Malcolm Bradbury and the Creation of Creative Writing at UEA ABSTRACT When Did Creative Writing Cour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Routledge History of Literature in English

The Routledge History of Literature in English ‘Wide-ranging, very accessible . highly attentive to cultural and social change and, above all, to the changing history of the language. An expansive, generous and varied textbook of British literary history . addressed equally to the British and the foreign reader.’ MALCOLM BRADBURY, novelist and critic ‘The writing is lucid and eminently accessible while still allowing for a substantial degree of sophistication. The book wears its learning lightly, conveying a wealth of information without visible effort.’ HANS BERTENS, University of Utrecht This new guide to the main developments in the history of British and Irish literature uniquely charts some of the principal features of literary language development and highlights key language topics. Clearly structured and highly readable, it spans over a thousand years of literary history from AD 600 to the present day. It emphasises the growth of literary writing, its traditions, conventions and changing characteristics, and also includes literature from the margins, both geographical and cultural. Key features of the book are: • An up-to-date guide to the major periods of literature in English in Britain and Ireland • Extensive coverage of post-1945 literature • Language notes spanning AD 600 to the present • Extensive quotations from poetry, prose and drama • A timeline of important historical, political and cultural events • A foreword by novelist and critic Malcolm Bradbury RONALD CARTER is Professor of Modern English Language in the Department of English Studies at the University of Nottingham. He is editor of the Routledge Interface series in language and literary studies. JOHN MCRAE is Special Professor of Language in Literature Studies at the University of Nottingham and has been Visiting Professor and Lecturer in more than twenty countries. -

View 2019 Edition Online

Emmanuel Emmanuel College College MAGAZINE 2018–2019 Front Court, engraved by R B Harraden, 1824 VOL CI MAGAZINE 2018–2019 VOLUME CI Emmanuel College St Andrew’s Street Cambridge CB2 3AP Telephone +44 (0)1223 334200 The Master, Dame Fiona Reynolds, in the new portrait by Alastair Adams May Ball poster 1980 THE YEAR IN REVIEW I Emmanuel College MAGAZINE 2018–2019 VOLUME CI II EMMANUEL COLLEGE MAGAZINE 2018–2019 The Magazine is published annually, each issue recording college activities during the preceding academical year. It is circulated to all members of the college, past and present. Copy for the next issue should be sent to the Editors before 30 June 2020. News about members of Emmanuel or changes of address should be emailed to [email protected], or via the ‘Keeping in Touch’ form: https://www.emma.cam.ac.uk/members/keepintouch. College enquiries should be sent to [email protected] or addressed to the Development Office, Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP. General correspondence concerning the Magazine should be addressed to the General Editor, College Magazine, Dr Lawrence Klein, Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP. Correspondence relating to obituaries should be addressed to the Obituaries Editor (The Dean, The Revd Jeremy Caddick), Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP. The college telephone number is 01223 334200, and the email address is [email protected]. If possible, photographs to accompany obituaries and other contributions should be high-resolution scans or original photos in jpeg format. The Editors would like to express their thanks to the many people who have contributed to this issue, with a special nod to the unstinting assistance of the College Archivist. -

Redgrove Papers: Letters

Redgrove Papers: letters Archive Date Sent To Sent By Item Description Ref. No. Noel Peter Answer to Kantaris' letter (page 365) offering back-up from scientific references for where his information came 1 . 01 27/07/1983 Kantaris Redgrove from - this letter is pasted into Notebook one, Ref No 1, on page 365. Peter Letter offering some book references in connection with dream, mesmerism, and the Unconscious - this letter is 1 . 01 07/09/1983 John Beer Redgrove pasted into Notebook one, Ref No 1, on page 380. Letter thanking him for a review in the Times (entitled 'Rhetoric, Vision, and Toes' - Nye reviews Robert Lowell's Robert Peter 'Life Studies', Peter Redgrove's 'The Man Named East', and Gavin Ewart's 'The Young Pobbles Guide To His Toes', 1 . 01 11/05/1985 Nye Redgrove Times, 25th April 1985, p. 11); discusses weather-sensitivity, and mentions John Layard. This letter is pasted into Notebook one, Ref No 1, on page 373. Extract of a letter to Latham, discussing background work on 'The Black Goddess', making reference to masers, John Peter 1 . 01 16/05/1985 pheromones, and field measurements in a disco - this letter is pasted into Notebook one, Ref No 1, on page 229 Latham Redgrove (see 73 . 01 record). John Peter Same as letter on page 229 but with six and a half extra lines showing - this letter is pasted into Notebook one, Ref 1 . 01 16/05/1985 Latham Redgrove No 1, on page 263 (this is actually the complete letter without Redgrove's signature - see 73 . -

Illusion and Reality in the Fiction of Iris Murdoch: a Study of the Black Prince, the Sea, the Sea and the Good Apprentice

ILLUSION AND REALITY IN THE FICTION OF IRIS MURDOCH: A STUDY OF THE BLACK PRINCE, THE SEA, THE SEA AND THE GOOD APPRENTICE by REBECCA MODEN A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY (Mode B) Department of English School of English, Drama and American and Canadian Studies University of Birmingham September 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis considers how Iris Murdoch radically reconceptualises the possibilities of realism through her interrogation of the relationship between life and art. Her awareness of the unreality of realist conventions leads her to seek new forms of expression, resulting in daring experimentation with form and language, exploration of the relationship between author and character, and foregrounding of the artificiality of the text. She exposes the limitations of language, thereby involving herself with issues associated with the postmodern aesthetic. The Black Prince is an artistic manifesto in which Murdoch repeatedly destroys the illusion of the reality of the text in her attempts to make language communicate truth. Whereas The Black Prince sees Murdoch contemplating Hamlet, The Sea, The Sea meditates on The Tempest, as Murdoch returns to Shakespeare in order to examine the relationship between life and art. -

`The Campus Novel`: Kingsley Amis, Malcolm Bradbury, David Lodge – a Comparative Study

`The Campus Novel`: Kingsley Amis, Malcolm Bradbury, David Lodge – a comparative study Lucie Mohelníková Bachelor Thesis 2009 ***scanned submission page 2*** ABSTRAKT Hlavním zám ěrem této práce nebylo pouze p řiblížit žánr “univerzitního románu” a jeho nejznám ější britské autory, ale také vysv ětlit a ukázat, pro č se univerzitní romány Kingsleyho Amise a jeho následovník ů Malcolma Bradburyho a Davida Lodge t ěší tak velké popularit ě. Každý z t ěchto autor ů m ěl sv ůj osobitý styl psaní a vytvo řil nezapomenutelný satirický román. Klí čová slova: rozlobení mladí muži, Hnutí, Jim Dixon, Stuart Treece, Phillip Swallow, Morris Zapp, univerzitní román ABSTRACT The main intention of this thesis is not only to introduce the genre of “campus novel” and its most known British authors but also to explain and demonstrate why the campus novels by Kingsley Amis and his successors Malcolm Bradbury and David Lodge are that much popular. Each of these authors had his own individual style of writing and created an unforgettable satiric novel. Keywords: Angry Young Men, The Movement, Jim Dixon, Stuart Treece, Phillip Swallow, Morris Zapp, campus novel ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisor Mgr. Barbora Kašpárková for her kind help and guidance throughout my thesis. DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own and certify that any secondary material used has been acknowledged in the text and listed in the bibliography. March 13, 2009 …………………………………… CONTENT 1 CAMPUS NOVEL ........................................................................................................9 -

Poetic Madness in Malcolm Bradbury's Eating People Is Wrong

Poetic Madness 5 ___ 10.2478/abcsj-2021-0002 Poetic Madness in Malcolm Bradbury’s Eating People Is Wrong NOUREDDINE FRIJI King Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia Abstract This article addresses the age-old correlation between poetic genius and madness as represented in Malcolm Bradbury’s academic novel Eating People Is Wrong (1959), zeroing in on a student-cum-poet and a novelist- cum-poet called Louis Bates and Carey Willoughby, respectively. While probing this unexplored theme in Bradbury’s novel, I pursue three primary aims. To begin with, I seek to demonstrate that certain academics’ tendency to fuse or confuse the poetic genius of their students and colleagues with madness is not only rooted in inherited assumptions, generalizations, and exaggerations but also in their own antipathy towards poets on the grounds that they persistently diverge from social norms. Second, I endeavour to ignite readers’ enthusiasm about the academic novel subgenre by underscoring the vital role it plays in energizing scholarly debate about the appealing theme of poetic madness. Lastly, the study concedes that notwithstanding the prevalence of prejudice among their populations, universities, on the whole, do not relinquish their natural veneration for originality, discordant views, and rewarding dialogue. Keywords: academic novel, genius, poetic madness, Malcolm Bradbury, originality, critical thinking Much Madness is divinest Sense – To a discerning Eye – Much Sense – the starkest Madness – ’Tis the Majority In this, as All, prevail – Assent – and you -

Doktori Disszertáció

Eötvös Loránd Tudományegyetem Bölcsészettudományi Kar DOKTORI DISSZERTÁCIÓ Székely Péter The Academic Novel in the Age of Postmodernity: The Anglo-American Metafictional Academic Novel Irodalomtudományi Doktori Iskola, A doktori Iskola vezetője: Dr. Kulcsár Szabó Ernő Modern Angol és Amerikai Irodalom Program, A program vezetője: Dr. Sarbu Aladár A bizottság tagjai és tudományos fokozatuk: Elnök: Dr. Kállay Géza PhD., dr. habil., egyetemi tanár Hivatalosan felkért bírálók: Dr. Fülöp Zsuzsanna CSc., egyetemi docens Dr. Sarbu Aladár DSc., egyetemi tanár Titkár: Dr. Farkas Ákos PhD., egyetemi docens További tagok: Dr. Bényei Tamás PhD. CSc., dr. habil., egyetemi docens Dr. Péteri Éva PhD., egyetemi adjunktus Dr. Takács Ferenc PhD., egyetemi docens Témavezető és tudományos fokozata: Dr. Dávidházi Péter DSc., dr. habil., egyetemi tanár Budapest, 2009 Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 4 I. WHAT IS AN ACADEMIC NOVEL? .......................................................................................... 11 1.1. NOMENCLATURE ................................................................................................................................. 11 1.2. THE DIFFICULTIES OF DEFINING ACADEMIC FICTION ................................................................................ 12 1.2.1. THE STEREOTYPICAL NOTION OF THE ACADEMIC NOVEL ............................................................................ 12 1.2.2. -

Academics and the Psychological Contract: the Formation and Manifestation of the Psychological Contract Within the Academic Role

University of Huddersfield Repository Johnston, Alan Academics and the Psychological Contract: The formation and manifestation of the Psychological Contract within the academic role. Original Citation Johnston, Alan (2021) Academics and the Psychological Contract: The formation and manifestation of the Psychological Contract within the academic role. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/35485/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Academics and the Psychological Contract: The formation and manifestation of the Psychological Contract within the academic role. ALAN JOHNSTON A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Business Administration 8th February 2021 1 Declaration I, Alan Johnston, declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. -

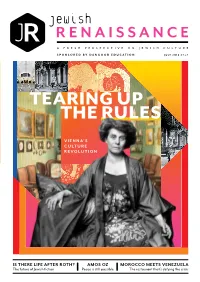

Tearing up the Rules

Jewish RENAISSANCE A FRESH PERSPECTIVE ON JEWISH CULTURE SPONSORED BY DANGOOR EDUCATION JULY 2018 £7.25 TEARING UP THE RULES VIENNA’S CULTURE REVOLUTION IS THERE LIFE AFTER ROTH? AMOS OZ MOROCCO MEETS VENEZUELA The future of Jewish fiction Peace is still possible The restaurant that’s defying the crisis JR Pass on your love of Jewish culture for future generations Make a legacy to Jewish Renaissance ADD A LEGACY TO JR TO YOUR WILL WITH THIS SIMPLE FORM WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK/CODICIL GO TO: WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK/DONATIONS FOR INFORMATION ON ALL WAYS TO SUPPORT JR CHARITY NUMBER 1152871 JULY 2018 CONTENTS WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK JR YOUR SAY… Reader’s rants, raves 4 and views on the April issue of JR. WHAT’S NEW We announce the 6 winner of JR’s new arts award; Mike Witcombe asks: is there life after Roth? FEATURE Amos Oz on Israel at 10 70, the future of peace, and Trump’s controversial embassy move. FEATURE An art installation in 12 French Alsace is breathing new life into an old synagogue. NATALIA BRAND NATALIA © PASSPORT Vienna: The writers, 14 artists, musicians and thinkers who shaped modernism. Plus: we speak to the contemporary arts activists working in Vienna today. MUSIC Composer Na’ama Zisser tells Danielle Goldstein about her 30 CONTENTS opera, Mamzer Bastard. ART A new show explores the 1938 32 exhibition that brought the art the Nazis had banned to London. FILM Masha Shpolberg meets 14 34 the director of a 1968 film, which followed a group of Polish exiles as they found haven on a boat in Copenhagen. -

A CRITICAL PATH Securing the Future of Higher Education in England

A CRITICAL PATH Securing the Future of Higher Education in England IPPR Commission on the Future of Higher Education 2013 1 IPPR RESEARCH STAFF Nick Pearce is director of IPPR. Rick Muir is associate director for public service reform at IPPR. Jonathan Clifton is a senior research fellow at IPPR. Annika Olsen is a researcher at IPPR. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Commissioners would like to thank Nick Pearce, Rick Muir, Jonathan Clifton and Annika Olsen for their help with researching and writing this report, and London Economics for modelling the higher education funding system. They would also like to thank those organisations and individuals who submitted evidence or agreed to be interviewed as part of this project. In particular, they would like to thank the staff and students who facilitated their learning visits to higher education institutions in Sheffield and Newcastle. They would also like to thank Jon Wilson, along with all those who organised and participated in the joint seminar series with King’s College London, and Marc Stears for his guidance in the early stages of the project. ABOUT IPPR IPPR, the Institute for Public Policy Research, is the UK’s leading progressive thinktank. We are an independent charitable organisation with more than 40 staff members, paid interns and visiting fellows. Our main office is in London, with IPPR North, IPPR’s dedicated thinktank for the North of England, operating out of offices in Newcastle and Manchester. The purpose of our work is to assist all those who want to create a society where every citizen lives a decent and fulfilled life, in reciprocal relationships with the people they care about. -

Ad Alta: the Birmingham Journal of Literature Volume X, 2018 ‘Unheard’

Ad Alta: The Birmingham Journal of Literature Volume X, 2018 ‘Unheard’ AD ALTA: THE BIRMINGHAM JOURNAL OF LITERATURE VOLUME X ‘UNHEARD’ 2018 Cover Image: (Untitled) excerpt from ‘Manifestations of Caledonian Road’ 2018 (digital and mixed media) by David Baldock Printed by Central Print, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK This issue is available online: birmingham.ac.uk/adalta Ad Alta: The Birmingham Journal of Literature (Print) ISSN 2517-6951 Ad Alta: The Birmingham Journal of Literature (Online) ISSN 2517-696X ⓒ Ad Alta: The Birmingham Journal of Literature Questions and Submissions: Rebekah Andrew ([email protected]) GENERAL EDITOR POETRY AND ARTS Rebekah Andrew Nellie Cole Alice Seville REVIEW PANEL Marie Allègre BOOK REVIEWS EDITOR Hannah Comer Katherine Randall Polly Duxfield Marine Furet Liam Harrison NOTES EDITORS Aurora Faye Martinez Kim Gauthier James McCrick Michelle Michel Antonia Wimbush PROOFS EDITOR EDITORIAL BOARD Yasmine Baker Joshua Allsop Emily Buffey Jessica Pirie Tom White Ad Alta: The Birmingham Journal of Literature wishes to acknowledge the hard work and generosity of a number of individuals, without whom this journal would never have made its way into your hands, or onto your computer screen. Firstly, our editorial board, who have provided wonderful advice and support throughout the entire process of producing this journal. We also wish to thank Will Cooper of Central Print, who provided assistance throughout the printing process. Also, our contributors, who have dedicated so much time and energy to write and redraft submissions, and the review panel, who provided excellent comments and feedback on our submissions. Thanks are also due to Rowanne Conway and Eve Green. -

Defining CLIL

Something to talk about Integrating content and language in tertiary education Dr Elisabeth Wielander 18 March, 2017 Outline What is CLIL? Conceptual and methodological frameworks Findings and lessons from Europe and UK Examples from the classroom Defining CLIL CLIL: umbrella term for context-bound varieties like • immersion (Språkbad, Sweden) • bilingual education (Hungary) • multilingual education (Latvia) • integrated curriculum (Spain) • Languages across the curriculum (Fremdsprache als Arbeitssprache, Austria) • language-enriched instruction (Finland) Eurydice (2006: 64-67) There is no single blueprint that can be applied in the same way in different countries.” Coyle (2007: 5) Lessons from immersion clearly defined role of focus on form: •metalinguistic awareness •opportunities for production practice sociolinguistic and sociocultural context different • L and C integrated flexibly along a continuum aim: functional rather than (near) native-like competence Pérez-Caňado (2012) Language Triptych Language of learning CLIL linguistic progression Language learning and language using Language for Language learning through learning adapted from Coyle / Hood / Marsh (2010: 36) Language in CLIL language used for academic and specific purposes puts different demands on linguistic processing and production - needs instruction and training Cummins (2008): • BICS (Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills) = “conversational fluency in a language” • CALP (Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency) = “access to and command of the oral and written