Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 36 Harold Pinter: the Dramatist and His World

Chapter 36 Harold Pinter: The Dramatist and His World Background Nobel winner, Harold Pinter (1930- 2008) was born in London, England in a Jewish family. Some of the most recognizable features in his plays are the use of understatement, small talk, reticence , and silence. These devices are employed to convey the substance of a character’s thoughts. At the outbreak of World War II, Pinter was evacuated from the city to Cornwall; to be wrenched from his parents was a traumatic event for Pinter. He lived with 26 other boys in a castle on the coast. At the age of 14, he returned to London. "The condition of being bombed has never left me," Pinter later said. At school one of Pinter's main intellectual interests was English literature, particularly poetry. He also read works of Franz Kafka and Ernest Hemingway, and started writing poetry for little magazines in his teens. The seeds of rebellion in Pinter could be spotted early on when he refused to do the National Service. As a young man, he studied acting at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and the Central School of Speech and Drama, but soon left to undertake an acting career under the stage name David Baron. He travelled around Ireland in a Shakespearean company and spent years working in provincial repertory before deciding to turn his attention to playwriting. Pinter was married from 1956 to the actress Vivien Merchant. For a time, they lived in Notting Hill Gate in a slum. Eventually Pinter managed to borrow some money and move away. -

Kaviya Coaching Center Online Study Materials Pg-Trb English- Unit-Test-1-Part-2 –Cell No :9600736379

www.TnpscExamOnlineResult.blogspot.in www.Kanchikalvi.com KAVIYA COACHING CENTER ONLINE STUDY MATERIALS PG-TRB ENGLISH- UNIT-TEST-1-PART-2 –CELL NO :9600736379 PG-TRB ENGLISH UNIT-TEST-1-PART-2 WITH ANSWERS Choose the best alternative for each question: 1. Who wrote Where Angels Fear to Tread, A Passage to India, Howard's End and Aspects of the Novel? a. George Orwell c. Edward Morgan Forster b. H.G. Wells d. Virginia Woolf 2. Identify the writer of these works: Eyeless in Gaza, Point Counter Point, Brave New World and Island. a. Graham Greene c. D.H. Lawrence b. Aldous Huxley d. E.M. Forster 3. Name the author of these novels: The Power and the Glory, The Man Within, England Made Me and The [lean of the Matter. a. Graham Greene c. Aldous Huxley b. E.M. Forster d. Hillaire Belloc www.Kanchikalvi.com4. Whose works are The Quiet American, A Burnt-Out Case, A GUI] for Sale and The Comedians? a. Joyce Cary c. Graham Greene b. George Orwell d. Aldous Huxley 5. Who wrote The Horse's Mouth, Herself Sulptised, The Aliican Witch and An American Visitor? a. Aldous Huxley c. Joyce Cary b. Graham Greene d. Hillaire Belloc 6. Identify the novelist who wrote Liza of Lambeth, Of Human Bondage, Cakes and Ale, and The Razor's Edge a. Hillaire Belloc c. E.M. Forster b. Aldous Huxley d. Somerset Maugham 7. Name the writer who wrote 30 novels including Fortitude, The Green Mirror; The Dark Forest and The Cathedral. a. Somerset Maugham c. -

Stanley S. Atherton ALAN SILLITOE's BATTLEGROUND

Stanley S. Atherton ALAN SILLITOE'S BATTLEGROUND I FoR ALAN S1LLIT0E's HEROES, to live at all is to fight, and this belligerence de- fines their existence in the English working-class world that they inhabit. Their struggles, while reflecting the difficulties of individual protagonists, are primarily class confliots echoing the author's disillusion with contemporary English society. The early Seaton-family novels, Saturday Niglit and Sunday Morning and Key to the Door, along with the shorter works The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner and The Decline and Fall of Frankie Buller, offer a series of loud and angry protests which define Sillitoe's working-class perspective, while the later novels, The Death of William Posters and A Tree on Fire, move beyond this co a more positive approach to the problems of existence raised in the earlier work. The battles of his heroes, whether they are visceral or cerebral, internal or external, idealistic or pragmatic, are all fought to achieve Sillitoe's utopian dream of a better world. The central campaigns in Sillitoe's war are aimed at toppling a social structure built on inequality and characterized by haves and have-nots. The early fiction makes it clear: the two groups are enemies. Smith, the Borstal boy in The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner, talks of "them" and "us" and reveals tha:t "they don't see eye to eye with us and we don't see eye to eye with them."1 His thoughts on the lonely practice-runs over the early-morning countryside lead him to conclude that "by sending me to Borstal they've shown me the knife, and from now on I know something I didn't know before: that it's war between me and them. -

From Free Cinema to British New Wave: a Story of Angry Young Men

SUPLEMENTO Ideas, I, 1 (2020) 51 From Free Cinema to British New Wave: A Story of Angry Young Men Diego Brodersen* Introduction In February 1956, a group of young film-makers premiered a programme of three documentary films at the National Film Theatre (now the BFI Southbank). Lorenza Mazzetti, Lindsay Anderson, Karel Reisz and Tony Richardson thought at the time that “no film can be too personal”, and vehemently said so in their brief but potent manifesto about Free Cinema. Their documentaries were not only personal, but aimed to show the real working class people in Britain, blending the realistic with the poetic. Three of them would establish themselves as some of the most inventive and irreverent British filmmakers of the 60s, creating iconoclastic works –both in subject matter and in form– such as Saturday Day and Sunday Morning, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner and If… Those were the first significant steps of a New British Cinema. They were the Big Screen’s angry young men. What is British cinema? In my opinion, it means many different things. National cinemas are much more than only one idea. I would like to begin this presentation with this question because there have been different genres and types of films in British cinema since the beginning. So, for example, there was a kind of cinema that was very successful, not only in Britain but also in America: the films of the British Empire, the films about the Empire abroad, set in faraway places like India or Egypt. Such films celebrated the glory of the British Empire when the British Empire was almost ending. -

The Twentieth Century

XV The Twentieth Century JUDIE NEWMAN, JOHN SAUNDERS, JOHN CHALKER, and RENE WEIS This chapter has the following sections: 1. The Novel, by Judie Newman and John Saunders; 2. Verse, by John Chalker; 3. Prose Drama, by Ren6 Weis. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ywes/article/64/1/415/1672491 by guest on 30 September 2021 1. The Novel This section has three categories: (a) General Studies, by Judie Newman; (b) Individual Authors: 1900-45, by John Saunders; (c) Individual Authors: Post-1945, by Judie Newman. The attribution [J-S.] denotes isolated reviews by John Saunders. (a) General Studies The relevant volumes of BHI and BNB provide useful bibliographical aid. MFS contains helpful lists of books received and of books reviewed. Current Contents is most useful in listing the contents of periodicals as they appear. Alistair Davies's An Annotated Critical Bibliography of Modernism1 promises to be similarly useful, with sections on Yeats, Wyndham Lewis, Lawrence, and Eliot arranged chronologically under various headings and the first part of the book devoted to the theory and practice of modernism. Over 200 entries take us from Axel's Castle to 1980, with rational subdivisions so that if one wants to investigate 'the Marxist Critique of Modernism', for example, one finds eight books and essays listed. Critical comments are brief but sensible, and there are indexes of authors and subjects. Davies makes his preferences clear, while including fair coverage of other points of view. [J.S.] Volume 21 of the Gale Information Guide Series completes their bibliography of English Fiction 1900-19501 with entries from Joyce to Woolf. -

JG Ballard's Reappraisal of Space

Keyes: J.G. Ballard’s Reappraisal of Space 48 From a ‘metallized Elysium’ to the ‘wave of the future’: J.G. Ballard’s Reappraisal of Space Jarrad Keyes Independent Scholar _____________________________________ Abstract: This essay argues that the ‘concrete and steel’ trilogy marks a pivotal moment in Ballard’s intellectual development. From an earlier interest in cities, typically London, Crash ([1973] 1995b), Concrete Island (1974] 1995a) and High-Rise ([1975] 2005) represent a threshold in Ballard’s spatial representations, outlining a critique of London while pointing the way to a suburban reorientation characteristic of his later works. While this process becomes fully realised in later representations of Shepperton in The Unlimited Dream Company ([1979] 1981) and the concept of the ‘virtual city’ (Ballard 2001a), the trilogy makes a number of important preliminary observations. Crash illustrates the roles automobility and containerisation play in spatial change. Meanwhile, the topography of Concrete Island delineates a sense of economic and spatial transformation, illustrating the obsolescence of the age of mechanical reproduction and the urban form of the metropolis. Thereafter, the development project in High-Rise is linked to deindustrialisation and gentrification, while its neurological metaphors are key markers of spatial transformation. The essay concludes by considering how Concrete Island represents a pivotal text, as its location demonstrates. Built in the 1960s, the Westway links the suburban location of Crash to the West with the Central London setting of High-Rise. In other words, Concrete Island moves athwart the new economy associated with Central London and the suburban setting of Shepperton, the ‘wave of the future’ as envisaged in Ballard’s works. -

Book Sale Feb 10P.Pub

DAVID HANCOCK & CO AUCTIONEERS SALE BY AUCTION Special Sale of Books Saturday 10th February 2007 at 12:00pm AUCTION OFFICE Sheraton House High Street Moreton in Marsh Jubilee Hall Gloucestershire (to the rear of St. George’s Hall), GL56 0AG Blockley Tel: (01608) 650428 Nr. Moreton-in-Marsh, Gloucestershire Fax: (01608) 650540 GL56 9BY Viewing Friday 9th February 4-8pm & Mobile (Not during sale): 0789 992 7112 morning of the sale from 9am Catalogues £2.00 www.davidhancock-co.co.uk IMPORTANT 1. All lots will be sold subject to the Conditions of Sale as exhibited in the sale room. 2. All lots will be at the purchasers risk at the fall of the hammer. 3. CHEQUES WILL NOT BE ACCEPTED FROM PERSONS UNKNOWN TO THE We hold regular sales of Antique, AUCTIONEER UNLESS PRIOR BANKING ARRANGEMENTS HAVE BEEN MADE. Intending purchasers wishing to pay by cheque must ask their bank to forward to us Reproduction and Modern Furniture, details of their credit worthiness stating the likely sum involved. Silver, Plate, Jewellery, China, Porcelain, Glass, Pictures, We do not accept debit or credit cards. Books, Miscellanea, Collectables and Outside Effects 4. NO LOTS TO BE REMOVED UNTIL PAID FOR. 5. All lots to be removed on the day of sale before 6pm unless prior AT arrangements have been made with the auctioneers. St George’s and Jubilee Halls, Blockley, Nr Moreton in 6. All lots purchased on commission must be collected and paid for by 6pm on sale day (unless prior arrangements have been made). Marsh, Gloucestershire. We also undertake valuations of chattels for Sale, Insurance, Probate and Family Division. -

{PDF EPUB} ~Download the Midwich Cuckoos by John Wyndham John Wyndham: the Unread Bestseller

{Read} {PDF EPUB} ~download The Midwich Cuckoos by John Wyndham John Wyndham: The unread bestseller. One of the drawbacks of being a bestselling author is that no one reads you properly. Sure they read you, but do they really read you? I've been thinking about this because Nicola Swords and I have just made a documentary for Radio 4 about John Wyndham. Wyndham is probably the most successful British science fiction writer after HG Wells, and his books have never been out of print. He continues to haunt the public imagination – either through adaptations of his own work (last Christmas gave us a new Day of the Triffids on the BBC) or through thinly disguised homages (witness the opening of Danny Boyle's 28 Days Later, which almost exactly resembles the first chapters of The Day of the Triffids, and is in its turn parodied in the opening of Shaun of the Dead). But because his books are so familiar, maybe we don't look too closely at them. I read a lot of Wyndham when I was a teenager. Then, a few years ago, when I was looking around for books to adapt as a Radio 4 "classic serial", I thought of The Midwich Cuckoos. Rereading it, I was startled to find a searching novel of moral ambiguities where once I'd seen only an inventive but simple SF thriller. If you don't know the story, the village of Midwich is visited by aliens who put the whole place to sleep for 24 hours and depart; some weeks later all the women of childbearing age find they are pregnant, and give birth to golden-eyed telepathic children whose powers are soon turned against the village and the world. -

Violence and Dystopia

Violence and Dystopia Violence and Dystopia: Mimesis and Sacrifice in Contemporary Western Dystopian Narratives By Daniel Cojocaru Violence and Dystopia: Mimesis and Sacrifice in Contemporary Western Dystopian Narratives By Daniel Cojocaru This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Daniel Cojocaru All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7613-5 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7613-1 For my daughter, and in loving memory of my father (1949 – 1991) TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................... ix Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Introduction 1.1 Modern Dystopia ............................................................................. 1 1.2 René Girard’s Mimetic Theory ...................................................... 10 1.2.1 Imitative Desire ..................................................................... 10 1.2.2 Violence and the Sacred ........................................................ 16 1.2.3 Girard and the Bible ............................................................. -

Malcolm Bradbury and the Creation of Creative Writing at UEA ABSTRACT When Did Creative Writing Cour

Lise Jaillant Myth Maker: Malcolm Bradbury and the Creation of Creative Writing at UEA1 ABSTRACT When did creative writing courses really appear in the UK? The usual story is that the first creative writing programme was launched in 1970 at the University of East Anglia, under the leadership of Malcolm Bradbury. Ian McEwan is often presented as the first student in creative writing, a role he has always rejected – insisting that he studied for an MA in literature with the option to submit creative work for the final dissertation. As Kathryn Holeywell has shown, creative writing was already offered for assessment at UEA in the 1960s. This article tells a more complete history of creative writing in Britain, a history that takes into account the experimentations of the 1960s and the rise of literary prizes in the 1980s – without ignoring Bradbury’s important role. KEYWORDS: Creative writing in literature courses; literary prizes; celebrity; writing communities The story is familiar and goes something like this: in 1970, the young Ian McEwan saw an announcement for a new postgraduate course in creative writing at the University of East Anglia. He gave a call to Professor Malcolm Bradbury, sent a writing sample, and became the first (and only) student of the first MA in creative writing in the UK. McEwan, of course, went on to become one of the most successful British writers of literary fiction. And Bradbury was knighted in 2000, shortly before his death, for his services to literature. This is a good story, which emphasises the extraordinary luck of both McEwan and Bradbury. -

APPENDIX ALCOTT, Louisa May

APPENDIX ALCOTT, Louisa May. American. Born in Germantown, Pennsylvania, 29 November 1832; daughter of the philosopher Amos Bronson Alcott. Educated at home, with instruction from Thoreau, Emerson, and Theodore Parker. Teacher; army nurse during the Civil War; seamstress; domestic servant. Edited the children's magazine Merry's Museum in the 1860's. Died 6 March 1888. PUBLICATIONS FOR CHILDREN Fiction Flower Fables. Boston, Briggs, 1855. The Rose Family: A Fairy Tale. Boston, Redpath, 1864. Morning-Glories and Other Stories, illustrated by Elizabeth Greene. New York, Carleton, 1867. Three Proverb Stories. Boston. Loring, 1868. Kitty's Class Day. Boston, Loring, 1868. Aunt Kipp. Boston, Loring, 1868. Psyche's Art. Boston, Loring, 1868. Little Women; or, Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy, illustrated by Mary Alcott. Boston. Roberts. 2 vols., 1868-69; as Little Women and Good Wives, London, Sampson Low, 2 vols .. 1871. An Old-Fashioned Girl. Boston, Roberts, and London, Sampson Low, 1870. Will's Wonder Book. Boston, Fuller, 1870. Little Men: Life at Pluff?field with Jo 's Boys. Boston, Roberts, and London. Sampson Low, 1871. Aunt Jo's Scrap-Bag: My Boys, Shawl-Straps, Cupid and Chow-Chow, My Girls, Jimmy's Cruise in the Pinafore, An Old-Fashioned Thanksgiving. Boston. Roberts. and London, Sampson Low, 6 vols., 1872-82. Eight Cousins; or, The Aunt-Hill. Boston, Roberts, and London, Sampson Low. 1875. Rose in Bloom: A Sequel to "Eight Cousins." Boston, Roberts, 1876. Under the Lilacs. London, Sampson Low, 1877; Boston, Roberts, 1878. Meadow Blossoms. New York, Crowell, 1879. Water Cresses. New York, Crowell, 1879. Jack and Jill: A Village Story. -

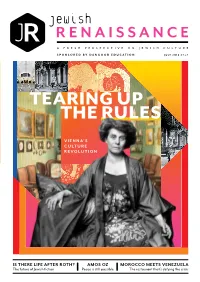

Tearing up the Rules

Jewish RENAISSANCE A FRESH PERSPECTIVE ON JEWISH CULTURE SPONSORED BY DANGOOR EDUCATION JULY 2018 £7.25 TEARING UP THE RULES VIENNA’S CULTURE REVOLUTION IS THERE LIFE AFTER ROTH? AMOS OZ MOROCCO MEETS VENEZUELA The future of Jewish fiction Peace is still possible The restaurant that’s defying the crisis JR Pass on your love of Jewish culture for future generations Make a legacy to Jewish Renaissance ADD A LEGACY TO JR TO YOUR WILL WITH THIS SIMPLE FORM WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK/CODICIL GO TO: WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK/DONATIONS FOR INFORMATION ON ALL WAYS TO SUPPORT JR CHARITY NUMBER 1152871 JULY 2018 CONTENTS WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK JR YOUR SAY… Reader’s rants, raves 4 and views on the April issue of JR. WHAT’S NEW We announce the 6 winner of JR’s new arts award; Mike Witcombe asks: is there life after Roth? FEATURE Amos Oz on Israel at 10 70, the future of peace, and Trump’s controversial embassy move. FEATURE An art installation in 12 French Alsace is breathing new life into an old synagogue. NATALIA BRAND NATALIA © PASSPORT Vienna: The writers, 14 artists, musicians and thinkers who shaped modernism. Plus: we speak to the contemporary arts activists working in Vienna today. MUSIC Composer Na’ama Zisser tells Danielle Goldstein about her 30 CONTENTS opera, Mamzer Bastard. ART A new show explores the 1938 32 exhibition that brought the art the Nazis had banned to London. FILM Masha Shpolberg meets 14 34 the director of a 1968 film, which followed a group of Polish exiles as they found haven on a boat in Copenhagen.