The Journal of the Georgia Philological Association

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1

Contents Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances .......... 2 February 7–March 20 Vivien Leigh 100th ......................................... 4 30th Anniversary! 60th Anniversary! Burt Lancaster, Part 1 ...................................... 5 In time for Valentine's Day, and continuing into March, 70mm Print! JOURNEY TO ITALY [Viaggio In Italia] Play Ball! Hollywood and the AFI Silver offers a selection of great movie romances from STARMAN Fri, Feb 21, 7:15; Sat, Feb 22, 1:00; Wed, Feb 26, 9:15 across the decades, from 1930s screwball comedy to Fri, Mar 7, 9:45; Wed, Mar 12, 9:15 British couple Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders see their American Pastime ........................................... 8 the quirky rom-coms of today. This year’s lineup is bigger Jeff Bridges earned a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his portrayal of an Courtesy of RKO Pictures strained marriage come undone on a trip to Naples to dispose Action! The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1 .......... 10 than ever, including a trio of screwball comedies from alien from outer space who adopts the human form of Karen Allen’s recently of Sanders’ deceased uncle’s estate. But after threatening each Courtesy of Hollywood Pictures the magical movie year of 1939, celebrating their 75th Raoul Peck Retrospective ............................... 12 deceased husband in this beguiling, romantic sci-fi from genre innovator John other with divorce and separating for most of the trip, the two anniversaries this year. Carpenter. His starship shot down by U.S. air defenses over Wisconsin, are surprised to find their union rekindled and their spirits moved Festival of New Spanish Cinema .................... -

The First Critical Assessments of a Streetcar Named Desire: the Streetcar Tryouts and the Reviewers

FALL 1991 45 The First Critical Assessments of A Streetcar Named Desire: The Streetcar Tryouts and the Reviewers Philip C. Kolin The first review of A Streetcar Named Desire in a New York City paper was not of the Broadway premiere of Williams's play on December 3, 1947, but of the world premiere in New Haven on October 30, 1947. Writing in Variety for November 5, 1947, Bone found Streetcar "a mixture of seduction, sordid revelations and incidental perversion which will be revolting to certain playgoers but devoured with avidity by others. Latter category will predomin ate." Continuing his predictions, he asserted that Streetcar was "important theatre" and that it would be one "trolley that should ring up plenty of fares on Broadway" ("Plays Out of Town"). Like Bone, almost everyone else interested in the history of Streetcar has looked forward to the play's reception on Broadway. Yet one of the most important chapters in Streetcar's stage history has been neglected, that is, the play's tryouts before that momentous Broadway debut. Oddly enough, bibliographies of Williams fail to include many of the Streetcar tryout reviews and surveys of the critical reception of the play commence with the pronouncements found in the New York Theatre Critics' Reviews for the week of December 3, 1947. Such neglect is unfortunate. Streetcar was performed more than a full month and in three different cities before it ever arrived on Broadway. Not only was the play new, so was its producer. Making her debut as a producer with Streetcar, Irene Selznick was one of the powerhouses behind the play. -

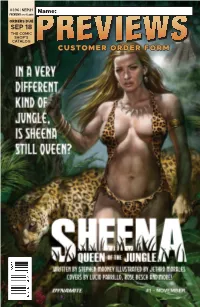

Customer Order Form

#396 | SEP21 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE SEP 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Sep21 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:51 AM GTM_Previews_ROF.indd 1 8/5/2021 8:54:18 AM PREMIER COMICS NEWBURN #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 A THING CALLED TRUTH #1 IMAGE COMICS 38 JOY OPERATIONS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 84 HELLBOY: THE BONES OF GIANTS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 86 SONIC THE HEDGEHOG: IMPOSTER SYNDROME #1 IDW PUBLISHING 114 SHEENA, QUEEN OF THE JUNGLE #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 132 POWER RANGERS UNIVERSE #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 184 HULK #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-4 Sep21 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:11 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Guillem March’s Laura #1 l ABLAZE The Heathens #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Fathom: The Core #1 l ASPEN COMICS Watch Dogs: Legion #1 l BEHEMOTH ENTERTAINMENT 1 Tuki Volume 1 GN l CARTOON BOOKS Mutiny Magazine #1 l FAIRSQUARE COMICS Lure HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS 1 The Overstreet Guide to Lost Universes SC/HC l GEMSTONE PUBLISHING Carbon & Silicon l MAGNETIC PRESS Petrograd TP l ONI PRESS Dreadnoughts: Breaking Ground TP l REBELLION / 2000AD Doctor Who: Empire of the Wolf #1 l TITAN COMICS Blade Runner 2029 #9 l TITAN COMICS The Man Who Shot Chris Kyle: An American Legend HC l TITAN COMICS Star Trek Explorer Magazine #1 l TITAN COMICS John Severin: Two-Fisted Comic Book Artist HC l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING The Harbinger #2 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Lunar Room #1 l VAULT COMICS MANGA 2 My Hero Academia: Ultra Analysis Character Guide SC l VIZ MEDIA Aidalro Illustrations: Toilet-Bound Hanako Kun Ark Book SC l YEN PRESS Rent-A-(Really Shy!)-Girlfriend Volume 1 GN l KODANSHA COMICS Lupin III (Lupin The 3rd): Greatest Heists--The Classic Manga Collection HC l SEVEN SEAS ENTERTAINMENT APPAREL 2 Halloween: “Can’t Kill the Boogeyman” T-Shirt l HORROR Trese Vol. -

BRIEF CHRONICLE Artistic Director the Official Newsmagazine of Writers’ Theatre Kathryn M

ISSUE twEnty-nInE MAY 2010 1 A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE: On Stage Table of ConTenTs Dear Friends .................................................................................................... 3 “DroppeD overboarD… on Stage: A Streetcar Named Desire ...................................................................... 5 The Man. The Play. The Legend. ........................................................ 6 Director's Sidebar .................................................................................... 10 into an ocean Acting Cromer ............................................................................................. 12 Setting the Scene ..................................................................................... 13 Why Here? Why Now? ............................................................................ 14 Announcing the 2010/11 Season ................................................. 16 baCksTage: as blue as Event Wrap Up – Behind-the-Scenes Brunch ........................... 20 Event Wrap Up – Literary Luncheon ............................................ 22 Sponsor Salute ........................................................................................... 24 Tales of a True Fourth Grade Nothing .......................................... 26 Performance Calendar .......................................................................... 29 my first lover’s eyes!” - blanChe, A Streetcar named desire 2 A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE: On Stage A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE: On Stage 1 Michael halberstam tHe -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

The Relevance of Tennessee Williams for the 21St- Century Actress

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Honors Theses Carl Goodson Honors Program 2009 Then & Now: The Relevance of Tennessee Williams for the 21st- Century Actress Marcie Danae Bealer Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses Part of the American Film Studies Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bealer, Marcie Danae, "Then & Now: The Relevance of Tennessee Williams for the 21st- Century Actress" (2009). Honors Theses. 24. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses/24 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Carl Goodson Honors Program at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Then & Now: The Relevance of Tennessee Williams for the 21st- Century Actress Marcie Danae Bealer Honors Thesis Ouachita Baptist University Spring 2009 Bealer 2 Finding a place to begin, discussing the role Tennessee Williams has played in the American Theatre is a daunting task. As a playwright Williams has "sustained dramatic power," which allow him to continue to be a large part of American Theatre, from small theatre groups to actor's workshops across the country. Williams holds a central location in the history of American Theatre (Roudane 1). Williams's impact is evidenced in that "there is no actress on earth who will not testify that Williams created the best women characters in the modem theatre" (Benedict, par 1). According to Gore Vidal, "it is widely believed that since Tennessee Williams liked to have sex with men (true), he hated women (untrue); as a result his women characters are thought to be malicious creatures, designed to subvert and destroy godly straightness" (Benedict, par. -

1.1 Biblical Wisdom

JOB, ECCLESIASTES, AND THE MECHANICS OF WISDOM IN OLD ENGLISH POETRY by KARL ARTHUR ERIK PERSSON B. A., Hon., The University of Regina, 2005 M. A., The University of Regina, 2007 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) February 2014 © Karl Arthur Erik Persson, 2014 Abstract This dissertation raises and answers, as far as possible within its scope, the following question: “What does Old English wisdom literature have to do with Biblical wisdom literature?” Critics have analyzed Old English wisdom with regard to a variety of analogous wisdom cultures; Carolyne Larrington (A Store of Common Sense) studies Old Norse analogues, Susan Deskis (Beowulf and the Medieval Proverb Tradition) situates Beowulf’s wisdom in relation to broader medieval proverb culture, and Charles Dunn and Morton Bloomfield (The Role of the Poet in Early Societies) situate Old English wisdom amidst a variety of international wisdom writings. But though Biblical wisdom was demonstrably available to Anglo-Saxon readers, and though critics generally assume certain parallels between Old English and Biblical wisdom, none has undertaken a detailed study of these parallels or their role as a precondition for the development of the Old English wisdom tradition. Limiting itself to the discussion of two Biblical wisdom texts, Job and Ecclesiastes, this dissertation undertakes the beginnings of such a study, orienting interpretation of these books via contemporaneous reception by figures such as Gregory the Great (Moralia in Job, Werferth’s Old English translation of the Dialogues), Jerome (Commentarius in Ecclesiasten), Ælfric (“Dominica I in Mense Septembri Quando Legitur Job”), and Alcuin (Commentarius Super Ecclesiasten). -

*P Ocket Sizes May Vary. W E Recommend Using Really, Really Big Ones

*Pocket sizes may vary. We recommend using really, really big ones. Table of Contents Welcome to Dragon*Con! .............................................3 Live Performances—Concourse (CONC) .................38 Film Festival Schedule ...............................................56 Vital Information .........................................................4 Online Gaming (MMO) .........................................91 Walk of Fame ...........................................................58 Important Notes ....................................................4 Paranormal Track (PN) .........................................92 Dealers Tables ..........................................................60 Courtesy Buses .....................................................4 Podcasting (POD) ................................................93 Exhibitors Booths ......................................................62 MARTA Schedule ..................................................5 Puppetry (PT) <NEW> .......................................94 Comics Artists Alley ...................................................64 Hours of Operation ................................................5 Reading Sessions (READ) .....................................96 Art Show: Participating Artists ....................................66 Special Events ......................................................6 Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time (RJWOT) ................96 Hyatt Atlanta Fan Tracks Information and Room Locations ...................6 Robotics and Maker Track -

Producing Tennessee Williams' a Streetcar Named Desire, a Process

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE SCHOOL OF THEATRE PRODUCING TENNESSEE WILLIAMS’ A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE, A PROCESS FOR DIRECTING A PLAY WITH NO REFUND THEATRE J. SAMUEL HORVATH Spring, 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Finance with honors in Theatre Reviewed and approved* by the following: Matthew Toronto Assistant Professor of Theatre Thesis Supervisor Annette McGregor Professor of Theatre Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. ABSTRACT This document chronicles the No Refund Theatre production of Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire. A non-profit, student organization, No Refund Theatre produces a show nearly every weekend of the academic year. Streetcar was performed February 25th, 26th, and 27th, 2010 and met with positive feedback. This thesis is both a study of Streetcar as a play, and a guide for directing a play with No Refund. It is divided into three sections. First, there is an analysis Tennessee Williams’ play, including a performance history, textual analysis, and character analyses. Second, there is a detailed description of the process by which I created the show. And finally, the appendices include documentation and notes from all stages of the production, and are essentially my directorial promptbook for Streetcar. Most importantly, embedded in this document is a video recording of our production of Streetcar, divided into three “acts.” I hope that this document will serve as a road-map for -

BAM Presents the Sydney Theatre Company Production of Tennessee Williams’ a Streetcar Named Desire, Nov 27–Dec 20

BAM presents the Sydney Theatre Company production of Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire, Nov 27–Dec 20 Production marks U.S. directorial debut of Liv Ullmann and features Cate Blanchett as Blanche DuBois, Joel Edgerton as Stanley, and Robin McLeavey as Stella The Wall Street Journal is the Presenting Sponsor of A Streetcar Named Desire A Streetcar Named Desire By Tennessee Williams Sydney Theatre Company Directed by Liv Ullmann Set design by Ralph Myers Costume design by Tess Schofield Lighting design by Nick Schlieper Sound design by Paul Charlier BAM Harvey Theater (651 Fulton St) Nov 27 and 28, Dec 1*, 2, 3**, 4, 5, 8–12, 15–19 at 7:30pm Nov 28, Dec 2, 5, 9, 12, 16, and 19 at 2pm Nov 29, Dec 6, 13, and 20 at 3pm Tickets: $30, 65, 95 (Tues–Thurs); $40, 80, 120 (Fri–Sun) 718.636.4100 or BAM.org *press opening **A Streetcar Named Desire: Belle Rêve Gala (performance begins at 8pm) Artist Talk with Liv Ullmann: Between Screen and Stage Moderated by Phillip Lopate, writer and professor at Columbia University. Dec 7 at 7pm BAM Harvey Theater Tickets: $15 ($7.50 for Friends of BAM) Artist Talk with cast members Moderated by Lynn Hirschberg, The New York Times Magazine editor-at-large Dec 8, post-show (free for same-day ticket holders) Brooklyn, N.Y./Oct 23, 2009—In a special winter presentation, Sydney Theatre Company returns to BAM with Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire, directed by renowned actor/director/writer Liv Ullmann and featuring Academy Award-winning actress/Sydney Theatre Company Co-Artistic Director Cate Blanchett as Blanche DuBois, Joel Edgerton at Stanley Kowalski, Robin McLeavey as Stella Kowalski, and Tim Richards as Mitch. -

AUDITIONS: Thursday, Jan

The at er Auditi ons Open Call for A Streetcar Named Desire By Tennessee Williams Directed by Margaret Knapp Blanche DuBois is an unmarried former schoolteacher and fading Southern belle. She arrives in the French Quarter of New Orleans to stay with her pregnant sister Stella and husband Stanley. Blanche is disdainful of the couple’s cramped quarters, though it is quickly revealed that Belle Reve, the palatial DuBois family home, has been lost and Blanche has nowhere else to go. Blanche’s genteel sensibility and judgmental nature brings out the worst in the hot-tempered, working class Stanley. Blanche, ever hopeful, sparks a romance with Stanley’s friend Mitch, until Stanley goes digging through her seamy past to destroy her hopes of a fresh start. When Stella goes into labor and leaves for the hospital, Stanley and Blanche are left alone in the apartment, and things come to a violent head. This Pulitzer Prize winning play had a long and successful run on Broadway and was made into a film starring Vivien Leigh (Blanche) and Marlon Brando (Stanley). A tragic and effective drama, it ranks as one of the greatest in American theater. ROLES: Seeking actors of all ages and ethnicities. People of color strongly encouraged to audition. AUDITIONS: Thursday, Jan. 24 6 - 9 p.m. Room A167, Skokie Campus, 7701 N. Lincoln Ave. No appointment necessary. Please be prepared to read from the script. CALLBACKS: Friday, Jan. 25, 6:30 - 9 p.m. Room A167, Skokie Campus, 7701 N. Lincoln Ave. The Skokie campus is accessible through the CTA yellow line. -

Third Person : Authoring and Exploring Vast Narratives / Edited by Pat Harrigan and Noah Wardrip-Fruin

ThirdPerson Authoring and Exploring Vast Narratives edited by Pat Harrigan and Noah Wardrip-Fruin The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England 8 2009 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. For information about special quantity discounts, please email [email protected]. This book was set in Adobe Chapparal and ITC Officina on 3B2 by Asco Typesetters, Hong Kong. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Third person : authoring and exploring vast narratives / edited by Pat Harrigan and Noah Wardrip-Fruin. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-262-23263-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Electronic games. 2. Mass media. 3. Popular culture. 4. Fiction. I. Harrigan, Pat. II. Wardrip-Fruin, Noah. GV1469.15.T48 2009 794.8—dc22 2008029409 10987654321 Index American Letters Trilogy, The (Grossman), 193, 198 Index Andersen, Hans Christian, 362 Anderson, Kevin J., 27 A Anderson, Poul, 31 Abbey, Lynn, 31 Andrae, Thomas, 309 Abell, A. S., 53 Andrews, Sara, 400–402 Absent epic, 334–336 Andriola, Alfred, 270 Abu Ghraib, 345, 352 Andru, Ross, 276 Accursed Civil War, This (Hull), 364 Angelides, Peter, 33 Ace, 21, 33 Angel (TV show), 4–5, 314 Aces Abroad (Mila´n), 32 Animals, The (Grossman), 205 Action Comics, 279 Aparo, Jim, 279 Adams, Douglas, 21–22 Aperture, 140–141 Adams, Neal, 281 Appeal, 135–136 Advanced Squad Leader (game), 362, 365–367 Appendixes (Grossman), 204–205 Afghanistan, 345 Apple II, 377 AFK Pl@yers, 422 Appolinaire, Guillaume, 217 African Americans Aquaman, 306 Black Lightning and, 275–284 Arachne, 385, 396 Black Power and, 283 Archival production, 419–421 Justice League of America and, 277 Aristotle, 399 Mr.