JACQUES ROUSSEAU's EMILE By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sovereignty of the Living Individual: Emerson and James on Politics and Religion

religions Article Sovereignty of the Living Individual: Emerson and James on Politics and Religion Stephen S. Bush Department of Religious Studies, Brown University, 59 George Street, Providence, RI 02912, USA; [email protected] Received: 20 July 2017; Accepted: 20 August 2017; Published: 25 August 2017 Abstract: William James and Ralph Waldo Emerson are both committed individualists. However, in what do their individualisms consist and to what degree do they resemble each other? This essay demonstrates that James’s individualism is strikingly similar to Emerson’s. By taking James’s own understanding of Emerson’s philosophy as a touchstone, I argue that both see individualism to consist principally in self-reliance, receptivity, and vocation. Putting these two figures’ understandings of individualism in comparison illuminates under-appreciated aspects of each figure, for example, the political implications of their individualism, the way that their religious individuality is politically engaged, and the importance of exemplarity to the politics and ethics of both of them. Keywords: Ralph Waldo Emerson; William James; transcendentalism; individualism; religious experience 1. Emersonian Individuality, According to James William James had Ralph Waldo Emerson in his bones.1 He consumed the words of the Concord sage, practically from birth. Emerson was a family friend who visited the infant James to bless him. James’s father read Emerson’s essays out loud to him and the rest of the family, and James himself worked carefully through Emerson’s corpus in the 1870’s and then again around 1903, when he gave a speech on Emerson (Carpenter 1939, p. 41; James 1982, p. 241). -

Jacques-Louis David

Jacques-Louis David THE FAREWELL OF TELEMACHUS AND EUCHARIS Jacques-Louis David THE FAREWELL OF TELEMACHUS AND EUCHARIS Dorothy Johnson GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART Los ANGELES For my parents, Alice and John Winter, and for Johnny Christopher Hudson, Publisher Cover: Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748 — 1825). The Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis, 1818 Benedicte Gilman, Editor (detail). Oil on canvas, 87.2 x 103 cm (34% x 40/2 in.). Elizabeth Burke Kahn, Production Coordinator Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum (87.PA.27). Jeffrey Cohen, Designer Lou Meluso, Photographer Frontispiece: (Getty objects, 87.PA.27, 86.PA.740) Jacques-Louis David. Self-Portrait, 1794. Oil on canvas, 81 x 64 cm (31/8 x 25/4 in.). Paris, © 1997 The J. Paul Getty Museum Musee du Louvre (3705). © Photo R.M.N. 17985 Pacific Coast Highway Malibu, California 90265-5799 All works of art are reproduced (and photographs Mailing address: provided) courtesy of the owners, unless otherwise P.O. Box 2112 indicated. Santa Monica, California 90407-2112 Typography by G&S Typesetters, Inc., Library of Congress Austin, Texas Cataloging-in-Publication Data Printed by C & C Offset Printing Co., Ltd., Hong Kong Johnson, Dorothy. Jacques-Louis David, the Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis / Dorothy Johnson, p. cm.—(Getty Museum studies on art) Includes bibliographical references (p. — ). ISBN 0-89236-236-7 i. David, Jacques Louis, 1748 — 1825. Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis. 2. David, Jacques Louis, 1748-1825 Criticism and interpretation. 3. Telemachus (Greek mythology)—Art. 4. Eucharis (Greek mythology)—Art. I. Title. -

The Abolition of Emerson: the Secularization of America’S Poet-Priest and the New Social Tyranny It Signals

THE ABOLITION OF EMERSON: THE SECULARIZATION OF AMERICA’S POET-PRIEST AND THE NEW SOCIAL TYRANNY IT SIGNALS A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government By Justin James Pinkerman, M.A. Washington, DC February 1, 2019 Copyright 2019 by Justin James Pinkerman All Rights Reserved ii THE ABOLITION OF EMERSON: THE SECULARIZATION OF AMERICA’S POET-PRIEST AND THE NEW SOCIAL TYRANNY IT SIGNALS Justin James Pinkerman, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Dr. Richard Boyd, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Motivated by the present climate of polarization in US public life, this project examines factional discord as a threat to the health of a democratic-republic. Specifically, it addresses the problem of social tyranny, whereby prevailing cultural-political groups seek to establish their opinions/sentiments as sacrosanct and to immunize them from criticism by inflicting non-legal penalties on dissenters. Having theorized the complexion of factionalism in American democracy, I then recommend the political thought of Ralph Waldo Emerson as containing intellectual and moral insights beneficial to the counteraction of social tyranny. In doing so, I directly challenge two leading interpretations of Emerson, by Richard Rorty and George Kateb, both of which filter his thought through Friedrich Nietzsche and Walt Whitman and assimilate him to a secular-progressive outlook. I argue that Rorty and Kateb’s political theories undercut Emerson’s theory of self-reliance by rejecting his ethic of humility and betraying his classically liberal disposition, thereby squandering a valuable resource to equip individuals both to refrain from and resist social tyranny. -

Lesson Plan Template

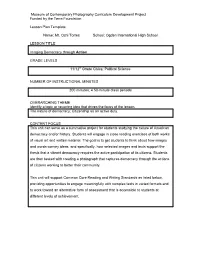

Museum of Contemporary Photography Curriculum Development Project Funded by the Terra Foundation Lesson Plan Template Name: Mr. Ozni Torres School: Ogden International High School LESSON TITLE Imaging Democracy through Action GRADE LEVELS 11/12th Grade Civics; Political Science NUMBER OF INSTRUCTIONAL MINUTES 200 minutes; 4 50-minute class periods OVERARCHING THEME Identify a topic or recurring idea that drives the focus of the lesson. The nature of democracy; Citizenship as an active duty. CONTENT FOCUS This unit can serve as a summative project for students studying the nature of American democracy and/or history. Students will engage in close reading exercises of both works of visual art and written material. The goal is to get students to think about how images and words convey ideas, and specifically, how selected images and texts support the thesis that a vibrant democracy requires the active participation of its citizens. Students are then tasked with creating a photograph that captures democracy through the actions of citizens working to better their community. This unit will support Common Core Reading and Writing Standards as listed below, providing opportunities to engage meaningfully with complex texts in varied formats and to work toward an alternative form of assessment that is accessible to students at different levels of achievement. Museum of Contemporary Photography Curriculum Development Project Funded by the Terra Foundation ART ANALYSIS List the names of artist(s) and titles of their artwork that students will do close reading exercises on. Artist Work of Art John Trumbull 12’ X 18’ 1818 Rotunda; U.S. Capitol D eclaration of Independence Paul Shambroom 2’9” X 5’6” 1999 Museum of Contemporary Photography Markl e, IN (pop. -

ED331751.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 331 751 SO 020 969 AUTHOR Brooks, B. David TITLE Success through Accepting Responsibility. Principal's Handbook: Creating a School Climate of Responsibility. Revised Edition. INSTITUTION Thomas Jefferson Research Center, Pasadena, Calif. PUB DATE 89 NOTE 130p. AVAILABLE FROM Thomas Jefferson Research Center, 202 South Lake Avenue, Suite 240, Pasadena, CA 91101. PUB TYPE Guides - Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Administrator Guides; *Administrator Role; Citizenship Education; *Educational Environment; Educational Planning; Elementary Secondary Education; Ethics; *pri4cipals; School Activities; Self Esteem; Skill Development; Social Responsibility; Social Studies; *Student Educational Objectives; *Student Responsibility; *Success; Values; Vocabulary Development ABSTRACT Success Through Accepting Responsibility (STAR)is primarily a language program, although the valueshave a relationship to social studies topics. Through language developmentthe words, concepts, and skills of personal responsibilitymay be taught. This principal's handbook outlines a school-wide systematicapproach for building a positive school climate around self-esteemand personal responsibility. Following an introduction, the handbookis organized into eight sections: planning and implementation;kick-off activities; year-long activities; sustainingevents and activities; end-of-year activities; parent and communityinvolvement; evaluations and reports; and principal's memos. (DB) ** ***** **************************************************************** -

God Within": the Experience and Manifestation of Emerson's Evolving Philosophy of Intuition

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2014-05-21 Discovering the "God Within": The Experience and Manifestation of Emerson's Evolving Philosophy of Intuition Anne Tiffany Turner Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Turner, Anne Tiffany, "Discovering the "God Within": The Experience and Manifestation of Emerson's Evolving Philosophy of Intuition" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 4099. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4099 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Discovering the “God Within”: The Experience and Manifestation of Emerson’s Evolving Philosophy of Intuition Anne Turner A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Edward Cutler, Chair Jesse Crisler Emron Esplin Department of English Brigham Young University April 2014 Copyright © 2014 Anne Turner All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Discovering the “God Within”: The Experience and Manifestation of Emerson’s Evolving Philosophy of Intuition Anne Turner Department of English, BYU Master of Art Investigating individual subjectivity, Ralph Waldo Emerson traveled to Europe following the death of his first wife, Ellen Tucker Emerson, and his resignation from the Unitarian ministry. His experience before and during the voyage contributed to the evolution of a self-intuitive philosophy, termed selbstgefühl by the German Romantics and altered his careful style of composition and delivery to promote the integrity of individual subjectivity as the highest authority in the deduction of truth. -

Graduate Seminar in American Political Thought University of Washington Autumn 2020 5 Credits Wednesday, 1:30-4:20 P.M

DEMOCRACY AS A WAY OF LIFE Political Science 516: Graduate Seminar in American Political Thought University of Washington Autumn 2020 5 Credits Wednesday, 1:30-4:20 p.m. Remote Learning Version Course Website: https://canvas.uw.edu/courses/1401667 Jack Turner 133 Gowen [email protected] Office Hours: By appointment DESCRIPTION Democracy is often conceived of as a mode of government or form of rule, but both advocates and critics of democracy have just as frequently emphasized its significance as a social and cultural way of life, a manner of being in the world. Plato called democracy “the most attractive of the regimes . like a coat of many colors”; he also worried how democracy toppled the most basic relations of authority. Children defy their parents in a democracy, and students their teachers. Horses and donkeys wander “the streets with total freedom, noses in the air, barging into any passer-by who fails to get out of the way.” This seminar analyzes democracy as a distinctive way of life as it arose after the American, French, and Haitian Revolutions. It begins with the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century transatlantic debates about the meaning of democratic revolution (Edmund Burke and Thomas Paine), segues to the flowering of democratic culture in the United States and its relationship to white supremacy (David Walker, Alexis de Tocqueville, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau), examines the nature of democratic education, popular sovereignty, and racial violence in mass, industrializing society (John Dewey and Ida B. Wells), and probes the connections between democracy, race, and empire in the twentieth century (W.E.B. -

Reflections on Student Being and Becoming in the Contemporary

applyparastyle “fig//caption/p[1]” parastyle “FigCapt” 2020 00 03 1 Introduction: Reflections on 9 Student Being and Becoming © 2020 in the Contemporary University 2020 AMANDA J. FULFORD Edge Hill University What is it to be a student in the contemporary university? How does one become a student, and is being a student simply the result of registering with a particular institution? What does (or should) a student do? Does she sim- ply study, or how else is the “being” of a student expressed? Of course, these questions may seem simple to answer, at least on one level. They are questions that go to the heart of the motivations and practices of the academic’s work in lecturing and supporting students in higher education. They are also ques- tions that, in some ways at least, are the concern of those with responsibility for managing, leading, funding and regulating higher education. But this edition seeks to move beyond such apparently obvious answers, and to con- sider again what might be at stake in the idea of student being and becoming. This special edition, on the theme of “Student Being and Becoming” came about following the annual conference of the Philosophy and Theory of Higher Education Society (PaTHES) on the same theme. This was held at Middlesex University, London, in 2018. The theme was selected at the previous year’s conference in Denmark, partly, at least, because there is much potential in bringing philosophy and theory to bear on matters relating to the student—and being and becoming a student—in the contemporary university. -

The Cases of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Edgar Allan Poe Dissertation P

THE MIDDLE EAST IN ANTEBELLUM AMERICA: THE CASES OF RALPH WALDO EMERSON, NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE, AND EDGAR ALLAN POE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ahmed Nidal Almansour ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Steven S. Fink, Adviser Professor Jared Gardner _______________________ Professor Elizabeth Hewitt Adviser English Copyright by Ahmed Nidal Almansour 2005 ABSTRACT The presence of the Middle East in the works of American artists between the Revolution and the Civil War is pervasive and considerable. What makes this outlandish element of critical significance is that its proliferation coincided with the emerging American literary identity. The wide spectrum of meanings that was related to it adds even more significance to its critical value. In its theoretical approach, this work uses Raymond Schwab’s The Oriental Renaissance as a ground for all its arguments. It considers the rise of the Oriental movement in America to be a continuation of what had already started of Oriental researches in Europe. Like their counterparts in Europe, the American writers who are selected for this study were genuinely interested in identifying with the Oriental thought. The European mediation, however, should not be allowed to hold any significance other than pointing to the fact that French, German, and English Orientalist organizations were more technically equipped. The sentiment of identification with the East resonated equally on both sides of the Atlantic. This work investigates three cases from antebellum America: Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Edgar Allan Poe. -

JS Mill's Political Thought

P1: JZZ 0521860202pre CUFX079B/Urbinati 0 521 86020 2 cupusbw December 26, 2006 7:38 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: JZZ 0521860202pre CUFX079B/Urbinati 0 521 86020 2 cupusbw December 26, 2006 7:38 J. S. MILL’S POLITICAL THOUGHT The year 2006 marked the two hundredth anniversary of John Stuart Mill’s birth. Although his philosophical reputation has varied greatly in the interven- ing years, it is now clear that Mill ranks among the most influential modern political thinkers. Yet despite his enduring influence, and perhaps also because of it, the breadth and complexity of Mill’s political thought is often under- appreciated. Although his writings remain a touchstone for debates over liberty and liberalism, many other important dimensions of his political philosophy have until recently been mostly ignored or neglected. This volume aims, first, to correct such neglect by illustrating the breadth and depth of Mill’s political writings. It does so by drawing togetheracollection of essays whose authors explore underappreciated elements of Mill’s political philosophy, including his democratic theory, his writings on international relations and military inter- ventions, and his treatments of socialism and despotism. Second, the volume shows how Mill’s thinking remains pertinent to our own political life in three broad areas – democratic institutions and culture, liberalism, and international politics – and offers a critical reassessment of Mill’s political philosophy in light of recent political developments and transformations. Nadia Urbinati -

"The Odyssey"And Soyinka^S "The Bacchae of Euripides"

Cross-Cultural Dialogues with Greek Classics: Walcotù "The Odyssey"and Soyinka^s "The Bacchae of Euripides" VALÉRIE BADA D EREK WALCOTT'S The Odyssey and Wole Soyinka's The Bacchae of Euripides represent creative attempts to revitalise Western canonical works by offering a visionary reconstruction of subterranean mythic recurrences through a creolization rooted in Caribbean folklore, on the one hand, and an explora• tion of the myth of Dionysos in the light of Yoruba cosmology on the other. This imaginative reshaping of literary and reli• gious myths does not so much betray a need for classical valida• tion as it reveals a comparative scrutinising of archetypal patterns in order to disclose "latent cross-culturalities" (Harris, "Quetzalcoatl" 40, qtd. in Maesjelinek 37), that is, a subterra• nean cross-cultural polyphonic structure. Homer's epic and Euripides' play appear as palimpsests constantly disrupted by overarching textual revisions entirely written in the spaces be• tween the Greek words. The revelation of cross-cultural streams of myths, concepts and symbols underscores the regenerative potentiality of the original literary paradigms whose latent am• biguity, shifting meaning and archetypal qualities define them as poetic sites particularly open to creative alterations. Walcott's and Soyinka's plays reveal an unrelenting obsession with myth and make clear its complex interaction with history. The two playwrights' poetic imagination is constantly immersed in currents of change by crossing mythological archetypes (Car• ibbean, Yoruba and European) with fresh historical insights and by bringing myths "into explosive contact with the rawness of the present" (Moore 169). This reactivation and creative ARIEL: A Review of International English Literature, 31:3, July 2000 8 VALÉRIE BADA mutation of mythological themes reveal the two poets as both users and creators of myths: their imagination is both rooted in mythic grounds and involved in a mythopoeic dynamics of cul• tural cross-fertilization. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses `Dangerous Creatures': Selected children's versions of Homer's Odyssey in English 16992014 RICHARDS, FRANCESCA,MARIA How to cite: RICHARDS, FRANCESCA,MARIA (2016) `Dangerous Creatures': Selected children's versions of Homer's Odyssey in English 16992014 , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11522/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 ‘Dangerous Creatures’: Selected children’s versions of Homer’s Odyssey in English 1699–2014 Abstract This thesis considers how the Odyssey was adapted for children, as a specific readership, in English literature 1699-2014. It thus traces both the emergence of children’s literature as a publishing category and the transformation of the Odyssey into a tale of adventure – a perception of the Odyssey which is still widely accepted today (and not only among children) but which is not, for example, how Aristotle understood the poem.