Durga Pujas As Expressions of 'Urban Folk Culture'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata∗

Modern Asian Studies: page 1 of 39 C Cambridge University Press 2017 doi:10.1017/S0026749X16000913 REVIEW ARTICLE Goddess in the City: Durga pujas of contemporary Kolkata∗ MANAS RAY Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, India Email: [email protected] Tapati Guha-Thakurta, In the Name of the Goddess: The Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata (Primus Books, Delhi, 2015). The goddess can be recognized by her step. Virgil, The Aeneid,I,405. Introduction Durga puja, or the worship of goddess Durga, is the single most important festival in Bengal’s rich and diverse religious calendar. It is not just that her temples are strewn all over this part of the world. In fact, goddess Kali, with whom she shares a complementary history, is easily more popular in this regard. But as a one-off festivity, Durga puja outstrips anything that happens in Bengali life in terms of pomp, glamour, and popularity. And with huge diasporic populations spread across the world, she is now also a squarely international phenomenon, with her puja being celebrated wherever there are even a score or so of Hindu Bengali families in one place. This is one Bengali festival that has people participating across religions and languages. In that ∗ Acknowledgements: Apart from the two anonymous reviewers who made meticulous suggestions, I would like to thank the following: Sandhya Devesan Nambiar, Richa Gupta, Piya Srinivasan, Kamalika Mukherjee, Ian Hunter, John Frow, Peter Fitzpatrick, Sumanta Banjerjee, Uday Kumar, Regina Ganter, and Sharmila Ray. Thanks are also due to Friso Maecker, director, and Sharmistha Sarkar, programme officer, of the Goethe Institute/Max Mueller Bhavan, Kolkata, for arranging a conversation on the book between Tapati Guha-Thakurta and myself in September 2015. -

IROWA DIRECTORY 2018 Indian Oil Retired Officers Welfare Association

IROWA DIRECTORY 2018 Indian Oil Retired Officers Welfare Association The Future of Energy? The Choice is Natural! Natural Gas is emerging as the fuel of the 21 century, steadily replacing liquid fuels and coal due to its low ecological footprint and inherent advantages for all user segments; Industries-Transport- Households. Indian Oil Corporation Limited (IndianOil), India's downstream petroleum major, proactively took up marketing of natural gas over a decade ago through its joint venture, Petronet LNG Ltd., that has set up two LNG (Liquefied Natural Gas) import terminals at Dahej and Kochi on the west coast of India. Over the years, the Corporation has rapidly expanded its customer base of gas-users by leveraging its proven marketing expertise in liquid fuels and its countrywide reach. Its innovative 'LNG at the Doorstep' initiative is highly popular with bulk consumers located away from pipelines. IndianOil is now importing more quantities of LNG directly to meet the increasing domestic demand. A 5-MMTPA LNG terminal being set up by IndianOil at Kamarajar Port in Ennore has achieved an overall progress of over 90% till now and would be commissioned by the end of 2018. The Corporation is currently operating city gas distribution (CGD) networks, offering compressed natural gas (CNG) for vehicles and piped natural gas (PNG) for households, in nine Geographical Areas (GA) through two joint ventures. Considering the growth potential in gas business, the Company is aggressively taking part in the various bidding rounds for Gas. IndianOil is also adding CNG as green auto-fuel at its 27,000+ fuel stations across India and is also collaborating with fleet owners and automobile manufacturers to promote the use of LNG as transportation fuel. -

Durga Puja Pandals of Kolkata 2016: the Heritage and the Design

International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, Vol. 8, No. 6, June 2018 Durga Puja Pandals of Kolkata 2016: The Heritage and the Design Tripti Singh There is one theme all over which is to worship mother Abstract—Durga Puja [1] also known as Sharadotsav or nature, through modern traditions have sub-themes. These Durgotsava is an annual festival of West Bengal, India, where sub-themes which are different in each Durga Puja pandals artists, designers and architects use innovative themes to throughout the region. They display theme based artistically decorate unique pandals to impress the visitors each year. It depicted sculptures of an idol of Maa Durga [7]. Puja involves planning and tedious hard work to give it virtual form. It was interesting that Kolkata (formerly Calcutta) is the organisers put a lot of time, thinking and a lot of means on capital of India's West Bengal state has an area of 185 km², these themed pandals. These pandals are works of art in more than 4500 pandals [2] were erected in that area during their own right. The creativity stun, attract attention and the five - day of Durga Puja was from October 7 until October praise of viewers.The artistic achievements are to attract the 11, 2016. visitor. There are also token of appreciation through prizes Each year there are unique themes which comprise art and of a different category to be won by the designer. design techniques at the single place, time and event. Pandals are distinctive from each other, also they deliver a meaningful message to the society. -

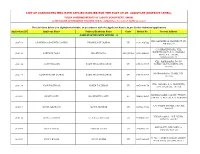

List of Candidates Called for Preliminary Examination for Direct Recruitment of Grade-Iii Officers in Assam Judicial Service

LIST OF CANDIDATES CALLED FOR PRELIMINARY EXAMINATION FOR DIRECT RECRUITMENT OF GRADE-III OFFICERS IN ASSAM JUDICIAL SERVICE. Sl No Name of the Category Roll No Present Address Candidate 1 2 3 4 5 1 A.M. MUKHTAR AHMED General 0001 C/O Imran Hussain (S.I. of Ploice), Convoy Road, Near Radio Station, P.O.- CHOUDHURY Boiragimath, Dist.- Dibrugarh, Pin-786003, Assam 2 AAM MOK KHENLOUNG ST 0002 Tipam Phakey Village, P.O.- Tipam(Joypur), Dist.- Dibrugarh(Assam), Pin- 786614 3 ABBAS ALI DEWAN General 0003 Vill: Dewrikuchi, P.O.:-Sonkuchi, P.S.& Dist.:- Barpeta, Assam, Pin-781314 4 ABDIDAR HUSSAIN OBC 0004 C/O Abdul Motin, Moirabari Sr. Madrassa, Vill, PO & PS-Moirabari, Dist-Morigaon SIDDIQUEE (Assam), Pin-782126 5 ABDUL ASAD REZAUL General 0005 C/O Pradip Sarkar, Debdaru Path, H/No.19, Dispur, Ghy-6. KARIM 6 ABDUL AZIM BARBHUIYA General 0006 Vill-Borbond Part-III, PO-Baliura, PS & Dist-Hailakandi (Assam) 7 ABDUL AZIZ General 0007 Vill. Piradhara Part - I, P.O. Piradhara, Dist. Bongaigaon, Assam, Pin - 783384. 8 ABDUL AZIZ General 0008 ISLAMPUR, RANGIA,WARD NO2, P.O.-RANGIA, DIST.- KAMRUP, PIN-781365 9 ABDUL BARIK General 0009 F. Ali Ahmed Nagar, Panjabari, Road, Sewali Path, Bye Lane - 5, House No.10, Guwahati - 781037. 10 ABDUL BATEN ACONDA General 0010 Vill: Chamaria Pam, P.O. Mahtoli, P.S. Boko, Dist. Kamrup(R), Assam, Pin:-781136 11 ABDUL BATEN ACONDA General 0011 Vill: Pub- Mahachara, P.O. & P.S. -Kachumara, Dist. Barpeta, Assam, Pin. 781127 12 ABDUL BATEN SK. General 0012 Vill-Char-Katdanga Pt-I, PO-Mohurirchar, PS-South Salmara, Dist-Dhubri (Assam) 13 ABDUL GAFFAR General 0013 C/O AKHTAR PARVEZ, ADVOCATE, HOUSE NO. -

Full Text: DOI

Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities (ISSN 0975-2935) Indexed by Web of Science, Scopus, DOAJ, ERIHPLUS Themed Issue on “India and Travel Narratives” (Vol. 12, No. 3, 2020) Guest-edited by: Ms. Somdatta Mandal, PhD Full Text: http://rupkatha.com/V12/n3/v12n332.pdf DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v12n3.32 Representing Kolkata : A Study of ‘Gaze’ Construction in Amit Chaudhuri’s Calcutta: Two Years in the City and Bishwanath Ghosh’s Longing Belonging: An Outsider at Home in Calcutta Saurabh Sarmadhikari Assistant Professor, Department of English, Gangarampur College, Dakshin Dinajpur, West Bengal. ORCID: 0000-0002-8577-4878. Email: [email protected] Abstract Indian travel writings in English exclusively on Kolkata have been rare even though tourist guidebooks such as the Lonely Planet have dedicated sections on the city. In such a scenario, Amit Chaudhuri’s Calcutta: Two Years in the City (2016) and Bishwanath Ghosh’s Longing Belonging: An Outsider at Home in Calcutta (2014) stand out as exceptions. Both these narratives, written by probashi (expatriate) Bengalis, represent Kolkata though a bifocal lens. On the one hand, their travels are a journey towards rediscovering their Bengali roots and on the other, their representation/construction of the city of Kolkata is as hard-boiled as any seasoned traveller. The contention of this paper is that both Chaudhuri and Ghosh foreground certain selected/pre- determined signifiers that are common to Kolkata for the purpose of their representation which are instrumental in constructing the ‘gaze’ of their readers towards the city. This process of ‘gaze’ construction is studied by applying John Urry and Jonas Larsen’s conceptualization of the ‘tourist gaze’. -

Indian Water Works Association 47Th IWWA Annual Conven On, Kolkata

ENTI NV ON O 2 0 C 1 L 5 A , K U Indian Water Works O N L N K A A h T t A 7 Association 4 47th Annual Convention Kolkata 30th, 31st Jan & 1st Feb, 2015 Theme: ‘Sustainable Technology Soluons for Water Management’ Venue: Science City J.B.S Haldane Avenue Kolkata ‐ 700046, (West Bengal) Convention Hosted By IWWA Kolkata Centre INDIAN WATER WORKS ASSOCIATION 47th IWWA ANNUAL CONVENTION, KOLKATA Date : 30th, 31st January & 1st February, 2015 Venue : Science City, J.B.S Haldane Avenue, Kolkata ‐ 700046, West Bengal APPEAL Dear sir, The Indian Water Works Associaon (IWWA) is a voluntary body of professionals concerned and connected with water supply for rural, urban, industrial, agricultural uses and disposal of wastewater. IWWA focuses basically on the enre 'Water Cycle' encompassing the environmental, social, instuonal and financial issues in the area of water supply, wastewater treatment & disposal. IWWA was founded in the year 1968 with headquarters at Mumbai having 32 centers across the country with more than 9000 members from all professions around the world. The Kolkata Centre of IWWA in associaon with Public Health Engineering Department, Govt. of West Bengal along with others is organizing The 47th IWWA Convenon in Kolkata from 30th January to 1st February, 2015 at Science City, J.B.S Haldane Avenue, Kolkata ‐ 700046, West Bengal under the Theme 'Sustainable Technology Soluons for Water Management'. The professionals from all over the country and abroad will parcipate and present their technical papers in the three days convenon. The organizing commiee would like to showcase the Kolkata convenon in a very meaningful manner and make it a grand success and a memorable event to be cherished for a long me. -

Ward No: 034 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Ward No: 034 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID Year No Male Female Total 1 1/6 BAROWARITALA ROAD ABHAY KARMAKAR LT. MARARI KARMAKAR 3 2 5 3 2 2/12A RASHMONI BAZAR ROAD KOL-10 AJAY BHATTACHARJEE LT.ABONI MOHON BHATTACHAR 3 1 4 5 3 122/11/1 B M RD.KOL-10 AJAY DAS LT HARIPADA DAS 4 3 7 6 4 B T RD 47/C B T RD KOL-10 AJOY DAS LT BIJOY DAS 2 1 3 10 5 23 C P RD.KOL-10 AKHILESH SINGH LT SAMBHU SINGH 3 1 4 12 6 CHALPATTI ROAD 23 CHALPATTI ROAD AKSHILESH SINGH LT SAMBHU SINGH 3 1 4 13 7 29A/H/7 C P RD.KOL-10 ALO RANI SAHA LT NARAYAN CH SAHA 0 1 1 14 8 153/8 B M RD.KOL-10 ALOK ROY LT TARINI ROY 2 1 3 16 9 44/B R R L M RD.KOL-85 ALOKA KHAN LT BANOBI KHAN 1 1 2 17 10 131/20 R R L M RD.KOL-85 ALPANA PANJA LT KHUDIRAM PANJA 0 4 4 18 11 JELE PARA 131/20 RAJA RAJENDRA PAL MITRA ROAD ALPANA PANJA KHUDIRAM PANJA 2 2 4 19 12 29/4/A B T RD.KOL-10 AMAL KRISHNA SARKAR LT A K SARKAR 3 1 4 21 13 5/B HEMCHANDRA NASKAR RD AMAL SAHA LATE HARIDAS SAHA 2 4 6 22 14 B M RD 162/H/2 B M RD AMAL SARKAR LT BISTU PADA SARKAR 2 1 3 23 15 9A B M RD AMAR KRISHNA KUNDU NITYANANDA KUNDU 2 2 4 25 16 1/16 B T RD.KOL-10 AMITA DAS LT DILIP DAS 0 1 1 26 17 9A B M RD AMIYA BALA ADHIKARI LATE BALARAM ADHIKARY 0 3 3 27 18 12/H/11 K B LANE.KOL-10 AMULYA BANERJEE LT MANORANJAN BANERJEE 2 1 3 28 19 2/11 R B RD.KOL-10 AMULYA MONDAL LT MAHENDRA MONDAL 0 0 1 29 20 163/3 B M RD ANANDA DAS GURUDAS DAS 3 2 5 30 21 MUCHI PARA 4A/20 RASMANI BAZAR ROAD ANANDA PAL LT GANESH PAL 2 1 3 31 22 10/1/H/2 S K RD.KOL-10 ANIL BARAN CHAKRABORTY LT ABINASH CHAKRABORTY 2 1 3 36 23 27/13 B M ROAD ANIL CHANDRA DAS LT. -

Heritage and the Mritshilpis and Pratimashilpis of Kumartuli

Heritage and the Mritshilpis and Pratimashilpis of Kumartuli Report on a consultative meeting held in Kolkata, West Bengal, 25 November 2018, with proposals for research Samir Kumar Das, Bishnupriya Basak, John Reuben Davies, and Meghna Guhathakurta January 2019 Participants (Alphabetical order) Anita Agnihotri, author of Kalakātāra pratimāśilpīrā (formerly Secretary of Government of India Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, and Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation) Dr Bishnupriya Basak, University of Calcutta Professor Pradip Bose, formerly with Centre for Studies in Social Sciences Calcutta Dr Arnab Das, University of Calcutta Dr Debashish Das, Jadavpur University, Kolkata Professor Samir Kumar Das, University of Calcutta Dr Soujit Das, Government College of Art and Craft, Kolkata Dr John Reuben Davies, University of Glasgow Dr Debdutta Gupta, St Xavier’s College, Kolkata Professor Meghna Guhathakurta, Research Initiatives, Bangladesh, Dhaka Somen Pal (Pratimashilpi from Kumartuli) 3 FOREWORD Kumartuli is a neighbourhood of Kolkata that sits on the east bank of the Hooghly, four kilometres upstream of BBD Bag (Dalhousie Square). The locality is home and workplace to around five hundred artists and artisans, specialists and masters in the art of devotional sculpture in unbaked clay, who fashion the pratimas (deity-icons) for Durga Puja and other Bengali religious festivals. Kumartuli is the heart and focus in West Bengal for pratimashilpa (the metier of making deity-icons). It was founded after the mass migration of Kumbhakars (earthen-pot makers) from Krishnanagar, now in the district of Nadia (sixty-five miles north of Kolkata), to the metropolis and their subsequent colonisation of a vicinity they called the tuli (locality) of the kumar (potters). -

The Gauhati High Court

Gauhati High Court List of candidates who are provisionally allowed to appear in the preliminary examination dated 6-10-2013(Sunday) for direct recruitment to Grade-III of Assam Judicial Service SL. Roll Candidate's name Father's name Gender category(SC/ Correspondence address No. No. ST(P)/ ST(H)/NA) 1 1001 A K MEHBUB KUTUB UDDIN Male NA VILL BERENGA PART I AHMED LASKAR LASKAR PO BERENGA PS SILCHAR DIST CACHAR PIN 788005 2 1002 A M MUKHTAR AZIRUDDIN Male NA Convoy Road AHMED CHOUDHURY Near Radio Station CHOUDHURY P O Boiragimoth P S Dist Dibrugarh Assam 3 1003 A THABA CHANU A JOYBIDYA Female NA ZOO NARENGI ROAD SINGHA BYE LANE NO 5 HOUSE NO 36 PO ZOO ROAD PS GEETANAGAR PIN 781024 4 1004 AASHIKA JAIN NIRANJAN JAIN Female NA CO A K ENTERPRISE VILL AND PO BIJOYNAGAR PS PALASBARI DIST KAMRUP ASSAM 781122 5 1005 ABANINDA Dilip Gogoi Male NA Tiniali bongali gaon Namrup GOGOI P O Parbatpur Dist Dibrugarh Pin 786623 Assam 6 1006 ABDUL AMIL ABDUS SAMAD Male NA NAYAPARA WARD NO IV ABHAYAPURI TARAFDAR TARAFDAR PO ABHAYAPURI PS ABHAYAPURI DIST BONGAIGAON PIN 783384 ASSAM 7 1007 ABDUL BASITH LATE ABDUL Male NA Village and Post Office BARBHUIYA SALAM BARBHUIYA UTTAR KRISHNAPUR PART II SONAI ROAD MLA LANE SILCHAR 788006 CACHAR ASSAM 8 1008 ABDUL FARUK DEWAN ABBASH Male NA VILL RAJABAZAR ALI PO KALITAKUCHI PS HAJO DIST KAMRUP STATE ASSAM PIN 781102 9 1009 ABDUL HANNAN ABDUL MAZID Male NA VILL BANBAHAR KHAN KHAN P O KAYAKUCHI DIST BARPETA P S BARPETA STATE ASSAM PIN 781352 10 1010 ABDUL KARIM SAMSUL HOQUE Male NA CO FARMAN ALI GARIGAON VIDYANAGAR PS -

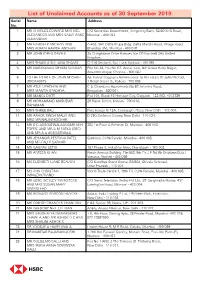

List of Unclaimed Accounts As of 30 September 2019. Serial Name Address No

List of Unclaimed Accounts as of 30 September 2019. Serial Name Address No. 1 MR CHARLES EDWARD MICHAEL C/O Securtiies Department, Hongkong Bank, 52/60 M G Road, ALEXANDER AND MRS SALLY ANNE Mumbai - 400 023 ALEXANDER 2 MR HARISH P ANCHAN AND A-402, Shri Datta Krupa Bldg, Datta Mandir Road, Village Road, MRS ROHINI HARISH ANCHAN Bhandup (W), Mumbai - 400 078. 3 MR JOHN IDRES DAVIES 25 Claughbane Drive Ramsey Isle Of Man Im8 2Ay United Kingdom. 4 MRS SHAKILA SULTANA SHAMS Cl-176 Sector-II, Salt Lake, Kolkata - 700 091. 5 MR NARAYANAN SHYAM SUNDAR Plot No 34, Flat No G2, Annai Illam, 6th Street Balaji Nagar, Alwarthirunagar, Chennai - 600 087. 6 TO THE ESTATE OF JOHN MICHAEL Ajit Kumar Dasgupta Administrator To The Estate Of John Michael, (DECEASED) 1 British Indian St, Kolkata - 700 069. 7 MR ATUL UPADHYA AND C-5, Chandana Apartments No 82, Infantry Road, MRS MAMTA UPADHYA Bengaluru - 560 001. 8 MR MANOJ DUTT Flat 101, Block 45 Heritage City, Gurgaon - 122 002. 4013739 9 MR MOHAMMAD MASUDAR 28 Ripon Street, Kolkata - 700 016. RAHAMAN 10 MRS SHREE BALI Punj House M 13A, Connaught Place, New Delhi - 110 001. 11 MR ASHOK SINGH MALIK AND D-250, Defence Colony, New Delhi - 110 024. MRS MRINALINI KOCHAR 12 MR S D AGBOATWALAANDMR M H 282 1st Floor A Rehman St, Mumbai - 400 003. TOFFIC AND MR A M PATKA (DEC) AND MR A A AGBOATWALA 13 MR JEHANGIR PESTONJI PATEL Gulestan, Cuffe Parade, Mumbai - 400 005. AND MR FALI P SARKARI 14 MR GAURAV SETHI 157 Phase II, Industrial Area, Chandigarh - 160 002. -

Biswa Bangla Sharad Samman 2019, List of Winners

--- ........ ! " # $%&' " ( )*# + , + + - ./ + 0 12/ 1%' 3 4' 56 " 7 #!/ 6' 869 :; < = <>? 6 6' 869 @/ ( A<' 6' 869 , ' 6' 869 - *& 0 - B' " 3 C= - B' 7 DE=E F@ 6 6' $ 6' 869 ' + =/' " G ( < 6' 869 , E 6' 869 - H # 1 @/ 0 +I' *& + 3 , B' ", <= = 6' 869 2L / + K2K2K2 ( .M2L N , = = B' + + ( I;= 6 6' <>? " 6' 86 P/ 6' 869 AO ( <'6 , @/ 6' 869 --- ........ E= 6' 6' ( +4', '+ , 226 Q A= - # 0 A H 6' 869 ARS + =E ' G ( $/ < , =E - 6 # " 0 '= 3- B' 3 T U& 6' = G ;& 869 ( 37 B' # 869 , 3, B' " - D, '= 0 < V' 869 3 I=W:' 7 " B' '= X/26 " # 6' 869 R =P '= Y;' + ( 00 B' " , < ' - @K2 - <= . 56 " 0 /' 869 3 Z%'& 9 7 0, B' 869 [R= 1. .\ B' N X= 869 , /] . ! Q +, B' 6' 869 +I' $ @K2 _ ^^^^ 6# ` + ( [R= B' abc' 6' d@K2 A= 6' \ L )*# + Biswa Bangla Sharad Samman 2019, List of Winners Sl. No CATEGORY SL. No. NAME OF THE PUJO COMMITTEE 1 1 Barisha Club 2 2 Chetla Agrani Club 3 3 Suruchi Sangha 4 4 Kalighat Milan Sangha 5 5 Naktala Udayan Sangha 6 6 Ekdalia Evergreen 7 7 Shribhumi Sporting Club 8 8 Chakraberia Sarbojonin Durgotsab 9 9 Tridhara 10 10 Behala Notundal 11 11 Hindusthan Park Sorbojonin Durgotsab 12 12 Tala Prattay 13 13 Ahiritola Sorbojoninn Durgotsab Samity 14 Serar Sera 14 Kasi Bose Lane Sorbojonin Durgotsab 15 15 Dumdum Tarundol 16 16 95 Pally Club 17 17 Khidirpur 25 Pally 18 18 Thakurpukur State Bank Park Sarbojonin Committee 19 19 Abasar Sarbojonin Durgotsab Committee 20 20 Samajsebi Sangha 21 21 Mudiali Club 22 22 Shib Mandir 23 23 Hatibagan Sarbojonin Durgotsab Committee 24 24 Bakul Bagan Sarbojonin Durgotsab 25 25 Ballygunge Cultural Association 26 26 Baghajatin Tarun Sangha 27 27 41 Pally Club, Haridevpur Biswa Bangla Sharad Samman 2019, List of Winners Sl. -

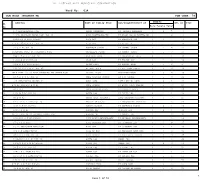

List of Candidates Who Have Applied Earlier for the Post of Jr. Assistant (District Level)

LIST OF CANDIDATES WHO HAVE APPLIED EARLIER FOR THE POST OF JR. ASSISTANT (DISTRICT LEVEL), UNDER COMMISSIONERATE OF LABOUR DEPARTMENT, ASSAM, AS PER EARLIER ADVERTISEMENT PUBLISHED VIDE NO. JANASANYOG/ D/11915/17, DATED 20-12-2017 The List Given below is in Alphabetical Order, in accordance with the Applicant Name ( As per Earlier Submited Application) Application ID Applicant Name Fathers/Husbands Name Caste Mobile No. Present Address NAME STARTING WITH LETTER: - 'A' VILL DAKSHIN MOHANPUR PT VII, 200718 A B MEHBOOB AHMED LASKAR NIYAMUDDIN LASKAR UR 9101308522 PIN 788119 C/O BRAJEN BORA, VILL. KSHETRI GAON, P.O. CHAKALA 206441 AANUPAM BORA BRAJEN BORA OBC/MOBC 9401696850 GHAT, P.S. JAJORI, NAGAON782142 VILL- MAIRAMARA, PO+PS- 200136 AASIF HUSSAIN ZAKIR HUSSAIN LASKAR UR 8753915707 HOWLY, DIST-BARPETA, PIN- 781316 MOIRAMARA PO-HOWLI, PIN- 200137 AASIF HUSSAIN LASKAR ZAKIR HUSSAIN LASKAR UR 8753915707 781316 VILL.-NAPARA, P.O.-HORUPETA, 200138 ABAN TALUKDAR NAREN TALUKDAR UR 9859404178 DIST.-BARPETA, 781318 NARENGI ASEB COLONY, TYPE IV, 203003 ABANI DOLEY KASHINATH DOLEY SC 7664836895 QTR NO. 4, GHY-26, P.O. NARENGI C/O SALMA STORES, GAR ALI, 202015 ABDUL GHAFOOR ABDUL MANNAN UR 8876215529 JORHAT VILL&P.O.&P.S.:- NIZ-DHING, 206442 ABDUL HANNAN LT. ABDUL MOTALIB UR 9706865304 NAGAON-782123 MAYA PATH, BYE LANE 1A, 203004 ABDUL HAYEE FAKHAR UDDIN UR 7002903504 SIXMILE, GHY-22 H. NO. 4, PEER DARGAH, SHARIF, 203005 ABDUL KALAM ABDUL KARIM UR 9435460827 NEAR ASEB, ULUBARI, GHY 7 HATKHOLA BONGALI GAON, CHABUA TATA GATE, LITTLE AGEL 201309 ABDUL KHAN NUR HUSSAIN KHAN UR 9678879562 SCHOOL ROAD, CHABUA, DIST DIBRUGARH 786184 BIRUBARI SHANTI PATH, H NO.