On the Way to Becoming a Federal State (1815-1848)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canton of Vaud: a Drone Industry Booster

Credit photo: senseFly Canton of Vaud: a drone industry booster “We now Engineering Quality, Trusted Applications & Neutral Services practically cover Switzerland offers a unique multicultural and multidisciplinary drone ecosystem ideally the entire located in the centre of Europe. Swiss drone stakeholders have the expertise and spectrum of experience that can be leveraged by those looking to invest in a high growth industry, technology for develop their own business or hire talent of this new era for aviation. Foreign small drones: companies, like Parrot and GoPro, have already started to invest in Switzerland. sensors and control, Team of teams mechatronics, Swiss academia, government agencies, established companies, startups and industry mechanical associations have a proven track record of collaborating in the field of flying robotics design, and unmanned systems. Case in point: the mapping solution proposed by senseFly communication, (hardware) and Pix4D (software). Both are EPFL spin-offs, respectively from the and human Intelligent Systems Lab & and the Computer Vision Labs. They offer a good example of interaction.” how proximity to universities and the Swiss aviation regulator (FOCA) gave them a competitive and market entry advantage. Within three years the two companies have Prof. Dario Floreano, collectively created 200 jobs in the region and sell their products and services Director, Swiss worldwide. Another EPFL spin-off, Flyability, was able to leverage know-how of National Centre of regionally strong, robust and lightweight structure specialists, Décision and North TPT Competence and to produce their collision tolerant drone that won The UAE Drones for Good Award of Research Robotics USD One Million in 2015. -

Guide to the Canton of Lucerne

Languages: Albanian, Arabic, Bosnian / Serbian / Croatian, English, French, German, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, Spanish, Tamil, Tigrinya Sprache: Englisch Acknowledgements Edition: 2019 Publisher: Kanton Luzern Dienststelle Soziales und Gesellschaft Design: Rosenstar GmbH Copies printed: 1,800 Available from Guide to the Canton of Lucerne. Health – Social Services – Workplace: Dienststelle Soziales und Gesellschaft (DISG) Rösslimattstrasse 37 Postfach 3439 6002 Luzern 041 228 68 78 [email protected] www.disg.lu.ch › Publikationen Health Guide to Switzerland: www.migesplus.ch › Health information BBL, Vertrieb Bundes- publikationen 3003 Bern www.bundespublikationen. admin.ch Gesundheits- und Sozialdepartement Guide to the Canton of Lucerne Health Social Services Workplace Dienststelle Soziales und Gesellschaft disg.lu.ch Welcome to the Canton Advisory services of Lucerne An advisory service provides counsel- The «Guide to the Canton of Lucerne. ling from an expert; using such a Health – Social Services – Workplace» service is completely voluntary. These gives you information about cantonal services provide information and and regional services, health and support if you have questions that need social services, as well as information answers, problems to solve or obliga- on topics related to work and social tions to fulfil. security. For detailed information, please consult the relevant websites. If you require assistance or advice, please contact the appropriate agency directly. Some of the services described in this guide may have changed since publication. The guide does not claim to be complete. Further information about health services provided throughout Switzerland can be found in the «Health Guide to Switzerland». The «Guide to the Canton of Lucerne. Health – Social Services – Work- place» is closely linked to the «Health Guide to Switzerland» and you may find it helpful to cross-reference both guides. -

Selected Information

Selected information SNB 120 Selected information 2002 1 Supervisory and executive bodies (as of 1 January 2003) Hansueli Raggenbass, Kesswil, National Councillor, Attorney-at-law, President Bank Council Philippe Pidoux, Lausanne, Attorney-at-law, Vice President (Term of office 1999–2003) Kurt Amsler, Neuhausen am Rheinfall, President of the Verband Schweizerischer Kantonalbanken (association of Swiss cantonal banks) The members elected by Käthi Bangerter, Aarberg, National Councillor, Chairwoman of the Board of Bangerter- the Annual General Meeting of Shareholders are marked Microtechnik AG with an asterisk (*). * Fritz Blaser, Reinach, Chairman of Schweizerischer Arbeitgeberverband (Swiss employers’ association) Pierre Darier, Cologny, partner of Lombard Odier Darier Hentsch & Cie, Banquiers Privés * Hugo Fasel, St Ursen, National Councillor, Chairman of Travail.Suisse Laurent Favarger, Develier, Director of Four électrique Delémont SA Ueli Forster, St Gallen, Chairman of the Swiss Business Federation (economiesuisse), Chairman of the Board of Forster Rohner Ltd * Hansjörg Frei, Mönchaltorf, Chairman of the Swiss Insurance Association (SIA), member of the extended Executive Board of Credit Suisse Financial Services * Brigitta M. Gadient, Chur, National Councillor, partner in a consulting firm for legal, organisational and strategy issues Serge Gaillard, Bolligen, Executive Secretary of the Swiss federation of trade unions Peter Galliker, Altishofen, entrepreneur, President of the Luzerner Kantonalbank Marion Gétaz, Cully, Member of the -

Advisory Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities

Strasbourg, 2 September 2008 GVT/COM/II(2008)003 ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES COMMENTS OF THE GOVERNMENT OF SWITZERLAND ON THE SECOND OPINION OF THE ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES BY SWITZERLAND (received on 28 August 2008) GVT/COM/II(2008)003 INTRODUCTORY REMARKS The Advisory Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities adopted its second opinion on Switzerland at its 31st meeting on 29 February 2008. The opinion was transmitted to the Permanent Representative of Switzerland to the Council of Europe on 25 April 2008. Switzerland was then invited to submit its comments up to 25 August 2008. Switzerland is pleased that the Advisory Committee’s delegation, on its official visit to the country from 19 to 21 November 2007, was able to meet numerous representatives of the Federal administration, the cantonal authorities, the minorities themselves and NGOs. It welcomes the fact that during the visit the Advisory Committee was able to obtain, to its satisfaction, all the information needed to assess the situation of the national minorities in the country. In that regard, Switzerland wishes to stress the importance it attaches to the constructive dialogue which has grown up between the Advisory Committee and the Swiss authorities. Switzerland received with great interest the Advisory Committee’s second opinion on Switzerland. The detailed and perceptive findings of the Advisory Committee bear witness to its conscientious scrutiny of the situation of the minorities in Switzerland and its attention to the important issues and difficulties. -

Canton of Basel-Stadt

Canton of Basel-Stadt Welcome. VARIED CITY OF THE ARTS Basel’s innumerable historical buildings form a picturesque setting for its vibrant cultural scene, which is surprisingly rich for THRIVING BUSINESS LOCATION CENTRE OF EUROPE, TRINATIONAL such a small canton: around 40 museums, AND COSMOPOLITAN some of them world-renowned, such as the Basel is Switzerland’s most dynamic busi- Fondation Beyeler and the Kunstmuseum ness centre. The city built its success on There is a point in Basel, in the Swiss Rhine Basel, the Theater Basel, where opera, the global achievements of its pharmaceut- Ports, where the borders of Switzerland, drama and ballet are performed, as well as ical and chemical companies. Roche, No- France and Germany meet. Basel works 25 smaller theatres, a musical stage, and vartis, Syngenta, Lonza Group, Clariant and closely together with its neighbours Ger- countless galleries and cinemas. The city others have raised Basel’s profile around many and France in the fields of educa- ranks with the European elite in the field of the world. Thanks to the extensive logis- tion, culture, transport and the environment. fine arts, and hosts the world’s leading con- tics know-how that has been established Residents of Basel enjoy the superb recre- temporary art fair, Art Basel. In addition to over the centuries, a number of leading in- ational opportunities in French Alsace as its prominent classical orchestras and over ternational logistics service providers are well as in Germany’s Black Forest. And the 1000 concerts per year, numerous high- also based here. Basel is a successful ex- trinational EuroAirport Basel-Mulhouse- profile events make Basel a veritable city hibition and congress city, profiting from an Freiburg is a key transport hub, linking the of the arts. -

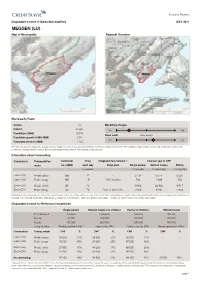

MEGGEN (LU) Map of Municipality Regional Overview

Economic Research Disposable Income in Swiss Municipalities MAY 2011 MEGGEN (LU) Map of Municipality Regional Overview Municipality Facts Canton LU Mandatory charges District Luzern low high Population (2009) 6'515 Fixed costs Swiss average Population growth (1999-2009) 1.0% low high Employed persons (2008) 1'729 The fixed costs comprise: living costs, ancillary expenses, charges for water, sewers and waste collection, cost of commuting to nearest center. The mandatory charges comprise: Income and wealth taxes, social security contributions, mandatory health insurance. Both are standardized figures taking the Swiss average as their zero point. Information about Commuting Commute to Transportation Commuter Time Integrated fare network / Cost per year in CHF mode no. (2000) each way travel pass Single person Married couple Family in minutes 1 commuter 2 commuters 1 commuter Luzern (LU) Private vehicle 965 8 - 2'134 6'174 2'207 Luzern (LU) Public transp. 965 18 TVLU 2 Zones 594 1'188 594 Zürich (ZH) Private vehicle 80 42 - 9'506 22'362 9'917 Zürich (ZH) Public transp. 80 72 Point-to-point ticket 2'628 5'256 2'628 Information on commuting relates to routes to the nearest relevant center. The starting point in each case is the center of the corresponding municipality. Travel costs associated with vehicles vary according to household type and are based on the following vehicle types: Single person = compact car, married couple = higher-price-bracket station wagon + compact car, family: medium-price-bracket station wagon. Disposable Income for Reference Households Single person Married couple (no children) Family (2 children) Retired couple In employment 1 person 2 persons 1 person Retired Income 75'000 250'000 150'000 80'000 Assets 50'000 600'000 300'000 300'000 Living situation Rented apartment 60m2 High-quality SFH Medium-quality SFH Rented apartment 100m2 Commute to Transp. -

Clarity on Swiss Taxes 2019

Clarity on Swiss Taxes Playing to natural strengths 4 16 Corporate taxation Individual taxation Clarity on Swiss Taxes EDITORIAL Welcome Switzerland remains competitive on the global tax stage according to KPMG’s “Swiss Tax Report 2019”. This annual study analyzes corporate and individual tax rates in Switzerland and internationally, analyzing data to draw comparisons between locations. After a long and drawn-out reform process, the Swiss Federal Act on Tax Reform and AHV Financing (TRAF) is reaching the final stages of maturity. Some cantons have already responded by adjusting their corporate tax rates, and others are sure to follow in 2019 and 2020. These steps towards lower tax rates confirm that the Swiss cantons are committed to competitive taxation. This will be welcomed by companies as they seek stability amid the turbulence of global protectionist trends, like tariffs, Brexit and digital service tax. It’s not just in Switzerland that tax laws are being revised. The national reforms of recent years are part of a global shift towards international harmonization but also increased legislation. For tax departments, these regulatory developments mean increased pressure. Their challenge is to safeguard compliance, while also managing the risk of double or over-taxation. In our fast-paced world, data-driven technology and digital enablers will play an increasingly important role in achieving these aims. Peter Uebelhart Head of Tax & Legal, KPMG Switzerland Going forward, it’s important that Switzerland continues to play to its natural strengths to remain an attractive business location and global trading partner. That means creating certainty by finalizing the corporate tax reform, building further on its network of FTAs, delivering its “open for business” message and pressing ahead with the Digital Switzerland strategy. -

Swiss Single Market Law and Its Enforcement

Swiss Single Market Law and its Enforcement PRESENTATION @ EU DELEGATION FOR SWITZERLAND NICOLAS DIEBOLD PROFESSOR OF ECONOMIC LAW 28 FEBRUARY 2017 overview 4 enforcement by ComCo 3 single market act . administrative federalism . principle of origin . monopolies 2 swiss federalism 1 historical background 28 February 2017 Swiss Single Market Law and its Enforcement Prof. Nicolas Diebold 2 historical background EEA «No» in December 1992 strengthening the securing market competitiveness of access the swiss economy 28 February 2017 Swiss Single Market Law and its Enforcement Prof. Nicolas Diebold 3 historical background market access competitiveness «renewal of swiss market economy» § Bilateral Agreements I+II § Act on Cartels § Autonomous Adaptation § Swiss Single Market Act § Act on TBT § Public Procurement Acts 28 February 2017 Swiss Single Market Law and its Enforcement Prof. Nicolas Diebold 4 swiss federalism 26 cantons 2’294 communities By Tschubby - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12421401 https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/3e/Schweizer_Gemeinden.gif 28 February 2017 Swiss Single Market Law and its Enforcement Prof. Nicolas Diebold 5 swiss federalism – regulatory levels products insurance banking medical services energy mountaineering legal services https://pixabay.com/de/schweiz-alpen-karte-flagge-kontur-1500642/ chimney sweeping nursing notary construction security childcare funeral gastronomy handcraft taxi sanitation 28 February 2017 Swiss Single Market Law and its Enforcement Prof. Nicolas Diebold 6 swiss federalism – trade obstacles cantonal monopolies cantonal regulations procedures & fees economic use of public domain «administrative federalism» public public services procurement subsidies 28 February 2017 Swiss Single Market Law and its Enforcement Prof. -

PARLIAMENT of CANTON VAUD LAUSANNE, SWITZERLAND a BONELL I GIL + ATELIER CUBE ARCHITECTS 1 /4

PARLIAMENT OF CANTON VAUD LAUSANNE, SWITZERLAND A BONELL i GIL + ATELIER CUBE ARCHITECTS 1 /4 Site plan Befor the fire Fire 2002 The Parliament of Lausanne, originally built by Alexandre Perregaux in 1803 rebuilt by Viollet-le-Duc in the 1800s) and the The façade of Rue Cité-Devant, a grand opening that acts as the new on the occasion of the foundation of the Canton of Vaud, was destroyed by Saint-Maire Castle (built in the fourteenth cen- access to the building. Crossing the threshold means entering into a parti- a fire in 2002. tury) provides a setting that rebalances the cular atmosphere, a space that fuses the past and the present. presence of the religious and military institu- Its reconstruction presented the opportunity to reassess the criteria that tions. The reconstruction of the Salle Perregaux, with its neoclassical façade saved would allow to solve both the parliamentary seat and the revitalization of the from the fire, is another of the attractions of the project. The old entrance to neighbouring buildings. In closer view, the project presents itself as a unitary ensemble, formally the Parliament is now used as a Salle des pas perdus, a hall for gatherings. autonomous, containing all part of the programme and where the Great As- The project proposed an architecture capable of restoring the continuity and sembly Hall assumes its prominent role both spatially and functionally. The new Parliament headquarters has been erected on top of historical ves- atmosphere of the historical city. An architecture that would be the synthesis tiges and wants to present itself as an efficient and modern building, cons- between old and new, between traditional construction and new technolo- The three-storey high foyer unites and separates the diverse spaces, but it tructed using innovative techniques but offering an image of timelessness. -

Switzerland 4Th Periodical Report

Strasbourg, 15 December 2009 MIN-LANG/PR (2010) 1 EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES Fourth Periodical Report presented to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in accordance with Article 15 of the Charter SWITZERLAND Periodical report relating to the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages Fourth report by Switzerland 4 December 2009 SUMMARY OF THE REPORT Switzerland ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (Charter) in 1997. The Charter came into force on 1 April 1998. Article 15 of the Charter requires states to present a report to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe on the policy and measures adopted by them to implement its provisions. Switzerland‘s first report was submitted to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in September 1999. Since then, Switzerland has submitted reports at three-yearly intervals (December 2002 and May 2006) on developments in the implementation of the Charter, with explanations relating to changes in the language situation in the country, new legal instruments and implementation of the recommendations of the Committee of Ministers and the Council of Europe committee of experts. This document is the fourth periodical report by Switzerland. The report is divided into a preliminary section and three main parts. The preliminary section presents the historical, economic, legal, political and demographic context as it affects the language situation in Switzerland. The main changes since the third report include the enactment of the federal law on national languages and understanding between linguistic communities (Languages Law) (FF 2007 6557) and the new model for teaching the national languages at school (—HarmoS“ intercantonal agreement). -

Switzerland1

YEARBOOK OF INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW - VOLUME 14, 2011 CORRESPONDENTS’ REPORTS SWITZERLAND1 Contents Multilateral Initiatives — Foreign Policy Priorities .................................................................. 1 Multilateral Initiatives — Human Security ................................................................................ 1 Multilateral Initiatives — Disarmament and Non-Proliferation ................................................ 2 Multilateral Initiatives — International Humanitarian Law ...................................................... 4 Multilateral Initiatives — Peace Support Operations ................................................................ 5 Multilateral Initiatives — International Criminal Law .............................................................. 6 Legislation — Implementation of the Rome Statute ................................................................. 6 Cases — International Crimes Trials (War Crimes, Crimes against Humanity, Genocide) .... 12 Cases — Extradition of Alleged War Criminal ....................................................................... 13 Multilateral Initiatives — Foreign Policy Priorities Swiss Federal Council, Foreign Policy Report (2011) <http://www.eda.admin.ch/eda/en/home/doc/publi/ppol.html> Pursuant to the 2011 Foreign Policy Report, one of Switzerland’s objectives at institutional level in 2011 was the improvement of the working methods of the UN Security Council (SC). As a member of the UN ‘Small 5’ group, on 28 March 2012, the Swiss -

Page 1 of 7 Core Group Wolf Background Information Member State: Switzerland Location: Canton of Bern Large Carnivores: Wolf

Core Group Wolf Background Information Member state: Switzerland Location: Canton of Bern Large carnivores: Wolf Population of large carnivores in the area: After the extermination of wolves in the 19th century, the first wolf returned in 2006 to the Canton of Bern.1 Since then only single wolves passed through the Canton of Bern until in 2016 the first pair of wolves established in the Canton of Bern and Fribourg. Offspring was expected this year. However, the female wolf was found dead on 9 June in the canton of Fribourg. She had been poisoned. There are no signs of the male wolf anymore for the past few months, neither.2 Currently, there are indications of several single wolves in the Canton of Bern. Main conflicts (including e.g. frequency of depredation events etc.): Depredation of livestock, particularly sheep is the main cause of conflict. Although farmers are satisfied with the compensation paid, they are emotionally affected and have more labour if they agree to implement livestock protection measures. As the economy of the Canton of Bern depends heavily on tourism and outdoor activities in the picturesque Alps with their grazing herds of livestock, a concerned part of society fears that a growing population of wolves will put this at risk. There have been incidences of livestock guarding dogs attacking dogs of hikers and frightening hikers. Main conservation issues: Illegal killing of wolves has happened before and it is still a major problem. With the establishment of a new wolf pack, the canton faces new challenges. Low acceptance of wolf by part of the society combined with symbolic and wider social-economic issues also play a major role.