Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

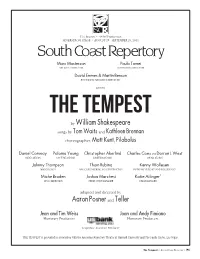

By William Shakespeare Aaron Posner and Teller

51st Season • 483rd Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / AUGUST 29 - SEPTEMBER 28, 2014 Marc Masterson Paula Tomei ARTISTIC DIRECTOR MANAGING DIRECTOR David Emmes & Martin Benson FOUNDING ARTISTIC DIRECTORS presents THE TEMPEST by William Shakespeare songs by Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennan choreographer, Matt Kent, Pilobolus Daniel Conway Paloma Young Christopher Akerlind Charles Coes AND Darron L West SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN Johnny Thompson Thom Rubino Kenny Wollesen MAGIC DESIGN MAGIC ENGINEERING AND CONSTRUCTION INSTRUMENT DESIGN AND WOLLESONICS Miche Braden Joshua Marchesi Katie Ailinger* MUSIC DIRECTION PRODUCTION MANAGER STAGE MANAGER adapted and directed by Aaron Posner and Teller Jean and Tim Weiss Joan and Andy Fimiano Honorary Producers Honorary Producers Corporate Associate Producer THE TEMPEST is presented in association with the American Repertory Theater at Harvard University and The Smith Center, Las Vegas. The Tempest • SOUTH COAST REPERTORY • P1 CAST OF CHARACTERS Prospero, a magician, a father and the true Duke of Milan ............................ Tom Nelis* Miranda, his daughter .......................................................................... Charlotte Graham* Ariel, his spirit servant .................................................................................... Nate Dendy* Caliban, his adopted slave .............................. Zachary Eisenstat*, Manelich Minniefee* Antonio, Prospero’s brother, the usurping Duke of Milan ......................... Louis Butelli* Gonzala, -

Sundance Institute Announces Casts for Summer Theatre Laboratory

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE For more information contact: June 21, 2006 Irene Cho [email protected], 801.328.3456 SUNDANCE INSTITUTE ANNOUNCES CASTS FOR SUMMER THEATRE LABORATORY AWARD-WINNING ACTORS ANTHONY RAPP, RAÚL ESPARZA AND OTHERS TO WORKSHOP SEVEN NEW PLAYS AT JULY LAB IN UTAH Salt Lake City, UT – Today, Sundance Institute announced the acting ensemble for the 2006 Sundance Institute Theatre Laboratory, to be held July 10-30, 2006 at the Sundance Resort in Utah. The company includes: Bradford Anderson, Nancy Anderson, Whitney Bashor, Judy Blazer, Reg E. Cathey, Will Chase, Johanna Day, Raúl Esparza, Jordan Gelber, Kimberly Hebert Gregory, Carla Harting, Roderick Hill, Nicholas Hormann, Christina Kirk, Ezra Knight, Judy Kuhn, Anika Larsen, Piter Marek, Kelly McCreary, Chris Messina, Jennifer Mudge, Novella Nelson, Toi Perkins, Anthony Rapp, Gareth Saxe, Tregoney Shepherd, Michael Stuhlbarg and Price Waldman. The seven plays to be developed at the 2006 Sundance Institute Theatre Laboratory include: CITIZEN JOSH, by Josh Kornbluth, directed by David Dower, an improvisational solo show which strives to rescue “democracy” from the sloganeers in a personal autobiographical format; CURRENT NOBODY, by Melissa James Gibson, directed by Daniel Aukin, a modern reinterpretation of Homer’s The Odyssey; GEOMETRY OF FIRE, by Stephen Belber, directed by Lucie Tiberghien, which weaves the story of an American reservist just back from Iraq and a Saudi-American citizen investigating his father’s death; THE EVILDOERS, by David Adjmi, directed by Rebecca Taichman, a play in which the marriage of two couples unravel in a dark yet comedic context; …AND JESUS MOONWALKS THE MISSISSIPPI, by Marcus Gardley, directed by Matt August, a poetic retelling of the Demeter myth set during the Civil War; KIND HEARTS AND CORONETS, book by Robert L. -

From the Odyssey, Part 1: the Adventures of Odysseus

from The Odyssey, Part 1: The Adventures of Odysseus Homer, translated by Robert Fitzgerald ANCHOR TEXT | EPIC POEM Archivart/Alamy Stock Photo Archivart/Alamy This version of the selection alternates original text The poet, Homer, begins his epic by asking a Muse1 to help him tell the story of with summarized passages. Odysseus. Odysseus, Homer says, is famous for fighting in the Trojan War and for Dotted lines appear next to surviving a difficult journey home from Troy.2 Odysseus saw many places and met many the summarized passages. people in his travels. He tried to return his shipmates safely to their families, but they 3 made the mistake of killing the cattle of Helios, for which they paid with their lives. NOTES Homer once again asks the Muse to help him tell the tale. The next section of the poem takes place 10 years after the Trojan War. Odysseus arrives in an island kingdom called Phaeacia, which is ruled by Alcinous. Alcinous asks Odysseus to tell him the story of his travels. I am Laertes’4 son, Odysseus. Men hold me formidable for guile5 in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky’s rim. My home is on the peaked sea-mark of Ithaca6 under Mount Neion’s wind-blown robe of leaves, in sight of other islands—Dulichium, Same, wooded Zacynthus—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy’s training; I shall not see on earth a place more dear, though I have been detained long by Calypso,7 loveliest among goddesses, who held me in her smooth caves to be her heart’s delight, as Circe of Aeaea,8 the enchantress, desired me, and detained me in her hall. -

Jacques-Louis David

Jacques-Louis David THE FAREWELL OF TELEMACHUS AND EUCHARIS Jacques-Louis David THE FAREWELL OF TELEMACHUS AND EUCHARIS Dorothy Johnson GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART Los ANGELES For my parents, Alice and John Winter, and for Johnny Christopher Hudson, Publisher Cover: Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748 — 1825). The Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis, 1818 Benedicte Gilman, Editor (detail). Oil on canvas, 87.2 x 103 cm (34% x 40/2 in.). Elizabeth Burke Kahn, Production Coordinator Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum (87.PA.27). Jeffrey Cohen, Designer Lou Meluso, Photographer Frontispiece: (Getty objects, 87.PA.27, 86.PA.740) Jacques-Louis David. Self-Portrait, 1794. Oil on canvas, 81 x 64 cm (31/8 x 25/4 in.). Paris, © 1997 The J. Paul Getty Museum Musee du Louvre (3705). © Photo R.M.N. 17985 Pacific Coast Highway Malibu, California 90265-5799 All works of art are reproduced (and photographs Mailing address: provided) courtesy of the owners, unless otherwise P.O. Box 2112 indicated. Santa Monica, California 90407-2112 Typography by G&S Typesetters, Inc., Library of Congress Austin, Texas Cataloging-in-Publication Data Printed by C & C Offset Printing Co., Ltd., Hong Kong Johnson, Dorothy. Jacques-Louis David, the Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis / Dorothy Johnson, p. cm.—(Getty Museum studies on art) Includes bibliographical references (p. — ). ISBN 0-89236-236-7 i. David, Jacques Louis, 1748 — 1825. Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis. 2. David, Jacques Louis, 1748-1825 Criticism and interpretation. 3. Telemachus (Greek mythology)—Art. 4. Eucharis (Greek mythology)—Art. I. Title. -

Spring 1986 Editor: the Cover Is the Work of Lydia Sparrow

'sReview Spring 1986 Editor: The cover is the work of Lydia Sparrow. J. Walter Sterling Managing Editor: Maria Coughlin Poetry Editor: Richard Freis Editorial Board: Eva Brann S. Richard Freis, Alumni representative Joe Sachs Cary Stickney Curtis A. Wilson Unsolicited articles, stories, and poems are welcome, but should be accom panied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope in each instance. Reasoned comments are also welcome. The St. John's Review (formerly The Col lege) is published by the Office of the Dean. St. John's College, Annapolis, Maryland 21404. William Dyal, Presi dent, Thomas Slakey, Dean. Published thrice yearly, in the winter, spring, and summer. For those not on the distribu tion list, subscriptions: $12.00 yearly, $24.00 for two years, or $36.00 for three years, paya,ble in advance. Address all correspondence to The St. John's Review, St. John's College, Annapolis, Maryland 21404. Volume XXXVII, Number 2 and 3 Spring 1986 ©1987 St. John's College; All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited. ISSN 0277-4720 Composition: Best Impressions, Inc. Printing: The John D. Lucas Printing Company Contents PART I WRITINGS PUBLISHED IN MEMORY OF WILLIAM O'GRADY 1 The Return of Odysseus Mary Hannah Jones 11 God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob Joe Sachs 21 On Beginning to Read Dante Cary Stickney 29 Chasing the Goat From the Sky Michael Littleton 37 The Miraculous Moonlight: Flannery O'Connor's The Artificial Nigger Robert S. Bart 49 The Shattering of the Natural Order E. A. Goerner 57 Through Phantasia to Philosophy Eva Brann 65 A Toast to the Republic Curtis Wilson 67 The Human Condition Geoffrey Harris PART II 71 The Homeric Simile and the Beginning of Philosophy Kurt Riezler 81 The Origin of Philosophy Jon Lenkowski 93 A Hero and a Statesman Douglas Allanbrook Part I Writings Published in Memory of William O'Grady THE ST. -

Calasiris the Pseudo-Greek Hero: Odyssean Allusions in Heliodorus' Aethiopica

Calasiris the Pseudo-Greek Hero: Odyssean Allusions in Heliodorus' Aethiopica Christina Marie Bartley A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master’s degree in Classical Studies Department of Classics and Religious Studies Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Christina Marie Bartley, Ottawa, Canada, 2021 Table of Contents Abbreviations ..................................................................................................................... iii Abstract .............................................................................................................................. vi Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................... vii Introduction ..................................................................................................................... viii 1. The Structural Markers of the Aethiopica .......................................................................1 1.1.Homeric Strategies of Narration ..........................................................................................2 1.1.1. In Medias Res .................................................................................................................3 1.2. Narrative Voices .................................................................................................................8 1.2.1. The Anonymous Primary Narrator ................................................................................9 1.2.2. Calasiris........................................................................................................................10 -

JACQUES ROUSSEAU's EMILE By

TOWARD AN UNDERSTANDING OF THE NOVELISTIC DIMENSION OF JEAN- JACQUES ROUSSEAU’S EMILE by Stephanie Miranda Murphy A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science University of Toronto © Copyright by Stephanie Miranda Murphy 2020 Toward an Understanding of the Novelistic Dimension of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Emile Stephanie Miranda Murphy Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science ABSTRACT The multi-genre combination of philosophic and literary expression in Rousseau’s Emile provides an opportunity to explore the relationship between the novelistic structure of this work and the substance of its philosophical teachings. This dissertation explores this matter through a textual analysis of the role of the novelistic dimension of the Emile. Despite the vast literature on Rousseau’s manner of writing, critical aspects of the novelistic form of the Emile remain either misunderstood or overlooked. This study challenges the prevailing image in the existing scholarship by arguing that Rousseau’s Emile is a prime example of how form and content can fortify each other. The novelistic structure of the Emile is inseparable from Rousseau’s conception and communication of his philosophy. That is, the novelistic form of the Emile is not simply harmonious with the substance of its philosophical content, but its form and content also merge to reinforce Rousseau’s capacity to express his teachings. This dissertation thus proposes to demonstrate how and why the novelistic -

Year of Ulysses

YEAR OF ULYSSES M VP By Stefan Krecsy and the Modernist Versions Project Team 2014 CC-BY TABLE OF CONTENTS I-III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII the centerpiece for the YoU, this tweets – the actual archive, as well Introduction retrospective affords pride of place as the visualization thereof, leaves I But who are all those people, to the sixteen twitter chats that much to be desired as a reading CHAL- dropped into the text by not these digitial publications inspired. copy. LENGEYOU much more than their names, During these chats, Joyceans of TO MAKE rapidly sketched features, ges- all stripes took to twitter to debate INSTANT tures, appearances and fragmen- and discuss the finer (and, at times, tary reactions? rougher) points of each episode; in SENSE OF THIS the hopes of celebrating as well as continuing the dialogue of YoU, these twitter chats are here pre- sented, with some editorial over- Does this relentlessly paran- Celebrating the 90th birthday sight, for your reading pleasure. tactical listing aggregate into of James Joyce’s Ulysses and its Prior to a brief discussion on anything with a claim to being incumbent Canadian emancipa- the necessity of this editorial understood as a narrative. In tion from copyright, the Year of engagement, I would like to thank #YoU Twitter Viz. Click to Enlarge. their sequence, the terse state- Ulysses (YoU) brought Joyce’s Dr. Jentery Sayer’s for his work in Warning: Bandwith Required ments appear as randomly masterpiece to the greatest possi- setting up an active twitter archive. -

Novelty and Canonicity in Lucian's Verae Historiae

Parody and Paradox: Novelty and Canonicity in Lucian’s Verae Historiae Katharine Krauss Barnard College Comparative Literature Class of 2016 Abstract: The Verae historiae is famous for its paradoxical claim both condemning Lucian’s literary predecessors for lying and also confessing to tell no truths itself. This paper attempts to tease out this contradictory parallel between Lucian’s own text and the texts of those he parodies even further, using a text’s ability to transmit truth as the grounds of comparison. Focusing on the Isle of the Blest and the whale episodes as moments of meta-literary importance, this paper finds that Lucian’s text parodies the poetic tradition for its limited ability to transmit truth, to express its distance from that tradition, and yet nevertheless to highlight its own limitations in its communication of truth. In so doing, Lucian reflects upon the relationship between novelty and adherence to tradition present in the rhetoric of the Second Sophistic. In the prologue of his Verae historiae, Lucian writes that his work, “τινα…θεωρίαν οὐκ ἄµουσον ἐπιδείξεται” (1.2).1 Lucian flags his work as one that will undertake the same project as the popular rhetorical epideixis since the Verae historiae also “ἐπιδείξεται.” Since, as Tim Whitmarsh writes, “sophistry often privileges new ideas” (205:36-7), Lucian’s contemporary audience would thus expect his text to entertain them at least in part through its novelty. Indeed, the Verae historiae fulfills these expectations by offering a new presentation of the Greek literary canon. In what follows I will first explore how Lucian’s parody of an epic katabasis in the Isle of the Blest episode criticizes the ability of the poetic tradition to transmit truth. -

Kalasiris and Charikleia: Mentorship and Intertext in Heliodorus' Aithiopika

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2017 Kalasiris and Charikleia: Mentorship and Intertext in Heliodorus' Aithiopika Lauren Jordan Wood College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Wood, Lauren Jordan, "Kalasiris and Charikleia: Mentorship and Intertext in Heliodorus' Aithiopika" (2017). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1004. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1004 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kalasiris and Charikleia: Mentorship and Intertext in Heliodorus’ Aithiopika A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Classical Studies from The College of William and Mary by Lauren Wood Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ William Hutton, Director ________________________________________ Vassiliki Panoussi ________________________________________ Suzanne Hagedorn Williamsburg, VA April 17, 2017 Wood 2 Kalasiris and Charikleia: Mentorship and Intertext in Heliodorus’ Aithiopika Odyssean and more broadly Homeric intertext figures largely in Greco-Roman literature of the first to third centuries AD, often referred to in scholarship as the period of the Second Sophistic.1 Second Sophistic authors work cleverly and often playfully with Homeric characters, themes, and quotes, echoing the traditional stories in innovative and often unexpected ways. First to fourth century Greek novelists often play with the idea of their protagonists as wanderers and exiles, drawing comparisons with the Odyssey and its hero Odysseus. -

Open Skoutelas Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS & ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN STUDIES THE CARTOGRAPHY OF POWER IN GREEK EPIC: HOMER’S ODYSSEY & THE RECEPTION OF HOMERIC GEOGRAPHIES IN THE HELLENISTIC AND IMPERIAL PERIODS CHARISSA SKOUTELAS SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Classics & Ancient Mediterranean Studies and Global & International Studies with honors in Classics & Ancient Mediterranean Studies Reviewed and approved* by the following: Anna Peterson Tombros Early Career Professor of Classical Studies and Assistant Professor of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Thesis Supervisor Erin Hanses Lecturer in Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Honors Adviser * Electronic approvals are on file. i ABSTRACT As modern scholarship has transitioned from analyzing literature in terms of its temporal components towards a focus on narrative spaces, scholars like Alex Purves and Donald Lateiner have applied this framework also to ancient Greek literature. Homer’s Odyssey provides a critical recipient for such inquiry, and Purves has explored the construction of space in the poem with relation to its implications on Greek epic as a genre. This paper seeks to expand upon the spatial discourse on Homer’s Odyssey by pinpointing the modern geographic concept of power, tracing a term inspired by Michael Foucault, or a “cartography of power,” in the poem. In Chapter 2 I employ a narratological approach to examine power dynamics played out over specific spaces of Odysseus’ wanderings, and then on Ithaca, analyzing the intersection of space, power, knowledge, and deception. The second half of this chapter discusses the threshold of Odysseus’ palace and flows of power across spheres of gender and class. -

Trevino Uchicago 0330D 14659.Pdf

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO INSPIRATION AND NARRATIVE IN THE HOMERIC ODYSSEY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS BY NATALIE TREVINO CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MARCH 2019 Contents LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................ v ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................. vii INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 I.1 Innovation, Aberration, and Metanarrative ............................................................................ 1 I.2 Scholarly Opinions, A History of Devaluation ...................................................................... 2 I.3 Decoding the Inscrutable: Genre, Inspiration, and The Poet ................................................. 6 I.4 Methodology: Studies in the Inspiration of Poets and Prophets, and Narratology .............. 14 I.5 Chapter Summaries .............................................................................................................. 18 I.6 Glossary ..............................................................................................................................