Relationships, Community, and Housing Preferences in Linden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parks and Recreation Master Plan

2017-2021 FEBRUARY 28, 2017 Parks and Recreation Master Plan 2017-2021 Parks and Recreation Master Plan City of Southfi eld, Michigan Prepared by: McKenna Associates Community Planning and Design 235 East Main Street, Suite 105 Northville, Michigan 48167 tel: (248) 596-0920 fax: (248) 596-.0930 www.mcka.com ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The mission of the Southfi eld Parks and Recreation Department is to provide excellence and equal opportunity in leisure, cultural and recreational services to all of the residents of Southfi eld. Our purpose is to provide safe, educationally enriching, convenient leisure opportunities, utilizing public open space and quality leisure facilities to enhance the quality of life for Southfi eld’s total population. Administration Staff Parks and Recreation Board Terry Fields — Director, Parks & Recreation Department Rosemerry Allen Doug Block — Manager, P&R Administration Monica Fischman Stephanie Kaiser — Marketing Analyst Brandon Gray Michael A. Manion — Community Relations Director Jeannine Reese Taneisha Springer — Customer Service Ronald Roberts Amani Johnson – Student Representative Facility Supervisors Planning Department Pattie Dearie — Facility Supervisor, Beech Woods Recreation Center Terry Croad, AICP, ASLA — Director of Planning Nicole Messina — Senior Adult Facility Coordinator Jeff Spence — Assistant City Planner Jonathon Rahn — Facility Supervisor, Southfi eld Pavilion, Sarah K. Mulally, AICP — Assistant City Planner P&R Building and Burgh Park Noreen Kozlowski — Landscape Design Coordinator Golf Planning Commission Terri Anthony-Ryan — Head PGA Professional Donald Culpepper – Chairman Dan Bostick — Head Groundskeeper Steven Huntington – Vice Chairman Kathy Haag — League Information Robert Willis – Secretary Dr. LaTina Denson Parks/Park Services Staff Jeremy Griffi s Kost Kapchonick — Park Services, Park Operations Carol Peoples-Foster Linnie Taylor Parks Staff Dennis Carroll Elected Offi cials & City Administration Joel Chapman The Honorable Kenson J. -

Child Care Access in 2020

Summer 2019 CHILD CARE ACCESS IN 2020: How will pending state mandates affect availability in Franklin County, Ohio? Abel J. Koury, Ph.D., Jamie O’Leary, MPA, Laura Justice, Ph.D., Jessica A.R. Logan, Ph.D., James Uanhoro INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE Child care provision is a critical service for children and their families, and it can also bolster the workforce and larger economy. For child care to truly be beneficial, however, it must be affordable, accessible, and high quality. A current state requirement regarding child care programming may have enormous implications for many of Ohio’s most vulnerable families who rely on funding for child care. Specifically, by 2020, any Ohio child care provider that accepts Publicly Funded Child Care (PFCC) subsidies must both apply to and receive entry into Ohio’s quality rating and improvement system – Step Up To Quality (SUTQ) (the “2020 mandate”). The purpose of this paper is two-fold. First, we aim to provide an in-depth examination of the availability of child care in Franklin County, Ohio, with a specific focus on PFCC-accepting programs, and explore how this landscape may change in July of 2020. Second, we aim to examine the locations of programs that are most at risk for losing child care sites, highlighting possible deserts through the use of mapping. Crane Center for Early Childhood Research and Policy Improving children’s well-being through research, practice, and policy.1 2020 SUTQ Mandate: What is at stake? According to an analysis completed by Franklin County Jobs and Family Services (JFS), if the 2020 mandate went into effect today, over 21,000 young children would lose their care (Franklin County Jobs and Family Services, 2019). -

Fire Alarm Package 4A – North Linden Elementary School, Beechcroft High School & Columbus Alternative High School

Columbus City Schools Operation: Fix It – Fire Alarm Package 4A – North Linden Elementary School, Beechcroft High School & Columbus Alternative High School LEGAL NOTICE: Operation: Fix It – Fire Alarm Package 4A – North Linden Elementary School, Beechcroft High School & Columbus Alternative HS Sealed bids will be received by the BOARD OF EDUCATION, City School District of Columbus, Ohio, Office of Capital Improvements, 889 E. 17th Ave, Columbus OH 43211 until Friday, April 26, 2019, at 10:00 AM and will be opened and read publicly immediately thereafter for the Operation: Fix It – Fire Alarm Package 4A Upgrades for North Linden Elementary School, Beechcroft High School and Columbus Alternative High School according to the plans and specifications, dated March 29, 2019, prepared by Osborn Engineering. The total estimated cost for materials and labor for North Linden Elementary School Fire Alarm Upgrades – Fire Alarm Contractor is $103,784.00. The total estimated cost for materials and labor for Beechcroft High School Fire Alarm Upgrades – Fire Alarm Contractor is $244,069.00. The total estimated cost for materials and labor for Columbus Alternative High School Fire Alarm Upgrades – Fire Alarm Contractor is $205,096.00. Plans and Specifications may be secured at the bidder’s expense plus shipping costs from Franklin Imaging, 500 Schrock Rd, Columbus, OH 43229, (T) 614-885-6894 or [email protected]. Public inspection may be made at the McGraw Hill Construction Dodge / Builders Exchange of Central Ohio Plan Room, 1175 Dublin Road, Columbus, Ohio 43215; The Builders Exchange, 9555 Rockside Road, Suite 300, Valley View, OH 44125; the Central Ohio Minority Business Assistance Center, 1393 East Broad Street, Columbus, OH 43203; the Minority & Independent Contractors Alliance, 1452 East Livingston Avenue, Columbus, Ohio 43205 and the Ohio Business Development Center, 1612 Old Leonard Avenue, Columbus, Ohio 43219. -

Identifying Barriers to Linden Energy Saving Programs

Identifying Barriers to Linden Energy Saving Programs Project Report AEDECON 4567: Assessing Sustainability In Response to: City of Columbus RFP Solicitation Number EEDS009 Stephanie Mitchell, Pat Cullinan, Jessie Gibson, Matthew Griffin, Morgan Williams Identifying Barriers to Linden Energy Saving Programs 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 Key Action Items .................................................................................................................... 5 Study Area ................................................................................................................................. 6 Figure 1: Residential Energy Burden ...................................................................................... 6 Data Collection........................................................................................................................... 7 Figure 2: Social Network Map ................................................................................................. 8 Image 1: CES Kickoff Event ................................................................................................... 9 Image 2: CES Kickoff Event ..................................................................................................10 Research Findings ....................................................................................................................10 -

LINDEN of Babies in Our Community

Where we live, learn, work and play has an impact on our health and the health LINDEN of babies in our community. CelebrateOne works with INFANT community leaders and residents in eight high-priority MORTALITY neighborhoods to make them safer and healthier PROFILE for moms-to-be, babies, and families. This affects life expectancy 1,2 INFANT LIFE EXPECTANCY 1 MORTALITY Linden Franklin County Infant mortality is the death of a child before they turn one year of age. In 65.2 77.7 Central Ohio, black babies die at a rate 2.5 Age In years times that of white babies. Linden Franklin County 24 781 CAUSES OF # of infant deaths from 2011-2015 INFANT MORTALITY Linden Franklin County • Born too small and too soon • Birth defects • Unsafe sleep 20.2 8.4 • Smoking Infant deaths per 1,000 live births • Neighborhood health 1 Linden Franklin County UNSAFE SLEEP 16.7% Once a baby is 1 month old, the 4 110 biggest risk for infant mortality # of sleep-related infant deaths from is sleep-related death. All 2011-2015 babies should sleep alone, One in six (16.7%) infant deaths in the Linden area were on their back, and in an due to unsafe sleep, compared to approximately one in empty crib. seven (14.1%) in Franklin County overall. 1 Linden Franklin County LOW BIRTH WEIGHT The leading cause of infant death is babies being 16.3 9.1 born too early and too small to survive. % of births low birth weight (< 5.5 lbs) To learn more about CelebrateOne and provide input on our neighborhood development and community building plan.. -

Community Reinvestment Areas

Godown Morse Community Reinvestment Areas n Davidso Henderson HOUSING DIVISION Ferris Cooke Easton Way Cooke M C o he r r Cooke s ry e B Maize C o ro t Karl t ss o in m Reed g Mccoy CRA STATUS Riverside Innis Market Ready Westerville Cemetery O l e Indianola n Mccutcheon Dublin t Oakland Park Ready for Revitalization a North Broadway Fishinger n g Stygler n ow y st n R h i o v Agler 270 J Ready for Opportunity e r Weber Mcguey Cleveland Tremont High Agler Ackerman Mill Granville CRA INFORMATION Dodridge 62 The designations approved by City Council are listed below. Hudson Northwest Mock Stelzer Sunbury . AC Humko Berrell Johnstown 33 Lane 71 . Fifth By Northwest Cassady . Franklinton Joyce Roberts 315 . Hilltop 17th Holt International G . Linden Fourth at eway Kinnear . Livingston and James Kenny Summit t 11th r o . Milo-Grogan p ir A King . Near East Trabue Brentnell 5th . North Central . Short North 3rd 5th Dublin Neil Starr . Southside 2nd Nelson . Weinland Park Wilson Leonard Grandview 670 St Clair Goodale Goodale Mt Vernon s 16 r e v i Taylor Fisher R Hamilton n Nationwide Naughten Twi Broad Spring Long M Grant a r Governor Valleyview McKinley c Phillipi o n i Third Souder Bryden Hartford 40 Town Rich Yearling Central Main Front James Town Rich Davis Glenwood 0 0.5 1 2 Miles 70 Cole Hague Ohio Coordinate System: State Plane Ohio South; U.S. Foot; North American Datum Miller Sullivant Kelton Livingston College Date: .. Mound Whittier Edited: .. Greenlawn Thurman Created by: Lockbourne Eakin Fairwood Columbus Planning Division/mc Stimmel W. -

Milo Grogan Sustainability Plan.Pdf

Milo-Grogan Sustainability Plan A Product of City and Regional Planning Program The Ohio State University Spring 2015 Acknowledgements We acknowledge and extend sincere appreciation to everyone who assisted us in our research endeavors during the term. We would like to Student Team Members: extend particular thanks to: Robert Barksdale (MGAC), Todd Pulsifer James Burdin and Grant Pittmann (Department of Public Utilities), Erin Miller (Office Brian Kinninger of Environmental Stewardship), Shoreh Elhami (City of Columbus), Andrew Crozier Kevin Wheeler, Christine Leed and Mark Dravillas (Planning Division), George Larger Michael Kasler (Office of Sustainability), Ben Piscitelli (Franklin County Shelley Denison Board of Elections), Joanne Pearsol (Center for Public Health Practice), Kelsey Mailman Jason Mulhausen and Matthew Dickinson (Third Hand Bicycle Cooper- Timothy Dietrich ative), Laura Hess (Chamber of Commerce), Belinda Taylor and Andy Luan Nguyen Volenik (Central Ohio Transit Authority), Tasha Williams (Boys & Girls Ran Duan Club of Columbus), Doreen Gosha (Martin Janis Senior Community Richard Rush Center), Craig Nettles (J.H. Ross Family Life & Community Center), Richard Edwards Brittany Ylissari (Habitat for Humanity), Christy Rogers (The Kirwan Chia-Chin Yu Institute), Scotte Elliott and Tammy Robertson (MORPC), Kevin Ei- David Zeller gle (Ecohouse Solar), Mark Bellamy (Public Utilities Commission of Ohio), Cynthia Rickman (Department of Development), Shannon Pine Instructor: Dr. Maria Manta Conroy and Paul Friedman (Columbus Building and Zoning), Kraig Shrewsberry and Noel Alcala (ODOT), Rachel M. Silsdorf (Near East Area Liaison), Scott Ulrich (Public Health), Jake Boswell (OSU), and Steve Bollinger (Wagonbrenner Development). You all provided invaluable information, resources, and insight that guided our efforts throughout the planning process. -

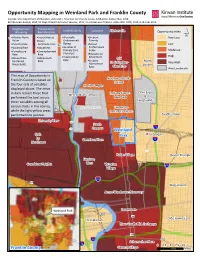

Opportunity Mapping in Weinland Park and Franklin County

Opportunity Mapping in Weinland Park and Franklin County Sources: Ohio Department of Education, 2010-2011; American Community Survey, 2006-2010; Justice Atlas, 2008; ESRI Business Analyst, 2010; US Dept of Health & Human Services, 2010; County Business Patterns, 2006-2009; COTA, 2010; HUD User, 2010 Neighborhood Transportation Health & Safety EducatioSnouth Clintonville & Housing & Employment Opportunity Index East Linden Up•pMeerd Aiarnli Hnogmtoen •Transit Access •Medically •Student Very Low Value •Mean Underserved Poverty •Poverty Rate Commute Time RiverRvaiteinwg •School Low •Number of Performance •Vacancy Rate •Job Access Moderate •Foreclosure •Unemployment Primary Care Index Providers Rate Rate •Educational High •Rate of Cost- •Job Growth •Incarceration Attainment Old Burdened Rate Rate •Student N. Columbus- North Very High Attendence Households Glen Echo Linden Rate Area Landmarks This map of Opportunity in Northwood Park- Franklin County is based on SoHud the four sets of variables North Campus displayed above. The areas in dark red are those that Indiana Forest- Ohio Expo West & Main Campus & performed the best across Iuka Park Fairgrounds these variables among all census tracts in the county, Ohio State University University- while the light yellow areas Indianola Terrace performed the poorest . South Linden University View 315 South Campus 71 315 Weinland Fifth Milo-Grogan by Park Dennison Place 71 Northwest 3 Italian Village Devon Triangle Harrison West Victorian Grandview Heights 670 Village 670 33 King-Lincoln North Franklinton -

No Vacation in Sight for Some Salary Talks Personnel, Water

THE NEW Your want ad The Zip Code is easy to place for Linden is -Phone 686-7700 which became a Suburban Publishing* Corp. newspaper on July 2, 1964 An Official Newspaper For The City of Linden 0 7 0 3 6 Published Each Thur»day by Suburban Publl*hlng Corp. VOL. 19 - NO 44 UNDEN. N.J., THURSDAY, JUNE 28, 1973 Subscription Rate $6.00 Yearly 218 North Wood ov»., Llndon, N.J. 07036 Second Clas* Postage Paid ot Linden, N.J. 20 Cents Per Copy •£* No vacation in sight for some salary talks Fact-finder report due on teachers Negotiation session slated for public works It may be vacation time for students and some workers, but contracts with public works employees and teachers and school ad ministrators are still unsettled. The most recent contract agreement came Monday night when the Board of Education approved a salary guide for school custodians at a special session in Linden High School. Still BEFORE THE FINAL BELL sounded last week, it was announced John Gregorio and Herman Mopsick, LHS principal. to be approved, however, are pacts with ad by A R. Taranto, superintendent of schools, that the State Background information was provided for the students by ministrators and cafeteria workers. The Board Board of Education awarded to F.R. Cerillo, Linden High art films and guest speakers. The speakers included Thomas may also go through another summer without a teacher, a MINI-grant to develop anti-drug posters by the Long, assistant superintendent of Linden Schools; John teachers’ contract. silk screen process. -

The Unseen Stream of Iuka Ravine and Other Stories—Part Two by Daryl Largent N 1832, the Treaty of Pontotoc Creek Was Signed

An Advocate for Community Resources Published by Friends of the Ravines (FOR) Fall 2009/Winter 2010 The Unseen Stream of Iuka Ravine And Other Stories—Part Two by Daryl Largent n 1832, the Treaty of Pontotoc Creek was signed. Among More of the Neil family, including William, would end up other things, the treaty called for the Chickasaw nation to living in the new brick house after the farmhouse burned. Icede land east of the Mississippi and obtain new land in Henry Neil, William’s youngest son, owned the brick house by the west. A Chickasaw named Chief Ish-ta-ki-yu-ka-tubbe 1872. It was Henry Neil who was the fi rst Ohioan to enlist in endorsed and helped ratify the treaty, but it is not for his the Union Army for the Civil War. diplomatic skills that he is remembered today. Instead, it is his Henry Neil soon became Captain Neil. He fought and was name or, rather, a contraction of it: Chief Iuka. among the many wounded at the Battle of Iuka before making Other than supporting the treaty and having a recognizable his way back to Columbus. Captain Neil named the brick nickname, Chief Iuka is known for suff ering a terrible illness. home Indianola (which, like Iuka, is a town in Mississippi). So severe was his sickness that he was literally carried to a Apparently fi nding his talent, he may have been responsible for spot in what is now northeastern Mississippi to drink from renaming Wachita Avenue Indianola Avenue, as marked on an supposedly curative springs. -

City of Long Beach Historic Context Statement

City of Long Beach Historic Context Statement Prepared for: City of Long Beach Department of Development Services Office of Historic Preservation 333 West Ocean Boulevard Long Beach, California 90802 Prepared by: Sapphos Environmental, Inc. 430 North Halstead Street Pasadena, California 91107 July 10, 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTIONS PAGE 1.0 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Objectives and Scope............................................................................................. 5 1.2 Working Definitions............................................................................................... 6 1.3 Report Preparation ................................................................................................. 8 1.4 Historic Context Statement Organization................................................................ 8 2.0 LOCATION...................................................................................................................... 10 3.0 STUDY METHODS.......................................................................................................... 14 3.1 Historical Research............................................................................................... 14 3.2 Previous Surveys................................................................................................... 15 3.3 Field Reconnaissance........................................................................................... -

Food Resources in Your Neighborhood

1 FREE MEAL AND FOOD ASSISTANCE PRORGAMS FOR QUESTIONS RELATED TO COVID-19, CALL COLUMBUS PUBLIC HEALTH: 614-645-1519 Or the Ohio Department of Health at 1-833-4-ASK-ODH (1-833-427-5634). FOR MORE INFORMATION RELATED TO COVID-19 PLEASE VISIT: COLUMBUS.GOV/CORONAVIRUS Disclaimer: The provider of this resource list assumes no responsibility for the accuracy of the information. This does not represent all the Pantries and Meals and resources available in the area. The data includes self-reported and third party reported information, understood to be current and complete for each site as of: October 2020. Farmer to Families Food Box Food Box Program: This is a FREE program available to NCH patients and families. Produce boxes will be available every Thursday, in October, at the Livingston Ambulatory Building. Boxes can be picked up after 9am until all boxes have been distributed. Location: Circle Drive of the Livingston Ambulatory Building: 380 Butterfly Garden’s Drive, Columbus, OH 43 215 Produce boxes will also be available every Tuesday, in October at the Linden Primary Care Center (2nd Floor). Boxes can be picked up after 930am until all boxes have been distributed. Location: Linden Primary Care Center (Parking Lot): 1390 Cleveland Ave, Columbus, OH 43211 SOUP KITCHENS Bethany Presbyterian Church Location: 206 N. Garfield, Col,OH 43203 Phone: 614-253-0077 Service Description: Provides and serves food to those in need. Eligibility: Anyone Hours: Saturdays 11:30 a.m.-1:30 p.m. Intake Process: Walk-in Documents: No documents required. Faith Lutheran Church Location: 730 Collingwood Ave Parking Lot Phone: 614-817-3131 Service Description: Free boxed dinner pick up for all community members.