A Fine White Flying Myth of One's Own: Sylvia Plath in Fiction – a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anne Sexton, Her Therapy Tapes, and the Meaning of Privacy

UCLA UCLA Women's Law Journal Title To Bedlam and Part Way Back: Anne Sexton, Her Therapy Tapes, and the Meaning of Privacy Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2sn2c9hk Journal UCLA Women's Law Journal, 2(0) Author Lehrich, Tamar R. Publication Date 1992 DOI 10.5070/L321017562 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California TO BEDLAM AND PART WAY BACK: ANNE SEXTON, HER THERAPY TAPES, AND THE MEANING OF PRIVACY Tamar R. Lehrich* INTRODUCTION I have ridden in your cart, driver, waved my nude arms at villages going by, learning the last bright routes, survivor where your flames still bite my thigh and my ribs crack where your wheels wind. A woman like that is not ashamed to die. I have been her kind.' The poet Anne Sexton committed suicide in October, 1974, at the age of forty-five. Three months earlier, she had celebrated the 21st birthday of her elder daughter, Linda Gray Sexton, and on that occasion appointed her as Sexton's literary executor. 2 Anne Sexton * J.D. candidate, Harvard Law School, 1992; B.A., Yale University, 1987. This Essay was written in Alan A. Stone's seminar, "Psychoanalysis and Legal Assump- tions," given at Harvard Law School in the fall of 1991. The seminar provided a rare opportunity to explore theories of law, medical ethics, and artistic expression from an interdisciplinary perspective. In addition to Professor Stone, I am grateful to Martha Minow and Mithra Merryman for their insightful comments and challenging questions and to Carmel Sella and Lisa Hone for their invaluable editorial talents. -

1 MAPS – IQP CMJ – 1303 Augmenting the Modern American Poetry Site's Update with Confessional Poetry, Plath and Snodgrass

1 MAPS – IQP CMJ – 1303 Augmenting the Modern American Poetry Site’s Update With Confessional Poetry, Plath and Snodgrass An Interactive Qualifying Project to be submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science By: _______________________ _______________________ Sneha Shastry and Deanna Souza Date: 06 May 2014 Sponsored by the Modern American Poetry Website Approved: ________________________________ Professor James Cocola, Major Advisor 2 Abstract This report describes the techniques we used to assist the transition of the Modern American Poetry Site (MAPS) from an obsolescent version to a modern iteration. MAPS’s editors updated the site with a more robust content management system. We assisted this transition by creating MAPS pages for a school of poetry and a new poet; adding old and new content to an existing poet's page; assembling a historical timeline; and laying the foundations of a contributor's guide. We conclude the report with a display of our results and recommendations for further work with MAPS. 3 Table of Contents Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................... 2 Table of Contents ................................................................................................................ 3 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ 8 The Reasons -

Double Image : the Hughes-Plath Relationship As Told in Birthday Letters

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Double Image: The Hughes-Plath Relationship As Told in Birthday Letters. .A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in English at Massey University Helen Jacqueline Cain 2002 II CONTENTS Abstract................................................ .iii Acknowledgements ....................................... .iv Introduction.............................................. 1 Chapter One -Ted Hughes on Trial. ......................... 10 Chapter Two - The Structure of Birthday Letters. ...............22 Chapter Three - Delivered of Yourself........................ .40 Chapter Four - The Man in Black. .................... 53 Chapter Five - Daddy Coming Up From Out of the Well......... 69 Chapter Six - Fixed Stars Govern a Life ........................74 Conclusion............................................... 80 Works Cited.............................................. 83 Works Consulted......................................... 87 iii ABSTRACT Proceeding from a close reading of both Birthdqy Letters and the poems of Sylvia Plath, and also from a consideration of secondary and biographical works, I argue that implicit within Birthdqy Letters is an explanation for Sylvia Plath's death and Ted Hughes's role in it. Birthdqy Letters is a collection of 88 poems written by Ted Hughes to his first wife, the poet Sylvia Plath, in the years following her death. There are two aspects to the explanation Ted Hughes provides. Both are connected to Sylvia Plath's poetry. Her development as a poet not only causes her death as told in Birthdqy Letters, but it also renders Ted Hughes incapable of helping her, because through her poetry he is made to adopt the role of Plath's father. -

The+Ted+Hughes+Society+Journal+

Ted Hughes Society Journal Volume VIII Issue 2 The Ted Hughes Society Journal Editors Dr James Robinson Durham University Reviews Editor Prof. Terry Gifford Bath Spa University Editorial Assistant Dr Mike Sweeting Editorial Board Prof. Terry Gifford Bath Spa University Dr Yvonne Reddick University of Central Lancashire Prof. Neil Roberts University of Sheffield Dr Carrie Smith Cardiff University Dr Mike Sweeting Dr Mark Wormald Pembroke College Cambridge Production Manager Dr David Troupes Published by the Ted Hughes Society. All matters pertaining to the Ted Hughes Society Journal should be sent to: [email protected] You can contact the Ted Hughes Society via email at: [email protected] Questions about joining the Society should be sent to: [email protected] thetedhughessociety.org This Journal is copyright of the Ted Hughes Society but copyright of the articles is the property of their authors. Written consent should be requested from the copyright holder before reproducing content for personal and/or educational use; requests for permission should be addressed to the Editor. Commercial copying is prohibited without written consent. 2 Contents Editorial ......................................................................................................................4 List of abbreviations of works by Ted Hughes .......................................................... 7 ‘Owned by everyone’: a Cambridge Conference on the Salmon ............................... 8 Mark Wormald A Prologue to -

Spring 1986 Editor: the Cover Is the Work of Lydia Sparrow

'sReview Spring 1986 Editor: The cover is the work of Lydia Sparrow. J. Walter Sterling Managing Editor: Maria Coughlin Poetry Editor: Richard Freis Editorial Board: Eva Brann S. Richard Freis, Alumni representative Joe Sachs Cary Stickney Curtis A. Wilson Unsolicited articles, stories, and poems are welcome, but should be accom panied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope in each instance. Reasoned comments are also welcome. The St. John's Review (formerly The Col lege) is published by the Office of the Dean. St. John's College, Annapolis, Maryland 21404. William Dyal, Presi dent, Thomas Slakey, Dean. Published thrice yearly, in the winter, spring, and summer. For those not on the distribu tion list, subscriptions: $12.00 yearly, $24.00 for two years, or $36.00 for three years, paya,ble in advance. Address all correspondence to The St. John's Review, St. John's College, Annapolis, Maryland 21404. Volume XXXVII, Number 2 and 3 Spring 1986 ©1987 St. John's College; All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited. ISSN 0277-4720 Composition: Best Impressions, Inc. Printing: The John D. Lucas Printing Company Contents PART I WRITINGS PUBLISHED IN MEMORY OF WILLIAM O'GRADY 1 The Return of Odysseus Mary Hannah Jones 11 God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob Joe Sachs 21 On Beginning to Read Dante Cary Stickney 29 Chasing the Goat From the Sky Michael Littleton 37 The Miraculous Moonlight: Flannery O'Connor's The Artificial Nigger Robert S. Bart 49 The Shattering of the Natural Order E. A. Goerner 57 Through Phantasia to Philosophy Eva Brann 65 A Toast to the Republic Curtis Wilson 67 The Human Condition Geoffrey Harris PART II 71 The Homeric Simile and the Beginning of Philosophy Kurt Riezler 81 The Origin of Philosophy Jon Lenkowski 93 A Hero and a Statesman Douglas Allanbrook Part I Writings Published in Memory of William O'Grady THE ST. -

Blind Faith Chase and Status

Blind Faith Chase And Status 1 / 4 Blind Faith Chase And Status 2 / 4 3 / 4 Watch the video for Blind Faith from Chase & Status's No More Idols for free, and see the artwork, lyrics and similar artists.. "Blind Faith" is a song by British drum and bass duo Chase & Status. It was released as the second official single, and the third overall, from their second studio .... New music video: Chase & Status - Blind Faith. The south London dance duo come over all nostalgic for the rave days in their latest video.. Lyrics to 'Blind Faith' by Chase & Status . Sweet sensation I am a man with a heavy heart and I dare not turn the pages Fighting with automatic self destruction, .... Discover releases, reviews, credits, songs, and more about Chase and Status* Ft. Liam Bailey - Blind Faith at Discogs. Complete your Chase and Status* Ft.. "Blind Faith" by Chase & Status feat. Liam Bailey sampled The Sunburst Band's "Ease Your Mind". Listen to both songs on WhoSampled, the ultimate database .... One of the videos I directed and edited recently for Chase & Status' live tour in collaboration with The Light .... Check out Blind Faith [feat. Liam Bailey] by Chase & Status on Amazon Music. Stream ad-free or purchase CD's and MP3s now on Amazon.com.. Capo 3rd Fret...although feel free to move it to suit your voice Have a listen to this one on youtube feat. devlin an some fat chick,BIG TUNEE.. try this one out,may .... Blind Faith Lyrics: Sweet sensation (sensation) / I am a man with a heavy heart / And I dare not turn the pages / Fighting with automatic self destruction / I- It's a ... -

Novelty and Canonicity in Lucian's Verae Historiae

Parody and Paradox: Novelty and Canonicity in Lucian’s Verae Historiae Katharine Krauss Barnard College Comparative Literature Class of 2016 Abstract: The Verae historiae is famous for its paradoxical claim both condemning Lucian’s literary predecessors for lying and also confessing to tell no truths itself. This paper attempts to tease out this contradictory parallel between Lucian’s own text and the texts of those he parodies even further, using a text’s ability to transmit truth as the grounds of comparison. Focusing on the Isle of the Blest and the whale episodes as moments of meta-literary importance, this paper finds that Lucian’s text parodies the poetic tradition for its limited ability to transmit truth, to express its distance from that tradition, and yet nevertheless to highlight its own limitations in its communication of truth. In so doing, Lucian reflects upon the relationship between novelty and adherence to tradition present in the rhetoric of the Second Sophistic. In the prologue of his Verae historiae, Lucian writes that his work, “τινα…θεωρίαν οὐκ ἄµουσον ἐπιδείξεται” (1.2).1 Lucian flags his work as one that will undertake the same project as the popular rhetorical epideixis since the Verae historiae also “ἐπιδείξεται.” Since, as Tim Whitmarsh writes, “sophistry often privileges new ideas” (205:36-7), Lucian’s contemporary audience would thus expect his text to entertain them at least in part through its novelty. Indeed, the Verae historiae fulfills these expectations by offering a new presentation of the Greek literary canon. In what follows I will first explore how Lucian’s parody of an epic katabasis in the Isle of the Blest episode criticizes the ability of the poetic tradition to transmit truth. -

Kalasiris and Charikleia: Mentorship and Intertext in Heliodorus' Aithiopika

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2017 Kalasiris and Charikleia: Mentorship and Intertext in Heliodorus' Aithiopika Lauren Jordan Wood College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Wood, Lauren Jordan, "Kalasiris and Charikleia: Mentorship and Intertext in Heliodorus' Aithiopika" (2017). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1004. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1004 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kalasiris and Charikleia: Mentorship and Intertext in Heliodorus’ Aithiopika A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Classical Studies from The College of William and Mary by Lauren Wood Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ William Hutton, Director ________________________________________ Vassiliki Panoussi ________________________________________ Suzanne Hagedorn Williamsburg, VA April 17, 2017 Wood 2 Kalasiris and Charikleia: Mentorship and Intertext in Heliodorus’ Aithiopika Odyssean and more broadly Homeric intertext figures largely in Greco-Roman literature of the first to third centuries AD, often referred to in scholarship as the period of the Second Sophistic.1 Second Sophistic authors work cleverly and often playfully with Homeric characters, themes, and quotes, echoing the traditional stories in innovative and often unexpected ways. First to fourth century Greek novelists often play with the idea of their protagonists as wanderers and exiles, drawing comparisons with the Odyssey and its hero Odysseus. -

Narrative Techniques in Twenty-First Century Popular

NARRATIVE TECHNIQUES IN TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY POPULAR HOLOCAUST FICTION By Andrea Gapsch April 2021 ________________________ A Thesis presented to The Honors Tutorial College at Ohio University ________________________ In partial fulfillMent of the requireMents for graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with the degree of Bachelor of Arts in English. ________________________ Gapsch 2 Table of Contents Introduction Chapter One CaMp Sisters: Representations of FeMale Friendship and Networks of Support in Rose Under Fire and The Lilac Girls Chapter Two FaMilies and Dual TiMelines: Exploring Representations of Third Generation Holocaust Survivors in The Storyteller and Sarah’s Key Chapter Three The Nonfiction Novel: Comparing The Tattooist of Auschwitz and The Librarian of Auschwitz Conclusion Gapsch 3 Introduction As I began collecting sources for this project in early 2020, Auschwitz celebrated the 75th anniversary of its liberation. Despite more than 75 years of separation from the Holocaust, AMerican readers are still fascinated with the subject. In her book A Thousand Darknesses: Lies and Truth in Holocaust Fiction, Ruth Franklin mentions the fear of “Holocaust fatigue” that was discussed in 1980s and 1990s AMerican media, by which she meant the worry that AMericans had heard too about the Holocaust and could not take any more (222). This, Franklin feared, would lead to insensitivity from the general public, even in the face of a massive tragedy such as the Holocaust. After all, in his 1994 book Holocaust Representation: Art within the Limits of History and Ethics, Berel Lang estiMates Holocaust writing to include “tens of thousands” texts, spanning fiction, draMa, MeMoir, poetry, history monographs, and more (35). -

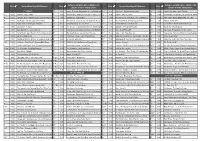

Price Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price Follow Us on Twitter

Follow us on twitter @PiccadillyRecs for Follow us on twitter @PiccadillyRecs for Price ✓ Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price ✓ Price ✓ Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price ✓ updates on items selling out etc. updates on items selling out etc. 7" SINGLES 7" 14.99 Queen : Bohemian Rhapsody/I'm In Love With My Car 12" 22.99 John Grant : Remixes Are Also Magic 12" 9.99 Lonnie Liston Smith : Space Princess 7" 12.99 Anderson .Paak : Bubblin' 7" 13.99 Sharon Ridley : Where Did You Learn To Make Love The 12" Way You 11.99Do Hipnotic : Are You Lonely? 12" 10.99 Soul Mekanik : Go Upstairs/Echo Beach (feat. Isabelle Antena) 7" 16.99 Azymuth : Demos 1973-75: Castelo (Version 1)/Juntos Mais 7" Uma Vez9.99 Saint Etienne : Saturday Boy 12" 9.99 Honeyblood : The Third Degree/She's A Nightmare 12" 11.99 Spirit : Spirit - Original Mix/Zaf & Phil Asher Edit 7" 10.99 Bad Religion : My Sanity/Chaos From Within 7" 12.99 Shit Girlfriend : Dress Like Cher/Socks On The Beach 12" 13.99 Hot 8 Brass Band : Working Together E.P. 12" 9.99 Stalawa : In East Africa 7" 9.99 Erykah Badu & Jame Poyser : Tempted 7" 10.99 Smiles/Astronauts, etc : Just A Star 12" 9.99 Freddie Hubbard : Little Sunflower 12" 10.99 Joe Strummer : The Rockfield Studio Tracks 7" 6.99 Julien Baker : Red Door 7" 15.99 The Specials : 10 Commandments/You're Wondering Now 12" 15.99 iDKHOW : 1981 Extended Play EP 12" 19.99 Suicide : Dream Baby Dream 7" 6.99 Bang Bang Romeo : Cemetry/Creep 7" 10.99 Vivian Stanshall & Gargantuan Chums (John Entwistle & Keith12" Moon)14.99 : SuspicionIdles : Meat EP/Meta EP 10" 13.99 Supergrass : Pumping On Your Stereo/Mary 7" 12.99 Darrell Banks : Open The Door To Your Heart (Vocal & Instrumental) 7" 8.99 The Straight Arrows : Another Day In The City 10" 15.99 Japan : Life In Tokyo/Quiet Life 12" 17.99 Swervedriver : Reflections/Think I'm Gonna Feel Better 7" 8.99 Big Stick : Drag Racing 7" 10.99 Tindersticks : Willow (Feat. -

SWR2 Feature Am Sonntag Ich Habe Sie Geheiratet, Weil Sie Mich Gefragt Hat Eine Dichterehe: Sylvia Plath Und Ted Hughes Von Manuela Reichart

SWR2 MANUSKRIPT ESSAYS FEATURES KOMMENTARE VORTRÄGE SWR2 Feature am Sonntag Ich habe sie geheiratet, weil sie mich gefragt hat Eine Dichterehe: Sylvia Plath und Ted Hughes Von Manuela Reichart Sendung: Dienstag, 20. Dezember 2016, 14.05 Uhr Redaktion: Walter Filz Produktion: WDR 2015 Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. Service: SWR2 Feature am Sonntag können Sie auch als Live-Stream hören im SWR2 Webradio unter www.swr2.de oder als Podcast nachhören:http://www1.swr.de/podcast/xml/swr2/feature.xml Mitschnitte aller Sendungen der Redaktion SWR2 Feature am Sonntag sind auf CD erhältlich beim SWR Mitschnittdienst in Baden-Baden zum Preis von 12,50 Euro. Bestellungen über Telefon: 07221/929-26030 Bestellungen per E-Mail: [email protected] Kennen Sie schon das Serviceangebot des Kulturradios SWR2? Mit der kostenlosen SWR2 Kulturkarte können Sie zu ermäßigten Eintrittspreisen Veranstaltungen des SWR2 und seiner vielen Kulturpartner im Sendegebiet besuchen. Mit dem Infoheft SWR2 Kulturservice sind Sie stets über SWR2 und die zahlreichen Veranstaltungen im SWR2-Kulturpartner-Netz informiert. Jetzt anmelden unter 07221/300 200 oder swr2.de Sprecherin 1 (Tagebücher S. 184) Samstag morgen, 10. März 1956. Bitte mach das er kommt, und gib mir die Beweglichkeit & den Mumm, ihm Respekt vor mir einzuflößen, sein Interesse zu wecken, damit ich mich nicht mit lautem oder hysterischem Geschrei auf ihn stürze; ruhig, sanft, locker, Baby, locker. Wahrscheinlich streift er im Moment mit sieben skandinavischen Liebhaberinnen durch die Krokusse in den backs. Und ich sitze wie eine Spinne herum, warte, hier zu Hause; Penelope webt Netze aus Webster und verbrennt Spindeln aus Tourneur. -

The Ted Hughes Society Journal

The Ted Hughes Society Journal Volume VIII Issue 1 The Ted Hughes Society Journal Co-Editors Dr James Robinson Durham University Dr Mark Wormald Pembroke College Cambridge Reviews Editor Prof. Terry Gifford Bath Spa University Editorial Assistant Dr Mike Sweeting Editorial Board Prof. Terry Gifford Bath Spa University Dr Yvonne Reddick University of Central Lancashire Prof. Neil Roberts University of Sheffield Dr Carrie Smith Cardiff University Production Manager Dr David Troupes Published by the Ted Hughes Society. All matters pertaining to the Ted Hughes Society Journal should be sent to: [email protected] You can contact the Ted Hughes Society via email at: [email protected] Questions about joining the Society should be sent to: [email protected] thetedhughessociety.org This Journal is copyright of the Ted Hughes Society but copyright of the articles is the property of their authors. Written consent should be requested from the copyright holder before reproducing content for personal and/or educational use; requests for permission should be addressed to the Editor. Commercial copying is prohibited without written consent. 2 Contents Editorial ......................................................................................................................4 Mark Wormald List of abbreviations of works by Ted Hughes .......................................................... 7 The Wound that Bled Lupercal: Ted Hughes in Massachusetts .............................. 8 David Troupes ‘Right to