Inquiry Into Procurement of Work by Westland District Council at Franz Josef

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making a Community: Filipinos in Wellington

Making a Community: Filipinos in Wellington September 2017 ISBN 978-0-9941409-4-4 (PDF) Making a Community: Filipinos in Wellington About the Author As an American living in New Zealand, I’ve been observing the debate here on immigration and multiculturalism. I arrived in Wellington last year with my Kiwi husband and three-year old son – and while settling in we’ve spent a lot of time discovering the delights of the city and its people. The experience also gave me some perspective on being a migrant far from home. I have a professional interest in South East Asian history, languages and culture - I just completed a PhD on the subject. I speak some Filipino, and am fascinated by the Philippines’ complex history. One of the major phenomena in the Philippines since the 1970s has been the growth of the global Filipino diaspora. That story has often been full of sadness. So I was intrigued by anecdotes of positivity and success from Wellington. Writing about how the migrant Filipino community has settled in New Zealand has been more than just a research project. It has highlighted how migration plays a role in community building. It also has meaning for me and my family’s future here. I really wanted to share some of the stories that I think reflect successful outcomes from immigration over the past thirty years. By Dr Rebecca Townsend 1 Key Points 1. 2. 3. Filipinos comprise 1 percent of Filipinos are a vital part of Most Filipinos in New Zealand are New Zealand’s population – the New Zealand’s dairy, healthcare, not Overseas Filipino Workers third largest Asian ethnic group construction, nursing, aged care, (OFW). -

Exposure to Coastal Flooding

Coastal Flooding Exposure Under Future Sea-level Rise for New Zealand Prepared for The Deep South Challenge Prepared by: Ryan Paulik Scott Stephens Sanjay Wadhwa Rob Bell Ben Popovich Ben Robinson For any information regarding this report please contact: Ryan Paulik Hazard Analyst Meteorology and Remote Sensing +64-4-386 0601 [email protected] National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research Ltd Private Bag 14901 Kilbirnie Wellington 6241 Phone +64 4 386 0300 NIWA CLIENT REPORT No: 2019119WN Report date: March 2019 NIWA Project: DEPSI18301 Quality Assurance Statement Reviewed by: Dr Michael Allis Formatting checked by: Patricia Rangel Approved for release by: Dr Andrew Laing © All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced or copied in any form without the permission of the copyright owner(s). Such permission is only to be given in accordance with the terms of the client’s contract with NIWA. This copyright extends to all forms of copying and any storage of material in any kind of information retrieval system. Whilst NIWA has used all reasonable endeavours to ensure that the information contained in this document is accurate, NIWA does not give any express or implied warranty as to the completeness of the information contained herein, or that it will be suitable for any purpose(s) other than those specifically contemplated during the Project or agreed by NIWA and the Client. Contents Executive summary ............................................................................................................. 6 1 Context for estimating coastal flooding exposure with rising seas ............................. 14 1.1 Coastal flooding processes in a changing climate .................................................. 14 1.2 National and regional coastal flooding exposure .................................................. -

Council Agenda

MASTERTON DISTRICT COUNCIL COUNCIL AGENDA WEDNESDAY 28 OCTOBER 2020 3.00 PM MEMBERSHIP Her Worship (Chairperson) Cr G Caffell Cr B Gare Cr D Holmes Cr B Johnson Cr G McClymont Cr F Mailman Cr T Nelson Cr T Nixon Cr C Peterson Cr S Ryan Noce is given that a meeng of the Masterton District Council will be held at 3.00pm on Wednesday 28 October 2020 at Waiata House, 27 Lincoln Rd, Masterton. RECOMMENDATIONS IN REPORTS ARE NOT TO BE CONSTRUED AS COUNCIL POLICY UNTIL ADOPTED 22 October 2020 Values 1. Public interest: members will serve the best interests of the people within the Masterton district and discharge their duties conscientiously, to the best of their ability. 2. Public trust: members, in order to foster community confidence and trust in their Council, will work together constructively and uphold the values of honesty, integrity, accountability and transparency. 3. Ethical behaviour: members will not place themselves in situations where their honesty and integrity may be questioned, will not behave improperly and will avoid the appearance of any such behaviour. 4. Objectivity: members will make decisions on merit; including appointments, awarding contracts, and recommending individuals for rewards or benefits. 5. Respect for others: will treat people, including other members, with respect and courtesy, regardless of their ethnicity, age, religion, gender, sexual orientation, or disability. Members will respect the impartiality and integrity of Council staff. 6. Duty to uphold the law: members will comply with all legislative requirements applying to their role, abide by this Code, and act in accordance with the trust placed in them by the public. -

THE HERITAGE NEW ZEALAND QUARTERLY UPDATE the New Zealand Heritage List / Rārangi Kōrero

THE HERITAGE NEW ZEALAND QUARTERLY UPDATE The New Zealand Heritage List / Rārangi Kōrero 28 April 2021 This is the first issue of the Heritage New Zealand Quarterly Update following the distribution of the Heritage New Zealand Annual Information on 20 January 2021. This update contains decisions on entries on the New Zealand Heritage List / Rārangi Kōrero (‘the List’) made at the Board and Māori Heritage Council meetings of 18 th February 2021 and Rārangi Kōrero Committee meetings of 28 th January 2021 and 18 th March 2021. The decisions relate to new entries, technical changes to existing entries, and reviews. This update also includes new proposals for entries on the List and heritage covenants. The next Quarterly Update will be issued in July 2021 covering the period April-June 2021. If you have not received your Heritage New Zealand Annual Information, please email [email protected] . Annie James Listing Advisor for Dr Michelle Horwood Manager Heritage Listing DDI (04) 470 8059 Email: [email protected] LOCAL AUTHORITIES: a copy of the Heritage New Zealand Annual Information should be kept at the front desk for the public to review on request. In This Quarterly Update Caution 2 Disclaimer 2 Exclusion of Liability 2 What’s New 3 New Listings 4 Covenants 11 Contact Details 17 Caution Heritage New Zealand advises persons searching the List in all cases, where possible, to utilise street address or the location description as a search reference. The names of places entered on the List should be carefully checked as the List often uses the historical names, particularly when a place or area is associated with an historical person, business, industry or past use. -

Three Waters

FOR DECISION MŌ TE WHAKATAUNGA TO Mayor and Councillors AUTHOR Adrian de Laborde Group Manager Engineering Services FILE REFERENCE Document: 2807302 Appendix A: Three Waters Reform Programme M2807311 Appendix B: 3 Waters Stimulus Funding Agreement M2807309 Appendix C: Simpson Grierson Advice SOLGM on MOU M2807308 Appendix D: Notional Funding Allocations M2807307 Appendix E: Eater Stimulus Delivery Plan M2807305 Appendix F: Grant Funding Guidance M2807248 PORTFOLIO HOLDER/S Councillor Ross Harris 3 Waters portfolio MEETING DATE 12 August 2020 SUBJECT Department of Internal Affairs 3-Waters Review Memorandum of Understanding SUMMARY | TE WHAKARĀPOPOTANGA This report provides an update on the Governments reform programme for 3 Waters and seeks approval for the Council to enter into a Memorandum of Understanding with the Crown. The decision is not considered to be a significant decision. Whaarangi 1 | 8 M 2807302 RECOMMENDATION | TE WHAIKUPU THAT the report be received. THAT the Council agrees to enter into a Memorandum of Understanding with the Crown, thus agreeing to participate in the initial stage of a central/local government three waters service delivery reform programme THAT the Council authorise the Chief Executive to enter into the Funding Agreement, to accept a grant from the Crown to spend on operating and/or capital expenditure relating to three waters infrastructure and service delivery THAT the Council considers these decisions to be insignificant under its Significance and Engagement Policy 2017. THAT the Council informs the community that the Memorandum of Understanding has been entered into. 1 PURPOSE | TE ARONGA This report provides an update to the Council on the Government’s progress on the reform of 3-Waters. -

Westland District Council Lifelines Assets

West Coast Lifelines Vulnerability and Interdependency Assessment Supplement 12: Westland District Council Lifelines Assets West Coast Civil Defence Emergency Management Group August 2017 IMPORTANT NOTES Disclaimer The information collected and presented in this report and accompanying documents by the Consultants and supplied to West Coast Civil Defence Emergency Management Group is accurate to the best of the knowledge and belief of the Consultants acting on behalf of West Coast Civil Defence Emergency Management Group. While the Consultants have exercised all reasonable skill and care in the preparation of information in this report, neither the Consultants nor West Coast Civil Defence Emergency Management Group accept any liability in contract, tort or otherwise for any loss, damage, injury or expense, whether direct, indirect or consequential, arising out of the provision of information in this report. This report has been prepared on behalf of West Coast Civil Defence Emergency Management Group by: Ian McCahon BE (Civil), David Elms BA, MSE, PhD Rob Dewhirst BE, ME (Civil) Geotech Consulting Ltd 21 Victoria Park Road Rob Dewhirst Consulting Ltd 29 Norwood Street Christchurch 38A Penruddock Rise Christchurch Westmorland Christchurch Hazard Maps The hazard maps contained in this report are regional in scope and detail, and should not be considered as a substitute for site-specific investigations and/or geotechnical engineering assessments for any project. Qualified and experienced practitioners should assess the site-specific hazard potential, including the potential for damage, at a more detailed scale. Cover Photo: Franz Josef Oxidation Ponds, March 2016. Photo from West Coast Regional Council West Coast Lifelines Vulnerability and Interdependency Assessment Supplement 12: Westland District Council Lifeline Assets . -

Natural Hazard Assessment for the Township of Franz Josef, Westland District Natural Hazard Assessment for the Township of Franz

Natural Hazard Assessment for the Township of Franz Josef, Westland District R.M. Langridge J.D. Howarth R. Buxton W.F. Ries GNS Science Consultancy Report 2016/33 July 2016 DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared by the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited (GNS Science) exclusively for and under contract to the Envirolink Fund/West Coast Regional Council. Unless otherwise agreed in writing by GNS Science, GNS Science accepts no responsibility for any use of or reliance on any contents of this report by any person other than the Envirolink Fund/West Coast Regional Council and shall not be liable to any person other than the Envirolink Fund/West Coast Regional Council, on any ground, for any loss, damage or expense arising from such use or reliance. Use of Data: Date that GNS Science can use associated data: July 2016 BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCE Langridge, R.M.; Howarth, J.D.; Buxton, R., Ries, W.F. 2016. A Natural Hazard Assessment for the Township of Franz Josef, Westland District, GNS Science Consultancy Report 2016/33. 61 p. Project Number 430W4150 Confidential 2016 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... IV 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 1 1.1 SCOPE OF WORK ............................................................................................... 2 1.2 PROJECT DESIGN ............................................................................................. -

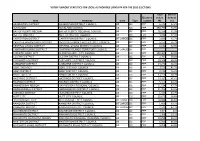

Voter Turnout Statistics for Local Authorities Using Fpp for the 2013 Elections

VOTER TURNOUT STATISTICS FOR LOCAL AUTHORITIES USING FPP FOR THE 2013 ELECTIONS Total Overall Electoral voters turnout Area Authority ward Type system (N) (%) ASHBURTON DISTRICT ASHBURTON DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 6,810 53.3% AUCKLAND AUCKLAND COUNCIL All CC FPP 292,790 34.9% BAY OF PLENTY REGION BAY OF PLENTY REGIONAL COUNCIL All RC FPP 78,938 41.0% BULLER DISTRICT BULLER DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 3,694 62.4% CARTERTON DISTRICT CARTERTON DISTRICT COUNCIL AT LARGE DC FPP 2,880 45.7% CENTRAL HAWKE'S BAY DISTRICT CENTRAL HAWKE'S BAY DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 5,151 55.2% CENTRAL OTAGO DISTRICT CENTRAL OTAGO DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 6,722 52.9% CHATHAM ISLANDS DISTRICT CHATHAM ISLANDS TERRITORY COUNCIL AT LARGE DC FPP CHRISTCHURCH CITY CHRISTCHURCH CITY COUNCIL All CC FPP 103,467 42.9% CLUTHA DISTRICT CLUTHA DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 2,707 59.8% FAR NORTH DISTRICT FAR NORTH DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 18,308 48.9% GISBORNE DISTRICT GISBORNE DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 14,272 48.3% GORE DISTRICT GORE DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 3720 41.7% GREY DISTRICT GREY DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 3,193 45.3% HAMILTON CITY HAMILTON CITY COUNCIL All CC FPP 37,276 38.3% HASTINGS DISTRICT HASTINGS DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 19,927 47.8% HAURAKI DISTRICT HAURAKI DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 5,375 40.4% HAWKE'S BAY REGION HAWKE'S BAY REGIONAL COUNCIL All RC FPP 51,524 47.7% HOROWHENUA DISTRICT HOROWHENUA DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 11,700 52.9% HURUNUI DISTRICT HURUNUI DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 1,327 44.7% HUTT CITY HUTT CITY COUNCIL All CC FPP -

Agenda Rārangi Take Notice of an Ordinary Meeting of Council

AGENDA RĀRANGI TAKE NOTICE OF AN ORDINARY MEETING OF COUNCIL to be held on Thursday, 25 February 2021 commencing at 1.00pm in the Council Chambers, 36 Weld Street, Hokitika and via Zoom Chairperson: His Worship the Mayor Members: Cr Carruthers (Deputy) Cr Davidson Cr Hart Cr Hartshorne Cr Kennedy Cr Keogan Cr Martin Cr Neale Kw Tumahai Kw Madgwick In accordance with clause 25B of Schedule 7 of the Local Government Act 2002, members may attend the meeting by audio or audiovisual link. 25.02.21 Council Meeting Agenda Page - 1 Council Vision: We work with the people of Westland to grow and protect our communities, our economy and our unique natural environment. Purpose: The Council is required to give effect to the purpose of local government as prescribed by section 10 of the Local Government Act 2002. That purpose is: (a) To enable democratic local decision-making and action by, and on behalf of, communities; and (b) To promote the social, economic, environmental, and cultural well-being of communities in the present and for the future. 1. KARAKIA TĪMATANGA OPENING KARAKIA 2. NGĀ WHAKAPAAHA APOLOGIES 3. WHAKAPUAKITANGA WHAIPĀNGA DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST Members need to stand aside from decision-making when a conflict arises between their role as a Member of the Council and any private or other external interest they might have. This note is provided as a reminder to Members to review the matters on the agenda and assess and identify where they may have a pecuniary or other conflict of interest, or where there may be a perception of a conflict of interest. -

Draft Long Term Plan 2018

WESTLAND DISTRICT COUNCIL Long Term Plan 2018-2028 Long Term Plan 1 CAUTIONARY NOTE Contents Long Term Plan 3 Contents 4 Westland District Council Contents Long Term Plan 5 6 Westland District Council INTRODUCTION 8 Message from the Mayor and Chief Executive 11 Westland District 15 Purpose of the Council 16 Intended Levels of Service 17 Key Challenges 19 Significant Forecasting Assumptions 22 Our Rating System INTRODUCTION Long Term Plan 7 MESSAGE FROM THE MAYOR AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE Message from the Mayor Westland District is a unique and special place. I have been fortunate in being elected by the Westland communities to be Mayor of this District. Looking ahead the next 10 years there are a number of challenges that lie ahead. I want to ensurethe steps that Council take are forward thinking and contribute towards growing, vibrant, thriving communities from Otira to Jacksons Bay and everywhere in between. As an elected Mayor my role is to ensure that the vision of the community aligns with the actions of Council. Through various community discussions and consultation processes, it is clear that the community want Council to ensure that core services are of an adequate standard and that all communities have access to these services. This Long Term Plan shows a clear shift in Council’s focus. The emphasis is now on improving levels of service for core activities and in many cases this requires increased spending (investment into these assets). In particular,three waters, roading, and the processing of consents are key areas. To ensure that these services are managed correctly, Council will ensure that it employs professional, competent people with the relevant skills and experience within these divisions. -

The Story of Christchurch, New Zealand

THE STORY OF CHRISTCHURCH, N.Z. JOHN ROBERT GODLEY, The Founder of Canterbury. THE STORY OF CHRISTCHURCH NEW ZEALAND. BY HENRY F. WIGRAM. CHRISTCHURCH: PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY THE LYTTELTON TIMES Co., LTH I91B. 430 PREFACE. The story of the foundation and early growth of Canterbury was first told to me, bit by bit, more than thirty years ago, some of it by men and women who had actually taken part in the founding of the settlement, and shaping its destiny, and some by late-comers, who had followed closely on the heels of the pioneers. There were many people then living who delighted in talking of their strenuous life in the pioneering days, " when all the world was young," and in telling of events which are now passing into silent history. Many of the stories I heard then are still vivid in my memory, little episodes illustrating the daily life of a community which had to do everything for itself survey, settle, stock and till the land, build its own roads, bridges and railways, form its own religious, educa- tional, political and social institutions, and construct its own local government. It is no wonder that coming from the valley of the Thames, where the results of centuries of civilisation had come to be accepted as the natural condition of nineteenth century existence, I found the contrast interesting and inspiring. My wife and I were received with the kindly hospi- tality so typical of the time and country. Amongst our immediate neighbours at Upper Riccarton were many old settlers. Mr. -

Communitrak™ Survey

COMMUNITRAK™ SURVEY PUBLIC PERCEPTIONS AND INTERPRETATIONS OF COUNCIL SERVICES AND REPRESENTATION PREPARED AS PART OF THE PUBLIC FEEDBACK PROGRAMME FOR: WESTLAND DISTRICT COUNCIL JANUARY / FEBRUARY 2020 National Research Bureau Ltd PO Box 10118, Mt Eden, Auckland, New Zealand P (09) 6300 655, www.nrb.co.nz CONTENTS SITUATION AND OBJECTIVES ................................................................................................................ 1 COMMUNITRAK™ SPECIFICATIONS .................................................................................................... 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................ 6 MAIN FINDINGS ..................................................................................................................................... 17 Council Services/Facilities............................................................................................................ 18 Residents overall ................................................................................................................. 19 i. Protection provided from dogs and wandering stock ................................ 19 ii. Parks and reserves ........................................................................................... 23 iii. Public toilets ..................................................................................................... 27 iv. The library services .........................................................................................