helmet and then charged with "obstructing a police officer" and "threatening behaviour." The police action against our comrade was carried out expressly on the basis of the SL/B's political positions on the war-for the' defeat of U.S.!British imperialism and defense of Iraq. -

The Vitality of Quebec's English-Speaking Communities: from Myth to Reality

SENATE SÉNAT CANADA THE VITALITY OF QUEBEC’S ENGLISH-SPEAKING COMMUNITIES: FROM MYTH TO REALITY Report of the Standing Senate Committee on Official Languages The Honourable Maria Chaput, Chair The Honourable Andrée Champagne, P.C., Deputy Chair October 2011 (first published in March 2011) For more information please contact us by email: [email protected] by phone: (613) 990-0088 toll-free: 1 800 267-7362 by mail: Senate Committee on Official Languages The Senate of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1A 0A4 This report can be downloaded at: http://senate-senat.ca/ol-lo-e.asp Ce rapport est également disponible en français. Top photo on cover: courtesy of Morrin Centre CONTENTS Page MEMBERS ORDER OF REFERENCE PREFACE INTRODUCTION .................................................................................... 1 QUEBEC‘S ENGLISH-SPEAKING COMMUNITIES: A SOCIO-DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE ........................................................... 4 QUEBEC‘S ENGLISH-SPEAKING COMMUNITIES: CHALLENGES AND SUCCESS STORIES ...................................................... 11 A. Community life ............................................................................. 11 1. Vitality: identity, inclusion and sense of belonging ......................... 11 2. Relationship with the Francophone majority ................................. 12 3. Regional diversity ..................................................................... 14 4. Government support for community organizations and delivery of services to the communities ................................ -

The NDP's Approach to Constitutional Issues Has Not Been Electorally

Constitutional Confusion on the Left: The NDP’s Position in Canada’s Constitutional Debates Murray Cooke [email protected] First Draft: Please do not cite without permission. Comments welcome. Paper prepared for the Annual Meetings of the Canadian Political Science Association, June 2004, Winnipeg The federal New Democratic Party experienced a dramatic electoral decline in the 1990s from which it has not yet recovered. Along with difficulties managing provincial economies, the NDP was wounded by Canada’s constitutional debates. The NDP has historically struggled to present a distinctive social democratic approach to Canada’s constitution. Like its forerunner, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), the NDP has supported a liberal, (English-Canadian) nation-building approach that fits comfortably within the mainstream of Canadian political thought. At the same time, the party has prioritized economic and social polices rather than seriously addressing issues such as the deepening of democracy or the recognition of national or regional identities. Travelling without a roadmap, the constitutional debates of the 80s and 90s proved to be a veritable minefield for the NDP. Through three rounds of mega- constitutional debate (1980-82, 1987-1990, 1991-1992), the federal party leadership supported the constitutional priorities of the federal government of the day, only to be torn by disagreements from within. This paper will argue that the NDP’s division, lack of direction and confusion over constitution issues can be traced back to longstanding weaknesses in the party’s social democratic theory and strategy. First of all, the CCF- NDP embraced rather than challenged the parameters and institutions of liberal democracy. -

Alternative North Americas: What Canada and The

ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS What Canada and the United States Can Learn from Each Other David T. Jones ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20004 Copyright © 2014 by David T. Jones All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of author’s rights. Published online. ISBN: 978-1-938027-36-9 DEDICATION Once more for Teresa The be and end of it all A Journey of Ten Thousand Years Begins with a Single Day (Forever Tandem) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Borders—Open Borders and Closing Threats .......................................... 12 Chapter 2 Unsettled Boundaries—That Not Yet Settled Border ................................ 24 Chapter 3 Arctic Sovereignty—Arctic Antics ............................................................. 45 Chapter 4 Immigrants and Refugees .........................................................................54 Chapter 5 Crime and (Lack of) Punishment .............................................................. 78 Chapter 6 Human Rights and Wrongs .................................................................... 102 Chapter 7 Language and Discord .......................................................................... -

The 2006 Federal Liberal and Alberta Conservative Leadership Campaigns

Choice or Consensus?: The 2006 Federal Liberal and Alberta Conservative Leadership Campaigns Jared J. Wesley PhD Candidate Department of Political Science University of Calgary Paper for Presentation at: The Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan May 30, 2007 Comments welcome. Please do not cite without permission. CHOICE OR CONSENSUS?: THE 2006 FEDERAL LIBERAL AND ALBERTA CONSERVATIVE LEADERSHIP CAMPAIGNS INTRODUCTION Two of Canada’s most prominent political dynasties experienced power-shifts on the same weekend in December 2006. The Liberal Party of Canada and the Progressive Conservative Party of Alberta undertook leadership campaigns, which, while different in context, process and substance, produced remarkably similar outcomes. In both instances, so-called ‘dark-horse’ candidates emerged victorious, with Stéphane Dion and Ed Stelmach defeating frontrunners like Michael Ignatieff, Bob Rae, Jim Dinning, and Ted Morton. During the campaigns and since, Dion and Stelmach have been labeled as less charismatic than either their predecessors or their opponents, and both of the new leaders have drawn skepticism for their ability to win the next general election.1 This pair of surprising results raises interesting questions about the nature of leadership selection in Canada. Considering that each race was run in an entirely different context, and under an entirely different set of rules, which common factors may have contributed to the similar outcomes? The following study offers a partial answer. In analyzing the platforms of the major contenders in each campaign, the analysis suggests that candidates’ strategies played a significant role in determining the results. Whereas leading contenders opted to pursue direct confrontation over specific policy issues, Dion and Stelmach appeared to benefit by avoiding such conflict. -

Steven Estey Humble Human Rights Hero

THE FaCES oF Steven Estey HumblE HuMaN Rights Hero Spotlight: Green Entrepreneurs • Taking Healthy Snacks National Community Trail Blazing • Fresh Idea Makes Waves • The Swamp Man Mailed under Canada Post Publication Mail Sales No. 40031313 | Return Undeliverable Canadian Addresses to:Alumni Office, Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, NS B3H 3C3 FALL 2010 President’s Message 2010-2011 Alumni councIl EditoR: Fall 2010 Steve Proctor (BJ) President: Greg Poirier (MBA’03) Vice-President: Michael K. McKenzie (BComm’80) Art DirectioN and DesigN: Secretary: Mary-Evelyn Ternan (MEd’88, Spectacle Group BEd’70, BA’69) Lynn Redmond (BA’99) Past-President: Stephen Kelly (BSc’78) contributors This issue: David Carrigan (BComm’83) Brian Hayes 3 New Faces on the Alumni Council Sarah Chiasson ( MBA’06) Alan Johnson Blake Patterson 3 Alumni Outreach Program Cheryl Cook (BA’99) Suzanne Robicheau Marcel Dupupet (BComm’04) Richard Woodbury (BA Hon’04) 4 New Faces Sarah Ferguson (BComm’09) 6 Homburg Centre Breaks Ground Frank Gervais (DipEng’58) Advertising: Chandra Gosine (BA’81) (902) 420-5420 Cathy Hanrahan Cox (BA’06) Alumni DirecToR: Feature Articles Shelley Hessian (MBA’07, BComm’84) Patrick Crowley (BA’72) Omar Lodge (BComm’10) Myles McCormick (MEd’89, MA’87, BEd’77, BA’76) senioR Alumni offIcer : 8 The Faces of Steven Estey Margaret Melanson (BA’04) Kathy MacFarlane (Assoc’09) Humble Human Rights Hero could never list everything that makes me proud to be Craig Moore (BA’97) Assoc. VIcE President 11 Students Soar at the Atlantic Centre an Alumnus of Saint Mary’s University. On a weekly Ally Read (BA/BComm’07) External Affairs: basis, I hear about the difference that our family of Megan Roberts (BA’05) Margaret Murphy, (BA Hon, MA) 13 10 Cool Things I Karen Ross (BComm’77) students, professors, staff and alumni are making in a variety Wendy Sentner (BComm’01) Maroon & White is published for alumni of disciplines, media and countries. -

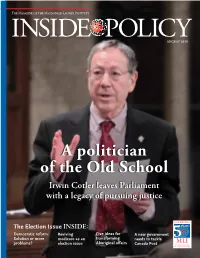

The August 2015 Issue of Inside Policy

AUGUST 2015 A politician of the Old School Irwin Cotler leaves Parliament with a legacy of pursuing justice The Election Issue INSIDE: Democratic reform: Reviving Five ideas for A new government Solution or more medicare as an transforming needs to tackle problems? election issue Aboriginal affairs Canada Post PublishedPublished by by the the Macdonald-Laurier Macdonald-Laurier Institute Institute PublishedBrianBrian Lee Lee Crowley, byCrowley, the Managing Macdonald-LaurierManaging Director,Director, [email protected] [email protected] Institute David Watson,JamesJames Anderson,Managing Anderson, Editor ManagingManaging and Editor, Editor,Communications Inside Inside Policy Policy Director Brian Lee Crowley, Managing Director, [email protected] James Anderson,ContributingContributing Managing writers:writers: Editor, Inside Policy Past contributors ThomasThomas S. AxworthyS. Axworthy ContributingAndrewAndrew Griffith writers: BenjaminBenjamin Perrin Perrin Thomas S. AxworthyDonald Barry Laura Dawson Stanley H. HarttCarin Holroyd Mike Priaro Peggy Nash DonaldThomas Barry S. Axworthy StanleyAndrew H. GriffithHartt BenjaminMike PriaroPerrin Mary-Jane Bennett Elaine Depow Dean Karalekas Linda Nazareth KenDonald Coates Barry PaulStanley Kennedy H. Hartt ColinMike Robertson Priaro Carolyn BennettKen Coates Jeremy Depow Paul KennedyPaul Kennedy Colin RobertsonGeoff Norquay Massimo Bergamini Peter DeVries Tasha Kheiriddin Benjamin Perrin Brian KenLee Crowley Coates AudreyPaul LaporteKennedy RogerColin Robinson Robertson Ken BoessenkoolBrian Lee Crowley Brian -

1866 (C) Circa 1510 (A) 1863

BONUS : Paintings together with their year of completion. (A) 1863 (B) 1866 (C) circa 1510 Vancouver Estival Trivia Open, 2012, FARSIDE team BONUS : Federal cabinet ministers, 1940 to 1990 (A) (B) (C) (D) Norman Rogers James Ralston Ernest Lapointe Joseph-Enoil Michaud James Ralston Mackenzie King James Ilsley Louis St. Laurent 1940s Andrew McNaughton 1940s Douglas Abbott Louis St. Laurent James Ilsley Louis St. Laurent Brooke Claxton Douglas Abbott Lester Pearson Stuart Garson 1950s 1950s Ralph Campney Walter Harris John Diefenbaker George Pearkes Sidney Smith Davie Fulton Donald Fleming Douglas Harkness Howard Green Donald Fleming George Nowlan Gordon Churchill Lionel Chevrier Guy Favreau Walter Gordon 1960s Paul Hellyer 1960s Paul Martin Lucien Cardin Mitchell Sharp Pierre Trudeau Leo Cadieux John Turner Edgar Benson Donald Macdonald Mitchell Sharp Edgar Benson Otto Lang John Turner James Richardson 1970s Allan MacEachen 1970s Ron Basford Donald Macdonald Don Jamieson Barney Danson Otto Lang Jean Chretien Allan McKinnon Flora MacDonald JacquesMarc Lalonde Flynn John Crosbie Gilles Lamontagne Mark MacGuigan Jean Chretien Allan MacEachen JeanJacques Blais Allan MacEachen Mark MacGuigan Marc Lalonde Robert Coates Jean Chretien Donald Johnston 1980s Erik Nielsen John Crosbie 1980s Perrin Beatty Joe Clark Ray Hnatyshyn Michael Wilson Bill McKnight Doug Lewis BONUS : Name these plays by Oscar Wilde, for 10 points each. You have 30 seconds. (A) THE PAGE OF HERODIAS: Look at the moon! How strange the moon seems! She is like a woman rising from a tomb. She is like a dead woman. You would fancy she was looking for dead things. THE YOUNG SYRIAN: She has a strange look.