Andrei Codrescu's Tropical Rediscovery of Romanian Culture in the Hole in the Flag

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romania's Cultural Wars: Intellectual Debates About the Recent Past

ROMANIA'S CULTURAL WARS : Intellectual Debates about the Recent Past Irina Livezeanu University of Pittsburgh The National Council for Eurasian and East European Researc h 910 17`" Street, N.W . Suite 300 Washington, D.C. 2000 6 TITLE VIII PROGRAM Project Information* Contractor : University of Pittsburgh Principal Investigator: Irina Livezeanu Council Contract Number : 816-08 Date : March 27, 2003 Copyright Informatio n Individual researchers retain the copyright on their work products derived from research funde d through a contract or grant from the National Council for Eurasian and East European Researc h (NCEEER). However, the NCEEER and the United States Government have the right to duplicat e and disseminate, in written and electronic form, reports submitted to NCEEER to fulfill Contract o r Grant Agreements either (a) for NCEEER's own internal use, or (b) for use by the United States Government, and as follows : (1) for further dissemination to domestic, international, and foreign governments, entities and/or individuals to serve official United States Government purposes or (2) for dissemination in accordance with the Freedom of Information Act or other law or policy of th e United States Government granting the public access to documents held by the United State s Government. Neither NCEEER nor the United States Government nor any recipient of this Report may use it for commercial sale . * The work leading to this report was supported in part by contract or grant funds provided by th e National Council for Eurasian and East European Research, funds which were made available b y the U.S. Department of State under Title VIII (The Soviet-East European Research and Trainin g Act of 1983, as amended) . -

Research Project for the Subject

The Creator vs. the Creative Man in Romanian Literature (The period between the wars vs. the communist regime) Bagiu, Lucian Published in: Annales Universitatis Apulensis. Series Philologica 2008 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Bagiu, L. (2008). The Creator vs. the Creative Man in Romanian Literature (The period between the wars vs. the communist regime). Annales Universitatis Apulensis. Series Philologica, 9(2), 121-130. http://www.uab.ro/reviste_recunoscute/index.php?cale=2008_tom2 Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 The Creator vs. the Creative Man in Romanian Literature (The period between the wars vs. the communist regime) - Research Project - asist. -

The Spirit of the People Will Be Stronger Than the Pigs’ Technology”

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE November 2017 “THE SPIRIT OF THE PEOPLE WILL BE STRONGER THAN THE PIGS’ TECHNOLOGY” An exhibition, a symposium, and a month-long series of events re-examining the interdependent legacies of revolutionary poetry and the militant left in the United States, with a spotlight on Allen Van Newkirk’s Guerrilla: Free Newspaper of the Streets (Detroit, Mich. & New York City: 1967-1968) and the recent & upcoming 50th anniversaries of the founding of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, Calif. (1966) and the White Panther Party in Detroit, Mich. (1968) including a presentation of rare ephemera from both groups. Exhibition: 9 November – 29 December 2017 @ Fortnight Institute Symposium: 17 November 2017 @ NYU Page 1 of 6 E XHIBITION A complete run of Guerrilla: Free Newspaper of the Streets serves as the focal point for an exhibition of r evolutionar y le fti s t posters , bro adsides, b oo ks, and ep hemera, ca. 196 4-197 0, a t East Villag e ( Manhattan) a rt gall e ry Fortnight Institute, opening at 6 pm on Thu rsd ay, Novemb er 9 , 2017 a nd c ontinuing through Sun day, December 29. Th e displa y also inc lude s rare, orig inal print m ate rials a nd p osters fro m the Bl ack Pan ther Party, Whi t e Panther Party , Young Lords a nd ot her revolu tion ary g roups. For t he d u ration of the exhib itio n, Fortnig ht Institute will also house a readin g room stock ed with cha pbooks and pa perbacks from leftist mili tant poets o f the era, many of w hose works we re p rinted in G uerrill a, includ ing LeRo i Jones, Diane Di P rima, M arga ret Ran dall, Reg is Deb ray an d o thers. -

Communism and Post-Communism in Romania : Challenges to Democratic Transition

TITLE : COMMUNISM AND POST-COMMUNISM IN ROMANIA : CHALLENGES TO DEMOCRATIC TRANSITION AUTHOR : VLADIMIR TISMANEANU, University of Marylan d THE NATIONAL COUNCIL FO R EURASIAN AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARC H TITLE VIII PROGRA M 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, N .W . Washington, D .C . 20036 LEGAL NOTICE The Government of the District of Columbia has certified an amendment of th e Articles of Incorporation of the National Council for Soviet and East European Research changing the name of the Corporation to THE NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR EURASIAN AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARCH, effective on June 9, 1997. Grants, contracts and all other legal engagements of and with the Corporation made unde r its former name are unaffected and remain in force unless/until modified in writin g by the parties thereto . PROJECT INFORMATION : 1 CONTRACTOR : University of Marylan d PR1NCIPAL 1NVEST1GATOR : Vladimir Tismanean u COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 81 1-2 3 DATE : March 26, 1998 COPYRIGHT INFORMATIO N Individual researchers retain the copyright on their work products derived from research funded by contract with the National Council for Eurasian and East European Research . However, the Council and the United States Government have the right to duplicate an d disseminate, in written and electronic form, this Report submitted to the Council under thi s Contract, as follows : Such dissemination may be made by the Council solely (a) for its ow n internal use, and (b) to the United States Government (1) for its own internal use ; (2) for further dissemination to domestic, international and foreign governments, entities an d individuals to serve official United States Government purposes ; and (3) for dissemination i n accordance with the Freedom of Information Act or other law or policy of the United State s Government granting the public rights of access to documents held by the United State s Government. -

Between Denial and "Comparative Trivialization": Holocaust Negationism in Post-Communist East Central Europe

Between Denial and "Comparative Trivialization": Holocaust Negationism in Post-Communist East Central Europe Michael Shafir Motto: They used to pour millet on graves or poppy seeds To feed the dead who would come disguised as birds. I put this book here for you, who once lived So that you should visit us no more Czeslaw Milosz Introduction* Holocaust denial in post-Communist East Central Europe is a fact. And, like most facts, its shades are many. Sometimes, denial comes in explicit forms – visible and universally-aggressive. At other times, however, it is implicit rather than explicit, particularistic rather than universal, defensive rather than aggressive. And between these two poles, the spectrum is large enough to allow for a large variety of forms, some of which may escape the eye of all but the most versatile connoisseurs of country-specific history, culture, or immediate political environment. In other words, Holocaust denial in the region ranges from sheer emulation of negationism elsewhere in the world to regional-specific forms of collective defense of national "historic memory" and to merely banal, indeed sometime cynical, attempts at the utilitarian exploitation of an immediate political context.1 The paradox of Holocaust negation in East Central Europe is that, alas, this is neither "good" nor "bad" for the Jews.2 But it is an important part of the * I would like to acknowledge the support of the J. and O. Winter Fund of the Graduate Center of the City University of New York for research conducted in connection with this project. I am indebted to friends and colleagues who read manuscripts of earlier versions and provided comments and corrections. -

Absurdistan Refacut Cu Headere Ultimul.P65

Dorin Tudoran (n. 30 iunie 1945, Timi[oara). Absolvent al Facult\]ii de Limb\ [i Literatur\ Român\ a Universit\]ii din Bucure[ti, pro- mo]ia 1968. Este Senior Director, pentru Comunicare [i Cercetare, membru al conducerii executive a Funda]iei Interna]ionale IFES, Washington D.C., Statele Unite, [i redactor-[ef al revistei democracy at large. C\r]i de poezie: Mic tratat de glorie (1973), C`ntec de trecut Akheronul (1975), O zi `n natur\ (1977), Uneori, plutirea (1977), Respira]ie artificial\ (1978), Pasaj de pietoni (1978), Semne particulare (antologie, 1979), De bun\ voie, autobiografia mea (1986), Ultimul turnir (antologie, 1992), Optional Future (1988), Viitorul Facultativ/Optional Future (1999), T`n\rul Ulise (antologie, 2000). C\r]i de publicistic\: Martori oculari (`n colaborare cu Eugen Seceleanu, 1976), Biografia debuturilor (1978), Nostalgii intacte (1982), Adaptarea la realitate (1982), Frost or Fear? On the Condition of the Romanian Intelectual (traducere [i prefa]\ de Vladimir Tism\neanu, 1988), Onoarea de a `n]elege (antologie, 1998), Kakistokra]ia (1998). Pentru unele dintre c\r]ile sale, autorul a primit Premiul Uniunii Scriitorilor (1973, 1977, 1998), Marele Premiu al Asocia]iilor Scriitorilor Profesioni[ti ASPRO (1998), Premiul Uniunii Scriitorilor din Republica Moldova (1998), Premiul revistei Cuv`ntul Superlativele anului (1998). I s-a decernat un Premiu Special al Uniunii Scriitorilor (1992) [i este laureatul Premiului ALA pe anul 2001. www.polirom.ro © 2006 by Editura POLIROM Editura POLIROM Ia[i, B-dul Carol I nr. 4, P.O. BOX 266, 700506 Bucure[ti, B-dul I.C. Br\tianu nr. 6, et. -

A Writer's Calendar

A WRITER’S CALENDAR Compiled by J. L. Herrera for my mother and with special thanks to Rose Brown, Peter Jones, Eve Masterman, Yvonne Stadler, Marie-France Sagot, Jo Cauffman, Tom Errey and Gianni Ferrara INTRODUCTION I began the original calendar simply as a present for my mother, thinking it would be an easy matter to fill up 365 spaces. Instead it turned into an ongoing habit. Every time I did some tidying up out would flutter more grubby little notes to myself, written on the backs of envelopes, bank withdrawal forms, anything, and containing yet more names and dates. It seemed, then, a small step from filling in blank squares to letting myself run wild with the myriad little interesting snippets picked up in my hunting and adding the occasional opinion or memory. The beginning and the end were obvious enough. The trouble was the middle; the book was like a concertina — infinitely expandable. And I found, so much fun had the exercise become, that I was reluctant to say to myself, no more. Understandably, I’ve been dependent on other people’s memories and record- keeping and have learnt that even the weightiest of tomes do not always agree on such basic ‘facts’ as people’s birthdays. So my apologies for the discrepancies which may have crept in. In the meantime — Many Happy Returns! Jennie Herrera 1995 2 A Writer’s Calendar January 1st: Ouida J. D. Salinger Maria Edgeworth E. M. Forster Camara Laye Iain Crichton Smith Larry King Sembene Ousmane Jean Ure John Fuller January 2nd: Isaac Asimov Henry Kingsley Jean Little Peter Redgrove Gerhard Amanshauser * * * * * Is prolific writing good writing? Carter Brown? Barbara Cartland? Ursula Bloom? Enid Blyton? Not necessarily, but it does tend to be clear, simple, lucid, overlapping, and sometimes repetitive. -

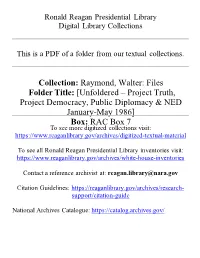

Unfoldered – Project Truth, Project Democracy, Public Diplomacy

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: Raymond, Walter: Files Folder Title: [Unfoldered – Project Truth, Project Democracy, Public Diplomacy & NED January-May 1986] Box: RAC Box 7 To see more digitized collections visit: https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digitized-textual-material To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/white-house-inventories Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/research- support/citation-guide National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ WITHDRAWAL SHEET Ronald Reagan Library Collection Name RAYMOND, w ALTER: FILES Withdrawer SMF 7/14/2011 File Folder [PROJECT TRUTH, PROJECT DEMOCRACY, PUBLIC FOIA DIPLOMACY, AND NED JANUARY 1986-MAY 1986] M430 Box Number 7 LAMB, CHRISTOPHER 72 ID DocType Document Description Noof Doc Date Restrictions 115205 MEMO REICHLER TO ACTIVE MEASURES 5 2/25/1986 Bl B3 WORKING GROUP RE ACTIVE MEASURES MEMO #3 OF 1986 p 11/21/2002 F95-041/2 #78; PAR M430/1 #115205 3/31/2015 115206 MINUTES ACTIVE MEASURES WORKING GROUP 4 2/27/1986 Bl B3 2/27 /86 MEETING p 11/21/2002 F95-041/2 #78; PAR M430/1 B6 #115206 3/31/2015 115208 NOTE SITUATION ROOM RE SOVIET 1 2/25/1986 Bl PROPAGANDA EFFORTS D 7/19/2000 F95-041/2 #80; PAR M430/1 #115208 3/31/2015 115211 CABLE 150045Z FEB 86 3 2/15/1986 Bl B3 D 7/3/2000 F95-041/2 #81; UPHELD M430/2 #115211 3/31/2015 115213 MINUTES ACTIVE MEASURES WORKING GROUP 3 5/27/1986 Bl B3 5/22/86 MEETING p 11/21/2002 F95-041/2 #82; PAR M430/1 B6 #115213 3/31/2015 Freedom of Information Act - (5 U.S.C. -

Luca Centenary Issue 1913 – 1994

!!! MAST HEAD ! Publisher: Contra Mundum Press Location: New York & Berlin Editor-in-Chief: Rainer J. Hanshe Guest Editor: Allan Graubard PDF Design: Giuseppe Bertolini Logo Design: Liliana Orbach Advertising & Donations: Giovanni Piacenza (To contact Mr. Piacenza: [email protected]) CMP Website: Bela Fenyvesi & Atrio LTD. Design: Alessandro Segalini Letters to the editors are welcome and should be e-mailed to: [email protected] Hyperion is published three times a year by Contra Mundum Press, Ltd. P.O. Box 1326, New York, NY 10276, U.S.A. W: http://contramundum.net For advertising inquiries, e-mail Giovanni Piacenza: [email protected] Contents © 2013 by Contra Mundum Press, Ltd. and each respective author. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Contra Mundum Press, Ltd. After two years, all rights revert to the respective authors. If any work originally published by Contra Mundum Press is republished in any format, acknowledgement must be noted as following and a direct link to our site must be included in legible font (no less than 10 pt.) at the bottom of the new publication: “Author/Editor, title, year of publication, volume, issue, page numbers, originally published by Hyperion. Reproduced with permission of Contra Mundum Press, Ltd.” Vol. VII, No. 3 (fall 2013) Ghérasim Luca Centenary Issue 1913 – 1994 Jon Graham, -

CONFLICTS in CODRESCU's the BLOOD COUNTESS by YUDA SABRANG

CONFLICTS IN CODRESCU’S THE BLOOD COUNTESS A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Cultural Sciences Hasanuddin University In Partial Fulfillment to Obtain Sarjana Sastra Degree By YUDA SABRANG ‘AINAN LU’LU ISMAIL F21111106 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF CULTURAL SCIENCES HASANUDDIN UNIVERSITY MAKASSAR 2018 iii iv v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Alhamdulillahirabbil ‘alamin, first of all, I want to express my deepest gratitude to Allah SWT for the blessing, guidance and also the strength to accomplish my thesis, and also for my Prophet Muhammad SAW, the righteous messenger of Allah SWT Who is the leader that guiding us into the right path. During the process on working the thesis, I get some help, guidance, support, advice and motivation from many people. So for the first, I want to say thanks for my beloved parents. The deserve to receive my very special praise for their endless prayers and support in every aspect. I hope both of you can finally proud of me because of my achievement. Seconly, I gratefully acknowledge Drs. Husain Hasyim, M.Hum who is my first consultant for his supervision, guidance and also advices since the beginning of my research. I also want to sent my gratitude to my second consultant, Abbas, S.S, M.Hum who always patiently and gently supervised me. Both of you are the best, thank yoy very much. Great thanks to both Armien Harry Zainuddin and Arga Maulana. The people who helped in giving the ideas support the writing of this thesis. May God Bless both of you. Also, I would like to thank my examiners, Dr. -

Christian Church8

www.ssoar.info From periphery to centre: the image of Europe at the Eastern Border of Europe Şipoş, Sorin (Ed.); Moisa, Gabriel (Ed.); Cepraga, Dan Octavian (Ed.); Brie, Mircea (Ed.); Mateoc, Teodor (Ed.) Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Konferenzband / collection Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Şipoş, S., Moisa, G., Cepraga, D. O., Brie, M., & Mateoc, T. (Eds.). (2014). From periphery to centre: the image of Europe at the Eastern Border of Europe. Cluj-Napoca: Ed. Acad. Română. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168- ssoar-400284 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de Edited by: Sorin §ipo§, Gabriel Moisa, Dan Octavian Cepraga, Mircea Brie, Teodor Mateoc From Periphery to Centre. The Image of Europe at the Eastern Border of Europe Editorial committee: Delia-Maria Radu Roxana Iva^ca Alexandra Bere IonuJ Ciorba Romanian Academy Center for Transylvanian Studies Cluj-Napoca 2014 Descrierea CIP a Bibliotecii Nationale a României From periphery to centre : the image of Europe at the Eastern border of Europe/ Sorin Çipoç, Gabriel Moisa, Dan Octavian Cepraga, Mircea Brie (ed.). - Cluj-Napoca : Editura Academia Românâ. Centrul de Studii Transilvane, 2014 ISBN 978-973-7784-97-1 I. Çipoç, Sorin (ed.) II. Moisa, Gabriel (ed.) III. Cepraga, Dan Octavian (ed.) IV. Brie, Mircea (ed.) 930 Volume published with the support of Bihor County Council The volume gathers the papers presented at the international symposium From Periphery to Centre. -

GEO) Conference

Global Electoral Organization (GEO) Conference March 27-29, 2007 FINAL REPORT Global Electoral Organization (GEO) Conference Final Report TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Summary…………………………………………………………….….2 II. Objectives and Outcomes………………………………………………..……...3 III. Conclusions……………………………………………………………………….….11 IV. Annexes a. Presentations…………….…………………………………………………....12 b. List of Participants ……………………………………………….………….16 c. Meeting Minutes………..……………………………………………..……..24 d. Conference Program.………………………………………………………..40 e. Photographs…………….……………………………………………………...42 1 Global Electoral Organization (GEO) Conference March 27-29, 2007 – Washington, DC EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Among the many challenges confronting democratic nations, ensuring citizens’ right to free, fair and transparent elections ranks especially high. In election commissions around the world, talented and committed professionals often find themselves with limited access to a network of peers they can consult for professional advice. The conferences of the Global Electoral Organization (GEO) regularly provide senior election officials and democracy practitioners a much needed opportunity to gather together in person and share common experiences and find solutions to issues in election management. IFES, an international nonprofit organization that supports the building of democratic societies, hosted the fourth gathering of the GEO network at the Westin Grand in Washington, D.C., from March 27–29, 2007. This year’s GEO conference also received support from 11 other leading international and government organizations and the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). Attendees at this year’s GEO conference included more than 250 international electoral systems experts, representatives from national and regional electoral management bodies, universities, and the diplomatic and donor communities from over 50 countries. This final report highlights the extent to which the 2007 GEO Conference met various conference objectives set by the host, IFES.