Columbus, Ohio 1812-1992

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downtown Hotels and Dining Map

DOWNTOWN HOTELS AND DINING MAP DOWNTOWN HOTELS N 1 S 2 A. Moxy Columbus Short North 3 4 W. 5th Ave. E. 5th Ave. 800 N. High St. 5 E. 4th Ave. B. Graduate Columbus 6 W. 4th Ave. 7 750 N. High St. 8 9 10 14 12 11 W. 3rd Ave. Ave. Cleveland C. Le Méridien Columbus, The Joseph 13 High St. High E. 3rd Ave. 620 N. High St. 15 16 17 18 19 20 E. 2nd Ave. D. AC Hotel Columbus Downtown 21 22 W. 2nd Ave. 517 Park St. 23 24 Summit St.Summit 4th St.4th Michigan Ave. Michigan E. Hampton Inn & Suites Columbus Downtown Neil Ave. W. 1st Ave. A 501 N. High St. 25 Hubbard Ave. 28 26 27 29 F. Hilton Columbus Downtown 32 30 31 33 34 401 N. High St. 37 35 B Buttles Ave. 38 39 36 36 40 G. Hyatt Regency Columbus 42 41 Park St. Park 43 44 45 350 N. High St. Goodale Park 47 46 48 C H. Drury Inn & Suites Columbus Convention Center 50 49 670 51 Park St. Park 54 53 88 E. Nationwide Blvd. 52 1 55 56 D I. Sonesta Columbus Downtown E 57 Vine St. 58 2 4 71 33 E. Nationwide Blvd. 315 3 59 F 3rd St.3rd 4th St.4th J. Canopy by Hilton Columbus Downtown 5 1 Short North 7 6 G H Mt. Vernon Ave. Nationwide Blvd. 77 E. Nationwide Blvd. 14 Neil Ave. 8 10 Front St. Front E. Naughten St. 9 11 I J Spring St. -

Rivers & Lakes

Rivers & Lakes Theme: Water Quality and Human Impact Age: Grade 3-6 Time: 3 hours including time for lunch Funding The Abington Foundation has funded this program for the STEAM Network to include all third grade classes in the Network. This grant covers professional development, pre and post visit activities, Lakes & Rivers program at the aquarium, transportation, and a family event with the Greater Cleveland Aquarium. The Greater Cleveland Aquarium Splash Fund is the recipient and fiscal agent for this grant from The Abington Foundation. The final report is due November 2015. Professional Development A one and a half hour teacher workshop is in place for this program. It was first presented to 4 teachers at the Blue2 Institute on July 30 by Aquarium staff. We are prepared to present it again this fall to prepare teachers for this experience. Teachers were presented with lesson plans, pre and posttests, and a water quality test kits to prepare their students to the Lakes and Rivers program. Lakes & Rivers program Overview Explore the rich history of Ohio’s waterways while journeying through Lake Erie, and the Cuyahoga River. This program will explore the deep interconnection that Ohio has with its freshwater systems through time. Students will use chemical tests to determine the quality of Cuyahoga River water and learn about Ohio’s native fish, amphibians, reptiles, through hands-on activities that teach students the importance of protecting our local waters. Standards Ohio’s Learning Standards Content Statements in science, social studies and math covered in Lakes and River s are listed below. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

14 NNP5 fojf" 10 900 ft . OW8 Mo 1024-00)1 1 (J United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Short North Mulitipie Property Area.__________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts Street car Related Development 1871-1910________________________ Automotive Related Development 1911-1940 ______ C. Geographical Data___________________________________________ The Short North area is located in Columbus, Franklin County, Ohio. It is a corridor of North High Street located between Goodale Street and King Avenue. The corridor is situated between the Ohio State University Area on the North and Downtown Columbus on the South. The Near North Side National Register Historic District is situated immediately to the west and Italian Village is local historic district to the east. King Avenue has traditionally been a dividing line between the Short North and University sections of North High Street. Interstate 670 which runs parallel with and under Goodale forms a sharp divider between Downtown and the Short North. Italian Village and the Near North Side District are distinctly residential neighborhoods that adjoin this commercial corridor. LjSee continuation sheet 0. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. -

The Schulte Family in Alpine, California

THE SCHULTE FAMILY IN ALPINE, CALIFORNIA The two things that have led to my connection and fascination with Alpine are my visits with my grandmother, Marguerite (Borden) Head or “Zuella”, and the Foss family in the 1950s, and the exquisite art work of Leonard Lester (see separate articles titled The Marguerite (Borden) and Robert Head Family of Alpine” and “Leonard Lester – Artist”). Most of the information on the Schulte family presented here is from 1) conversations with my father, Claude H. Schulte; 2) my grandfather, Christopher Henry Schulte, whose personal history was typed by his daughter, Ruth in 1942; and 3) supplemented by interviews with and records kept by my Aunt Ruth Schulte, including her mother’s diary. Kenneth Claude Schulte – December 2009 Christopher Henry Schulte, who immigrated to the United States in 1889, was born in Twistringen, Germany on 21 Dec 1874 and died 1 May 1954 in Lemon Grove, San Diego Co., California. In Arkansas he was married on 28 Jul 1901 to Flora Birdie Lee, born 16 Oct. 1883, Patmos, Hempstead Co., Arkansas and died 11 Jul 1938, Alpine, San Diego Co., California. Henry and Birdie had eight children: 1. Carl Lee Schulte b. 14 Oct 1902 Arkansas 2. Lois Birdie Schulte b. 07 Jun 1904 Arkansas 3. Otto Albert Schulte b. 29 May 1908 Arkansas 4. Lucille Schulte b. 02 Aug 1910 California 5. Claude Henry (C.H.) Schulte b. 19 Aug 1912 Arkansas 6. Harold Christopher Schulte b. 21 Mar 1915 California 7. Ruth Peace Schulte b. 10 Nov 1918 California 8. William Edward Schulte b. -

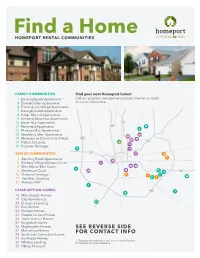

See Reverse Side for Contact Info

FAMILY COMMUNITIES Find your next Homeport home! 1 Bending Brook Apartments1 Call our property management partner (see list on back) 4 Emerald Glen Apartments for more information. 6 Framingham Village Apartments 7 Georges Creek Apartments 8 Indian Mound Apartments 9 Kimberly Meadows Apartments 10 Marsh Run Apartments 11 Parkmead Apartments 12 Pheasant Run Apartments 13 Raspberry Glen Apartments 14 Renaissance Community Village 16 15 Trabue Crossing 23 16 Victorian Heritage1 15 18 SENIOR COMMUNITIES 17 1 Bending Brook Apartments1 2 Eastway Village/Eastway Court 32 3 Elim Manor/Elim Court 5 Fieldstone Court 16 Victorian Heritage1 31 13 21 3 17 Hamilton Crossing 31 Friends VVA2 LEASE-OPTION HOMES 18 Milo Grogan Homes 19 City View Homes 20 Duxberry Landing 21 Elim Estates 22 Fairview Homes 23 Greater Linden Homes 24 Joyce Avenue Homes 25 Kingsford Homes 26 Maplegreen Homes SEE REVERSE SIDE 27 Mariemont Homes 28 South East Columbus Homes FOR CONTACT INFO 29 Southside Homes 1. Property includes both senior and family homes. 30 Whittier Landing 2. Property is in two locations. 32 Hilltop Homes II Call the number listed below for more information, including availability and current rental rates. FAMILY COMMUNITIES BR Phone Management Office Mgmt Partner 1 Bending Brook Apartments 1,2,3 614.875.8482 2584 Augustus Court, Urbancrest, OH 43123 Wallick 4 Emerald Glen Apartments 2,3,4 614.851.1225 930 Regentshire Drive, Columbus, OH 43228 CPO 6 Framingham Village Apartments 3 614.337.1440 3333 Deserette Lane, Columbus, OH 43224 Wallick 7 Georges Creek -

Northland I Area Plan

NORTHLAND I AREA PLAN COLUMBUS PLANNING DIVISION ADOPTED: This document supersedes prior planning guidance for the area, including the 2001 Northland Plan-Volume I and the 1992 Northland Development Standards. (The Northland Development Standards will still be applicable to the Northland II planning area until the time that plan is updated.) Cover Photo: The Alum Creek Trail crosses Alum Creek at Strawberry Farms Park. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Columbus City Council Northland Community Council Development Committee Andrew J. Ginther, President Albany Park Homeowners Association Rolling Ridge Sub Homeowners Association Herceal F. Craig Lynn Thurman Rick Cashman Zachary M. Klein Blendon Chase Condominium Association Salem Civic Association A. Troy Miller Allen Wiant Brandon Boos Michelle M. Mills Eileen Y. Paley Blendon Woods Civic Association Sharon Woods Civic Association Priscilla R. Tyson Jeanne Barrett Barb Shepard Development Commission Brandywine Meadows Civic Association Strawberry Farms Civic Association Josh Hewitt Theresa Van Davis Michael J. Fitzpatrick, Chair John A. Ingwersen, Vice Chair Cooperwoods Condominium Association Tanager Woods Civic Association Marty Anderson Alicia Ward Robert Smith Maria Manta Conroy Forest Park Civic Association Village at Preston Woods Condo Association John A. Cooley Dave Paul John Ludwig Kay Onwukwe Stefanie Coe Friendship Village Residents Association Westerville Woods Civic Association Don Brown Gerry O’Neil Department of Development Karmel Woodward Park Civic Association Woodstream East Civic Association Steve Schoeny, Director William Logan Dan Pearse Nichole Brandon, Deputy Director Bill Webster, Deputy Director Maize/Morse Tri-Area Civic Association Advisory Member Christine Ryan Mark Bell Planning Division Minerva Park Advisory Member Vince Papsidero, AICP, Administrator (Mayor) Lynn Eisentrout Bob Thurman Kevin Wheeler, Assistant Administrator Mark Dravillas, AICP, Neighborhood Planning Manager Northland Alliance Inc. -

Parks and Recreation Master Plan

2017-2021 FEBRUARY 28, 2017 Parks and Recreation Master Plan 2017-2021 Parks and Recreation Master Plan City of Southfi eld, Michigan Prepared by: McKenna Associates Community Planning and Design 235 East Main Street, Suite 105 Northville, Michigan 48167 tel: (248) 596-0920 fax: (248) 596-.0930 www.mcka.com ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The mission of the Southfi eld Parks and Recreation Department is to provide excellence and equal opportunity in leisure, cultural and recreational services to all of the residents of Southfi eld. Our purpose is to provide safe, educationally enriching, convenient leisure opportunities, utilizing public open space and quality leisure facilities to enhance the quality of life for Southfi eld’s total population. Administration Staff Parks and Recreation Board Terry Fields — Director, Parks & Recreation Department Rosemerry Allen Doug Block — Manager, P&R Administration Monica Fischman Stephanie Kaiser — Marketing Analyst Brandon Gray Michael A. Manion — Community Relations Director Jeannine Reese Taneisha Springer — Customer Service Ronald Roberts Amani Johnson – Student Representative Facility Supervisors Planning Department Pattie Dearie — Facility Supervisor, Beech Woods Recreation Center Terry Croad, AICP, ASLA — Director of Planning Nicole Messina — Senior Adult Facility Coordinator Jeff Spence — Assistant City Planner Jonathon Rahn — Facility Supervisor, Southfi eld Pavilion, Sarah K. Mulally, AICP — Assistant City Planner P&R Building and Burgh Park Noreen Kozlowski — Landscape Design Coordinator Golf Planning Commission Terri Anthony-Ryan — Head PGA Professional Donald Culpepper – Chairman Dan Bostick — Head Groundskeeper Steven Huntington – Vice Chairman Kathy Haag — League Information Robert Willis – Secretary Dr. LaTina Denson Parks/Park Services Staff Jeremy Griffi s Kost Kapchonick — Park Services, Park Operations Carol Peoples-Foster Linnie Taylor Parks Staff Dennis Carroll Elected Offi cials & City Administration Joel Chapman The Honorable Kenson J. -

Viewing an Exhibition

Winter 1983 Annual Report 1983 Annual Report 1983 Report of the President Much important material has been added to our library and the many patrons who come to use our collections have grown to the point where space has become John Diehl quite critical. However, collecting, preserving and dissemi- President nating Cincinnati-area history is the very reason for our existence and we're working hard to provide the space needed Nineteen Eight-three has been another banner to function adequately and efficiently. The Board of Trustees year for the Cincinnati Historical Society. The well docu- published a Statement of the Society's Facility Needs in December, mented staff reports on all aspects of our activities, on the to which you responded very helpfully with comments and pages that follow clearly indicate the progress we have made. ideas. I'd like to have been able to reply personally to each Our membership has shown a substantial increase over last of you who wrote, but rest assured that all of your comments year. In addition to the longer roster, there has been a are most welcome and carefully considered. Exciting things heartening up-grading of membership category across-the- are evolving in this area. We'll keep you posted as they board. Our frequent and varied activities throughout the develop. year attracted enthusiastic participation. Our newly designed The steady growth and good health of the quarterly, Queen City Heritage, has been very well received.Society rest on the firm foundation of a dedicated Board We are a much more visible, much more useful factor in of Trustees, a very competent staff and a wonderfully the life of the community. -

POST Tilt W 0 RLII* C 0111C1L — Telephone: Gramercy 7-8534 112 E

f. m : m POST tilt W 0 RLII* C 0111C1L _ — Telephone: GRamercy 7-8534 _ 112 E. 19lh STREET. NEW YORK J/ . ¿äät&b, /KO Oswald Garrison Villard Treasurer National Committee Man- W. Hillyer Executive Director Helen Alfred Oscar Ameringer March 6, 1942 Harry Elmer Barnes Irving Barshop Charles F. Boss, Jr. Allan Knight Chalmers President Franklin D. Roosevelt r FILED Travers Clement The White House i Bv v, s. Dorothy Detzer Washington, D. C. »PR 3 Elisabeth Gilman Albert W. Hamilton Dear Mr. Roosevelt: Sidney Hertzberg John Haynes Holmes I have been instructed, "by our Governing Committee Abraham Kaufman to send you the following resolution which was unanimously Maynard C. Krueger adopted at our meeting this week: Margaret I. I^amont l-ayle Lane «Recognizing the real danger of subversive activities W. Jett Lauck among aliens of the West Coast, we nevertheless believe Frederick J. Libby that the Presidential order giving power to generals in Albert J. Livezey command of military departments to evacuate any or all Mrs. Dana Malone aliens or citizens from any districts which may be desig- Lenore G. Marshall nated as military constitutes a danger to American freedom Mrs. Seth M. Milliken and to her reputation for fair play throughout the world Amicus Most far greater than any danger which it is designed to cure. A. J. Muste We, therefore, ask the President for a modification of Kay Newton the order so that, at the least, evacuation of citizens will Mildred Scott Olmsted depend upon evidence immediately applicable to the person Albert W. Palmer or persons evacuated. -

The Emergence and Decline of the Delaware Indian Nation in Western Pennsylvania and the Ohio Country, 1730--1795

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The Research Repository @ WVU (West Virginia University) Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2005 The emergence and decline of the Delaware Indian nation in western Pennsylvania and the Ohio country, 1730--1795 Richard S. Grimes West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Grimes, Richard S., "The emergence and decline of the Delaware Indian nation in western Pennsylvania and the Ohio country, 1730--1795" (2005). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 4150. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/4150 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Emergence and Decline of the Delaware Indian Nation in Western Pennsylvania and the Ohio Country, 1730-1795 Richard S. Grimes Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Mary Lou Lustig, Ph.D., Chair Kenneth A. -

Biological and Water Quality Study of the Middle Scioto River and Select Tributaries, 2010 Delaware, Franklin, Pickaway, and Union Counties

Biological and Water Quality Study of the Middle Scioto River and Select Tributaries, 2010 Delaware, Franklin, Pickaway, and Union Counties Ohio EPA Technical Report EAS/2012-12-12 Division of Surface Water Ecological Assessment Section November 21, 2012 DSW/EAS 2012-12-12 Middle Scioto River and Select Tributaries TSD November 21, 2012 Biological and Water Quality Survey of the Middle Scioto River and Select Tributaries 2010 Delaware, Franklin, Pickaway, and Union Counties November 21, 2012 Ohio EPA Technical Report/EAS 2012-12-12 Prepared by: State of Ohio Environmental Protection Agency Division of Surface Water Central District Office Lazarus Government Center 50 West Town Street, Suite 700 P.O. Box 1049 Columbus, Ohio 43216-1049 State of Ohio Environmental Protection Agency Ecological Assessment Section 4675 Homer Ohio Lane Groveport, OH 43125 Mail to: P.O. Box 1049 Columbus, Ohio 43216-1049 i DSW/EAS 2012-12-12 Middle Scioto River and Select Tributaries TSD November 21, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 12 STUDY AREA DESCRIPTION .............................................................................................. 13 RECOMMENDATIONS ......................................................................................................... 14 RESULTS ............................................................................................................................. -

Child Care Access in 2020

Summer 2019 CHILD CARE ACCESS IN 2020: How will pending state mandates affect availability in Franklin County, Ohio? Abel J. Koury, Ph.D., Jamie O’Leary, MPA, Laura Justice, Ph.D., Jessica A.R. Logan, Ph.D., James Uanhoro INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE Child care provision is a critical service for children and their families, and it can also bolster the workforce and larger economy. For child care to truly be beneficial, however, it must be affordable, accessible, and high quality. A current state requirement regarding child care programming may have enormous implications for many of Ohio’s most vulnerable families who rely on funding for child care. Specifically, by 2020, any Ohio child care provider that accepts Publicly Funded Child Care (PFCC) subsidies must both apply to and receive entry into Ohio’s quality rating and improvement system – Step Up To Quality (SUTQ) (the “2020 mandate”). The purpose of this paper is two-fold. First, we aim to provide an in-depth examination of the availability of child care in Franklin County, Ohio, with a specific focus on PFCC-accepting programs, and explore how this landscape may change in July of 2020. Second, we aim to examine the locations of programs that are most at risk for losing child care sites, highlighting possible deserts through the use of mapping. Crane Center for Early Childhood Research and Policy Improving children’s well-being through research, practice, and policy.1 2020 SUTQ Mandate: What is at stake? According to an analysis completed by Franklin County Jobs and Family Services (JFS), if the 2020 mandate went into effect today, over 21,000 young children would lose their care (Franklin County Jobs and Family Services, 2019).