Center for Institutional Reform and the Informal Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Covid-19 Nepal: Preparedness and Response Plan (Nprp)

COVID-19 NEPAL: PREPAREDNESS AND RESPONSE PLAN (NPRP) April 2020 NPRP for COVID-19 | 2 COVID-19 Nepal: Preparedness and Response Plan (NPRP) Introduction The COVID crisis affecting the world today requires a level of response that goes beyond the capacity of any country. As the UN Secretary-General said: “More than ever before, we need solidarity, hope and the political will and cooperation to see this crisis through together”. The Government of Nepal is putting in place a series of measures to address the situation, but more needs to be done, and the international solidarity is required to ensure that the country is fully prepared to face the pandemic and address its impact in all sectors. The Nepal Preparedness and Response Plan (NPRP) lays out the preparedness actions and key response activities to be undertaken in Nepal, based on the trends and developments of the global COVID-19 pandemic. The plan outlines two levels of interventions; one that is the preparedness that should take place at the earliest possible and that constitutes an investment in Nepal’s health systems that will in any case benefit the people of Nepal, regardless of the extent of the COVID-19 pandemic in the territory. The second level is the effective response, across sectors, to an estimated caseload of 1500 infected people and 150,000 collaterally affected people. This can then be scaled up in case there is a vast increase in number of infected and affected people, beyond the original scenario of 1500 patients. Nepal is also vulnerable to natural disasters, including seasonal floods and landslides. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Name : Babita Basnet Date of Birth : 29 April, 1971, Khotang, Nepal Address : Aanamn Nagar, Kathmandu, Nepal P.O.Box: 13293/897 Mobile: 9851075373 Tel. 4770209/5538549/4222172 Fax: 5000181 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Occupation : Journalism Marital Status : Married Nationality : Nepali Academic Qualification : S.L.C. - 1984 (H.M.G. Board) I.A. - 1993 (Tribhuwan University) B.A.- 1996 (Tribhuwan University) Language : Nepali, Hindi and English Travel : India, USA, Philippines, Hongkong, Thailand, Singapore, Maldivs, Pakistan, Srilanka, Slovenia, Bangaladesh ,China, Belgium, The Netherland Editor : Ghatana Ra Bichar Weekly President : Sancharika Samuha (Forum of Women Journalists in Nepal) General Secretary : International Press Institute (Nepal Chapter) Joint Secretary : South Asian Editors Forum (SAEF) Member : Special Task Force on Draft Preparation for Right to Information Act formed by the Government of Nepal on September 2006. i Training Background (a) Journalism Training from Indian Institute of Mass Communication,New Delhi-1993 (b) United Nations Training Programme for Broadcasters and Journalists from Developing Countries, New York - 1994 (c) Economic Reporting Training, Kathmandu - 1995 Experience Correspondent : Nepalipatra Weekly 1990-1997 Programme Presenter And Editor : Radio Nepal, News and Current Affairs Programme, 1996-1998 Publication Chief : Legal Aid and Concultancy Center (LACC)- 1997 (Part Time:Sep.to Dec.), Co-ordinator : Communication for Equality and Solidarity (Seminar)- Kathmandu, 1997 Co-ordinator : News Reporting on Women Issues (Seminar)- Butwal, 1998 Co-ordinator : Role of Women in Environment Conservation (Seminar) – Kathmandu, 1998 Joint Secretary : South Asian Free Media Association (SAFMA) Nepal Chapter Asst.Co-ordinator : Women's Participation in Election Political Intervention Empowerment (Training) - Palpa/Nepalgunj / Dhangadhi/Dharan and Kathmandu, 1997 Co-ordinator : Media Compaign on Violence against women and Girl Issue. -

Logistics Capacity Assessment Nepal

IA LCA – Nepal 2009 Version 1.05 Logistics Capacity Assessment Nepal Country Name Nepal Official Name Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal Regional Bureau Bangkok, Thailand Assessment Assessment Date: From 16 October 2009 To: 6 November 2009 Name of the assessors Rich Moseanko – World Vision International John Jung – World Vision International Rajendra Kumar Lal – World Food Programme, Nepal Country Office Title/position Email contact At HQ: [email protected] 1/105 IA LCA – Nepal 2009 Version 1.05 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Country Profile....................................................................................................................................................................3 1.1. Introduction / Background.........................................................................................................................................5 1.2. Humanitarian Background ........................................................................................................................................6 1.3. National Regulatory Departments/Bureau and Quality Control/Relevant Laboratories ......................................16 1.4. Customs Information...............................................................................................................................................18 2. Logistics Infrastructure .....................................................................................................................................................33 2.1. Port Assessment .....................................................................................................................................................33 -

Nepal – Maoists – Chitwan – State Protection – Local Government – Ward Chairmen

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: NPL17502 Country: Nepal Date: 2 September 2005 Keywords: Nepal – Maoists – Chitwan – State protection – Local government – Ward Chairmen This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Can you provide information on the activities of Maoists in Chitwan and the ability of the authorities to provide protection for individuals against threats from Maoists? 2. Do the Maoists have an office in Chitwan? Letter head paper or contact address? 3. What is a Ward and a Ward Chairman? 4. Is there evidence of the Maoists targeting members of Municipal councils or Ward Chairmen? RESPONSE 1. Can you provide information on the activities of Maoists in Chitwan and the ability of the authorities to provide protection for individuals against threats from Maoists? Activities A December 2002 Research Response provides information on Maoists in Chitwan suggesting it is a quiet area and they are mainly active in remote villages (RRT Country Research 2002 Research Response NPL17502, 24 December, question 1 – Attachment 1). A recent news item from the al Jazeera website refers to the Maoist-controlled district of Chitwan (‘Nepal blast triggers hunt for Maoists’ 2005, al Jazeera website, source: AFP, 6 June http://english.aljazeera.net/NR/exeres/9F7BE0A5-E320-4C5B-BD03- 7151D63A574F.htm - accessed 1 September 2005 - Attachment 2). -

1.2 District Profile Kailali English Final 23 March

"Environmnet-friendly Development, Maximum Use of Resources and Good Governance Overall Economic, Social and Human Development; Kailali's Pridefulness" Periodic District Development Plan (Fiscal Year 2072/073 − 2076/077) First Part DISTRICT PROFILE (Translated Version) District Development Committee Kailali March 2015 Document : Periodic District Development Plan of Kailali (F/Y 2072/73 - 2076/77) Technical Assistance : USAID/ Sajhedari Bikaas Consultant : Support for Development Initiatives Consultancy Pvt. Ltd. (SDIC), Kathmandu Phone: 01-4421159, Email : [email protected] , Web: www.sdicnepal.org Date March, 2015 Periodic District Development Plan (F/Y 2072/073 - 2076/77) Part One: District Profile Abbreviation Acronyms Full Form FY Fiscal year IFO Area Forest Office SHP Sub Health Post S.L.C. School Leaving Certificate APCCS Agriculture Production Collection Centres | CBS Central Bureau of Statistics VDC Village Development Committee SCIO Small Cottage Industry Office DADO District Agriculture Development Office DVO District Veterinary Office DSDC District Sports Development Committee DM Dhangadhi Municipality PSO Primary Health Post Mun Municipality FCHV Female Community Health Volunteer M Meter MM Milimeter MT Metric Ton TM Tikapur Municipality C Centigrade Rs Rupee H Hectare HPO Health Post HCT HIV/AIDS counselling and Testing i Periodic District Development Plan (F/Y 2072/073 - 2076/77) Part One: District Profile Table of Contents Abbreviation .................................................................................................................................... -

Flood Assessment Report2020 Kailali 03Aug2020.Pdf

NEPAL 72-hour assessment VERSION_1 Contents may change based on updated information 03 August 2020 Flood in Kailali| July 2020 Priority Populations for Food Assistance Total 21,900 Priority 3 5,400 Priority 2 8,100 Priority 1 8,400 Children Heavy rainfall on 28-29 July 2020 caused flooding in Priority Palika Households Population PLW under 5 Sudurpaschim Province Terai, affecting mainly Kailali 1 3 1,400 8,400 800 200 district. The disaster damaged assets, including houses, water and sanitation infrastructure, food stocks and 2 2 1,400 8,100 800 200 agricultural production, which negatively impacted food security in the district. An estimated 21,900 people’s food 3 3 1,100 5,400 500 100 security is significantly affected as a result of the flooding, Total 8 3,900 21,900 2,100 500 of which 8,400 people, or 1,400 households, are considered to be in most need of assistance. Note: The numbers presented in the Map and Table are estimated based on the However, the satellite image received in 2 August 2020 flood inundation at the peak, received from Sentiel-1 SAR on 29 July and overlaying the pre-crisis vulnerability indicators of these Palikas. Priority 1 and 2 from Sentiniel-1 SAR (see Inundation Area 2) showed that are inneed of immediate assistanceduethe severity of situation. water level is receding in most of the flooded areas. This, WFP has started field assessment in the affected areas to verify and understand together with field assessment results, can influence the the impactand estimate the need as part of 72-hour approach methodology. -

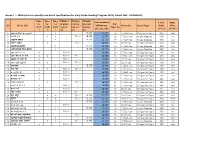

Annex 1 : - Srms Print Run Quantity and Detail Specifications for Early Grade Reading Program 2019 ( Cohort 1&2 : 16 Districts)

Annex 1 : - SRMs print run quantity and detail specifications for Early Grade Reading Program 2019 ( Cohort 1&2 : 16 Districts) Number Number Number Titles Titles Titles Total numbers Cover Inner for for for of print of print of print # of SN Book Title of Print run Book Size Inner Paper Print Print grade grade grade run for run for run for Inner Pg (G1, G2 , G3) (Color) (Color) 1 2 3 G1 G2 G3 1 अनारकल�को अꅍतरकथा x - - 15,775 15,775 24 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 2 अनौठो फल x x - 16,000 15,775 31,775 28 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 3 अमु쥍य उपहार x - - 15,775 15,775 40 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 4 अत� र बु饍�ध x - 16,000 - 16,000 36 21x27 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 5 अ쥍छ�को औषधी x - - 15,775 15,775 36 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 6 असी �दनमा �व�व भ्रमण x - - 15,775 15,775 32 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 7 आउ गन� १ २ ३ x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 8 आज मैले के के जान� x x 16,000 16,000 - 32,000 16 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 9 आ굍नो घर राम्रो घर x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 21x27 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 10 आमा खुसी हुनुभयो x x 16,000 16,000 - 32,000 20 21x27 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 11 उप配यका x - - 15,775 15,775 20 14.8x21 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4X4 12 ऋतु गीत x x 16,000 16,000 - 32,000 16 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 13 क का �क क� x 16,000 - - 16,000 16 14.8x21 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 14 क दे�ख � स륍म x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 2X0 2x2 15 कता�तर छौ ? x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 2X0 2x2 -

Integrated Biological and Behavioral Surveillance Survey (IBBS) Among Female Sex Workers in 22 Terai Highway Districts of Nepal

Integrated Biological and Behavioral Surveillance Survey (IBBS) among Female Sex Workers in 22 Terai Highway Districts of Nepal ASHA Project Family Health International /Nepal Baluwatar P.O. Box 8803 Kathmandu, Nepal July 2009 i In July 2011, FHI became FHI 360. FHI 360 is a nonprofit human development organization dedicated to improving lives in lasting ways by advancing integrated, locally driven solutions. Our staff includes experts in health, education, nutrition, environment, economic development, civil society, gender, youth, research and technology – creating a unique mix of capabilities to address today’s interrelated development challenges. FHI 360 serves more than 60 countries, all 50 U.S. states and all U.S. territories. Visit us at www.fhi360.org. ACNielsen Nepal Pvt. Ltd. PO Box: 1784, Ravi Bhawan, Kalimati, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: 977 1 4273890 / 4281880; Fax: 977 1 4283858 Website: http://www.nielsen.com In Collaboration with STD/AIDS Counseling and Training Services Pyukha, Kathmandu, Nepal And National Reference Laboratory Rara Complex, New Baneshwor Family Health International/Nepal USAID Cooperative Agreement #367-A-00-06-00067-00 Strategic Objective No. 9 & 11 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS _____________________________________________________ We would like to extend our gratitude to Family Health International/Nepal for providing us with the opportunity to conduct such a meaningful and prestigious study. The ACNielsen study team would like to express special thanks to Ms. Jacqueline McPherson, Country Director, FHI/Nepal, Mr. Satish Raj Pandey, Deputy Director, FHI/Nepal, Dr. Laxmi Bilas Acharya, Team Leader – Strategic Information Unit, FHI/Nepal and Mahesh Shrestha, M&E Officer, FHI/Nepal for their support. Dr. Laxmi Bilas Acharya deserves special credit for the guidance and support provided during the entire the course of the study. -

Technical Assistance Consultant's Report Nepal: Far Western Region

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: TA 8817 January 2017 Nepal: Far Western Region Urban Development Project (Volume 2) Prepared by: Michael Green London, United Kingdom For: Ministry of Urban Development Department of Urban Development and Building Construction This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. Government of Nepal Ministry of Urban Development Second Integrated Urban Development Project (IUDP2) (PPTA 8817–NEP) Draft Final Report Discussion Note # 1 Economic and Urban Development Vision for Far Western Terai Region August 2015 Discussion Note # 1 Economic and Urban Development Vision for Far Western Terai Region Part A : Economic Development Vision and Strategy TA 8817-NEP: Second Integrated Urban Development Project Discussion Note # 1 Economic and Urban Development Vision for Far Western Terai Region Part A : Economic Development Vision and Strategy Contents 1 Context 1 1.1 Purpose of the Vision 1 1.2 Nepal – A gifted country 1 1.3 The Terai – the bread basket of Nepal 2 1.4 Far West Nepal – Sundar Sudur Paschim 3 2 Prerequisites for Transformational Growth and Development 4 2.1 The Constitution and decentralization of governance 4 2.2 Strengthening Nepal’s economic links with India 4 2.3 Developing Transportation 5 2.3.1 Developing strong transport -

Table of Province 07, Preliminary Results, Nepal Economic Census

Number of Number of Persons Engaged District and Local Unit establishments Total Male Female Bajura District 3,901 11,133 6,408 4,725 70101HIMALI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 338 1,008 487 521 70102GAUMUL RURAL MUNICIPALITY 263 863 479 384 70103BUDHINANDA MUNICIPALITY 596 1,523 899 624 70104SWAMI KARTIK RURAL MUNICIPALITY 187 479 323 156 70105JAGANNATH RURAL MUNICIPALITY 277 572 406 166 70106BADIMALIKA MUNICIPALITY 836 2,538 1,297 1,241 70107CHHEDEDAHA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 498 1,626 1,045 581 70108BUDHIGANGA MUNICIPALITY 531 1,516 909 607 70109TRIBENI MUNICIPALITY 375 1,008 563 445 Bajhang District 6,215 18,098 10,175 7,923 70201SA PAL RURAL MUNICIPALITY 47 138 74 64 70202BUNGAL MUNICIPALITY 740 2,154 1,262 892 70203SURMA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 256 804 451 353 70204TALKOT RURAL MUNICIPALITY 442 1,386 728 658 70205MASTA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 488 1,258 710 548 70206JAYAPRITHBI MUNICIPALITY 1,218 4,107 2,364 1,743 70207CHHABIS PATHIBHARA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 492 1,299 772 527 70208DURGATHALI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 420 1,157 687 470 70209KEDARSYUN RURAL MUNICIPALITY 640 1,918 935 983 70210BITTHADCHIR RURAL MUNICIPALITY 558 1,696 873 823 70211THALARA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 451 912 641 271 70212KHAPTAD CHHANNA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 463 1,269 678 591 Darchula District 3,417 13,319 7,490 5,829 70301BYAS RURAL MUNICIPALITY 215 536 361 175 70302DUHUN RURAL MUNICIPALITY 194 491 328 163 70303MAHAKALI MUNICIPALITY 1,171 4,574 2,258 2,316 70304NAUGAD RURAL MUNICIPALITY 230 1,051 754 297 70305APIHIMAL RURAL MUNICIPALITY 141 1,067 522 545 70306MARMA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 264 1,242 566 -

Nepal Water Supply Corporation Water Supply Hour of Different Branches

Nepal Water Supply Corporation Water Supply hour of Different Branches 1.Branch Name: Taulihawa Branch Water Supply Supply hour S.N. Place Remarks. Area Morning Day Evening 1 Taulihawa Kapilbastu Municipality 5:00 to 8:00 5:00 to7:00 2.Branch Name: Dharan Branch Water Supply Supply hour S.N. Place Remarks. Area Morning Day Evening 1 Dharan Dharan Municipality Ward no. 04 2:00 to 5:00 Ward no. 12 2:00 to 5:00 Ward no. 13 2:00 to 5:00 Ward no. 13 2:00 to 5:00 Ward no. 15 2:00 to 5:00 Ward no. 16 2:00 to 5:00 Other remaining wards 2:00 to 6:00 2:00 to 5:00 3.Branch Name: Bhairahawa Branch Water Supply Supply hour S.N. Place Remarks. Area Morning Day Evening 1 Bhairahawa Siddhartha nagar Municipality 5:00 to 9:00 12:00 to 1:00 5:00 to7:00 4.Branch Name: Gaur Branch Water Supply Supply hour S.N. Place Remarks. Area Morning Day Evening 1 Gaur Gaur Municipality 5:00 to 9:30 12:00 to 1:30 6:00 to 9:00 5.Branch Name: Biratnagar Branch Water Supply Supply hour S.N. Place Remarks. Area Morning Day Evening Biratnagar Sub Metropolitan 1 Biratnagar city Devkota Pump station 4:00 to 9:00 12:00 to 2:00 5:00 to 9:00 Tinpani pump Station 4:00 to 9:00 12:00 to 2:00 5:00 to 9:00 Munalpath pump satation 4:00 to 10:00 12:00 to 2:00 3:00 to 10:00 6.Branch Name: Krishnanagar Branch Water Supply Supply hour S.N. -

Tourism Stimulated Prosperity and Peace in Provincial Destination: an Appraisal of Far West Nepal

Journal of Tourism & Hospitality Educa on 9 (2019) 30-39 Journal of Tourism & Hospitality Education Tourism Stimulated Prosperity and Peace in Provincial Destination: An Appraisal of Far West Nepal Pranil Kumar Upadhayaya Tourism Research and Development Consultant [email protected] Abstract Tourism thrives in peace. It is a major benefi ciary of peace. Nevertheless, it is also be a benefactor to peace if it is planned, developed and managed from the perspectives of building socio-economic foundation, environmental wellness and socio-cultural contacts and communications. Such elements of peace through tourism are applicable to all destinations including provincial, national, local or international. Th is paper presents the general conceptual foundation on tourism stipulated prosperity and peace and relates this feature with Far West Nepal which is a newly established provincial destination in Nepal. It argues that peace related objectives of tourism can be achieved through planned development, operation and purposeful management of tourism directed to enhancing socio-economic foundations and intercultural relations. Th e responsibilities for such aspects lie at all actors (hosts and guests) and all levels of government like local, national and provincial. Th is aspect is truly applicable in Far West a newly growing regional tourist destination where the provincial government is on board with people’s mandate and necessary resources. Keywords: Tourism, prosperity and peace, socio-economic foundation, far west destination Copyright © 2019 Author Published by: AITM School of Hotel Management, Knowledge Village, Khumaltar, Lalitpur, Nepal ISSN 2467-9550 Upadhayaya: Tourism S mulated Prosperity and Peace in Provincial Des na on... 31 Introduction Conceptual foundation on tourism stimulated prosperity and peace Global tourism, arguably the world’s most-important economic sector, has drawn growing inspiration and hope for achieving prosperity and peace.