Communications in Observations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Martian Crater Morphology

ANALYSIS OF THE DEPTH-DIAMETER RELATIONSHIP OF MARTIAN CRATERS A Capstone Experience Thesis Presented by Jared Howenstine Completion Date: May 2006 Approved By: Professor M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Professor Christopher Condit, Geology Professor Judith Young, Astronomy Abstract Title: Analysis of the Depth-Diameter Relationship of Martian Craters Author: Jared Howenstine, Astronomy Approved By: Judith Young, Astronomy Approved By: M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Approved By: Christopher Condit, Geology CE Type: Departmental Honors Project Using a gridded version of maritan topography with the computer program Gridview, this project studied the depth-diameter relationship of martian impact craters. The work encompasses 361 profiles of impacts with diameters larger than 15 kilometers and is a continuation of work that was started at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas under the guidance of Dr. Walter S. Keifer. Using the most ‘pristine,’ or deepest craters in the data a depth-diameter relationship was determined: d = 0.610D 0.327 , where d is the depth of the crater and D is the diameter of the crater, both in kilometers. This relationship can then be used to estimate the theoretical depth of any impact radius, and therefore can be used to estimate the pristine shape of the crater. With a depth-diameter ratio for a particular crater, the measured depth can then be compared to this theoretical value and an estimate of the amount of material within the crater, or fill, can then be calculated. The data includes 140 named impact craters, 3 basins, and 218 other impacts. The named data encompasses all named impact structures of greater than 100 kilometers in diameter. -

The Comet's Tale

THE COMET’S TALE Journal of the Comet Section of the British Astronomical Association Number 33, 2014 January Not the Comet of the Century 2013 R1 (Lovejoy) imaged by Damian Peach on 2013 December 24 using 106mm F5. STL-11k. LRGB. L: 7x2mins. RGB: 1x2mins. Today’s images of bright binocular comets rival drawings of Great Comets of the nineteenth century. Rather predictably the expected comet of the century Contents failed to materialise, however several of the other comets mentioned in the last issue, together with the Comet Section contacts 2 additional surprise shown above, put on good From the Director 2 appearances. 2011 L4 (PanSTARRS), 2012 F6 From the Secretary 3 (Lemmon), 2012 S1 (ISON) and 2013 R1 (Lovejoy) all Tales from the past 5 th became brighter than 6 magnitude and 2P/Encke, 2012 RAS meeting report 6 K5 (LINEAR), 2012 L2 (LINEAR), 2012 T5 (Bressi), Comet Section meeting report 9 2012 V2 (LINEAR), 2012 X1 (LINEAR), and 2013 V3 SPA meeting - Rob McNaught 13 (Nevski) were all binocular objects. Whether 2014 will Professional tales 14 bring such riches remains to be seen, but three comets The Legacy of Comet Hunters 16 are predicted to come within binocular range and we Project Alcock update 21 can hope for some new discoveries. We should get Review of observations 23 some spectacular close-up images of 67P/Churyumov- Prospects for 2014 44 Gerasimenko from the Rosetta spacecraft. BAA COMET SECTION NEWSLETTER 2 THE COMET’S TALE Comet Section contacts Director: Jonathan Shanklin, 11 City Road, CAMBRIDGE. CB1 1DP England. Phone: (+44) (0)1223 571250 (H) or (+44) (0)1223 221482 (W) Fax: (+44) (0)1223 221279 (W) E-Mail: [email protected] or [email protected] WWW page : http://www.ast.cam.ac.uk/~jds/ Assistant Director (Observations): Guy Hurst, 16 Westminster Close, Kempshott Rise, BASINGSTOKE, Hampshire. -

812 Ta Ta Basalt Depletion, 820474 Melanesian Basin, 610705, 610707

812 Ta T Ta 910437, 920026, 920117, 920265, 920291 Guaymas Basin, 650644 basalt Panama, Pacific Ocean, 950217 laumontite, 670551 depletion, 820474 pumice, source, 850821 mineralogy Melanesian Basin, 610705, 610707 Volcanic rocks, petrography, alkalic Mariana Islands, 600458 Mid-Atlantic Ridge, 820442, 820445, 820446 island, 200691 Mariana Trench, 600458 midocean ridge, 820396, 820417, 820449, Taif, Saudi Arabia, Red Sea, geology, 230813 Mariana Trough, 600457 820450 Tairyo Formation, 061289 minerals, chemical composition, 600461 hygromagmaphile element, 820460, 820461, Taito Fracture Zone, 870740 Panama Basin, sediments, 690386, 690392 820462, 820464, 820467, 820468 Nankai Trough, heat flow, 870740 Patton Escarpment, petrography, 630687, fractionation, absence, 820460 Taiwan, 061289, 660661, 780578, 840767 630701 nonfractionating pairs, 820467 basin genesis, 310874 Shatskiy Plateau S, 200683 trace elements, 660732 Ryukyu Islands, 310863 temperature, 670551 Goban Spur, 800944 Philippine Basin, genesis, 310863 X-ray diffraction analysis result, 920492 see also tantalum Philippine Sea, Paleogene-Neogene, 310837 Tallahatta Formation, 950365, 950369, 950370 Ta/Hf ratio Philippines Talme Yafe borehole, Mediterranean Sea E, basalt, 820474, 820475 genesis, 310874 history, 42B1202 hygromagmaphile element, 820464, 820465 plate, 600928 Talparo Formation, 040599 Ta/La ratio planktonic foraminiferal biostratigraphy, Tamabra limestone, talus, 770397, 770404 hygromagmaphile element, 820645 310679 Tamatave, Rio Grande Rise N, regional trace elements, -

Edison Pettit Papers: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf9q2nb3w2 No online items Edison Pettit Papers: Finding Aid Processed by Ronald S. Brashear in March 1998. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 1998 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Edison Pettit Papers: Finding Aid mssPettit papers 1 Overview of the Collection Title: Edison Pettit Papers Dates (inclusive): 1920-1969 Collection Number: mssPettit papers Creator: Pettit, Edison, 1889-1962. Extent: 6 boxes (3,100 pieces) Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains the papers of astronomer Edison Pettit (1889-1962), who was on the staff of the Mount Wilson and Palomar Observatories. The correspondence is chiefly with other astronomers in the United States and deals with astronomy in general including Pettit's work at Mount Wilson, telescopes, and ultraviolet light research. The rest of the collection is made up of manuscripts, notes, notebooks and printed items. Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher. -

Yesteryears:Apr 27, 1993 Vol 22 No 2

Section of tfie Salem 1\&ws L toni t I sco e firm as John Mellish was self taught i:nventor, discovered 5 comets By Dale Shaffer inadequate, so he bought a He notified the Washburn OHN EDWARD MELLISH, two-inch r_efractor telescope for Observatory in Madison, and a builder of astronomical $16. It dehghted him by show astronomers there confirmed !lescopes, lived in Leetonia ing him many new stars. that he had sighted a new from 1916 to the mid-1920s. His During these early years he cornet. business was in the front and was reading every book and Another observer, however, second story room of his home article on astronomy he could had also seen the comet, so in the east end. It was unlike get his hands on. Then he Mellish had to share the dis anything of the kind in Colum began reading a book on how covery. The comet was named biana County. In fact, his was to make telescopes and "1907 II Grigg-Mellish." In the one of only six such telescope decided to make o~e for fall of that year Mellish spotted making businesses in the himself. another new cornet, and this United States. He sent to Chicago for two time his name alone was given One of his large telescopes glass disks six inches in diame to it. was mounted on a tripod in his ~er and s:pent the winter grind- Mellish was now in touch backyard. Passersby would 1~g a rnrrror. Working with with a number of professional often stop and be invited to hght from a window and ker astronomers. -

PDF of Angry Young

An gry Y o ung Man by the same author * autobiography THE LIVING HEDGE (Faber & Faber) HERON LAKE: A NORFOLK YEAR (Batchworth PresJ) on the crisis THE ANNIHILATION OF MAN (Faber & Faber) THE J\.IEANING OF HUMAN EXISTENCE (Faber & Faber) THE AGE OF TERROR (Faber & Faber) no veis FUGITIVE MORNING (Denis Archer) PERIWAKE: HIS ODYSSEY (Denis Archer) MEN IN MA Y ( Gollancz:.) on the youth movement THE FOLK TRAlL (Noe! Douglas) THE GREEN COMPANY (The C. W. Daniel Co.) REPUBLIC OF CHILDREN (Alten & Unwin) poems EXI LE AND OTHER POEMS (The Caravel Press) LESLIE PAUL ANGRY YOUNG MAN F ABER AND F ABER LTD 24 Russell Square London First published in mcmli by Faber and Faber Limited 24 Russel! Square London W.C.I Second impression mcmlii ' Printed in Great Britain by Page Brothers (Norwich) Ltd All rights reserved To my brothers and sisters, above all to the youngest, J OAN and DouGLAS Contents I. THE BOY ON THE BEACH I p age I Il. A YOUNG CHAP IN FLEET STREET 32 ' ' Ill. oH YOUNG MEN OH YOUNG COMRADES 50 IV. THE COUNCIL OF ACTION 75 V. DEATH OF AN INFORMER 92 VI. THE DEDICA TED LIFE I0 3 VII. DEATH OF A SPACE SELLER I27 VIII. EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVES I39 IX. THE LENINIST CIRCUS I 55 ' ' X. NOTHING IS INNOCENT I 78 XI. DECLINE OF THE YOUTH MOVEMENT I 96 XII. DEATH OF A CHAR 20 7 XIII. RED POPLAR - GREY UNEMPLOYED 2I7 XIV. FESTIVAL AND TERROR 238 XV. THE NIGHT OF THE LAND-MINE 258 XVI. THE DAY OF THE SOLDIER 273 XVII. -

AB ADA ADB AI ALU APL ASEA ATP Ada Adam Adolf Afrika Aftonbladet

AB Elite Jugoslavien Nokia TTL abstrakt aktiviteter ADA Ellemtel Jungefeldt Norge TV abstrakta aktivt ADB Elmer Jungfrudansen Nyk|ping Tanzania abstraktion aktris AI Elof J{msh|g Nykoping Tarja absurd aktualisera ALU Elveborg Jamshog Nykoeping Tektronix absurditet aktualisering APL Emacs Jaemshoeg Nyqvist Telfer absurt aktualitet ASEA Enhagsv{gen J{rf{lla Nystr|m Telub acceleration aktuell ATP Enhagsvagen Jarfalla Nystrom Texas accelerator aktuella Ada Enhagsvaegen Jaerf{lla Nystroem Thorelli acceleratorer aktuellt Adam Enk|ping J{rstorp N{rke Tibble accelererad akt|r Adolf Enkoping Jarstorp Narke Tierp accent aktor Afrika Enkoeping Jaerstorp Naerke Tim accentuera aktoer Aftonbladet Eric J{rva N{slund Tjeckoslovakien acceptabel akustik Alf Erik Jarva Naslund Torberger acceptabelt akustisk Almunge Erlandsson Jaerva Naeslund Torsten acceptabla akustiska Althin Escher J{rvaborna N{swall Towards acceptera akustiskt Amdahl Eskil Jarvaborna Naswall Trelleborg access akut Amerika Eskilstuna Jaervaborna Naeswall Trender accessa akuta Amis Esselte J|nk|ping Odensala Tunisien ack akvarell Anders Ethernet Jonkoping Odhelius Turing ackompanjera al Andersson Euclid Joenk|ping Olle Tynning| ackumulativ alarm Anderstorpsv{gen Eunice KTH Olof Tynningo ackumulativa albert Anderstorpsvagen Euroc Kahn Olsson Tynningoe ackumulator album Anderstorpsvaegen Europa Kajsa Oskarshamn Tyskland ackumulatorn aldrig Andrews Eva Kalix Oslo T{by ackumulera ale Anita FORTRAN Kalle Osquar Taby adagio alert Ankeborg Ford Kallh{ll Osquarulda Taeby adapter alexi Anna Forsell -

Mellish Correspondence

Nov. 25. 1966 Daniel H. Harris Lunar and Planetary Laboratory University of Arizona 85721 Dear Mr. Harris: Your letter of the 17th. was forwarded to me here and it just arrived. I am very glad to hear from you and I have been trying to get over there to see all the wonders of those new wonderful telescopes but have had many things keep me busy and did not get aroubd (sic) to it yet but now that your letter is here it gives me more interest in visiting those wonderful instruments than ever. I am going to visit Cave also on my next trip to the south. Carpenter was very much interested in the craters on Mars being shown on the satelite (sic) pictures because I had told him of my seeing them in 1915 and as no one else had ever seen them, most people thought I must have been mistaken. Carpenter had been telling many people in the past 20 or 30 years about my seeing the craters in 1915 and some of the people thought I must have been mistaken. There are some drawings of Mars that I will show you when I come that may be of real value in the next serries (sic) of pictures of Mars taken with future satelites. (sic) One thing that I am stuck on is that the morning I saw all those craters and mountains I saw very plainly , one crater 200 miles or about that diameter and very deep . It looked to me as if it were three or four miles deep and it was very circular. -

Topographic Map of Mars

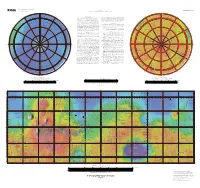

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR OPEN-FILE REPORT 02-282 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Prepared for the NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION 180° 0° 55° –55° Russell Stokes 150°E NOACHIS 30°E 210°W 330°W 210°E NOTES ON BASE smooth global color look-up table. Note that the chosen color scheme simply 330°E Darwin 150°W This map is based on data from the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA) 30°W — 60° represents elevation changes and is not intended to imply anything about –60° Chalcoporous v (Smith and others 2001), an instrument on NASA’s Mars Global Surveyor Milankovic surface characteristics (e.g. past or current presence of water or ice). These two (MGS) spacecraft (Albee and others 2001). The image used for the base of this files were then merged and scaled to 1:25 million for the Mercator portion and Rupes map represents more than 600 million measurements gathered between 1999 1:15,196,708 for the two Polar Stereographic portions, with a resolution of 300 and 2001, adjusted for consistency (Neumann and others 2001 and 2002) and S dots per inch. The projections have a common scale of 1:13,923,113 at ±56° TIA E T converted to planetary radii. These have been converted to elevations above the latitude. N S B LANI O A O areoid as determined from a martian gravity field solution GMM2 (Lemoine Wegener a R M S s T u and others 2001), truncated to degree and order 50, and oriented according to IS s NOMENCLATURE y I E t e M i current standards (see below). -

Can We See Martian Craters from Earth? By: Jeff Beish (Revised 01/15/2019)

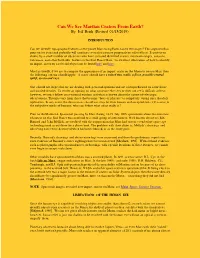

Can We See Martian Craters From Earth? By: Jeff Beish (Revised 01/15/2019) INTRODUCTION Can we identify topographic features on the planet Mars using Earth-based telescopes? This argument has gone on for years and probably will continue even after counter proposals are offered here. It centers on claims by a small number of observers who have seen and identified craters, mountain ranges, canyons, volcanoes, and other Earth-like feature on the Red Planet Mars. An excellent illustration of how to identify an impact crater on a celestial object can be found here and here. Most assuredly, if we are to compare the appearance of an impact crater on the Moon to one on Mars then the following criteria should apply: A crater should have a raised rim, walls, a floor, possible central uplift, ejecta and rays. One should not forget that we are dealing with personal opinions and are often predicated on some loose and untried theories. To render an opinion on what someone else sees or does not see is difficult at best; however, we must follow conventional wisdom and what is known about the nature of telescopic observations. Theories vary from those that become "laws of physics" to completely wrong ones that defy replication. In any event, the discussions should not stray far from known and accepted facts. Of course, in the subjective minds of humans, who can define what a fact really is? Prior to the Mariner-4 Spacecraft passing by Mars during 14-15 July 1965 speculation about the existence of craters on this Red Planet was confined to a small group of astronomers. -

The Heard Island Project Including the 2014 Cordell Expedition to Heard Island, Territory of Australia

A Brief Description of The Heard Island Project Including the 2014 Cordell Expedition to Heard Island, Territory of Australia Robert W. Schmieder, Ph.D. Version 5.2 15 Oct. 2012 Cordell Expeditions 4295 Walnut Blvd. Walnut Creek, CA 94596 (925) 934-3735 [email protected] www.cordell.org The Heard Island Project Version 5.2 (Latest version at www.heardisland.org) Page 1 of 87 This Document This document provides a brief description of the Heard Island Project, particularly the proposed 2014 Cordell Expedition to Heard Island, Territory of Australia, in the Southern Ocean. It was prepared specifically for the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD) in support of an application for a permit to visit Heard Island in the time frame Jan.-Feb., 2014. The material herein was compiled by Dr. Robert W. Schmieder, Director and Expedition Leader for Cordell Expeditions, a nonprofit scientific organization based in Walnut Creek, California. Significant portions of this document were contributed by Christian Janssen, Ken Ehrhart, Dr. Steve Smith, and other members of Cordell Expeditions. Heard Island is managed by the AAD under the Heard Island and McDonald Islands Marine Reserve Management Plan of 2005. The foreword of that plan contains the following statement: This management plan includes measures to ensure that the Reserve’s values are identified, protected and communicated to the public, most of whom will never visit this remote, wild and special place. In particular the Plan includes comprehensive measures designed to prevent the introduction of alien species from human activities, to ensure protection of important terrestrial and marine species, habitats and ecosystems, and to interpret the cultural heritage values associated with 19th century sealing activities and the earliest Australian National Antarctic Research Expedition. -

Colonization: a Permanent Habitat for the Colonization of Mars

COLONIZATION A PERMANENT HABITAT FOR THE COLONIZATION OF MARS A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master in Engineering Science (Research) in Mechanical Engineering BY MATTHEW HENDER THE UNIVERSITY OF AD ELAIDE SCHOOL OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING SUPERVISOR S – DR. GERALD SCHNEIDER & COLIN HANSEN A u g u s t 2 0 0 9 315°E (45°W) 320°E (40°W) 325°E (35°W) 330°E (30°W) 335°E (25°W) 340°E (20°W) 345°E (15°W) 350°E (10°W) 355°E (5°W) 360°E (0°W) 0° 0° HYDRAOTES CHAOS . llis Dia-Cau Va vi Ra . Camiling Aromatum Chaos . Rypin Chimbote . Mega . IANI MERIDIANI PLANUM* . v Wicklow Windfall Zulanka Pinglo . Oglala Tuskegee . Bamba . CHAOS . Bahn . Locana. Tarata . Spry Manti Balboa ARABIA Huancayo . AUREUM . Groves . Vaals . Conches _ . Sitka Berseba . Kaid . Chinju Lachute . Manah Rakke CHAOS . Stobs . Byske -5° . Airy-0 . -5° Butte. Azusa Kong Timbuktu . Quorn Airy . Creel . Innsbruck XANTHE Wink TERRA TERRA A . Kholm M . Daet S A Ganges .Sfax . Paks H Batoka C Chasma . Rincon I Arsinoes . Glide R P AURORAE CHAOS A Chaos C I S E R M R I N A E R R F G A I T I A R -10° -10° M Pyrrhae C H A O S S Chaos E L L A V MARGARITIFER Eos Mensa* EOS CHASMA Beer -15° -15° alles V L o i r e Osuga Eos TERRA Chaos V a Jones l l e s Vinogradov -20° Lorica Polotsk -20° s Sigli . Kimry . Lebu Valle S Kansk .