The Portsmouth Spartans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Retreat Date Advanced to Jan. 30 DEEDED to BOARD -H- by the EDITOR of USF TRUSTEES HAPPY NEW YEAR

Council Dance Hear Holloway Tomorrow Monday At Fairmont Room D2 VOL. X—No. 2 SAX FRANCISCO, JANUARY 19, 1934 FRIDAY TITLE D TO FUTURE USF SITE • K CEMETERY LANDS Annual Retreat Date Advanced to Jan. 30 DEEDED TO BOARD -H- By THE EDITOR OF USF TRUSTEES HAPPY NEW YEAR. Best news O'Toole Collides HOLLOWAY TO GIVE Battle On Casaba Courts Near of the year is the signing of the docu DEVOTIONS TO BE ments which will finally affect the With Car In Dash Gigantic Program Nearing transfer of the cemetery properties HELD IN COLLEGE RADIO TALK JAN. 22 As Juniors Challenge Seniors to the university. The papers were Completion After To Morning Class Two Years signed on New Year's Eve. Some IN K.AJ\LECTURE Rancour still rankling after the down the greensward all that long thing of prophecy or symbolism in CHURCHON 3 DAYS zero to nothing tie result of the and cold afternoon, no decision could that. Mayhap it was more than the A few minutes to eight o'clock dash ended in bruises and contusions senior-junior football battle last fall, be reached. The slightly stronger 'INVEST IN YOUTH' birth of 1934. After having success Commercial Side of Radio the junior class president, Leo junior offense broke itself against the fully weathered the worst blows of Reverend James Henry Will for Tom O'Toole, '36, as he collided with a moving automobile on Twenty- To Be Subject of Murphy, threw down the gauntlet to stubborn senior defence. Fraction of Purchase Price the depression, the old ship USF Conduct Spiritual Bernard Wiesinger, senior class Each class claimed at least a may be headed for the smoother sail first street last Tuesday morning. -

Eastern Progress Eastern Progress 1963-1964

Eastern Progress Eastern Progress 1963-1964 Eastern Kentucky University Year 1963 Eastern Progress - 22 Nov 1963 Eastern Kentucky University This paper is posted at Encompass. http://encompass.eku.edu/progress 1963-64/10 ■ Thanksgiving Little Theatre History Mixes Work, Fun Pufee 3 Pufee 2 OGR&SS 'Setting The Pace In A Progressive Era Student Publication of Eastern St^te College, Richmo nd, Kentucky 41 st Year No. 10 Friday, November 22, 1963 Coliseum Dedication Presnell Resigns As Head Coach Game December 4 Against Louisville Roy Kidd Named As Successor By ELLEN RICE state plan to attend the dedica- Former Maroon Takes Athletic Progress NCMW Editor tory game. mod " Previously games were play- JIM PARKS ed in the Weaver Health Build- All American Director Post Progress Sports Editor ing gymnasium. The last Glenn Presnell announced game played there was against -Roy Kidd, former Little All- The Alumni Coliseum will be America . quarterback here his resignation as football dedicated as a basketball ' Louisville on March 6 last coach Tuesday to become ath- spring. The Cardinals won was named head football arena at the Louisville-Eest- coach at his alma mater Wed- letic director. am basketball, game on Wed- 96-78. The Weaver Health gym nesday, succeeding Glenn Pres- His resignation will become nesday, December 4. nell, who resigned Tuesday to effective following tomorrow's The game will be the first served as home of the Maroons for 32 years and saw 265 var- become athletic director. closing football game against in the new structure which Is Youngstown University at dedicated to the almost 12,000 sity tilts played there. -

Nagurski's Debut and Rockne's Lesson

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 20, No. 3 (1998) NAGURSKI’S DEBUT AND ROCKNE’S LESSON Pro Football in 1930 By Bob Carroll For years it was said that George Halas and Dutch Sternaman, the Chicago Bears’ co-owners and co- coaches, always took opposite sides in every minor argument at league meetings but presented a united front whenever anything major was on the table. But, by 1929, their bickering had spread from league politics to how their own team was to be directed. The absence of a united front between its leaders split the team. The result was the worst year in the Bears’ short history -- 4-9-2, underscored by a humiliating 40-6 loss to the crosstown Cardinals. A change was necessary. Neither Halas nor Sternaman was willing to let the other take charge, and so, in the best tradition of Solomon, they resolved their differences by agreeing that neither would coach the team. In effect, they fired themselves, vowing to attend to their front office knitting. A few years later, Sternaman would sell his interest to Halas and leave pro football for good. Halas would go on and on. Halas and Sternaman chose Ralph Jones, the head man at Lake Forest (IL) Academy, as the Bears’ new coach. Jones had faith in the T-formation, the attack mode the Bears had used since they began as the Decatur Staleys. While other pro teams lined up in more modern formations like the single wing, double wing, or Notre Dame box, the Bears under Jones continued to use their basic T. -

Statistical Leaders of the ‘20S

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 14, No. 2 (1992) Statistical Leaders of the ‘20s By Bob GIll Probably the most ambitious undertaking in football research was David Neft’s effort to re-create statistics from contemporary newspaper accounts for 1920-31, the years before the NFL started to keep its own records. Though in a sense the attempt had to fail, since complete and official stats are impossible, the results of his tireless work provide the best picture yet of the NFL’s formative years. Since the stats Neft obtained are far from complete, except for scoring records, he refrained from printing yearly leaders for 1920-31. But it seems a shame not to have such a list, incomplete though it may be. Of course, it’s tough to pinpoint a single leader each year; so what follows is my tabulation of the top five, or thereabouts, in passing, rushing and receiving for each season, based on the best information available – the stats printed in Pro Football: The Early Years and Neft’s new hardback edition, The Football Encyclopedia. These stats can be misleading, because one man’s yardage total will be based on, say, five complete games and four incomplete, while another’s might cover just 10 incomplete games (i.e., games for which no play-by-play accounts were found). And then some teams, like Rock Island, Green Bay, Pottsville and Staten Island, often have complete stats, based on play-by-plays for every game of a season. I’ll try to mention variations like that in discussing each year’s leaders – for one thing, “complete” totals will be printed in boldface. -

Mcafee Takes a Handoff from Sid Luckman (1947)

by Jim Ridgeway George McAfee takes a handoff from Sid Luckman (1947). Ironton, a small city in Southern Ohio, is known throughout the state for its high school football program. Coach Bob Lutz, head coach at Ironton High School since 1972, has won more football games than any coach in Ohio high school history. Ironton High School has been a regular in the state football playoffs since the tournament’s inception in 1972, with the school winning state titles in 1979 and 1989. Long before the hiring of Bob Lutz and the outstanding title teams of 1979 and 1989, Ironton High School fielded what might have been the greatest gridiron squad in school history. This nearly-forgotten Tiger squad was coached by a man who would become an assistant coach with the Cleveland Browns, general manager of the Buffalo Bills and the second director of the Pro Football Hall of Fame. The squad featured three brothers, two of which would become NFL players, in its starting eleven. One of the brothers would earn All-Ohio, All-American and All-Pro honors before his enshrinement in Canton, Ohio. This story is a tribute to the greatest player in Ironton High School football history, his family, his high school coach and the 1935 Ironton High School gridiron squad. This year marks the 75th anniversary of the undefeated and untied Ironton High School football team featuring three players with the last name of McAfee. It was Ironton High School’s first perfect football season, and the school would not see another such gridiron season until 1978. -

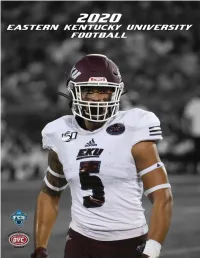

2020 EKU Football Record Book.Indd

2017 EKU Football Record Book 1 @EKUSports Football 2020 Roster ALPHABETICAL ROSTER NUMERICAL ROSTER No. Name Pos. No. Player Pos. Ht. Wt. Cl. Hometown (Previous School) 84 Reece Adkins TE 0 Tahj McClung DL 6-2 320 Jr. Louisville, Ky. (Duke University) 95 Abe Alabi DT 1 Kaymen Cureton QB 6-0 205 R-Jr. Lawndale, Calif. (University of Nevada, Reno) 13 Dakota Allen QB 2 Craig Sinclair Jr. DB 5-11 165 Fr. Jacksonville, Fla. (Bartram Trail HS) 22 Jaylyn Allen LB 3 Jacquez Jones WR 5-10 169 R-Jr. Clearwater, Fla. (University of Tennessee) 14 Je’Vari Anderson LB 4 Kyeandre Magloire RB 6-0 200 Fr. Minneola, Fla. (Lake Minneola HS) Dez Andrews-Ogbogu DB 5 TJ Comstock DB 5-11 195 R-Sr. Louisville, Ky. (duPont Manual HS) 75 Christopher Anthony OL 6 Matt Wilcox Jr. WR 5-10 185 Sr. Dayton, Ohio (Independence CC) 7 Madison Norris LB 6-5 214 R-So. Indianapolis, Ind. (Indiana University) 83 Khalil Arnold TE 8 Thomas Cook P 5-9 193 R-Sr. Moore, S.C. (Limestone University) 76 Tex Bailey OL 8 Jaden Woods DB 6-0 180 So. Decatur, Ga. (South Gwinnett HS) Greg Bain WR 9 Jairus Brents CB 5-9 185 R-So. Louisville, Ky. (University of Louisville) 91 Darrian Baker DL 10 Davion Ross DB 5-10 165 So. Perry, Ga. (Perry HS) 71 Jackson Bardall OL 11 Joseph Sayles DB 6-0 187 Jr. Alpharetta, Ga. (Chattahoochee HS) 35 Ethan Bednarczyk WR 12 Josh Hayes DB 6-0 185 R-Sr. -

Nebraska All-Conference Selections 1916-- H.H

Nebraska All-Conference Selections 1916-- H.H. Corey, tackle 1935-- Bernard Scherer, end 514 total (2) Hugo Otopalik, back (5) Fred Shirey, tackle Big Eight (261) First-team all-conference picks by wire services, 1959-- Don Olson, guard 1917-- Roscoe Rhodes, end Lloyd Cardwell, back Omaha World-Herald, conference coaches. 1960-- Don Purcell, end (5) Edson Shaw, tackle Jerry LaNoue, back 1961-- Bill Thornton, back E.H. Schellenberg, back Sam Francis, back 1962-- Dennis Claridge, back John Cook, back 1936-- Charles Brock, center Husker Four-Time (3) Tyrone Robertson, tackle Paul Dobson, back (6) Les McDonald, end Bob Brown, guard All-Conference Selections 1921-- Clarence Swanson, end Fred Shirey, tackle 1963-- Dennis Claridge, back Tom Novak, back 1946, (4) John Pucelik, guard Lloyd Cardwell, back (3) Lloyd Voss, tackle center 1947-48-49 Glen Preston, back Sam Francis, back Bob Brown, guard Chick Hartley, back Ron Douglas, back 1964-- Lyle Sittler, C 1922-- Leo Scherer, end 1937-- Charles Brock, center (7) Tony Jeter, TE Husker Three-Time (7) Bub Weller, tackle (6) Elmer Dohrmann, end Freeman White, SE Adolph Wenke, tackle Johnny Howell, back All-Conference Picks Ted Vactor, DB Joy Berquist, guard Ted Doyle, tackle Vic Halligan, back, 1912-13-14 Walt Barnes, MG Glen Preston, back Fred Shirey, tackle Dick Rutherford, back, 1913-14-15 Kent McCloughan, DB Dave Noble, back Bob Mehring, guard H.H. Corey, tackle, 1914-15-16 Larry Kramer, tackle Chick Hartley, back 1938-- Charles Brock, center Steve Hokuf, end, 1929-30-32 1965-- Frank Solich, -

1927-12-02 17 09.Pdf (5.624Mb)

LC© The Technique 4 4 T H E SOUTH'S LIVEST COLLEGE WEEKLY" Georgia School of Technology VOL. XVII THE TECHNIQUE, ATLANTA, GA ., FRIDAY, DECEMBER 2, 1927 No. IX TECH BATTLES GEORGIA Captain Crowley, Alternate Captain Hood, and the Jacket Squad who will face the Bulldogs tomorrow Alumni Gather For Jacket Squad Loses Jackets and Bulldogs Five By Graduation I Homecoming Game Prospects Good For 1928 Primed For Thriller I CLASS OF '07 WILL HOLD BANQUET When the Baby Jackets took the SOUTHERN CHAMPIONSHIP AT STAKE field against the Georgia Freshmen, ORE than forty thousand rabid football fans will be thrown T> OYAL entertainment is provided for the "Old Grads" when the Tech Freshmen had the Southern into a frenzy when Georgia Tech and the University of Geor X\ they pour into Atlanta today and tomorrow for the big game championship in sight. In defeating M gia meet here Saturday afternoon on Grant Field for the and for the annual homecoming. Alumni will be present from the Bullpups so overwhelmingly, they southern football championship. When Director Frank Roman Denver, Colorado, New York City, and other distant places, and it cinched the title for the second time starts up his Tech band with "Ramblin' Wreck" and the strains of is expected that last year's record of four hundred alumni in at within three years. Last year they tendance will be broken. "Glory, Glory to Old Georgia" fill the air those shouting, scream were runner-up to the Florida Frosh, ing and cheering forty thousand will form the background to one The festivities will begin on Friday while the year before they won the night, December 2nd, when the class of the most thrilling encounters on the gridiron this season. -

2018 Texas Longhorns Football Media Guide

2018 TEXAS LONGHORNS FOOTBALL MEDIA GUIDE #THISISTEXAS 83 OUTLOOK PLAYERS COACHES 2017 STATS HISTORY RECORDS 2018 TEXAS LONGHORNS FOOTBALL MEDIA GUIDE HISTORY OF THE HEISMAN TROPHY YEAR WINNER SCHOOL POS YEAR WINNER SCHOOL POS YEAR WINNER SCHOOL POS 2017 Baker Mayfield Oklahoma QB 1989 Andre Ware Houston QB 1961 Ernie Davis Syracuse HB 2016 Lamar Jackson Louisville QB 1988 Barry Sanders Oklahoma State TB 1960 Joe Bellino Navy HB 2015 Derrick Henry Alabama RB 1987 Tim Brown Notre Dame WR 1959 Billy Cannon LSU HB 2014 Marcus Mariota Oregon QB 1986 Vinny Testaverde Miami (Fla.) QB 1958 Pete Dawkins Army HB 2013 Jameis Winston Florida State QB 1985 Bo Jackson Auburn TB 1957 John David Crow Texas A&M RB 2012 Johnny Manziel Texas A&M QB 1984 Doug Flutie Boston College QB 1956 Paul Hornung Notre Dame QB 2011 Robert Griffin III Baylor QB 1983 Mike Rozier Nebraska RB 1955 Howard Cassady Ohio State HB 2010 Cameron Newton Auburn QB 1982 Herschel Walker Georgia TB 1954 Alan Ameche Wisconsin FB 2009 Mark Ingram Alabama RB 1981 Marcus Allen USC TB 1953 John Lattner Notre Dame HB 2008 Sam Bradford Oklahoma QB 1980 George Rogers South Carolina RB 1952 Billy Vessels Oklahoma HB 2007 Tim Tebow Florida QB 1979 Charles White USC TB 1951 Dick Kazmaier Princeton RB 2006 Troy Smith Ohio State QB 1978 Billy Simms Oklahoma HB 1950 Vic Janowicz Ohio State HB 2005 Reggie Bush USC RB 1977 EARL CAMPBELL TEXAS RB 1949 Leon Hart Notre Dame End 2004 Matt Leinart USC QB 1976 Tony Dorsett Pittsburgh RB 1948 Doak Walker SMU RB 2003 Jason White Oklahoma QB 1975 Archie Griffin -

UA19/17/1/4 Football Program - WKU Vs Eastern Kentucky University WKU Athletic Media Relations

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® WKU Archives Records WKU Archives 10-20-1956 UA19/17/1/4 Football Program - WKU vs Eastern Kentucky University WKU Athletic Media Relations Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/dlsc_ua_records Recommended Citation WKU Athletic Media Relations, "UA19/17/1/4 Football Program - WKU vs Eastern Kentucky University" (1956). WKU Archives Records. Paper 767. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/dlsc_ua_records/767 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in WKU Archives Records by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 50th ANNIVERSARY HOMECOMING . ~ WESTERN .' EASTERN • \or .- . AGAIN - ALL WESTERN FOOTBALL AND BASKETBALL GAMES BROADCAST OVER ASHLAND-AETNA SPORTS NETWORK ORIGINATED BY 5000 Watts WLBJ 1410 K. c. First In Bowling Green The Most Powerful Radio Station In Southern And Western Kentucky BOWLING GREEN BANK And TRUST CO. AUTO STORES. INC. KELLEY WITHERSPOON Complete Banking - Trust Service "It' .~ Easy To Pay Bill's Friendly Way" Phone VI 3-4348 - VI 3-4349 332 E. Main St. Phone VI 3-5553 GOOD LUCK, HILLTOPPERS , Morris Jewelry ELITE DRY CLEAN ERS "Bowling Green's Oldest & Best Jewelers" ELITE SELF SERVICE LAUNDRY 224 E. 12th St. We Deliver A Complete Line of National Stores Shoes For Every Member of The Family "Two Stores on the Square" Miracle Tread Store No.1 - 427-429 Park Row American Gentlemen Store No. 2 - 907 College St. Fa m i Iy Shoe Store Bowling Green, Ky. Dodson Clothes Bldg. For Driving Thrills Drive Hilda-Toppers BUICK Russellville Road specializing in Harry Lea~hman Bui~k, In~. -

Hall of Very Good Class of 2013

Professional Football Researchers Association 740 Deerfield Road Warminster, PA 18974 www.profootballresearchers.org Media contact: Ken Crippen (215) 421-6994 [email protected] PFRA ANNOUNCES THE HALL OF VERY GOOD CLASS OF 2013 WARMINSTER, Pennsylvania (June 3, 2013) – The Professional Football Researchers Association (PFRA) announced today the Hall of Very Good Class of 2013. The inductees are (in alphabetical order): Erich Barnes Position: Defensive Back Teams: 1958-60 Chicago Bears, 1961-64 New York Giants, 1965-71 Cleveland Browns Mike Curtis Position: Linebacker Teams: 1965-75 Baltimore Colts, 1976 Seattle Seahawks, 1977-78 Washington Redskins Roman Gabriel Position: Quarterback Teams: 1962-72 Los Angeles Rams, 1973-77 Philadelphia Eagles Cookie Gilchrist Position: Fullback Teams: 1962-64 Buffalo Bills, 1965 Denver Broncos, 1966 Miami Dolphins, 1967 Denver Broncos Bob Kuechenberg Position: Guard-Tackle Teams: 1970-83 Miami Dolphins The Professional Football Researchers Association (PFRA) is a nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving and, in some cases, reconstructing professional football history. The PFRA is incorporated in the state of Connecticut and has 501(c)(3) status as an educational organization with the Internal Revenue Service. Professional Football Researchers Association 740 Deerfield Road Warminster, PA 18974 www.profootballresearchers.org Daryle Lamonica Position: Quarterback Teams: 1963-66 Buffalo Bills, 1967-74 Oakland Raiders Lemar Parrish Position: Defensive Back Teams: 1970-77 Cincinnati Bengals, 1978-81 Washington Redskins, 1982 Buffalo Bills Donnie Shell Position: Defensive Back Teams: 1974-87 Pittsburgh Steelers Jim Tyrer Position: Tackle Teams: 1961-73 Dallas Texans/Kansas City Chiefs, 1974 Washington Redskins Begun in 2003, the Hall of Very Good seeks to honor outstanding players and coaches who are not in the Hall of Fame. -

All Pros of 1930

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 5, No. 1 (1983) ALL PROS OF 1930 by John Hogrogian While the country endured the first year of the great Depression, Bronko Nagurski played his first season with the Chicago Bears. From day one, Nagurski dominated the field with his physical power as a runner and defender. A 1929 All-American at the University of Minnesota, he stepped into the professional ranks without a stumble and led the Bears out of the second division to a strong third place finish. Trailing the Bears in seventh place were the Chicago Cardinals, also the proud possessors of a superstar fullback. Ernie Nevers already had earned himself a reputation as the greatest back in history, both with his play at Stanford and with his pro service. The dominant force on the Cardinals, Nevers was unrivaled as the fullback extraordinaire until Nagurski came along. Only in 1930 would All Pro selectors have to weigh the merits of these two superb fullbacks. Nevers would play his final season in 1931 while Nagurski was struggling with injuries. The closeness of their talents was reflected in the annual poll of sports writers, team officials, coaches, and game officials. The ballot produced a dead heat between the two. The unnamed author of the accompanying article, writing under a Green Bay dateline, stated that the chose to make Nevers the first team fullback because of his wider range of skills. First Team E- Lavern Dilweg, GB E- Luke Johnsos, ChiB T- Jap Douds, Port T- Link Lyman, ChiB G- Mike Michalske, GB G- Walt Kiesling, ChiB C- Swede Hagberg, Bkn Q- Benny Friedman, NY H- Red Grange, ChiB H- Ken Strong, SI F- Ernie Nevers, ChiC Second Team E- Tom Nash, GB E- Red Badgro, NY T- Jim Mooney, Bkn T- Bill Kern, GB G- Hal Hanson, Fra G- Rudy Comstock, NY C- Joe Westoupal, NY Q- Red Dunn, GB H- Stumpy Thomason, Bkn H- Father Lumpkin, Port F- Bronko Nagurski, ChiB Third Team E- Chuck Kassel, ChiC E- Tony Kostos, Fra T- Duke Slater, ChiC T- Cal Hubbard, GB G- Les Caywood, NY G- Al Graham, Port 1 THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol.