Phase I Archaeological Survey Report Summarizing the Results of Tasks 1-5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parker Adkins & Blue

Parker Adkins & Blue Sky: Was Their Story Possible? June 2, 2017 / Parker Adkins (links removed) Researched & written by Sarah (Sallie) Burns Atkins Lilburn, Georgia June, 2017 INTRODUCTION Parker Adkins’s parents, William Atkinson (Adkins) and Elizabeth Parker were married on January 17, 1716, at St. John’s Church in Richmond, Virginia. One branch of Parker’s descendants has embraced the story that, in addition to the children he had with his wife, Mary, he had two children by a daughter of Chief Cornstalk named Blue Sky and when Blue Sky died, Parker took his two half-Shawnee children, Littleberry and Charity, home to his wife, Mary, who raised them along with their other children. No proof existed, one way or another, until 2016 when a direct female descendant of Charity Adkins was located and agreed to have her mitochondrial DNA analyzed. Mitochondrial DNA traces a female’s maternal ancestry, mother-to-mother-to-mother, back through time. The DNA came back as Haplogroup H, the most common female haplogroup in Europe. Charity’s mother was a white woman with mostly English and Irish ancestry. Many other women match her descendant’s DNA kit, all of them with the same basic ancestry. Some members of the Adkins family who have long embraced Blue Sky as their ancestor did not accept the DNA results so I researched and put together the following paper trail in an attempt to validate the story, beginning with Littleberry and Charity Adkins. This information was posted on the Adkins Facebook page over a period of time. I have consolidated the posts into one document – a future reference for everyone who has heard or is interested in this story. -

West Virginia and Regional History Collection Newsletter Twenty-Year Index, Volume 1-Volume 20, Spring 1985-Spring 2005 Anna M

West Virginia & Regional History Center University Libraries Newsletters 2012 West Virginia and Regional History Collection Newsletter Twenty-Year Index, Volume 1-Volume 20, Spring 1985-Spring 2005 Anna M. Schein Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvrhc-newsletters Part of the History Commons West Virginia and Regional History Collection Newsletter Twenty-Year Index Volume 1-Volume 20 Spring 1985-Spring 2005 Compiled by Anna M. Schein Morgantown, WV West Virginia and Regional History Collection West Virginia University Libraries 2012 1 Compiler’s Notes: Scope Note: This index includes articles and photographs only; listings of WVRHC staff, WVU Libraries Visiting Committee members, and selected new accessions have not been indexed. Publication and numbering notes: Vol. 12-v. 13, no. 1 not published. Issues for summer 1985 and fall 1985 lack volume numbering and are called: no. 2 and no.3 respectively. Citation Key: The volume designation ,“v.”, and the issue designation, “no.”, which appear on each issue of the Newsletter have been omitted from the index. 5:2(1989:summer)9 For issues which have a volume number and an issue number, the volume number appears to left of colon; the issue number appears to right of colon; the date of the issue appears in parentheses with the year separated from the season by a colon); the issue page number(s) appear to the right of the date of the issue. 2(1985:summer)1 For issues which lack volume numbering, the issue number appears alone to the left of the date of the issue. Abbreviations: COMER= College of Mineral and Energy Resources, West Virginia University HRS=Historical Records Survey US=United States WV=West Virginia WVRHC=West Virginia and Regional History Collection, West Virginia University Libraries WVU=West Virginia University 2 West Virginia and Regional History Collection Newsletter Index Volume 1-Volume 20 Spring 1985-Spring 2005 Compiled by Anna M. -

West Virginia Service Locations

West Virginia | Service Location Report 2020 YEAR IN REVIEW AmeriCorps City Service Locations Project Name Program Type Completed* Current Sponsor Organization Participants Participants Accoville BUFFALO ELEMENTARY Energy Express AmeriCorps AmeriCorps State 3 - SCHOOL West Virginia University Research Corp Addison (Webster Catholic Charities Weston LifeBridge AmeriCorps AmeriCorps State 1 - Springs) Region - Webster United Way of Central West Virginia Addison (Webster Webster County Energy Express AmeriCorps AmeriCorps State 6 - Springs) West Virginia University Research Corp Addison (Webster WEBSTER SPRINGS Energy Express AmeriCorps AmeriCorps State 3 - Springs) ELEMENTARY SCHOOL West Virginia University Research Corp Bartow Wildlife Intern - Greenbrier Monongahela National Forest AmeriCorps National - 1 Mt. Adams Institute Basye Hardy County Convention and WV Community Development Hub AmeriCorps VISTA 1 - Visitors' Bureau WV Community Development Hub Bath (Berkeley Springs) Morgan County Starting Points West Virginia's Promise AmeriCorps VISTA 8 - WV Commission for National and Community Service Bath (Berkeley Springs) Wind Dance Farm & Earth West Virginia's Promise AmeriCorps VISTA 4 1 Education Center WV Commission for National and Community Service Beaver New River Community & AmeriCorps on the Frontline of School Success AmeriCorps State 1 1 Technical College The Education Alliance Beckley Active Southern West Virginia National Coal Heritage Area Authority AmeriCorps VISTA 1 1 National Coal Heritage Area Authority Beckley BECKLEY -

BARBOUR Audra State Park WV Dept. of Commerce $40,798 Barbour County Park Incl

BARBOUR Audra State Park WV Dept. of Commerce $40,798 Barbour County Park incl. Playground, Court & ADA Barbour County Commission $381,302 Philippi Municipal Swimming Pool City of Philippi $160,845 Dayton Park Bathhouse & Pavilions City of Philippi $100,000 BARBOUR County Total: $682,945 BERKELEY Lambert Park Berkeley County $334,700 Berkeley Heights Park Berkeley County $110,000 Coburn Field All Weather Track Berkeley County Board of Education $63,500 Martinsburg Park City of Martinsburg $40,000 War Memorial Park Mini Golf & Concession Stand City of Martinsburg $101,500 Faulkner Park Shelters City of Martinsburg $60,000 BERKELEY County Total: $709,700 BOONE Wharton Swimming Pool Boone County $96,700 Coal Valley Park Boone County $40,500 Boone County Parks Boone County $106,200 Boone County Ballfield Lighting Boone County $20,000 Julian Waterways Park & Ampitheater Boone County $393,607 Madison Pool City of Madison $40,500 Sylvester Town Park Town of Sylvester $100,000 Whitesville Pool Complex Town of Whitesville $162,500 BOONE County Total: $960,007 BRAXTON Burnsville Community Park Town of Burnsville $25,000 BRAXTON County Total: $25,000 BROOKE Brooke Hills Park Brooke County $878,642 Brooke Hills Park Pool Complex Brooke County $100,000 Follansbee Municipal Park City of Follansbee $37,068 Follansbee Pool Complex City of Follansbee $246,330 Parkview Playground City of Follansbee $12,702 Floyd Hotel Parklet City of Follansbee $12,372 Highland Hills Park City of Follansbee $70,498 Wellsburg Swimming Pool City of Wellsburg $115,468 Wellsburg Playground City of Wellsburg $31,204 12th Street Park City of Wellsburg $5,786 3rd Street Park Playground Village of Beech Bottom $66,000 Olgebay Park - Haller Shelter Restrooms Wheeling Park Commission $46,956 BROOKE County Total: $1,623,027 CABELL Huntington Trail and Playground Greater Huntington Park & Recreation $113,000 Ritter Park incl. -

“A People Who Have Not the Pride to Record Their History Will Not Long

STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE i “A people who have not the pride to record their History will not long have virtues to make History worth recording; and Introduction no people who At the rear of Old Main at Bethany College, the sun shines through are indifferent an arcade. This passageway is filled with students today, just as it was more than a hundred years ago, as shown in a c.1885 photograph. to their past During my several visits to this college, I have lingered here enjoying the light and the student activity. It reminds me that we are part of the past need hope to as well as today. People can connect to historic resources through their make their character and setting as well as the stories they tell and the memories they make. future great.” The National Register of Historic Places recognizes historic re- sources such as Old Main. In 2000, the State Historic Preservation Office Virgil A. Lewis, first published Historic West Virginia which provided brief descriptions noted historian of our state’s National Register listings. This second edition adds approx- Mason County, imately 265 new listings, including the Huntington home of Civil Rights West Virginia activist Memphis Tennessee Garrison, the New River Gorge Bridge, Camp Caesar in Webster County, Fort Mill Ridge in Hampshire County, the Ananias Pitsenbarger Farm in Pendleton County and the Nuttallburg Coal Mining Complex in Fayette County. Each reveals the richness of our past and celebrates the stories and accomplishments of our citizens. I hope you enjoy and learn from Historic West Virginia. -

Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society, Vol. 20, No

BULLETIN OF THE MASSACI-IUSETTS ARCI-IAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY, INC. ~ VOL. xx NO.4 JULY, 1959 CONTENTS j Page ADENA AND BLOCK-END TUBES IN THE NORTHEAST By DouGLAS F. JORDAN 49 SOME INDIAN BURIALS FROM SOUTHEASTERN MASSACHUSElTS. PART 2-THE WAPANUCKET BURIALS By MAURICE ROBBINS 61 INDEX - VOLUME X 68 PUBUSHED BY THE MASSACHUsmS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY, INC. LEAMAN F. HALLE'IT, Editor, 31 West Street, Mansfield, Mass. MABEL A. ROBBINS, Secretary, Bronson Museum, 8 No. Main St., Attleboro, Mass. SOCIETY OFFICERS President Eugene C. Winter, Jr. 1st Vice President Viggo C. Petersen 2nd Vice President Arthur C. Lord Secretary Mabel A. Robbins Treasurer Arthur C. Staples Editor Leaman F. Hallett TRUSTEES Society OHicers and Past President Ex-Officio Robert D. Barnes 1956-1959 Guy Mellgren, Jr. 1956-1959 J. Alfred Mansfield 1957-1960 Waldo W. Horne 1957-1960 Theodore L Stoddard 1958-1961 William D. Brierly 1958-1961 COMMITTEE CHAIRMEN Research Council Douglas F. Jordan Council Chairmen- Site Survey, June Barnes; Historical Research, L. F. Hallett; at Large, G. Mellgren; Cousultants, J. O. Brew and D. S. Byers. Committee on Education Maurice Robbins Museum Director, Maurice Robbins Museum Curator, William S. Fowler Committee on Publications Leaman F. Hallett Chapter Expansion Willard C. Whiting Program Committee Walter Vosberg Nominating Committee Robert D. Barnes Committee on Resolutions Rachel Whiting Auditing Committee Edward Lally Librarian Clifford E. Kiefer CHAPTER CHAIRMEN Cohannet Chapter-Harold F. Nye W. K. Moorehead Chapter- Connecticut Valley Chapter- A. L Studley W. R. Young Northeastern Chapter-Robert Valyou W. Elmer Ekblaw Chapter- Sippican Chapter-L. P. Leonard Ie. B. -

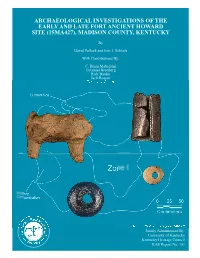

Cvr Design V2.Ai

ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS OF THE EARLY AND LATE FORT ANCIENT HOWARD SITE (15MA427), MADISON COUNTY, KENTUCKY By David Pollack and Eric J. Schlarb With Contributions By: C. Brian Mabelitini Emanuel Breitburg Rick Burdin Jack Rossen Wesley D. Stoner Kentucky Archaeological Survey Jointly Administered By: University of Kentucky Kentucky Heritage Council KAS Report No. 151 ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS OF THE EARLY AND LATE FORT ANCIENT HOWARD SITE (15MA427), MADISON COUNTY, KENTUCKY KAS Report No. 151 By David Pollack and Eric J. Schlarb With Contributions by: C. Brian Mabelitini Emanuel Breitburg Rick Burdin Jack Rossen Wesley D. Stoner Report Prepared for: James Howard Richmond Industrial Development Corporation Report Submitted by: Kentucky Archaeological Survey Jointly Administered by: University of Kentucky Kentucky Heritage Council 1020A Export Street Lexington, Kentucky 40506-9854 859/257-5173 February 2009 __________________________ David Pollack Principal Investigator ABSTRACT The Howard site contains the remains of an early Fort Ancient hamlet and a late Fort Ancient/Contact period village. The early Fort Ancient component is represented by Jessamine Series ceramic and Type 2 Fine Triangular projectile points, while the late Fort Ancient component is represented by Madisonville series ceramics, Type 4 and Type 6 Fine Triangular projectile points, and unifacial and bifacial endscrapers. The presence of a marginella shell bead and mica fragments reflect long distance interaction with groups living to the south, and the recovery of a glass bead and a copper bead points to interaction with Europeans. Based on the presence of intact subplowzone deposits associated with both components, and the recovery of human remains, the Howard site is eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. -

And Eighteenth-Century Indian Life in Kentucky Author(S): A

Kentucky Historical Society Dispelling the Myth: Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Indian Life in Kentucky Author(s): A. Gwynn Henderson Source: The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, Vol. 90, No. 1, "The Kentucky Image" (Bicentennial Issue), pp. 1-25 Published by: Kentucky Historical Society Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23382492 Accessed: 25-09-2018 15:28 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Kentucky Historical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society This content downloaded from 128.163.2.206 on Tue, 25 Sep 2018 15:28:21 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Dispelling the Myth: Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Indian Life in Kentucky by A. Gwynn Henderson Misconceptions about the people who lived in what is now the state of Kentucky before it was settled by Euro-Americans and Afro-Americans take many forms. These incorrect ideas range from the specific (how the native peoples dressed, how their houses appeared, how they made their living, what language they spoke) to the general (the diversity of their way of life, the length of their presence here, their place of origin, their spiritual beliefs, and the organization of their political and economic systems). -

Marpiyawicasta Man of the Clouds, Or “L.O

MARPIYAWICASTA MAN OF THE CLOUDS, OR “L.O. SKYMAN” “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project Man of the Clouds HDT WHAT? INDEX MAN OF THE CLOUDS MARPIYAWICASTA 1750 Harold Hickerson has established that during the 18th and early 19th Centuries, there was a contested zone between the Ojibwa of roughly Wisconsin and the Dakota of roughly Minnesota that varied in size from 15,000 square miles to 35, 000 square miles. In this contested zone, because natives entering the region to hunt were “in constant dread of being surprised by enemies,” game was able to flourish. At this point, however, in a war between the Ojibwa and the Dakota for control over the wild rice areas of northern Minnesota (roughly a quarter of the caloric intake of these two groups was coming from this fecund wild rice plant of the swampy meadows) , the Ojibwa decisively won. HDT WHAT? INDEX MARPIYAWICASTA MAN OF THE CLOUDS HDT WHAT? INDEX MAN OF THE CLOUDS MARPIYAWICASTA This would have the ecological impact of radically increasing human hunting pressure within that previously protected zone. I have observed that in the country between the nations which are at war with each other the greatest number of wild animals are to be found. The Kentucky section of Lower Shawneetown (that was the main village of the Shawnee during the 18th Century) was established. Dr. Thomas Walker, a Virginia surveyor, led the first organized English expedition through the Cumberland Gap into what would eventually become Kentucky. -

2019 ASD Summer Activities Guide

1 This list of possible summer activities for families was developed to generate some ideas for summer fun and inclusion. Activities on the list do not imply any endorsement by the West Virginia Autism Training Center. Many activities listed are low cost or no cost. Remember to check your local libraries, YMCA, and Boys and Girls Clubs; they usually have fun summer activities planned for all ages. North Bend Rail Trail goes through numerous counties and can offer hours of fun outdoor time with various activities. At the bottom of this document are county extension offices. You may contact them for information for Clover buds, 4-H, Energy Express, Youth Volunteers and other activities that they host throughout WV. Link for their website: https://extension.wvu.edu/ County List and Information in Alphabetical Order Barbour County • WV Blue and Gray Trail; First Land Battle of Civil War http://www.blueandgrayreunion.org • Phillipi Covered Bridge & Museum Route 250, Phillipi, WV • Adaland Mansion www.adaland.org • Barbour County Historical Museum Mummies https://bestthingswv.com/unusual-attractions/ Berkeley County • Circa Blue Fest, June 7-9 http://www.circabluefest.com/ • Wonderment Puppet Theater Martinsburg 412 W King St 304-260-9382 • For The Kids By Geopre Children’s Museum Martinsburg 229 E. Martin St. 304-264-9977 • Galaxy Skateland Martinsburg 1201 3rd St. 304-263-0369 2 • JayDee’s Family Fun Center (304) 229-4343 Boone County • Upper Big Branch Miners Memorial http://www.ubbminersmemorial.com/ • Waterways https://www.facebook.com/waterwayswv • Coal River Festival (304) 419-4417 • Boone County Heritage & Arts Center Madison, WV http://www.boonecountywv.org/PDF/Boone-Heritage-and-Arts-Center.pdf Braxton County • Burnsville Dam/ Recreational Area https://www.recreation.gov/camping/gateways/315 • Sutton Lake https://www.suttonlakemarina.com/about-sutton-lake • Falls Mill https://www.facebook.com/pages/category/Community/Falls-Mill-West-Virginia- 144887218858429/ • Bulltown Historic Area 304-853-2371 • Monster Museum, 208 Main St. -

Measuring Ancient Works

Measuring Ancient Works Presented by Don Teter, PS ©2015 Donald L. Teter Measuring Ancient Works Cover page illustrations are a Scioto Valley burial mound and skull excavated therefrom by Squier and Davis “I can testify to little beyond the giant Mounds that the Savages say they guard as Curators, for some more distant Race of Builders. I have fail’d to observe more in them, than their most impressive Size, tho’ Mr. Dixon swears to Coded Inscriptions, Purposive Lamination, and Employment, unto the Present Day, by Agents Unknown of Powers Invisible.” Charles Mason, in Mason and Dixon, by Thomas Pynchon The Builders Adena (Early Woodland), Mississippian 1,000 BC – 200 BC 800 – 1600 AD Hopewell Fort Ancient 200 BC – 500 AD 1000 AD – 1750 AD Late Woodland Monongahela 500 – 1000 AD 1050 - 1635 Page 2 of 60 Measuring Ancient Works Page 3 of 60 Measuring Ancient Works Page 4 of 60 Measuring Ancient Works The Armstrong Culture is named for a creek in Fayette County, their mounds are smaller and less complex than the Adena. During the same period the Wilhelm Culture, named for a mound in Brooke County, was prevalent in the northern Panhandle and nearby areas in Pennsylvania. Page 5 of 60 Measuring Ancient Works Hopewell variants replaced the Armstrong and Wilhelm Cultures. The Armstrong seems to have evolved into the Buck Garden, named for a creek in Nicholas County. They used stone burial mounds and rock overhangs for their dead. The Watson Farm Culture, named for a mound in Hancock County, lived in the northern part of West Virginia. -

Desktop Analysis and Archaeological Reconnaissance Survey

Contract Publication Series WV11-060 DESKTOP ANALYSIS AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECONNAISSANCE SURVEY FOR THE PROPOSED EXPANSION / MODIFICATION OF THE BEECH RIDGE WIND ENERGY FACILITY, GREENBRIER COUNTY, WEST VIRGINIA by Christopher L. Nelson, Jamie S. Meece, & C. Michael Anslinger Prepared for Beech Ridge Energy II LLC Prepared by Lexington, KY Hurricane, WV Berlin Heights, OH Evansville, IN Longmont, CO Mt. Vernon, IL Sheridan, WY Shreveport, LA Contract Publication Series: WV11-060 DESKTOP ANALYSIS AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECONNAISSANCE SURVEY FOR THE PROPOSED EXPANSION / MODIFICATION OF THE BEECH RIDGE WIND ENERGY FACILITY, GREENBRIER COUNTY, WEST VIRGINIA Authored By: Christopher L. Nelson, MS, RPA Jamie S. Meece, MA, RPA C. Michael Anslinger, MA, RPA Submitted to: Erik Duncan Beech Ridge Energy II LLC 51 Monroe St., Suite 1604 Rockville, Maryland 20855 Voice: (304) 549-7696 Email: [email protected] Submitted by: Cultural Resource Analysts, Inc. 3556 Teays Valley Road, Suite 3 Hurricane, West Virginia 25526 Phone: (304) 562-7233 Fax: (304) 562-7235 Website: www.crai-ky.com CRA Project No.: W11I001 ______________________________ C. Michael Anslinger, RPA Principal Investigator August 25, 2011 Lead Agency: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service WVSHPO FR: 06-147-GB-35 MANAGEMENT SUMMARY Cultural Resource Analyst, Inc. conducted a desktop analysis and archaeological reconnaissance survey for the proposed expansion / modification of the Beech Ridge Wind Energy Facility in Greenbrier County, West Virginia (hereafter referred to as Project). Thirty-three turbines will be constructed as part of the Project but, for the purposes of this report, 47 turbine locations have been reviewed. This provides 14 alternate locations that could be utilized if one or more of the 33 turbine locations are not able to be constructed in their current proposed location.