Heritage and the Mritshilpis and Pratimashilpis of Kumartuli

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata∗

Modern Asian Studies: page 1 of 39 C Cambridge University Press 2017 doi:10.1017/S0026749X16000913 REVIEW ARTICLE Goddess in the City: Durga pujas of contemporary Kolkata∗ MANAS RAY Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, India Email: [email protected] Tapati Guha-Thakurta, In the Name of the Goddess: The Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata (Primus Books, Delhi, 2015). The goddess can be recognized by her step. Virgil, The Aeneid,I,405. Introduction Durga puja, or the worship of goddess Durga, is the single most important festival in Bengal’s rich and diverse religious calendar. It is not just that her temples are strewn all over this part of the world. In fact, goddess Kali, with whom she shares a complementary history, is easily more popular in this regard. But as a one-off festivity, Durga puja outstrips anything that happens in Bengali life in terms of pomp, glamour, and popularity. And with huge diasporic populations spread across the world, she is now also a squarely international phenomenon, with her puja being celebrated wherever there are even a score or so of Hindu Bengali families in one place. This is one Bengali festival that has people participating across religions and languages. In that ∗ Acknowledgements: Apart from the two anonymous reviewers who made meticulous suggestions, I would like to thank the following: Sandhya Devesan Nambiar, Richa Gupta, Piya Srinivasan, Kamalika Mukherjee, Ian Hunter, John Frow, Peter Fitzpatrick, Sumanta Banjerjee, Uday Kumar, Regina Ganter, and Sharmila Ray. Thanks are also due to Friso Maecker, director, and Sharmistha Sarkar, programme officer, of the Goethe Institute/Max Mueller Bhavan, Kolkata, for arranging a conversation on the book between Tapati Guha-Thakurta and myself in September 2015. -

In Conversation with Sanjukta Dasgupta

In Conversation with Sanjukta Dasgupta Jaydeep Sarangi and Antara Ghatak Sanjukta Dasgupta, Professor and Former Head, Dept of English and Ex- Dean, Faculty of Arts, Calcutta University, teaches English and American literature along with New Literatures in English. She is a poet, critic and translator, and her articles, poems, short stories and translations have been published in journals of distinction in India and abroad. Her inner sphere overlaps the outer on the speculative and the shadowy. There is a sublime inwardness in her poems. Her recent signal books include Snapshots, Dilemma, First Language, More Light, and Lakshmi Unbound. She co-authored Radical Rabindranath: Nation, Family, Gender: Post-colonial Readings of Tagore’s Fiction and Film, and she is the Managing Editor of Families: A Journal of Representations. She has received many grants and awards, including Fulbright fellowships and residencies and an Australia India Council Fellowship. Now she is the Convener, English Board, Shaitya Akademi. Professor Dasgupta has visited Nepal and Bangladesh as a member of the SAARC Writers Delegation, and has served as a co-judge and Chairperson for the Commonwealth Writers Prize (Eurasia region). She has visited Melbourne and Malta to serve on the pan- Commonwealth jury panel. She is now an e-member of the advisory committee of the Commonwealth Writers Prize, UK. She is Visiting Professor, Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland, and she is the President of the Executive Committee, Intercultural Poetry and Performance Library in Kolkata. The interview was conducted via email in December 2018. Q: When did you start writing poems and short stories? In Conversation with Sanjukta Dasgupta. -

People Without History

People Without History Seabrook T02250 00 pre 1 24/12/2010 10:45 Seabrook T02250 00 pre 2 24/12/2010 10:45 People Without History India’s Muslim Ghettos Jeremy Seabrook and Imran Ahmed Siddiqui Seabrook T02250 00 pre 3 24/12/2010 10:45 First published 2011 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010 www.plutobooks.com Distributed in the United States of America exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010 Copyright © Jeremy Seabrook and Imran Ahmed Siddiqui 2011 The right of Jeremy Seabrook and Imran Ahmed Siddiqui to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3114 0 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3113 3 Paperback Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data applied for This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Designed and produced for Pluto Press by Chase Publishing Services Ltd, 33 Livonia Road, Sidmouth, EX10 9JB, England Typeset from disk by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Simultaneously printed digitally by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham, UK and Edwards Bros in the USA Seabrook T02250 00 pre 4 24/12/2010 10:45 Contents Acknowledgements vi Introduction 1 1. -

Studies in the History of Prostitution in North Bengal : Colonial and Post - Colonial Perspective

STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF PROSTITUTION IN NORTH BENGAL : COLONIAL AND POST - COLONIAL PERSPECTIVE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY TAMALI MUSTAFI Under the Supervision of PROFESSOR ANITA BAGCHI DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL RAJA RAMMOHUNPUR DARJEELING, PIN - 734013 WEST BENGAL SEPTEMBER, 2016 DECLARATION I declare that the thesis entitled ‘STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF PROSTITUTION IN NORTH BENGAL : COLONIAL AND POST - COLONIAL PERSPECTIVE’ has been prepared by me under the guidance of Professor Anita Bagchi, Department of History, University of North Bengal. No part of this thesis has formed the basis for the award of any degree or fellowship previously. Date: 19.09.2016 Department of History University of North Bengal Raja Rammohunpur Darjeeling, Pin - 734013 West Bengal CERTIFICATE I certify that Tamali Mustafi has prepared the thesis entitled ‘STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF PROSTITUTION IN NORTH BENGAL : COLONIAL AND POST – COLONIAL PERSPECTIVE’, of the award of Ph.D. degree of the University of North Bengal, under my guidance. She has carried out the work at the Department of History, University of North Bengal. Date: 19.09.2016 Department of History University of North Bengal Raja Rammohunpur Darjeeling, Pin - 734013 West Bengal ABSTRACT Prostitution is the most primitive practice in every society and nobody can deny this established truth. Recently women history is being given importance. Writing the history of prostitution in Bengal had already been started. But the trend of those writings does not make any interest to cover the northern part of Bengal which is popularly called Uttarbanga i.e. -

IROWA DIRECTORY 2018 Indian Oil Retired Officers Welfare Association

IROWA DIRECTORY 2018 Indian Oil Retired Officers Welfare Association The Future of Energy? The Choice is Natural! Natural Gas is emerging as the fuel of the 21 century, steadily replacing liquid fuels and coal due to its low ecological footprint and inherent advantages for all user segments; Industries-Transport- Households. Indian Oil Corporation Limited (IndianOil), India's downstream petroleum major, proactively took up marketing of natural gas over a decade ago through its joint venture, Petronet LNG Ltd., that has set up two LNG (Liquefied Natural Gas) import terminals at Dahej and Kochi on the west coast of India. Over the years, the Corporation has rapidly expanded its customer base of gas-users by leveraging its proven marketing expertise in liquid fuels and its countrywide reach. Its innovative 'LNG at the Doorstep' initiative is highly popular with bulk consumers located away from pipelines. IndianOil is now importing more quantities of LNG directly to meet the increasing domestic demand. A 5-MMTPA LNG terminal being set up by IndianOil at Kamarajar Port in Ennore has achieved an overall progress of over 90% till now and would be commissioned by the end of 2018. The Corporation is currently operating city gas distribution (CGD) networks, offering compressed natural gas (CNG) for vehicles and piped natural gas (PNG) for households, in nine Geographical Areas (GA) through two joint ventures. Considering the growth potential in gas business, the Company is aggressively taking part in the various bidding rounds for Gas. IndianOil is also adding CNG as green auto-fuel at its 27,000+ fuel stations across India and is also collaborating with fleet owners and automobile manufacturers to promote the use of LNG as transportation fuel. -

Durga Puja Pandals of Kolkata 2016: the Heritage and the Design

International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, Vol. 8, No. 6, June 2018 Durga Puja Pandals of Kolkata 2016: The Heritage and the Design Tripti Singh There is one theme all over which is to worship mother Abstract—Durga Puja [1] also known as Sharadotsav or nature, through modern traditions have sub-themes. These Durgotsava is an annual festival of West Bengal, India, where sub-themes which are different in each Durga Puja pandals artists, designers and architects use innovative themes to throughout the region. They display theme based artistically decorate unique pandals to impress the visitors each year. It depicted sculptures of an idol of Maa Durga [7]. Puja involves planning and tedious hard work to give it virtual form. It was interesting that Kolkata (formerly Calcutta) is the organisers put a lot of time, thinking and a lot of means on capital of India's West Bengal state has an area of 185 km², these themed pandals. These pandals are works of art in more than 4500 pandals [2] were erected in that area during their own right. The creativity stun, attract attention and the five - day of Durga Puja was from October 7 until October praise of viewers.The artistic achievements are to attract the 11, 2016. visitor. There are also token of appreciation through prizes Each year there are unique themes which comprise art and of a different category to be won by the designer. design techniques at the single place, time and event. Pandals are distinctive from each other, also they deliver a meaningful message to the society. -

List of Candidates Called for Preliminary Examination for Direct Recruitment of Grade-Iii Officers in Assam Judicial Service

LIST OF CANDIDATES CALLED FOR PRELIMINARY EXAMINATION FOR DIRECT RECRUITMENT OF GRADE-III OFFICERS IN ASSAM JUDICIAL SERVICE. Sl No Name of the Category Roll No Present Address Candidate 1 2 3 4 5 1 A.M. MUKHTAR AHMED General 0001 C/O Imran Hussain (S.I. of Ploice), Convoy Road, Near Radio Station, P.O.- CHOUDHURY Boiragimath, Dist.- Dibrugarh, Pin-786003, Assam 2 AAM MOK KHENLOUNG ST 0002 Tipam Phakey Village, P.O.- Tipam(Joypur), Dist.- Dibrugarh(Assam), Pin- 786614 3 ABBAS ALI DEWAN General 0003 Vill: Dewrikuchi, P.O.:-Sonkuchi, P.S.& Dist.:- Barpeta, Assam, Pin-781314 4 ABDIDAR HUSSAIN OBC 0004 C/O Abdul Motin, Moirabari Sr. Madrassa, Vill, PO & PS-Moirabari, Dist-Morigaon SIDDIQUEE (Assam), Pin-782126 5 ABDUL ASAD REZAUL General 0005 C/O Pradip Sarkar, Debdaru Path, H/No.19, Dispur, Ghy-6. KARIM 6 ABDUL AZIM BARBHUIYA General 0006 Vill-Borbond Part-III, PO-Baliura, PS & Dist-Hailakandi (Assam) 7 ABDUL AZIZ General 0007 Vill. Piradhara Part - I, P.O. Piradhara, Dist. Bongaigaon, Assam, Pin - 783384. 8 ABDUL AZIZ General 0008 ISLAMPUR, RANGIA,WARD NO2, P.O.-RANGIA, DIST.- KAMRUP, PIN-781365 9 ABDUL BARIK General 0009 F. Ali Ahmed Nagar, Panjabari, Road, Sewali Path, Bye Lane - 5, House No.10, Guwahati - 781037. 10 ABDUL BATEN ACONDA General 0010 Vill: Chamaria Pam, P.O. Mahtoli, P.S. Boko, Dist. Kamrup(R), Assam, Pin:-781136 11 ABDUL BATEN ACONDA General 0011 Vill: Pub- Mahachara, P.O. & P.S. -Kachumara, Dist. Barpeta, Assam, Pin. 781127 12 ABDUL BATEN SK. General 0012 Vill-Char-Katdanga Pt-I, PO-Mohurirchar, PS-South Salmara, Dist-Dhubri (Assam) 13 ABDUL GAFFAR General 0013 C/O AKHTAR PARVEZ, ADVOCATE, HOUSE NO. -

Kolkata the Soul of the City

KOLKATA THE SOUL OF THE CITY Miriam Westin March 31, 2014 TUL 540 Project 2 Dr. Viv Grigg “Calcutta has absorbed all the vicissitudes that history and geography have thrown at i her, and managed to retain her dignity.” “Then I will sprinkle clean water on you, and you shall be clean; I will cleanse you from all your filthiness and from all your idols. I will give you a new heart and put a new spirit within you; I will take the heart of stone out of your flesh and give you a heart of flesh. I will put My Spirit within you and cause you to walk in My statutes, and you will keep My judgments and do them...” INTRODUCTION ‘Thus says the Lord God: “On the day that I cleanse you The city of Kolkata is known internationally for her physical from all your iniquities, I will also enable you to dwell in realities, aesthetics and history of exploitation. Yet the cities, and the ruins shall be rebuilt. The desolate simultaneously, she is the cultural capitol of India and is land shall be tilled instead of lying desolate in the sight known as “The City of Joy.” What do these paradoxical realities tell us about her soul? What, if anything, does of all who pass by. So they will say, ‘This land that was Kolkata tell us about her Creator? desolate has become like the garden of Eden; and the wasted, desolate, and ruined cities are now fortified and Through a survey of Kolkata's past and present realities, I will inhabited.’ Then the nations which are left all around seek to articulate some aspects of Kolkata's soul to you shall know that I, the Lord, have rebuilt the ruined understand where she aligns with and strays from from the places and planted what was desolate. -

Full Text: DOI

Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities (ISSN 0975-2935) Indexed by Web of Science, Scopus, DOAJ, ERIHPLUS Themed Issue on “India and Travel Narratives” (Vol. 12, No. 3, 2020) Guest-edited by: Ms. Somdatta Mandal, PhD Full Text: http://rupkatha.com/V12/n3/v12n332.pdf DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v12n3.32 Representing Kolkata : A Study of ‘Gaze’ Construction in Amit Chaudhuri’s Calcutta: Two Years in the City and Bishwanath Ghosh’s Longing Belonging: An Outsider at Home in Calcutta Saurabh Sarmadhikari Assistant Professor, Department of English, Gangarampur College, Dakshin Dinajpur, West Bengal. ORCID: 0000-0002-8577-4878. Email: [email protected] Abstract Indian travel writings in English exclusively on Kolkata have been rare even though tourist guidebooks such as the Lonely Planet have dedicated sections on the city. In such a scenario, Amit Chaudhuri’s Calcutta: Two Years in the City (2016) and Bishwanath Ghosh’s Longing Belonging: An Outsider at Home in Calcutta (2014) stand out as exceptions. Both these narratives, written by probashi (expatriate) Bengalis, represent Kolkata though a bifocal lens. On the one hand, their travels are a journey towards rediscovering their Bengali roots and on the other, their representation/construction of the city of Kolkata is as hard-boiled as any seasoned traveller. The contention of this paper is that both Chaudhuri and Ghosh foreground certain selected/pre- determined signifiers that are common to Kolkata for the purpose of their representation which are instrumental in constructing the ‘gaze’ of their readers towards the city. This process of ‘gaze’ construction is studied by applying John Urry and Jonas Larsen’s conceptualization of the ‘tourist gaze’. -

Indian Water Works Association 47Th IWWA Annual Conven On, Kolkata

ENTI NV ON O 2 0 C 1 L 5 A , K U Indian Water Works O N L N K A A h T t A 7 Association 4 47th Annual Convention Kolkata 30th, 31st Jan & 1st Feb, 2015 Theme: ‘Sustainable Technology Soluons for Water Management’ Venue: Science City J.B.S Haldane Avenue Kolkata ‐ 700046, (West Bengal) Convention Hosted By IWWA Kolkata Centre INDIAN WATER WORKS ASSOCIATION 47th IWWA ANNUAL CONVENTION, KOLKATA Date : 30th, 31st January & 1st February, 2015 Venue : Science City, J.B.S Haldane Avenue, Kolkata ‐ 700046, West Bengal APPEAL Dear sir, The Indian Water Works Associaon (IWWA) is a voluntary body of professionals concerned and connected with water supply for rural, urban, industrial, agricultural uses and disposal of wastewater. IWWA focuses basically on the enre 'Water Cycle' encompassing the environmental, social, instuonal and financial issues in the area of water supply, wastewater treatment & disposal. IWWA was founded in the year 1968 with headquarters at Mumbai having 32 centers across the country with more than 9000 members from all professions around the world. The Kolkata Centre of IWWA in associaon with Public Health Engineering Department, Govt. of West Bengal along with others is organizing The 47th IWWA Convenon in Kolkata from 30th January to 1st February, 2015 at Science City, J.B.S Haldane Avenue, Kolkata ‐ 700046, West Bengal under the Theme 'Sustainable Technology Soluons for Water Management'. The professionals from all over the country and abroad will parcipate and present their technical papers in the three days convenon. The organizing commiee would like to showcase the Kolkata convenon in a very meaningful manner and make it a grand success and a memorable event to be cherished for a long me. -

Ward No: 034 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79

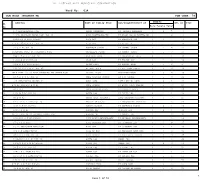

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Ward No: 034 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID Year No Male Female Total 1 1/6 BAROWARITALA ROAD ABHAY KARMAKAR LT. MARARI KARMAKAR 3 2 5 3 2 2/12A RASHMONI BAZAR ROAD KOL-10 AJAY BHATTACHARJEE LT.ABONI MOHON BHATTACHAR 3 1 4 5 3 122/11/1 B M RD.KOL-10 AJAY DAS LT HARIPADA DAS 4 3 7 6 4 B T RD 47/C B T RD KOL-10 AJOY DAS LT BIJOY DAS 2 1 3 10 5 23 C P RD.KOL-10 AKHILESH SINGH LT SAMBHU SINGH 3 1 4 12 6 CHALPATTI ROAD 23 CHALPATTI ROAD AKSHILESH SINGH LT SAMBHU SINGH 3 1 4 13 7 29A/H/7 C P RD.KOL-10 ALO RANI SAHA LT NARAYAN CH SAHA 0 1 1 14 8 153/8 B M RD.KOL-10 ALOK ROY LT TARINI ROY 2 1 3 16 9 44/B R R L M RD.KOL-85 ALOKA KHAN LT BANOBI KHAN 1 1 2 17 10 131/20 R R L M RD.KOL-85 ALPANA PANJA LT KHUDIRAM PANJA 0 4 4 18 11 JELE PARA 131/20 RAJA RAJENDRA PAL MITRA ROAD ALPANA PANJA KHUDIRAM PANJA 2 2 4 19 12 29/4/A B T RD.KOL-10 AMAL KRISHNA SARKAR LT A K SARKAR 3 1 4 21 13 5/B HEMCHANDRA NASKAR RD AMAL SAHA LATE HARIDAS SAHA 2 4 6 22 14 B M RD 162/H/2 B M RD AMAL SARKAR LT BISTU PADA SARKAR 2 1 3 23 15 9A B M RD AMAR KRISHNA KUNDU NITYANANDA KUNDU 2 2 4 25 16 1/16 B T RD.KOL-10 AMITA DAS LT DILIP DAS 0 1 1 26 17 9A B M RD AMIYA BALA ADHIKARI LATE BALARAM ADHIKARY 0 3 3 27 18 12/H/11 K B LANE.KOL-10 AMULYA BANERJEE LT MANORANJAN BANERJEE 2 1 3 28 19 2/11 R B RD.KOL-10 AMULYA MONDAL LT MAHENDRA MONDAL 0 0 1 29 20 163/3 B M RD ANANDA DAS GURUDAS DAS 3 2 5 30 21 MUCHI PARA 4A/20 RASMANI BAZAR ROAD ANANDA PAL LT GANESH PAL 2 1 3 31 22 10/1/H/2 S K RD.KOL-10 ANIL BARAN CHAKRABORTY LT ABINASH CHAKRABORTY 2 1 3 36 23 27/13 B M ROAD ANIL CHANDRA DAS LT. -

Annual Report 17-18 Full Chap Final Tracing.Pmd

VISVA-BHARATI Annual Report 2017-2018 Santiniketan 2018 YATRA VISVAM BHAVATYEKANIDAM (Where the World makes its home in a single nest) “ Visva-Bharati represents India where she has her wealth of mind which is for all. Visva-Bharati acknowledges India's obligation to offer to others the hospitality of her best culture and India's right to accept from others their best ” -Rabindranath Tagore Dee®ee³e& MeebefleefveJesÀleve - 731235 Þeer vejsbê ceesoer efkeMkeYeejleer SANTINIKETAN - 731235 efpe.keerjYetce, heefM®ece yebieeue, Yeejle ACHARYA (CHANCELLOR) VISVA-BHARATI DIST. BIRBHUM, WEST BENGAL, INDIA SHRI NARENDRA MODI (Established by the Parliament of India under heÀesve Tel: +91-3463-262 451/261 531 Visva-Bharati Act XXIX of 1951 hewÀJeÌme Fax: +91-3463-262 672 Ghee®ee³e& Vide Notification No. : 40-5/50 G.3 Dt. 14 May, 1951) F&-cesue E-mail : [email protected] Òees. meyegpeJeÀefue mesve Website: www.visva-bharati.ac.in UPACHARYA (VICE-CHANCELLOR) (Offig.) mebmLeeheJeÀ PROF. SABUJKOLI SEN jkeervêveeLe þeJegÀj FOUNDED BY RABINDRANATH TAGORE FOREWORD meb./No._________________ efoveebJeÀ/Date._________________ For Rabindranath Tagore, the University was the most vibrant part of a nation’s cultural and educational life. In his desire to fashion a holistic self that was culturally, ecologically and ethically enriched, he saw Visva-Bharati as a utopia of the cross cultural encounter. During the course of the last year, the Visva-Bharati fraternity has been relentlessly pursuing this dream. The recent convocation, where the Chancellor Shri Narendra Modi graced the occasion has energized the Univer- sity community, especially because this was the Acharya’s visit after 10 years.