A Quotient Rule Integration by Parts Formula Jennifer Switkes ([email protected]), California State Polytechnic Univer- Sity, Pomona, CA 91768

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Brief but Important Note on the Product Rule

A brief but important note on the product rule Peter Merrotsy The University of Western Australia [email protected] The product rule in the Australian Curriculum he product rule refers to the derivative of the product of two functions Texpressed in terms of the functions and their derivatives. This result first naturally appears in the subject Mathematical Methods in the senior secondary Australian Curriculum (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA], n.d.b). In the curriculum content, it is mentioned by name only (Unit 3, Topic 1, ACMMM104). Elsewhere (Glossary, p. 6), detail is given in the form: If h(x) = f(x) g(x), then h'(x) = f(x) g'(x) + f '(x) g(x) (1) or, in Leibniz notation, d dv du ()u v = u + v (2) dx dx dx presupposing, of course, that both u and v are functions of x. In the Australian Capital Territory (ACT Board of Senior Secondary Studies, 2014, pp. 28, 43), Tasmania (Tasmanian Qualifications Authority, 2014, p. 21) and Western Australia (School Curriculum and Standards Authority, 2014, WACE, Mathematical Methods Year 12, pp. 9, 22), these statements of the Australian Senior Mathematics Journal vol. 30 no. 2 product rule have been adopted without further commentary. Elsewhere, there are varying attempts at elaboration. The SACE Board of South Australia (2015, p. 29) refers simply to “differentiating functions of the form , using the product rule.” In Queensland (Queensland Studies Authority, 2008, p. 14), a slight shift in notation is suggested by referring to rules for differentiation, including: d []f (t)g(t) (product rule) (3) dt At first, the Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority (2015, p. -

Notes on Calculus II Integral Calculus Miguel A. Lerma

Notes on Calculus II Integral Calculus Miguel A. Lerma November 22, 2002 Contents Introduction 5 Chapter 1. Integrals 6 1.1. Areas and Distances. The Definite Integral 6 1.2. The Evaluation Theorem 11 1.3. The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus 14 1.4. The Substitution Rule 16 1.5. Integration by Parts 21 1.6. Trigonometric Integrals and Trigonometric Substitutions 26 1.7. Partial Fractions 32 1.8. Integration using Tables and CAS 39 1.9. Numerical Integration 41 1.10. Improper Integrals 46 Chapter 2. Applications of Integration 50 2.1. More about Areas 50 2.2. Volumes 52 2.3. Arc Length, Parametric Curves 57 2.4. Average Value of a Function (Mean Value Theorem) 61 2.5. Applications to Physics and Engineering 63 2.6. Probability 69 Chapter 3. Differential Equations 74 3.1. Differential Equations and Separable Equations 74 3.2. Directional Fields and Euler’s Method 78 3.3. Exponential Growth and Decay 80 Chapter 4. Infinite Sequences and Series 83 4.1. Sequences 83 4.2. Series 88 4.3. The Integral and Comparison Tests 92 4.4. Other Convergence Tests 96 4.5. Power Series 98 4.6. Representation of Functions as Power Series 100 4.7. Taylor and MacLaurin Series 103 3 CONTENTS 4 4.8. Applications of Taylor Polynomials 109 Appendix A. Hyperbolic Functions 113 A.1. Hyperbolic Functions 113 Appendix B. Various Formulas 118 B.1. Summation Formulas 118 Appendix C. Table of Integrals 119 Introduction These notes are intended to be a summary of the main ideas in course MATH 214-2: Integral Calculus. -

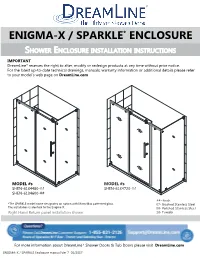

ENIGMA X Aka SPARKLE Enclosure Manual Ver 7 012017

ENIGMA-X / SPARKLE* ENCLOSURE SHOWER ENCLOSURE INSTALLATION INSTRUCTIONS IMPORTANT DreamLine® reserves the right to alter, modify or redesign products at any time without prior notice. For the latest up-to-date technical drawings, manuals, warranty information or additional details please refer to your model’s web page on DreamLine.com MODEL #s MODEL #s SHEN-6134480-## SHEN-6134720-## SHEN-6134600-## ##=finish *The SPARKLE model name designates an option with MirrorMax patterned glass. 07- Brushed Stainless Steel The installation is identical to the Enigma-X. 08- Polished Stainless Steel Right Hand Return panel installation shown 18- Tuxedo For more information about DreamLine® Shower Doors & Tub Doors please visit DreamLine.com ENIGMA-X / SPARKLE Enclosure manual Ver 7 01/2017 This model is treated with DreamLine’s exclusive ClearMaxTM Glass technology. This is a specially formulated coating that prevents the build up of soap and water spots. Install the surface with the ClearMaxTM label towards the inside of the shower. Please note that depending on the model, the glass may be coated on either one or both surfaces. For best results, squeegee the glass after each use and dry with a soft cloth. ENIGMA-X / SPARKLE Enclosure manual Ver 7 01/2017 2 B B A A C ! E IMPORTANT INFORMATION REGARDING THE INSTALLATION OF THIS SHOWER DOOR D PANEL DOOR F Right hand door installation shown as an example A Guide Rail Brackets must be firmly D Roller Guards must be postioned and attached to the wall. Installation into a secured within 1/16” of Upper Guide Rail. stud is strongly recommended. -

1 Approximating Integrals Using Taylor Polynomials 1 1.1 Definitions

Seunghee Ye Ma 8: Week 7 Nov 10 Week 7 Summary This week, we will learn how we can approximate integrals using Taylor series and numerical methods. Topics Page 1 Approximating Integrals using Taylor Polynomials 1 1.1 Definitions . .1 1.2 Examples . .2 1.3 Approximating Integrals . .3 2 Numerical Integration 5 1 Approximating Integrals using Taylor Polynomials 1.1 Definitions When we first defined the derivative, recall that it was supposed to be the \instantaneous rate of change" of a function f(x) at a given point c. In other words, f 0 gives us a linear approximation of f(x) near c: for small values of " 2 R, we have f(c + ") ≈ f(c) + "f 0(c) But if f(x) has higher order derivatives, why stop with a linear approximation? Taylor series take this idea of linear approximation and extends it to higher order derivatives, giving us a better approximation of f(x) near c. Definition (Taylor Polynomial and Taylor Series) Let f(x) be a Cn function i.e. f is n-times continuously differentiable. Then, the n-th order Taylor polynomial of f(x) about c is: n X f (k)(c) T (f)(x) = (x − c)k n k! k=0 The n-th order remainder of f(x) is: Rn(f)(x) = f(x) − Tn(f)(x) If f(x) is C1, then the Taylor series of f(x) about c is: 1 X f (k)(c) T (f)(x) = (x − c)k 1 k! k=0 Note that the first order Taylor polynomial of f(x) is precisely the linear approximation we wrote down in the beginning. -

Percent R, X and Z Based on Transformer KVA

SHORT CIRCUIT FAULT CALCULATIONS Short circuit fault calculations as required to be performed on all electrical service entrances by National Electrical Code 110-9, 110-10. These calculations are made to assure that the service equipment will clear a fault in case of short circuit. To perform the fault calculations the following information must be obtained: 1. Available Power Company Short circuit KVA at transformer primary : Contact Power Company, may also be given in terms of R + jX. 2. Length of service drop from transformer to building, Type and size of conductor, ie., 250 MCM, aluminum. 3. Impedance of transformer, KVA size. A. %R = Percent Resistance B. %X = Percent Reactance C. %Z = Percent Impedance D. KVA = Kilovoltamp size of transformer. ( Obtain for each transformer if in Bank of 2 or 3) 4. If service entrance consists of several different sizes of conductors, each must be adjusted by (Ohms for 1 conductor) (Number of conductors) This must be done for R and X Three Phase Systems Wye Systems: 120/208V 3∅, 4 wire 277/480V 3∅ 4 wire Delta Systems: 120/240V 3∅, 4 wire 240V 3∅, 3 wire 480 V 3∅, 3 wire Single Phase Systems: Voltage 120/240V 1∅, 3 wire. Separate line to line and line to neutral calculations must be done for single phase systems. Voltage in equations (KV) is the secondary transformer voltage, line to line. Base KVA is 10,000 in all examples. Only those components actually in the system have to be included, each component must have an X and an R value. Neutral size is assumed to be the same size as the phase conductors. -

Operations on Power Series Related to Taylor Series

Operations on Power Series Related to Taylor Series In this problem, we perform elementary operations on Taylor series – term by term differen tiation and integration – to obtain new examples of power series for which we know their sum. Suppose that a function f has a power series representation of the form: 1 2 X n f(x) = a0 + a1(x − c) + a2(x − c) + · · · = an(x − c) n=0 convergent on the interval (c − R; c + R) for some R. The results we use in this example are: • (Differentiation) Given f as above, f 0(x) has a power series expansion obtained by by differ entiating each term in the expansion of f(x): 1 0 X n−1 f (x) = a1 + a2(x − c) + 2a3(x − c) + · · · = nan(x − c) n=1 • (Integration) Given f as above, R f(x) dx has a power series expansion obtained by by inte grating each term in the expansion of f(x): 1 Z a1 a2 X an f(x) dx = C + a (x − c) + (x − c)2 + (x − c)3 + · · · = C + (x − c)n+1 0 2 3 n + 1 n=0 for some constant C depending on the choice of antiderivative of f. Questions: 1. Find a power series representation for the function f(x) = arctan(5x): (Note: arctan x is the inverse function to tan x.) 2. Use power series to approximate Z 1 2 sin(x ) dx 0 (Note: sin(x2) is a function whose antiderivative is not an elementary function.) Solution: 1 For question (1), we know that arctan x has a simple derivative: , which then has a power 1 + x2 1 2 series representation similar to that of , where we subsitute −x for x. -

CONSONANT DIGRAPH- /Ch/ at the Beginning of Words

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION PRIMARY ENGAGEMENT PROGRAMME GRADE FOUR (4) WORKSHEET-TERM 3 SUBJECT: LITERACY WEEK 5: LESSON 1 Name: _______________________________ Date: __________________________ READING: CONSONANT DIGRAPH- /ch/ at the beginning of words FACTS/TIPS A consonant digraph is formed when two consonants work together to make one sound. Consonant digraph ch has three(3) different sounds. 1. /ch/ as in chair, chalk 2. /sh/ as in chef, 3. /k/ as in chaos Let us read these words. Listen to the beginning sound. 1. chalk 2. cheese 3. chip 4. champagne 2. chorus 5. Charmin 6. child 7. chew Read the text below Ms. Charmin and Mr. Philbert work at NAREI. Philbert is a driver and Charmin a clerk. One day our class teacher, Ms. Phillips took us on a field trip where we visited CARICOM, GUYSUCO AND NAREI. Our time spent at NAREI was awesome. We were shown the different departments. One brave pupil, Charlie, asked Ms. Charmin about the meaning of the word 78 NAREI. She told us that the word NAREI is an acronym that means National Agricultural Research and Extension Institute. Ms. Charmin then went on to explain to us the products that are made there. After our tour around the compound, she gave us huge packages of some of the products. We were so excited that we jumped for joy. We took a photograph with her, thanked her and then bid her farewell. On our way back to school we spoke of our day out. We all agreed that it was very informative. ON YOUR OWN Say the words below and listen to the beginning sound. -

Laplace Transform

Chapter 7 Laplace Transform The Laplace transform can be used to solve differential equations. Be- sides being a different and efficient alternative to variation of parame- ters and undetermined coefficients, the Laplace method is particularly advantageous for input terms that are piecewise-defined, periodic or im- pulsive. The direct Laplace transform or the Laplace integral of a function f(t) defined for 0 ≤ t< 1 is the ordinary calculus integration problem 1 f(t)e−stdt; Z0 succinctly denoted L(f(t)) in science and engineering literature. The L{notation recognizes that integration always proceeds over t = 0 to t = 1 and that the integral involves an integrator e−stdt instead of the usual dt. These minor differences distinguish Laplace integrals from the ordinary integrals found on the inside covers of calculus texts. 7.1 Introduction to the Laplace Method The foundation of Laplace theory is Lerch's cancellation law 1 −st 1 −st 0 y(t)e dt = 0 f(t)e dt implies y(t)= f(t); (1) R R or L(y(t)= L(f(t)) implies y(t)= f(t): In differential equation applications, y(t) is the sought-after unknown while f(t) is an explicit expression taken from integral tables. Below, we illustrate Laplace's method by solving the initial value prob- lem y0 = −1; y(0) = 0: The method obtains a relation L(y(t)) = L(−t), whence Lerch's cancel- lation law implies the solution is y(t)= −t. The Laplace method is advertised as a table lookup method, in which the solution y(t) to a differential equation is found by looking up the answer in a special integral table. -

Derivative of Power Series and Complex Exponential

LECTURE 4: DERIVATIVE OF POWER SERIES AND COMPLEX EXPONENTIAL The reason of dealing with power series is that they provide examples of analytic functions. P1 n Theorem 1. If n=0 anz has radius of convergence R > 0; then the function P1 n F (z) = n=0 anz is di®erentiable on S = fz 2 C : jzj < Rg; and the derivative is P1 n¡1 f(z) = n=0 nanz : Proof. (¤) We will show that j F (z+h)¡F (z) ¡ f(z)j ! 0 as h ! 0 (in C), whenever h ¡ ¢ n Pn n k n¡k jzj < R: Using the binomial theorem (z + h) = k=0 k h z we get F (z + h) ¡ F (z) X1 (z + h)n ¡ zn ¡ hnzn¡1 ¡ f(z) = a h n h n=0 µ ¶ X1 a Xn n = n ( hkzn¡k) h k n=0 k=2 µ ¶ X1 Xn n = a h( hk¡2zn¡k) n k n=0 k=2 µ ¶ X1 Xn¡2 n = a h( hjzn¡2¡j) (by putting j = k ¡ 2): n j + 2 n=0 j=0 ¡ n ¢ ¡n¡2¢ By using the easily veri¯able fact that j+2 · n(n ¡ 1) j ; we obtain µ ¶ F (z + h) ¡ F (z) X1 Xn¡2 n ¡ 2 j ¡ f(z)j · jhj n(n ¡ 1)ja j( jhjjjzjn¡2¡j) h n j n=0 j=0 X1 n¡2 = jhj n(n ¡ 1)janj(jzj + jhj) : n=0 P1 n¡2 We already know that the series n=0 n(n ¡ 1)janjjzj converges for jzj < R: Now, for jzj < R and h ! 0 we have jzj + jhj < R eventually. -

Band Radar Models FR-2115-B/2125-B/2155-B*/2135S-B

R BlackBox type (with custom monitor) X/S – band Radar Models FR-2115-B/2125-B/2155-B*/2135S-B I 12, 25 and 50* kW T/R up X-band, 30 kW I Dual-radar/full function remote S-band inter-switching I SXGA PC monitor either CRT or color I New powerful processor with LCD high-speed, high-density gate array and I Optional ARP-26 Automatic Radar sophisticated software Plotting Aid (ARPA) on 40 targets I New cast aluminum scanner gearbox I Furuno's exclusive chart/radar overlay and new series of streamlined radiators technique by optional RP-26 VideoPlotter I Shared monitor utilization of Radar and I Easy to create radar maps PC systems with custom PC monitor switching system The BlackBox radar system FR-2115-B, FR-2125-B, FR-2155-B* and FR-2135S-B are custom configured by adding a user’s favorite display to the blackbox radar package. The package is based on a Furuno standard radar used in the FR-21x5-B series with (FURUNO) monitor which is designed to comply with IMO Res MSC.64(67) Annex 4 for shipborne radar and A.823 (19) for ARPA performance. The display unit may be selected from virtually any size of multi-sync PC monitor, either a CRT screen or flat panel LCD display. The blackbox radar system is suitable for various ships which require no specific type approval as a SOLAS compliant radar. The radar is available in a variety of configurations: 12, 25, 30 and 50* kW output, short or long antenna radiator, 24 or 42 rpm scanner, with standard Electronic Plotting Aid (EPA) and optional Automatic Radar Plotting Aid (ARPA). -

Calculus Terminology

AP Calculus BC Calculus Terminology Absolute Convergence Asymptote Continued Sum Absolute Maximum Average Rate of Change Continuous Function Absolute Minimum Average Value of a Function Continuously Differentiable Function Absolutely Convergent Axis of Rotation Converge Acceleration Boundary Value Problem Converge Absolutely Alternating Series Bounded Function Converge Conditionally Alternating Series Remainder Bounded Sequence Convergence Tests Alternating Series Test Bounds of Integration Convergent Sequence Analytic Methods Calculus Convergent Series Annulus Cartesian Form Critical Number Antiderivative of a Function Cavalieri’s Principle Critical Point Approximation by Differentials Center of Mass Formula Critical Value Arc Length of a Curve Centroid Curly d Area below a Curve Chain Rule Curve Area between Curves Comparison Test Curve Sketching Area of an Ellipse Concave Cusp Area of a Parabolic Segment Concave Down Cylindrical Shell Method Area under a Curve Concave Up Decreasing Function Area Using Parametric Equations Conditional Convergence Definite Integral Area Using Polar Coordinates Constant Term Definite Integral Rules Degenerate Divergent Series Function Operations Del Operator e Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Deleted Neighborhood Ellipsoid GLB Derivative End Behavior Global Maximum Derivative of a Power Series Essential Discontinuity Global Minimum Derivative Rules Explicit Differentiation Golden Spiral Difference Quotient Explicit Function Graphic Methods Differentiable Exponential Decay Greatest Lower Bound Differential -

CHAPTER 3: Derivatives

CHAPTER 3: Derivatives 3.1: Derivatives, Tangent Lines, and Rates of Change 3.2: Derivative Functions and Differentiability 3.3: Techniques of Differentiation 3.4: Derivatives of Trigonometric Functions 3.5: Differentials and Linearization of Functions 3.6: Chain Rule 3.7: Implicit Differentiation 3.8: Related Rates • Derivatives represent slopes of tangent lines and rates of change (such as velocity). • In this chapter, we will define derivatives and derivative functions using limits. • We will develop short cut techniques for finding derivatives. • Tangent lines correspond to local linear approximations of functions. • Implicit differentiation is a technique used in applied related rates problems. (Section 3.1: Derivatives, Tangent Lines, and Rates of Change) 3.1.1 SECTION 3.1: DERIVATIVES, TANGENT LINES, AND RATES OF CHANGE LEARNING OBJECTIVES • Relate difference quotients to slopes of secant lines and average rates of change. • Know, understand, and apply the Limit Definition of the Derivative at a Point. • Relate derivatives to slopes of tangent lines and instantaneous rates of change. • Relate opposite reciprocals of derivatives to slopes of normal lines. PART A: SECANT LINES • For now, assume that f is a polynomial function of x. (We will relax this assumption in Part B.) Assume that a is a constant. • Temporarily fix an arbitrary real value of x. (By “arbitrary,” we mean that any real value will do). Later, instead of thinking of x as a fixed (or single) value, we will think of it as a “moving” or “varying” variable that can take on different values. The secant line to the graph of f on the interval []a, x , where a < x , is the line that passes through the points a, fa and x, fx.