Alexandra Kolesnik

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pete Doherty (Ebury)

Early in 2004 Alan Mc introduced Pete to D Hart, who had played in the Creation Recor band The Jesus and M Chain. Hart had follow The LibertinesTEN to the of England on the tra with hisALBUM Super TWO 8 cam with a view to making music video for the ba Hart would later fly o Paris to direct the Fo‘ Lovers’ video to accom the single Pete was on verge of releasing wit Wolfman in the spring Pete was still playing Early in 2004 Alan McGee introduced Pete to Douglas Hart, who had played bass in the Creation Records band The Jesus and Mary Chain. Hart had followed The Libertines to the North of England on the train with his Super 8 camera with a view to making a music video for the band. Hart would later fly out to Paris to direct the ‘For Lovers’ video to accompany the single Pete was on the verge of releasing with Wolfman in the spring. Pete was still playing solo gigs, advertising them on his website a day or two before they took place. He’d already recorded ‘For Lovers’ and was desperate to record the B-side; it was a beautiful song and he was convinced it would be a hit. He’d also finished recording the debut Babyshambles single. But Pete and Carl still wanted to write together. They needed to collaborate and bond after the debacle of their trip to the Welsh valleys, and they had a second Libertines album to write. So they decided to head to Paris. -

Dirty Pretty Things' Carl Barât Announced As Fifth Road to V Mentor

Dirty Pretty Things’ Carl Barât announced as Fifth Road to V Mentor Submitted by: onlinefire PR Wednesday, 9 April 2008 Virgin Mobile’s Road to V (http://www.roadtov.com/) in partnership with Sony Ericsson The final mentor for Virgin Mobile’s Road to V search for bands is confirmed. Song-writer, musician and DJ Carl Barât, formerly of The Libertines and current frontman of Dirty Pretty Things, is the final addition to the panel of advisers to the ‘next big thing’ in the UK’s biggest and best search for unsigned music (http://www.roadtov.com/)al talent - Road to V. The competition is now open and two bands, mentored by our very own panel of experts, will get to open the V Festival this summer, in Chelmsford and Stafford, on the 16th August. Unsigned bands (http://www.roadtov.com/) can go to www.roadtov.com and register their entry, upload their best track and tell us a bit about themselves. All the entries will then be judged by this year’s panel of music industry experts, which includes the just announced Carl Barât, Mags Revell, the promotor of V Festival, Mark Beaumont from NME, A&R man Sav Remzi and Paul Samuels from Crown Music Management. 14 bands will go through to the live stage of the competition – all of which will go on to play at either the Carling Academy in London or Liverpool, and each gig will be broadcast during the summer on Channel 4. Each judge will then give the unsigned bands (http://www.roadtov.com/) their pearls of wisdom to make it big in the music industry the viewers then decide who wins and gets the chance of a lifetime to open one of the UK’s biggest festivals. -

My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS By David R. Fisher A thesis submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Fisher on March 29, 2006. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee M ember The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE SHOEGAZER.........................................................................1 2. A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE.………..………17 3. AN ANALYSIS OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS...............................28 4. LOVELESS AND ITS LEGACY...................................................................................50 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................63 -

Babyshambles Albums Download Janie Jones (Strummerville) Purchase and Download This Album in a Wide Variety of Formats Depending on Your Needs

babyshambles albums download Janie Jones (Strummerville) Purchase and download this album in a wide variety of formats depending on your needs. Buy the album Starting at £0.99. Janie Jones (Strummerville) Copy the following link to share it. You are currently listening to samples. Listen to over 70 million songs with an unlimited streaming plan. Listen to this album and more than 70 million songs with your unlimited streaming plans. 1 month free, then £14,99/ month. Mick Jones, ComposerLyricist - JOE STRUMMER, ComposerLyricist - Tom Aitkenhead, Engineer, StudioPersonnel - Drew McConnell, Producer - The Kooks, Additional Vocals, AssociatedPerformer - We Are Scientists, Additional Vocals, AssociatedPerformer - Babyshambles, MainArtist - Mystery Jets, Additional Vocals, AssociatedPerformer - Ladyfuzz, Additional Vocals, AssociatedPerformer - Pete Doherty, Vocalist, AssociatedPerformer - Larrikin Love, Additional Vocals, AssociatedPerformer - Iain Gore, Mixer, StudioPersonnel - Statik, Producer, Engineer, StudioPersonnel - Jeremy Warmsley, Additional Vocals, AssociatedPerformer - Jamie T, Additional Vocals, AssociatedPerformer - Laura Marling, Additional Vocals, AssociatedPerformer - The Paddingtons, Additional Vocals, AssociatedPerformer - Dirty Pretty Things, Additional Vocals, AssociatedPerformer - Guillemots, Additional Vocals, AssociatedPerformer - The Maccabees, Additional Vocals, AssociatedPerformer - Andy Boyd, Producer, Executive Producer - The Rakes, Additional Vocals, AssociatedPerformer - Matt Paul, Assistant Mixer, StudioPersonnel -

Is Rock Music in Decline? a Business Perspective

Jose Dailos Cabrera Laasanen Is Rock Music in Decline? A Business Perspective Helsinki Metropolia University of Applied Sciences Bachelor of Business Administration International Business and Logistics 1405484 22nd March 2018 Abstract Author(s) Jose Dailos Cabrera Laasanen Title Is Rock Music in Decline? A Business Perspective Number of Pages 45 Date 22.03.2018 Degree Bachelor of Business Administration Degree Programme International Business and Logistics Instructor(s) Michael Keaney, Senior Lecturer Rock music has great importance in the recent history of human kind, and it is interesting to understand the reasons of its de- cline, if it actually exists. Its legacy will never disappear, and it will always be a great influence for new artists but is important to find out the reasons why it has become what it is in now, and what is the expected future for the genre. This project is going to be focused on the analysis of some im- portant business aspects related with rock music and its de- cline, if exists. The collapse of Gibson guitars will be analyzed, because if rock music is in decline, then the collapse of Gibson is a good evidence of this. Also, the performance of independ- ent and major record labels through history will be analyzed to understand better the health state of the genre. The same with music festivals that today seem to be increasing their popularity at the expense of smaller types of live-music events. Keywords Rock, music, legacy, influence, artists, reasons, expected, fu- ture, genre, analysis, business, collapse, -

|||GET||| Young Marble Giants Colossal Youth 1St Edition

YOUNG MARBLE GIANTS COLOSSAL YOUTH 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Michael Blair | 9781501321146 | | | | | Young Marble Giants announce 40th anniversary reissue of "Colossal Youth" Monday 21 September The artwork of the album was inspired by the Beatles album With the Beatles. Both are excellent and were considered groundbreaking in the 's. The Guardian. The YMGs used tape recordings of Joyce's home-made drum machine since they did not wish to have a drummer. This article needs additional citations for verification. Hen Ogledd share new track, "Space Golf" 22nd September Thursday 13 August Monday 31 August February 29, Outstanding and as unique as it gets. A special edition reissue of one of the most influential post-punk albums of all time. Download as PDF Printable version. Saturday 18 July Monday 5 October At the Factory Festival, NivellesBelgium, Wurlitzer Jukebox! It doesn't really sound like anything else. Monday 25 May Buy Loading. Wednesday 7 October They performed one new song, "Alright," on this special. Searching For Mr Right. And still great today. They were also interested Young Marble Giants Colossal Youth 1st edition effects devices such as ring modulators and reverb units, with the emphasis always on simplicity. Archived from the original on 18 June Sunday 12 July Thursday 3 September Thursday 14 May Tuesday 29 September Young Marble Giants' last show was Young Marble Giants Colossal Youth 1st edition London in August Hay-on-Wye was not a one-off. Friday 8 May Related Tags post-punk new wave 80s post punk s Add tags View all tags. Now based in the West Country, Moxham is still writing songs. -

Be a Junkie. Be a Thief. but Must You Date Kate Moss?

February 20, 2005 Be a Junkie. Be a Thief. But Must You Date Kate Moss? Yui Mok/European Pressphoto Agency Chaos before the storm: the singer and guitarist Pete Doherty performing with his band Babyshambles in London in January. By DOMINIC PATTEN VEN by the standards of the great rock-'n'-roll train wrecks, these have been rough times for Pete Doherty. Sure, the 25-year-old frontman of the band Babyshambles has had tremendous musical success. And sure, he has enjoyed the company - in parties and gossip columns - of the glamorous Kate Moss. But that was before he was arrested on Feb. 2 on charges of robbery and blackmail. After that he spent five very unglamorous days in the Pentonville Prison in London, suffering from a painful heroin withdrawal and wondering whether anyone could raise £150,000 (about $280,230) for his bail. No one could claim to be entirely surprised by his fall. After gaining some attention in his teens as a poet, Mr. Doherty formed the Libertines with Carl Barat. With their street-urchin image and dark thrashy tunes of urban squalor, the band was described as "Britpop meets Baudelaire," and the two songwriters were compared to Morrissey and Johnny Marr of the Smiths. Their first album, "Up the Bracket," debuted in the British Top 20 in late 2002, and soon went platinum. But in addition to his musical talent, Mr. Doherty demonstrated an effortless knack for getting himself in trouble. In June 2003 he entered the first of many stints in rehab, only to walk away days later. -

A&R Update December 1-2-3-4 GO! RECORDS 423

A&R Update December 1-2-3-4 GO! RECORDS 423 40th St. Ste. 5 Oakland, CA 94609 510-985-0325 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.1234gorecords.com 4AD RECORDS 17-19 Alma Rd. London, SW 18, 1AA, UK E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.4ad.com Roster: Blonde Redhead, Anni Rossi, St. Vincent, Camera Obscura Additional locations: 304 Hudson St., 7th Fl. New York, NY 10013 2035 Hyperion Ave. Los Angeles, CA 90027 825 RECORDS, INC. Brooklyn, N.Y. 917-520-6855 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.825Records.com Styles/Specialties: Artist development, solo artists, singer-songwriters, pop, rock, R&B 10TH PLANET RECORDS P.O. Box 10114 Fairbanks, AK 99710 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.10thplanet.com 21ST CENTURY RECORDS Silver Lake, CA 323-661-3130 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.21stcenturystudio.com Contact: Burt Levine 18TH & VINE RECORDS ALLEGRO MEDIA GROUP 20048 N.E. San Rafael St. Portland, OR 97230 503-491-8480, 800-288-2007 Website: www.allegro-music.com Genres: jazz, bebop, soul-jazz 21ST CENTURY STUDIO Silver Lake, CA 323-661-3130 Email Address: [email protected] Website: www.21stcenturystudio.com Genres: rock, folk, ethnic, acoustic groups, books on tape, actor voice presentations Burt Levine, A&R 00:02:59 LLC PO Box 1251 Culver City, CA 90232 718-636-0259 Website: www.259records.com Email Address: [email protected] 4AD RECORDS 2035 Hyperion Ave. Los Angeles, CA 90027 Email Address: [email protected] Website: www.4ad.com Clients: The National, Blonde Redhead, Deerhunter, Efterklang, St. -

Disques D'or 2009

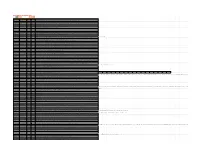

SINGLES OR 2009 (150 000 exemplaires vendus) DATE DE DATE DE TITRES EDITEUR PRODUCTEUR ARTISTES SORTIE CONSTAT MERCURY J'AIMERAIS TELLEMENT 05/10/2009 22/12/2009 JENA UNIVERSAL MUSIC France SQUARE RIVOLI PUBLISHING EMI WHEN LOVE TAKES OVER 12/06/2009 21/12/2009 DAVID GUETTA MUSIC France SQUARE RIVOLI PUBLISHING EMI SEXY BITCH 28/08/2009 21/12/2009 DAVID GUETTA MUSIC France SQUARE RIVOLI PUBLISHING EMI BABY WHEN THE LIGHT 12/10/2007 21/12/2009 DAVID GUETTA MUSIC France EMI RECORDS LTD FUCK YOU 10/07/2009 21/12/2009 LILLY ALLEN EMI MUSIC France CAPITOL RECORDS EMI I KISSED A GIRL 22/08/2009 21/12/2009 KATY PERRY MUSIC France SINGLES PLATINE 2009 (250 000 exemplaires vendus) DATE DE DATE DE TITRES EDITEUR PRODUCTEUR ARTISTES SORTIE CONSTAT SPECIAL MARKETING SONY CA M'ENERVE 16/03/2009 22/10/2009 HELMUT FRITZ BMG ALBUMS OR (50 000 ex.) POLYDOR ABBA THE DEFINITIVE COLLECTION 31/08/2009 21/12/2009 UNIVERSAL MUSIC France POLYDOR ABD AL MALIK DANTE 03/11/2008 05/02/2009 UNIVERSAL MUSIC France JIVE EPIC THE ELEMENT OF FREEDOM 11/12/2009 15/12/2009 ALICIA KEYS SONY BMG WARNER AMAURY VASSILI VINCERO 23/03/2009 24/06/2009 WARNER MUSIC France JIVE EPIC OU JE VAIS 04/12/2009 15/12/2009 AMEL BENT SONY BMG POLYDOR ANAIS THE LOVE ALBUM 10/11/2008 05/02/2009 UNIVERSAL MUSIC France POLYDOR ANDRE RIEU PASSIONNEMENT 24/11/2008 05/02/2009 UNIVERSAL MUSIC France POLYDOR ANDRE RIEU A TOI 16/11/2009 21/12/2009 UNIVERSAL MUSIC France ASSASSIN PRODUCTION EMI ASSASSIN TOUCHE D'ESPOIR 27/03/2000 30/07/2009 MUSIC France WARNER NICO TEEN LOVE 16/11/2009 10/12/2009 B B BRUNES WARNER MUSIC France WEA B.O.F. -

RSD List 2020

Artist Title Label Format Format details/ Reason behind release 3 Pieces, The Iwishcan William Rogue Cat Resounds12" Full printed sleeve - black 12" vinyl remastered reissue of this rare cosmic, funked out go-go boogie bomb, full of rapping gold from Washington D.C's The 3 Pieces.Includes remixes from Dan Idjut / The Idjut Boys & LEXX Aashid Himons The Gods And I Music For Dreams /12" Fyraften Musik Aashid Himons classic 1984 Electonic/Reggae/Boogie-Funk track finally gets a well deserved re-issue.Taken from the very rare sought after album 'Kosmik Gypsy.The EP includes the original mix, a lovingly remastered Fyraften 2019 version.Also includes 'In a Figga of Speech' track from Kosmik Gypsy. Ace Of Base The Sign !K7 Records 7" picture disc """The Sign"" is a song by the Swedish band Ace of Base, which was released on 29 October 1993 in Europe. It was an international hit, reaching number two in the United Kingdom and spending six non-consecutive weeks at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in the United States. More prominently, it became the top song on Billboard's 1994 Year End Chart. It appeared on the band's album Happy Nation (titled The Sign in North America). This exclusive Record Store Day version is pressed on 7"" picture disc." Acid Mothers Temple Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo (Title t.b.c.)Space Age RecordingsDouble LP Pink coloured heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP Not previously released on vinyl Al Green Green Is Blues Fat Possum 12" Al Green's first record for Hi Records, celebrating it's 50th anniversary.Tip-on Jacket, 180 gram vinyl, insert with liner notes.Split green & blue vinyl Acid Mothers Temple & the Melting Paraiso U.F.O.are a Japanese psychedelic rock band, the core of which formed in 1995.The band is led by guitarist Kawabata Makoto and early in their career featured many musicians, but by 2004 the line-up had coalesced with only a few core members and frequent guest vocalists. -

The Libertines in Arrivo Con Un Nuovo Disco E Tour

The Libertines in arrivo con un nuovo disco e tour I The Libertines, band culto degli anni 2000, formata dal celeberrimo Pete Doherty ed il poliedrico Carl Barat, dopo aver finalmente annunciato il loro ritorno sulle scene, consacrato da un gremitissimo concerto ad Hyde Park con più di 65.000 presenze lo scorso luglio, sono pronti ad arrivare anche in Italia per una unica, imperdibile, data evento. Nel corso degli ultimi 15 anni si è costantemente sentito parlare della band di east London, sia per la perfezione musicale e stilistica dei suoi due album, Up The Bracket e The Libertines, sia per il life style totalmente punk dei suoi componenti. Icone di stile, poeti maledetti, protagonisti dei tabloid, i The Libertines sono riusciti a rimanere, nel bene o nel male, sulla bocca di tutti. L’estate scorsa, dopo il leggendario live ad Hyde Park, è finalmente arrivata la notizia che il gruppo si sarebbe riunito per registrare il terzo, attesissimo, album da presentare poi in giro per il mondo con un tour nelle più grandi arene. Alex Turner degli Arctic Monkeys ha dichiarato: «Questa è una delle più belle notizie, siamo cresciuti conUp The Bracket nelle orecchie. Vederli di nuovo sul palco sarebbe stupendo». Lo stesso Pete Doherty ha affermato in una recente intervista al The Independent: «I Boys In The Band (titolo di uno dei loro pezzi più famosi, ndr) sono di nuovo insieme e siamo pronti a portare sul palco tutta la nostra energia!». NME Magazine ha messo il loro terzo disco, non ancora scritto, tra i “50 album da ascoltare assolutamente durante il 2015”. -

Jul - Aug 2016 “That Scrappy Magazine from Citr101.9FM” “House of Glass," and “Acidic.” This Lends Some Confident Sentence

Jul - Aug 2016 “that scrappy magazine from CiTR101.9FM” “House of Glass," and “Acidic.” This lends some confident sentence. Sean Mallion and the rest repetition, but is not a major detriment. of the ADSR team are devoted to supporting “Shivering” is the best track on the album. non-mainstream electro-music artists, mani- There is also an addition of a choir halfway festing in multiple events, extensive blogging, through the song that, while unexpected from and the recent launch of the ADSR music label. Holy Fuck, fits in the context. The track then It is already sunrise in the land of the Korean transitions into a calm instrumental break before producer Honbul. In “Asura Break,” spirits sing building up to a climax with distorted guitars join- away the night. Their loose ribbons dance in ing the rest of the instruments in conclusion. the air producing modern trip-hop waves which The album’s only issue is that it is not cohe- crush upon ancient percussions of Buddhist sive. Of course there are many tracks here that monks. In “Shake,” elements of glitch, chill explore the same sounds and instruments, but beats and downtempo, temperamental drums they do not add anything to the album on top and earthly voices chase each other in a joyful of one another. For instance, “Tom Tom” is game of life — Honbul is a good example of merely an instrumental electro pop track with how to master electronica’s chi. a steady beat, a repetitive distorted vocal mel- This set atmosphere follows Tokiomi Tsuta ody and bassline that never evolves into some- with “Coelacanth and “Night time in Tofino,” thing more.