1 the Evolutionary Origin of Bilaterian Smooth and Striated Myocytes 1 2 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Tardigrade Damage Suppressor Protein (Dsup) Expressed in Tobacco

Analysis of Tardigrade Damage Suppressor Protein (Dsup) Expressed in Tobacco by Justin Kirke A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Charles E. Schmidt College of Science In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL December 2019 Copyright 2019 by Justin Kirke ii Abstract Author: Justin Kirke Title: Analysis of Tardigrade Damage Suppressor Protein (Dsup) Expressed in Tobacco Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. Xing-Hai Zhang Degree: Master of Science Year: 2019 DNA damage is one of the most harmful stress inducers in living organisms. Studies have shown that exposure to high doses of various types of radiation cause DNA sequence changes (mutation) and disturb protein synthesis, hormone balance, leaf gas exchange and enzyme activity. Recent discovery of a protein called Damage Suppressor Protein (Dsup), found in the tardigrade species Ramazzotius varieornatus, has shown to reduce the effects of radiation damage in human cell lines. We have generated multiple lines of tobacco plants expressing the Dsup gene and preformed numerous tests to show viability and response of these transgenic plants when exposed to mutagenic chemicals, UV radiation and ionizing radiation. We have also investigated Dsup function in association to DNA damage and repair in plants by analyzing the expression of related genes using RT-qPCR. We have also analyzed DNA damage from X-ray and UV treatments using an Alkaline Comet Assay. This project has the potential to help generate plants that are tolerant to more extreme stress environments, particularly DNA damage and iv mutation, unshielded by our atmosphere. -

Diapause in Tardigrades: a Study of Factors Involved in Encystment

2296 The Journal of Experimental Biology 211, 2296-2302 Published by The Company of Biologists 2008 doi:10.1242/jeb.015131 Diapause in tardigrades: a study of factors involved in encystment Roberto Guidetti1,*, Deborah Boschini2, Tiziana Altiero2, Roberto Bertolani2 and Lorena Rebecchi2 1Department of the Museum of Paleobiology and Botanical Garden, Via Università 4, 41100, Modena, Italy and 2Department of Animal Biology, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Via Campi 213/D, 41100, Modena, Italy *Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) Accepted 12 May 2008 SUMMARY Stressful environmental conditions limit survival, growth and reproduction, or these conditions induce resting stages indicated as dormancy. Tardigrades represent one of the few animal phyla able to perform both forms of dormancy: quiescence and diapause. Different forms of cryptobiosis (quiescence) are widespread and well studied, while little attention has been devoted to the adaptive meaning of encystment (diapause). Our goal was to determine the environmental factors and token stimuli involved in the encystment process of tardigrades. The eutardigrade Amphibolus volubilis, a species able to produce two types of cyst (type 1 and type 2), was considered. Laboratory experiments and long-term studies on cyst dynamics of a natural population were conducted. Laboratory experiments demonstrated that active tardigrades collected in April produced mainly type 2 cysts, whereas animals collected in November produced mainly type 1 cysts, indicating that the different responses are functions of the physiological state at the time they were collected. The dynamics of the two types of cyst show opposite seasonal trends: type 2 cysts are present only during the warm season and type 1 cysts are present during the cold season. -

Mitochondrial Genomes of Two Polydora

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Mitochondrial genomes of two Polydora (Spionidae) species provide further evidence that mitochondrial architecture in the Sedentaria (Annelida) is not conserved Lingtong Ye1*, Tuo Yao1, Jie Lu1, Jingzhe Jiang1 & Changming Bai2 Contrary to the early evidence, which indicated that the mitochondrial architecture in one of the two major annelida clades, Sedentaria, is relatively conserved, a handful of relatively recent studies found evidence that some species exhibit elevated rates of mitochondrial architecture evolution. We sequenced complete mitogenomes belonging to two congeneric shell-boring Spionidae species that cause considerable economic losses in the commercial marine mollusk aquaculture: Polydora brevipalpa and Polydora websteri. The two mitogenomes exhibited very similar architecture. In comparison to other sedentarians, they exhibited some standard features, including all genes encoded on the same strand, uncommon but not unique duplicated trnM gene, as well as a number of unique features. Their comparatively large size (17,673 bp) can be attributed to four non-coding regions larger than 500 bp. We identifed an unusually large (putative) overlap of 14 bases between nad2 and cox1 genes in both species. Importantly, the two species exhibited completely rearranged gene orders in comparison to all other available mitogenomes. Along with Serpulidae and Sabellidae, Polydora is the third identifed sedentarian lineage that exhibits disproportionally elevated rates of mitogenomic architecture rearrangements. Selection analyses indicate that these three lineages also exhibited relaxed purifying selection pressures. Abbreviations NCR Non-coding region PCG Protein-coding gene Metazoan mitochondrial genomes (mitogenomes) usually encode the set of 37 genes, comprising 2 rRNAs, 22 tRNAs, and 13 proteins, encoded on both genomic strands. -

Animal Phylum Poster Porifera

Phylum PORIFERA CNIDARIA PLATYHELMINTHES ANNELIDA MOLLUSCA ECHINODERMATA ARTHROPODA CHORDATA Hexactinellida -- glass (siliceous) Anthozoa -- corals and sea Turbellaria -- free-living or symbiotic Polychaetes -- segmented Gastopods -- snails and slugs Asteroidea -- starfish Trilobitomorpha -- tribolites (extinct) Urochordata -- tunicates Groups sponges anemones flatworms (Dugusia) bristleworms Bivalves -- clams, scallops, mussels Echinoidea -- sea urchins, sand Chelicerata Cephalochordata -- lancelets (organisms studied in detail in Demospongia -- spongin or Hydrazoa -- hydras, some corals Trematoda -- flukes (parasitic) Oligochaetes -- earthworms (Lumbricus) Cephalopods -- squid, octopus, dollars Arachnida -- spiders, scorpions Mixini -- hagfish siliceous sponges Xiphosura -- horseshoe crabs Bio1AL are underlined) Cubozoa -- box jellyfish, sea wasps Cestoda -- tapeworms (parasitic) Hirudinea -- leeches nautilus Holothuroidea -- sea cucumbers Petromyzontida -- lamprey Mandibulata Calcarea -- calcareous sponges Scyphozoa -- jellyfish, sea nettles Monogenea -- parasitic flatworms Polyplacophora -- chitons Ophiuroidea -- brittle stars Chondrichtyes -- sharks, skates Crustacea -- crustaceans (shrimp, crayfish Scleropongiae -- coralline or Crinoidea -- sea lily, feather stars Actinipterygia -- ray-finned fish tropical reef sponges Hexapoda -- insects (cockroach, fruit fly) Sarcopterygia -- lobed-finned fish Myriapoda Amphibia (frog, newt) Chilopoda -- centipedes Diplopoda -- millipedes Reptilia (snake, turtle) Aves (chicken, hummingbird) Mammalia -

Introduction to the Body-Plan of Onychophora and Tardigrada

Joakim Eriksson, 02.12.13 Animal bodyplans Onychophora Tardigrada Bauplan, bodyplan • A Bauplan is a set of conservative characters that are typical for one group but distinctively different from a Bauplan of another group Arthropoda Bauplan 2 Bauplan 3 Bauplan 4 Tardigrada Onychophora Euarthropoda/Arthropoda Insects Chelicerates Myriapods Crustaceans Arthropoda/Panarthropoda Bauplan 1 Arthropod characters • Body segmented, with limbs on several segments • Adult body cavity a haemocoel that extends into the limbs • Cuticle of α-chitin which is molted regularly • Appendages with chitinous claws, and mixocoel with metanephridia and ostiate heart (absent in tardigrades) • Engrailed gene expressed in posterior ectoderm of each segment • Primitively possess a terminal mouth, a non-retractable proboscis, and a thick integument of diverse plates Phylogenomics and miRNAs suggest velvets worm are the sister group to the arthropods within a monophyletic Panarthropoda. Campbell L I et al. PNAS 2011;108:15920-15924 Fossil arthropods, the Cambrian explosion Aysheaia An onychophoran or phylum of its own? Anomalocaris A phylum on its own? Crown group and stem group Arthropoda Bauplan 2 Bauplan 3 Bauplan 4 Tardigrada Onychophora Euarthropoda/Arthropoda Arthropoda/Panarthropoda Bauplan 1 How do arthropods relate to other animal groups Articulata Georges Cuvier, 1817 Characters uniting articulata: •Segmentation •Ventral nerv cord •Teloblastic growth zone Ecdysozoa Aguinaldo et al 1997 Ecdysozoa Character uniting ecdysozoa: •Body covered by cuticle of α-chitin -

The Impact of Tourists on Antarctic Tardigrades: an Ordination-Based Model

J. Limnol., 2013; 72(s1): 128-135 DOI: 10.4081/jlimnol.2013.s1.e16 The impact of tourists on Antarctic tardigrades: an ordination-based model Sandra J. McINNES,1* Philip J.A. PUGH2 1British Antarctic Survey, Natural Environment Research Council, High Cross, Madingley Road, Cambridge, CB3 0ET, UK; 2Department of Life Sciences, Anglia Ruskin University, East Road, Cambridge, CB1 1PT, UK *Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT Tardigrades are important members of the Antarctic biota yet little is known about their role in the soil fauna or whether they are affected by anthropogenic factors. The German Federal Environment Agency commissioned research to assess the impact of human activities on soil meiofauna at 14 localities along the Antarctic peninsula during the 2009/2010 and 2010/2011 austral summers. We used ordination techniques to re-assess the block-sampling design used to compare areas of high and low human impact, to identify which of the sampled variables were biologically relevant and/or demonstrated an anthropogenic significance. We found the most sig- nificant differences between locations, reflecting local habitat and vegetation factor, rather than within-location anthropogenic impact. We noted no evidence of exotic imports but report on new maritime Antarctic sample sites and habitatsonly. Key words: Tardigrada, soil, alien introduction, maritime Antarctic. INTRODUCTION The German Federal Environment Agency commis- sioned a studyuse into the impact of ship-based tourism on The introduction of exotic taxa is regarded as a major Antarctic terrestrial soil ecosystems, focusing on a range threat to native species even in Antarctica (Chown et al., of taxa including Tardigrada. -

Phylum Onychophora

Lab exercise 6: Arthropoda General Zoology Laborarory . Matt Nelson phylum onychophora Velvet worms Once considered to represent a transitional form between annelids and arthropods, the Onychophora (velvet worms) are now generally considered to be sister to the Arthropoda, and are included in chordata the clade Panarthropoda. They are no hemichordata longer considered to be closely related to echinodermata the Annelida. Molecular evidence strongly deuterostomia supports the clade Panarthropoda, platyhelminthes indicating that those characteristics which the velvet worms share with segmented rotifera worms (e.g. unjointed limbs and acanthocephala metanephridia) must be plesiomorphies. lophotrochozoa nemertea mollusca Onychophorans share many annelida synapomorphies with arthropods. Like arthropods, velvet worms possess a chitinous bilateria protostomia exoskeleton that necessitates molting. The nemata ecdysozoa also possess a tracheal system similar to that nematomorpha of insects and myriapods. Onychophorans panarthropoda have an open circulatory system with tardigrada hemocoels and a ventral heart. As in arthropoda arthropods, the fluid-filled hemocoel is the onychophora main body cavity. However, unlike the arthropods, the hemocoel of onychophorans is used as a hydrostatic acoela skeleton. Onychophorans feed mostly on small invertebrates such as insects. These prey items are captured using a special “slime” which is secreted from large slime glands inside the body and expelled through two oral papillae on either side of the mouth. This slime is protein based, sticking to the cuticle of insects, but not to the cuticle of the velvet worm itself. Secreted as a liquid, the slime quickly becomes solid when exposed to air. Once a prey item is captured, an onychophoran feeds much like a spider. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter ^ce, while others may t>e from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will t>e noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to t>e removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, t>eginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in ttie original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black arxt white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI* Phylogeny of Vestimentiferan Tube Worms by Anja Schulze Diplom, University of Bielefeld, 1995 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Biology We accept this dissertation as conforming to the required standard Dr. -

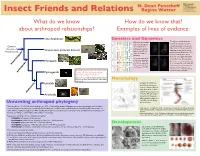

(Includes Insects) Myriapods Pycnogonids Limulids Arachnids

N. Dean Pentcheff Insect Friends and Relations Regina Wetzer What do we know How do we know that? about arthropod relationships? Examples of lines of evidence: Onychophorans Genetics and Genomics Genomic approaches The figures at left show the can look at patterns protein structure of opsins Common of occurrence of (visual pigments). Yellow iden- tifies areas of the protein that Ancestor of whole genes across Crustaceans (includes Insects) have important evolutionary Panarthropoda taxa to identify pat- terns of common and functional differences. This ancestry. provides information about how the opsin gene family has Cook, C. E., Smith, M. L., evolved across different taxa. Telford, M. J., Bastianello, Myriapods A., Akam, M. 2001. Hox Porter, M. L., Cronin, T. W., McClellan, Panarthropoda genes and the phylogeny D. A., Crandall, K. A. 2007. Molecular of the arthropods. Cur- characterization of crustacean visual rent Biology 11: 759-763. pigments and the evolution of pan- crustacean opsins. Molecular Biology This phylogenetic tree of the Arthropoda and Evolution 24(1): 253-268. Arthropoda Pycnogonids outlines our best current knowledge about relationships in the group. Dunn, C.W. et al. 2008. Broad phylogenetic sampling improves resolution of the animal tree of life. Nature Morphology 452: 745-749. Limulids Comparing similarities and differences among arthropod appendages is a fertile source of infor- Chelicerata mation about patterns of ancestry. Morphological Arachnids evidence can be espec- ially valuable because it is available for both living Unraveling arthropod phylogeny and fossil taxa. There are about 1,100,000 described arthropods – 85% of multicellular animals! Segmentation, jointed appendages, and the devel- opment of pattern-forming genes profoundly affected arthropod evolution and created the most morphologically diverse taxon on [Left:] Cotton, T. -

Cell Proliferation Pattern and Twist Expression in an Aplacophoran

RESEARCH ARTICLE Cell Proliferation Pattern and Twist Expression in an Aplacophoran Mollusk Argue Against Segmented Ancestry of Mollusca EMANUEL REDL1, MAIK SCHERHOLZ1, TIM WOLLESEN1, CHRISTIANE TODT2, 1∗ AND ANDREAS WANNINGER 1Faculty of Life Sciences, Department of Integrative Zoology, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria 2University Museum, The Natural History Collections, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway ABSTRACT The study of aplacophoran mollusks (i.e., Solenogastres or Neomeniomorpha and Caudofoveata or Chaetodermomorpha) has traditionally been regarded as crucial for reconstructing the morpho- logy of the last common ancestor of the Mollusca. Since their proposed close relatives, the Poly- placophora, show a distinct seriality in certain organ systems, the aplacophorans are also in the focus of attention with regard to the question of a potential segmented ancestry of mollusks. To contribute to this question, we investigated cell proliferation patterns and the expression of the twist ortholog during larval development in solenogasters. In advanced to late larvae, during the outgrowth of the trunk, a pair of longitudinal bands of proliferating cells is found subepithelially in a lateral to ventrolateral position. These bands elongate during subsequent development as the trunk grows longer. Likewise, expression of twist occurs in two laterally positioned, subepithelial longitudinal stripes in advanced larvae. Both, the pattern of proliferating cells and the expression domain of twist demonstrate the existence of extensive and long-lived mesodermal bands in a worm-shaped aculiferan, a situation which is similar to annelids but in stark contrast to conchifer- ans, where the mesodermal bands are usually rudimentary and ephemeral. Yet, in contrast to annelids, neither the bands of proliferating cells nor the twist expression domain show a sepa- ration into distinct serial subunits, which clearly argues against a segmented ancestry of mollusks. -

Placozoans Are Eumetazoans Related to Cnidaria

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/200972; this version posted October 11, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. 1 Placozoans are eumetazoans related to Cnidaria Christopher E. Laumer1,2, Harald Gruber-Vodicka3, Michael G. Hadfield4, Vicki B. Pearse5, Ana Riesgo6, 4 John C. Marioni1,2,7, and Gonzalo Giribet8 1. Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Hinxton, CB10 1SA, United Kingdom 2. European Molecular Biology Laboratories-European Bioinformatics Institute, Hinxton, CB10 1SD, United Kingdom 8 3. Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Celsiusstraβe 1, D-28359 Bremen, Germany 4. Kewalo Marine Laboratory, Pacific Biosciences Research Center/University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, 41 Ahui Street, Honolulu, HI 96813, United States of America 5. University of California, Santa Cruz, Institute of Marine Sciences, 1156 High Street, Santa 12 Cruz, CA 95064, United States of America 6. The Natural History Museum, Life Sciences, Invertebrate Division Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, United Kingdom 7. Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute, University of Cambridge, Li Ka Shing Centre, 16 Robinson Way, Cambridge CB2 0RE, United Kingdom 8. Museum of Comparative Zoology, Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, 26 Oxford Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, United States of America 20 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/200972; this version posted October 11, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Development of a Lecithotrophic Pilidium Larva Illustrates Convergent Evolution of Trochophore-Like Morphology Marie K

Hunt and Maslakova Frontiers in Zoology (2017) 14:7 DOI 10.1186/s12983-017-0189-x RESEARCH Open Access Development of a lecithotrophic pilidium larva illustrates convergent evolution of trochophore-like morphology Marie K. Hunt and Svetlana A. Maslakova* Abstract Background: The pilidium larva is an idiosyncrasy defining one clade of marine invertebrates, the Pilidiophora (Nemertea, Spiralia). Uniquely, in pilidial development, the juvenile worm forms from a series of isolated rudiments called imaginal discs, then erupts through and devours the larval body during catastrophic metamorphosis. A typical pilidium is planktotrophic and looks like a hat with earflaps, but pilidial diversity is much broader and includes several types of non-feeding pilidia. One of the most intriguing recently discovered types is the lecithotrophic pilidium nielseni of an undescribed species, Micrura sp. “dark” (Lineidae, Heteronemertea, Pilidiophora). The egg-shaped pilidium nielseni bears two transverse circumferential ciliary bands evoking the prototroch and telotroch of the trochophore larva found in some other spiralian phyla (e.g. annelids), but undergoes catastrophic metamorphosis similar to that of other pilidia. While it is clear that the resemblance to the trochophore is convergent, it is not clear how pilidium nielseni acquired this striking morphological similarity. Results: Here, using light and confocal microscopy, we describe the development of pilidium nielseni from fertilization to metamorphosis, and demonstrate that fundamental aspects of pilidial development are conserved. The juvenile forms via three pairs of imaginal discs and two unpaired rudiments inside a distinct larval epidermis, which is devoured by the juvenile during rapid metamorphosis. Pilidium nielseni even develops transient, reduced lobes and lappets in early stages, re-creating the hat-like appearance of a typical pilidium.