The 1848 Conflicts and Their Significance in Swiss Historiography Thomas Maissen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Il Generale Henri Guisan

Il Generale Henri Guisan Autor(en): Fontana Objekttyp: Obituary Zeitschrift: Rivista militare della Svizzera italiana Band (Jahr): 32 (1960) Heft 3 PDF erstellt am: 26.09.2021 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch RIVISTA MILITARE DELLA SVIZZERA ITALIANA Anno XXXII - Fascicolo III Lugano, maggio - giugno 1960 REDAZIONE : Col. Aldo Camponovo. red. responsabile; Col. Ettore Moccetti; Col. S.M.G. Waldo Riva AMMINISTRAZIONE : Cap. Neno Moroni-Stampa, Lugano Abbonamento: Svizzera un anno fr. 6 - Estero fr. 10,- - C.to ch. post. XI a 53 Inserzioni: Annunci Svizzeri S.A. «ASSA», Lugano, Bellinzona. Locamo e Succ, Il Generale Henri Guisan / Il 7 aprile all'età di 86 anni è deceduto a Pully, dopo breve malattia, il Generale Guisan, Comandante in Capo dell'Esercito Svizzero durante la seconda guerra mondiale. -

Ried Bei Kerzers Prop. Statistique Répartition Des Sièges Et

Répartition des sièges et pourcentage Commune Ried bei Kerzers See / Lac Election du Grand Conseil du 6 novembre 2016 — Liste no Sigle Suffrages de parti Pourcentage 1 PDC 126 3.6% 2 PS Lac 402 11.5% 3 PLR 1'105 31.5% 5 UDC 1'682 48.0% 6 PVL 189 5.4% Total 3'504 100.0% http://www.fr.ch/ 07.11.2016 / 00:06:26 Données fournies sans aucune garantie 1 / 11 Répartition des sièges et pourcentage Commune Ried bei Kerzers See / Lac Election du Grand Conseil du 6 novembre 2016 — Parti Démocrate-Chrétien (PDC) Liste 1 Sigle PDC Suffrages nominatifs 122 Suffrages complémentaires 4 Suffrages de parti 126 Rang Nom Prénom Ann. naiss. Profession Domicile suffrages Sort. Ont obtenu des voix: 1 Hecht Urs 1965 Chef de projet DDPS / Projektleiter VBS Kerzers 32 Indépendante, conseillère bso & formatrice 2 Aebischer Susanne 1976 d'adultes / Selbständige Beraterin bso & Kerzers 24 x Erwachsenenbildnerin Secrétaire, femme au foyer / Sekretärin, 3 Roche-Etter Doris 1961 Wallenried 11 Hausfrau Enseignante spécialisée / 4 Hayoz Madeleine 1955 Cressier 10 x Sonderpädagogin 5 Sciboz Jean-Marc 1965 Gérant d'affaires / Geschäftsführer Guschelmuth 10 6 Keller Etel 1966 Ing. Agronome EPFZ / Ing. Agronom ETH Murten 7 Technicienne en salle d'opération TSO / 7 Vogel Nadine 1968 Wallenbuch 7 Technische Operationsassistentin TOA lic. iur. utr., avocat / lic. iur. utr., 8 Moser Jacques 1971 Murten 6 Rechtsanwalt 9 König Marina 1994 Interactive Media Designer Courgevaux 5 http://www.fr.ch/ 07.11.2016 / 00:06:26 Données fournies sans aucune garantie 2 / 11 Répartition des sièges et pourcentage Commune Ried bei Kerzers See / Lac Election du Grand Conseil du 6 novembre 2016 — Ont obtenu des voix: Ing. -

International Review of the Red Cross, March 1963, Third Year

MARCH 1963-THIRD YEAR-No. 24 International Review of the Red Cross CENTENARY YEAR OF TllE RED CROSS 1963 PftOPERTY OF u.s. ARMY me JUDGE ADVOCATE GENERAl'S SCHOOL LI8RAAY GENEVA INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE RED CROSS FOUNDED IN 1863 INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE RED CROSS LEOPOLD BOISSIER, Doctor of Laws, HonoraryProfessor at the Universityof Geneva, for mer Secretary-General to the Inter-Parliamentary Union, President (member since 1946) JACQUES CHENEVIERE, Hon. Doctor of Literature, Honorary Vice-President (1919) CARL]. BURCKHARDT, Doctor of Philosophy, former Swiss Minister to France (1933) MARTIN BODMER, Hon. Doctor of Philo~ophy, Vice-President (1940) ERNEST GLOOR, Doctor (1945) PAUL RUEGGER, former Swiss Minister to Italy and the United Kingdom, Member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (1948) RODOLFO OLGIATI, Hon. Doctor of Medicine, former Director of the Don Suisse (1949) MARGUERITE VAN BERCHEM, former Head of Section, Central Prisoners of War Agency (1951) FREDERIC SIORDET, Lawyer, Counsellor of the International Committee of the Red Cross from 1943 to 1951, Vice-President (1951) GUILLAUME BORDIER, Certificated Engineer E.P.F., M.B.A. Harvard, Banker (1955) ADOLPHE FRANCESCHETTI, Doctor of Medicine, Professor of clinical ophthalmology at Geneva University (1958) HANS BACHMANN, Doctor of Laws, Assistant Secretary-General to the International Committee of the Red Cross from 1944 to 1946 (1958) JACQUES FREYMOND, Doctor of Literature, Director of the Graduate Institute of International Studies, Professor at the University of Geneva (1959) DIETRICH SCHINDLER, Doctor of Laws (1961) SAMUEL GONARD, former Colonel Commanding an Army Corps, former Professor at the Federal Polytechnical School (1961) HANS MEULI, Doctor of Medicine, Brigade Colonel, former Director of the Swiss Army Medical Service (1961) MARJORIE DUVILLARD, Directress of" Le Bon Secours" Nursing School (1961) MAX PETITPIERRE, Doctor of Laws, former President of the Swiss Confederation (1961) Honorary membeT~ : Miss LUCIE ODIER, Honorary Vice-President. -

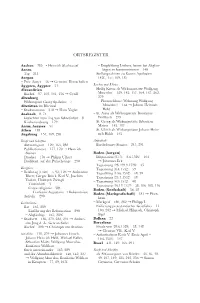

Ortsregister

OrtsregIster Aachen—285 → heinrich slachtscaef – empfehlung luthers, besser bei altgläu- Aarau bigen zu kommunizieren—140 – tag—211 – stellungnahmen zu Bucers apologien— Aargau 142f., 157, 169, 187 – Freie Ämter—36 → gemeine herrschaften Ägypten, Ägypter—51 Kirchen und Klöster Alexandrien – heilig Kreuz als Wirkungsstätte Wolfgang – Bischof—97, 102, 141, 156 → cyrill Musculus’—129, 142, 157, 164, 187, 262, Altenburg 279 – Wirkungsort georg spalatins—7 – Pfarrzechhaus (Wohnung Wolfgang Altstätten im rheintal Musculus’)—164 → Johann heinrich – stadtammann—218 → hans vogler held Ansbach—8, 74 – st. anna als Wirkungsstätte Bonifatius – gutachten zum tag von schweinfurt—8 Wolfharts—279 – Kirchenordnung—179 – st. georg als Wirkungsstätte sebastian Assur, Assyrer—51 Maiers—143, 187 Athen—158 – st. ulrich als Wirkungsstätte Johann hein- Augsburg—157, 169, 290 rich helds—163 Briefe und Schriften Aufenthalt – abfassungsort—129, 163, 288 – Bartholomeo Fonzios—243, 291 – Publikationsort—157, 170 → heinrich steiner Baden (Aargau) – Drucker—170 → Philipp ulhart – Disputation (21.5. – 8.6.1526)—101 – Drohbrief auf der Perlachstiege—290 → Johannes eck – tagsatzung (28./29.9.1528)—35 Ereignisse – tagsatzung (8.4.1532)—59 – reichstag (1530)—5, 92, 126 → ambrosius – tagsatzung (10.6.1532)—48, 59 Blarer, gregor Brück, Karl v., Joachim – tagsatzung (23.7.1532)—48 vadian, huldrych zwingli – tagsatzung (4.9.1532)—48 – türkenhilfe—5 – tagsatzung (16.12.1532)—38, 106–108, 116 – causa religionis—38f. Baden (Grafschaft)—36, 58 – confessio augustana Bekenntnisse → Baden (Markgrafschaft)—181 → Pforz- – aufruhr—290 heim Institutionen – Markgraf—180, 282 → Philipp I. – rat—165, 289 – exilierung protestantischer geistlicher—11, – einführung der reformation—290 180, 282 → Michael hilspach, christoph – altgläubige—165, 289f. sigel – stadtarzt—186, 279, 288, 291 → ambro- Balkan—22 sius Jung d. -

Horaires Et Trajet De La Ligne 546 De Bus Sur Une Carte

Horaires et plan de la ligne 546 de bus 546 Courtepin Gare Voir En Format Web La ligne 546 de bus (Courtepin Gare) a 2 itinéraires. Pour les jours de la semaine, les heures de service sont: (1) Courtepin Gare: 06:46 - 17:46 (2) Murten/Morat Bahnhof: 07:52 - 18:22 Utilisez l'application Moovit pour trouver la station de la ligne 546 de bus la plus proche et savoir quand la prochaine ligne 546 de bus arrive. Direction: Courtepin Gare Horaires de la ligne 546 de bus 9 arrêts Horaires de l'Itinéraire Courtepin Gare: VOIR LES HORAIRES DE LA LIGNE lundi 06:46 - 17:46 mardi 06:46 - 17:46 Murten/Morat Bahnhof 8 Erlachstrasse, Murten mercredi 06:46 - 17:46 Murten Orientierungsschule jeudi 06:46 - 17:46 Murten Neugut vendredi 06:46 - 17:46 2 Neugut, Murten samedi Pas opérationnel Münchenwiler Dorf dimanche Pas opérationnel 1 Bahnhofstrasse, Münchenwiler Münchenwiler Bahnhof 31 Bruyère, Münchenwiler Informations de la ligne 546 de bus Courgevaux Village Direction: Courtepin Gare 3 Chemin De l'Ancienne Poste, Courgevaux Arrêts: 9 Durée du Trajet: 20 min Courlevon Dorf Récapitulatif de la ligne: Murten/Morat Bahnhof, 25 Hauptstrasse, Courlevon Murten Orientierungsschule, Murten Neugut, Münchenwiler Dorf, Münchenwiler Bahnhof, Wallenried Village Courgevaux Village, Courlevon Dorf, Wallenried 3 Route de Grand-Clos, Wallenried Village, Courtepin Gare Courtepin Gare 10 Route De Fribourg, Courtepin Direction: Murten/Morat Bahnhof Horaires de la ligne 546 de bus 9 arrêts Horaires de l'Itinéraire Murten/Morat Bahnhof: VOIR LES HORAIRES DE LA LIGNE lundi -

International Review of the Red Cross, February 1976, Sixteenth Year

FEBRUARY 1976 SIXTEENTH YEAR - No. 179 international review• of the red cross PROPERTY OF U.S. ARMY INTER ARMA CARITAS THE JUDGE ADVOCATE GENERAL'S SCHOOL LIBRARY GENEVA INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE REO CROSS FOUNOEO IN 1863 INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE RED CROSS Mr. ERIC MARTIN, Doctor of Medicine, Honorary Professor ofthe University ofGeneva, President (member since 1973) Mr. JEAN PICTET, Doctor of Laws, Chairman of the Legal Commission, Director of the Henry-Dunant Institute, Associate Professor at the University of Geneva, Vice-President (1967) Mr. HARALD HUBER, Doctor of Laws, Federal Court Judge, Vice-President (1969) Mrs. DENISE BINDSCHEDLER-ROBERT, Doctor of Laws, Professor at the Graduate Institute of International Studies, Geneva, Judge at the European Court of Human Rights (1967) Mr. MARCEL A. NAVILLE, Master of Arts, ICRC President from 1969 to 1973 (1967) Mr. JACQUES F. DE ROUGEMONT, Doctor of Medicine (1967) Mr. ROGER GALLOPIN, Doctor of Laws, former ICRC Director-General (1967) Mr. WALDEMAR JUCKER, Doctor of Laws, Secretary, Union syndicale suisse (1967) Mr. VICTOR H. UMBRICHT, Doctor of Laws, Managing Director (1970) Mr. PIERRE MICHELI, Bachelor of Laws, former Ambassador (1971) Mr. GILBERT ETIENNE, Professor at the Graduate Institute of International Studies and at the Institut d'etudes du developpement, Geneva (1973) Mr. ULRICH MIDDENDORP, Doctor of Medicine, head of surgical department of the Cantonal Hospital, Winterthur (1973) Mrs. MARION BOVEE-ROTHENBACH, Master of Social Work (University ofMichigan), Reader at the Ecole des Sciences sociales et politiques of the University of Lausanne (1973) Mr. HANS PETER TSCHUDI, Doctor of Laws, former Swiss Federal Councillor (1973) Mr. -

Vorlage Web-Dokus

Inhalt mit Laufzeit Geschichte für Sek I und Sek II Deutsch Der General Die Lebensgeschichte Henri Guisans 55:15 Minuten 00:00 Kurz vor Ausbruch des Zweiten Weltkrieges wählt die Bun- desversammlung Guisan zum General. 04:19 Im September 1939 erklärt Hitler Polen den Krieg. Darauf rücken 600'000 Schweizer Männer bei der Generalmobilmachung in den Aktivdienst ein. 07:01 General Henri Guisan kommt 1874 als Sohn eines Landarz- tes zur Welt. Er schliesst erfolgreich sein Agronomiestudium ab. Den Militärdienst leistet er bei der Kavallerie. Bereits während des Ersten Weltkriegs ist er Mitglied des Generalstabs. 11:56 Guisans politische Einstellung ist rechts-konservativ. Deshalb pflegt er enge Verbindungen zur liberalen Partei. Während des lan- desweiten Generalstreiks 1918 leitet Guisan ein Regiment in Zürich. 13:11 1934 trifft er Benito Mussolini, zu dem er ein freundschaftli- ches Verhältnis aufbaut. Guisan hofft, dass Mussolini Hitler von ei- nem Angriff auf die Schweiz abhalten kann. Sein erstes Hauptquar- tier ist das Schloss Gümligen. Mitarbeiter des persönlichen Stabs steuern den Personenkult um Guisan. 19:18 Anscheinend verspricht die französische Militärspitze Hilfe im Falle eines Angriffs von Deutschland. Die Eroberung von Paris zer- stört jedoch diese Hoffnung. Einzig Grossbritannien leistet Hitler noch Widerstand. In dieser Phase ist das Verhältnis zwischen Bun- despräsident Pilet-Golaz und Guisan angespannt. 23:47 Guisan beordert 650 Offiziere aufs Rütli zum Rapport. Dort bekräftigt er den Verteidigungswillen. Mit dem Rückzug ins Réduit konzentriert er seine Verteidigung auf die Alpenregion. Haben die Deutschen deshalb nicht angegriffen? Historiker bezweifeln heute diese Theorie. 28:07 Viele Flüchtlinge suchen während dieser Zeit Schutz in der Schweiz. -

Gotthard Panorama Express. Sales Manual 2021

Gotthard Panorama Express. Sales Manual 2021. sbb.ch/en/gotthard-panorama-express Enjoy history on the Gotthard Panorama Express to make travel into an experience. This is a unique combination of boat and train journeys on the route between Central Switzerland and Ticino. Der Gotthard Panorama Express: ì will operate from 1 May – 18 October 2021 every Tuesday to Sunday (including national public holidays) ì travels on the line from Lugano to Arth-Goldau in three hours. There are connections to the Mount Rigi Railways, the Voralpen-Express to Lucerne and St. Gallen and long-distance trains towards Lucerne/ Basel, Zurich or back to Ticino via the Gotthard Base Tunnel here. ì with the destination Arth-Goldau offers, varied opportunities; for example, the journey can be combined with an excursion via cog railway to the Rigi and by boat from Vitznau. ì runs as a 1st class panorama train with more capacity. There is now a total of 216 seats in four panorama coaches. The popular photography coach has been retained. ì requires a supplement of CHF 16 per person for the railway section. The supplement includes the compulsory seat reservation. ì now offers groups of ten people or more a group discount of 30% (adjustment of group rates across the whole of Switzerland). 2 3 Table of contents. Information on the route 4 Route highlights 4–5 Journey by boat 6 Journey on the panorama train 7 Timetable 8 Train composition 9 Fleet of ships 9 Prices and supplements 12 Purchase procedure 13 Services 14 Information for tour operators 15 Team 17 Treno Gottardo 18 Grand Train Tour of Switzerland 19 2 3 Information on the route. -

On the Way to Becoming a Federal State (1815-1848)

Federal Department of Foreign Affairs FDFA General Secretariat GS-FDFA Presence Switzerland On the way to becoming a federal state (1815-1848) In 1815, after their victory over Napoleon, the European powers wanted to partially restore pre-revolutionary conditions. This occurred in Switzerland with the Federal Pact of 1815, which gave the cantons almost full autonomy. The system of ruling cantons and subjects, however, remained abolished. The liberals instituted a series of constitutional reforms to alter these conditions: in the most important cantons in 1830 and subsequently at federal level in 1848. However, the advent of the federal state was preceded by a phase of bitter disputes, coups and Switzerland’s last civil war, the Sonderbund War, in 1847. The Congress of Vienna and the Restoration (1814–1830) At the Congress of Vienna in 1814 and the Treaty of Paris in 1815, the major European powers redefined Europe, and in doing so they were guided by the idea of restoration. They assured Switzerland permanent neutrality and guaranteed that the completeness and inviolability of the extended Swiss territory would be preserved. Caricature from the year 1815: pilgrimage to the Diet in Zurich. Bern (the bear) would like to see its subjects Vaud and Aargau (the monkeys) returned. A man in a Zurich uniform is pointing the way and a Cossack is driving the bear on. © Historical Museum Bern The term “restoration”, after which the entire age was named, came from the Bernese patrician Karl Ludwig von Haller, who laid the ideological foundations for this period in his book “Restoration of the Science of the State” (1816). -

Pionnier: Dufour Guillaume-Henri Dufour 1787

PIONNIER: DUFOUR (AUTEUR : ANTOINE WASSERFALLEN) GUILLAUME-HENRI DUFOUR 1787 - 1875 5.Dufour.FULL.1.JPEG SA VIE Guillaume-Henri Dufour naît le 15 septembre 1787 à Constance, où sa famille s’était réfugiée après les troubles de 1782 à Genève. La perte d’influence du parti aristocratique genevois une fois confirmée, notamment à cause de l’influence de la révolution française, la famille put retourner dans son foyer, et Guillaume-Henri aller en classe à Genève. Par la suite, il entre à « l’Ecole Polytechnique » de Paris, dans la section "pionniers", puis à Metz, à “l’Ecole d’application”, pour y étudier le génie des fortifications. Il quitte le service actif français en 1817 et prend à Genève le poste d’ingénieur cantonal, ce poste comprenant également les affaires militaires et l’urbanisme. Il fait en 1819 partie des cercles fondateurs de l’Ecole Militaire de Thoune. Nommé Quartier-Maître en chef, il lui échoit également la direction des missions de topographie. Il fonde le “Bureau Topographique Fédéral”, afin de mener à bien l’élaboration de l’atlas des cartes nationales. La guerre du Sonderbund le voit prendre la tête de l’armée Suisse en 1847, en tant que Général. © SATW ASST Commission “Histoire des Techniques” 1997-2001 PAGE 1 Basé sur les documents de l’ETHZ (EPFZ) - Institut für Verhaltenswissenschaft : Documentation et posters élaborés dans le cadre des cours du Prof. Dr. Karl Frey et Dr. Angela Frey-Eiling Formation des Professeurs de Gymnase, Direction Prof. Beat Fürer - PHS St.-Gall - juillet 1995. Schweizerische Akademie der Technischen Wissenschaft Académie Suisse des Sciences et Techniques 5.Dufour.1000.FR.doc PIONNIER: DUFOUR (AUTEUR : ANTOINE WASSERFALLEN) 5.Dufour.FULL.2.JPEG Original de la médaille commémorative ; cabinet des Médailles (Lausanne) L’atlas topographique, la première oeuvre cartographique complète de la Suisse, est terminé en 1865. -

Military Law Review

DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY PAMPHLET 27-1 00-21 MILITARY LAW REVIEW Articles KIDNAPPISG AS A 1IIILITARY OFFENSE Major hfelburn N. washburn RELA TI OX S HIP BETTYEE?; A4PPOISTED AND INDI T’IDUAL DEFENSE COUNSEL Lievtenant Commander James D. Nrilder COI~1KTATIONOF SIILITARY SENTENCES Milton G. Gershenson LEGAL ASPECTS OF MILITARY OPERATIONS IN COUNTERINSURGENCY Major Joseph B. Kelly SWISS MILITARY JUSTICE Rene‘ Depierre Comments 1NTERROC;ATION UNDER THE 1949 PRISOKERS OF TT-AR CON-EKTIO?; ONE HLSDREClTH ANNIS’ERSARY OF THE LIEBER CODE HEA,DQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY JULY 1963 PREFACE The Milita.ry Law Review is designed to provide a medium for those interested in the field of military law to share the product of their experience and research with their fellow lawyers. Articles should be of direct concern and import in this area of scholarship, and preference will be given to those articles having lasting value as reference material for the military lawyer. The Jli7itm~Law Review does not purport tg promulgate Depart- ment of the Army policy or to be in any sense directory. The opinions reflected in each article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Judge Advocate General or the Department of the Army. Articles, comments, and notes should be submitted in duplicate, triple spnced, to the Editor, MiZitary Law Review. The Judge Advo- cate General’s School, US. Army, Charlottewille, Virginia. Foot- notes should be triple spaced, set out on pages separate from the text and follow the manner of citation in the Harvard Blue Rook. -

Inhaltsübersicht

Inhaltsübersicht Erstes Buch. Das Interregnum der langen Tagsatzung 1813—1815. S. 1-402 I. Der Durchzug der Verbündeten 1813/1814 S. 3— 62 Lage im Beginn des Jahres 1813. Verschärfung der Zen sur und Kontinentalsperre 3. — Erhöhung des Rekrutentributs an Napoleon 4. — Mülinens Projekt einer Bewaffnung 5. — Ordentliche Tagsatzung in Zürich 6. — Außerordentliches Trup- , penbegehren Napoleons 7. — Landammann Reinhard 8. — Räumung des Tessin 9. — Außerordentliche Tagsatzung 10. — Verhinderung eines größeren Truppenaufgebots durch Napo- leon. Neutralitätserklärung 11. — Anerkennung der Neutralität durch Napoleon 12. — Kriegsplan der Verbündeten. Capo d'Jstria und Lebzeltern in Zürich 13. — Motive der schweiz. Neutralität 14. — Reaktionshoffnungen in Bern 15. — Besorg nisse der Demokraten 16. — Unzulänglichkeit der Grenzbesetzung 17. Unentschlossenheit Reinhards 18. — Vorrücken der Haupt armee gegen die Schweiz 19. — Befehle Schwarzenbergs für den Rheinübergang 21. — Kaiser Alexander, Laharpe, Jomini, Fräulein Mazelet21/22. — Reding und Escher in Frankfurt 22/23. — Anscheinende Anerkennung der Neutralität, Sistierung des Ein- Marsches 23. — Metternich, Schwarzenberg, Radetzky gegen die Neutralität 24. — Verbot der Neutralitätsproklamation durch die ->Berner Regierung. Sendung Zeerleders und Mills 26. — Lan desverrat der Berner Unbedingten 27. — Graf Johann von Salis-Soglio 28. — Das Waldshuter Komitee in Freiburg 29. — Entschluß des Kaisers Franz zum Einmarsch 31. — Metternich und die Schweizer Gesandten 32i — Kapitulation von Lörrach ' 33. — Rückzug der eidg. Armee 34. — Auflösung der eidg. Ar- mee 35. — Rheinübergang der Österreicher. Bubna in Bern 36. — Die Österreicher in Neuenburg und Biel 37. — In Schaff- .Hausen und Zürich 38. — Vormarsch der Hauptarmee nach Frankreich 39. — Bubna in Lausanne 40. — Genf unter fran zösischer Herrschaft 41. — Gärung in Genf 42. — Bubna in Genf. e Provisorische Regierung 44.