Arxiv:1811.08034V1 [Hep-Ph] 20 Nov 2018 & Tion Seems to Suggest a Sizeable Hierarchy in the Sfermion Model the Strong Dynamics with a Slice of Ads5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pev-Scale Split Supersymmetry from Higgs Mass and Electroweak Vacuum Stability

The PeV-Scale Split Supersymmetry from Higgs Mass and Electroweak Vacuum Stability Waqas Ahmed ? 1, Adeel Mansha ? 2, Tianjun Li ? ~ 3, Shabbar Raza ∗ 4, Joydeep Roy ? 5, Fang-Zhou Xu ? 6, ? CAS Key Laboratory of Theoretical Physics, Institute of Theoretical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190, P. R. China ~School of Physical Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, No. 19A Yuquan Road, Beijing 100049, P. R. China ∗ Department of Physics, Federal Urdu University of Arts, Science and Technology, Karachi 75300, Pakistan Institute of Modern Physics, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China Abstract The null results of the LHC searches have put strong bounds on new physics scenario such as supersymmetry (SUSY). With the latest values of top quark mass and strong coupling, we study the upper bounds on the sfermion masses in Split-SUSY from the observed Higgs boson mass and electroweak (EW) vacuum stability. To be consistent with the observed Higgs mass, we find that the largest value of supersymmetry breaking 3 1:5 scales MS for tan β = 2 and tan β = 4 are O(10 TeV) and O(10 TeV) respectively, thus putting an upper bound on the sfermion masses around 103 TeV. In addition, the Higgs quartic coupling becomes negative at much lower scale than the Standard Model (SM), and we extract the upper bound of O(104 TeV) on the sfermion masses from EW vacuum stability. Therefore, we obtain the PeV-Scale Split-SUSY. The key point is the extra contributions to the Renormalization Group Equation (RGE) running from arXiv:1901.05278v1 [hep-ph] 16 Jan 2019 the couplings among Higgs boson, Higgsinos, and gauginos. -

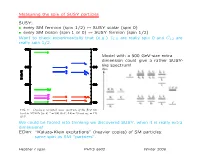

Measuring the Spin of SUSY Particles SUSY: • Every SM Fermion (Spin 1/2

Measuring the spin of SUSY particles SUSY: • every SM fermion (spin 1/2) ↔ SUSY scalar (spin 0) • every SM boson (spin 1 or 0) ↔ SUSY fermion (spin 1/2) Want to check experimentally that (e.g.) eL,R are really spin 0 and Ce1,2 are really spin 1/2. 2 preserve the 5th dimensional momentum (KK number). The corresponding coupling constants among KK modes Model with a 500 GeV-size extra are simply equal to the SM couplings (up to normaliza- tion factors such as √2). The Feynman rules for the KK dimension could give a rather SUSY- modes can easily be derived (e.g., see Ref. [8, 9]). like spectrum! In contrast, the coefficients of the boundary terms are not fixed by Standard Model couplings and correspond to new free parameters. In fact, they are renormalized by the bulk interactions and hence are scale dependent [10, 11]. One might worry that this implies that all pre- dictive power is lost. However, since the wave functions of Standard Model fields and KK modes are spread out over the extra dimension and the new couplings only exist on the boundaries, their effects are volume sup- pressed. We can get an estimate for the size of these volume suppressed corrections with naive dimensional analysis by assuming strong coupling at the cut-off. The FIG. 1: One-loop corrected mass spectrum of the first KK −1 result is that the mass shifts to KK modes from bound- level in MUEDs for R = 500 GeV, ΛR = 20 and mh = 120 ary terms are numerically equal to corrections from loops GeV. -

Electroweak Radiative B-Decays As a Test of the Standard Model and Beyond Andrey Tayduganov

Electroweak radiative B-decays as a test of the Standard Model and beyond Andrey Tayduganov To cite this version: Andrey Tayduganov. Electroweak radiative B-decays as a test of the Standard Model and beyond. Other [cond-mat.other]. Université Paris Sud - Paris XI, 2011. English. NNT : 2011PA112195. tel-00648217 HAL Id: tel-00648217 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00648217 Submitted on 5 Dec 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. LAL 11-181 LPT 11-69 THESE` DE DOCTORAT Pr´esent´eepour obtenir le grade de Docteur `esSciences de l’Universit´eParis-Sud 11 Sp´ecialit´e:PHYSIQUE THEORIQUE´ par Andrey Tayduganov D´esint´egrationsradiatives faibles de m´esons B comme un test du Mod`eleStandard et au-del`a Electroweak radiative B-decays as a test of the Standard Model and beyond Soutenue le 5 octobre 2011 devant le jury compos´ede: Dr. J. Charles Examinateur Prof. A. Deandrea Rapporteur Prof. U. Ellwanger Pr´esident du jury Prof. S. Fajfer Examinateur Prof. T. Gershon Rapporteur Dr. E. Kou Directeur de th`ese Dr. A. Le Yaouanc Directeur de th`ese Dr. -

The Minimal Supersymmetric Standard Model: Group Summary Report

PM/98–45 December 1998 The Minimal Supersymmetric Standard Model: Group Summary Report Conveners: A. Djouadi1, S. Rosier-Lees2 Working Group: M. Bezouh1, M.-A. Bizouard3,C.Boehm1, F. Borzumati1;4,C.Briot2, J. Carr5,M.B.Causse6, F. Charles7,X.Chereau2,P.Colas8, L. Duflot3, A. Dupperin9, A. Ealet5, H. El-Mamouni9, N. Ghodbane9, F. Gieres9, B. Gonzalez-Pineiro10, S. Gourmelen9, G. Grenier9, Ph. Gris8, J.-F. Grivaz3,C.Hebrard6,B.Ille9, J.-L. Kneur1, N. Kostantinidis5, J. Layssac1,P.Lebrun9,R.Ledu11, M.-C. Lemaire8, Ch. LeMouel1, L. Lugnier9 Y. Mambrini1, J.P. Martin9,G.Montarou6,G.Moultaka1, S. Muanza9,E.Nuss1, E. Perez8,F.M.Renard1, D. Reynaud1,L.Serin3, C. Thevenet9, A. Trabelsi8,F.Zach9,and D. Zerwas3. 1 LPMT, Universit´e Montpellier II, F{34095 Montpellier Cedex 5. 2 LAPP, BP 110, F{74941 Annecy le Vieux Cedex. 3 LAL, Universit´e de Paris{Sud, Bat{200, F{91405 Orsay Cedex 4 CERN, Theory Division, CH{1211, Geneva, Switzerland. 5 CPPM, Universit´e de Marseille-Luminy, Case 907, F-13288 Marseille Cedex 9. 6 LPC Clermont, Universit´e Blaise Pascal, F{63177 Aubiere Cedex. 7 GRPHE, Universit´e de Haute Alsace, Mulhouse 8 SPP, CEA{Saclay, F{91191 Cedex 9 IPNL, Universit´e Claude Bernard de Lyon, F{69622 Villeurbanne Cedex. 10 LPNHE, Universit´es Paris VI et VII, Paris Cedex. 11 CPT, Universit´e de Marseille-Luminy, Case 907, F-13288 Marseille Cedex 9. Report of the MSSM working group for the Workshop \GDR{Supersym´etrie". 1 CONTENTS 1. Synopsis 4 2. The MSSM Spectrum 9 2.1 The MSSM: Definitions and Properties 2.1.1 The uMSSM: unconstrained MSSM 2.1.2 The pMSSM: “phenomenological” MSSM 2.1.3 mSUGRA: the constrained MSSM 2.1.4 The MSSMi: the intermediate MSSMs 2.2 Electroweak Symmetry Breaking 2.2.1 General features 2.2.2 EWSB and model–independent tanβ bounds 2.3 Renormalization Group Evolution 2.3.1 The one–loop RGEs 2.3.2 Exact solutions for the Yukawa coupling RGEs 3. -

The Magnetic Dipole Moment of the Muon in Different SUSY Models

The magnetic dipole moment of the muon in different SUSY models Bachelor-Arbeit zur Erlangung des Hochschulgrades Bachelor of Science im Bachelor-Studiengang Physik vorgelegt von Jobst Ziebell geboren am 05.11.1992 in Herrljunga Institut für Kern- und Teilchenphysik Fachrichtung Physik Fakultät Mathematik und Naturwissenschaften Technische Universität Dresden 2015 Eingereicht am 1. Juli 2015 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Dominik Stöckinger 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Kai Zuber Abstract The magnetic dipole moment of the muon is one of the most precisely measured quantities in modern physics. Theory however predicts values that disagree with measurement by several standard deviations [1, Abstract]. Because this may hint at physics beyond the standard model, it is a great opportunity to ex- amine the magnetic dipole moment in different supersymmetric models. It is then possible to calculate dependences of the dipole moment on various model parameters as well as to find constraints for their particular values. The purpose of this paper is to describe how the magnetic dipole moment is obtained in su- persymmetric extensions of the standard model and to document the implementation of its calculation in FlexibleSUSY, a spectrum generator for supersymmetric models [2, Abstract]. Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 The gyromagnetic ratio 2 2.1 In classical mechanics . .2 2.2 In quantum mechanics . .3 2.3 In quantum field theory . .4 3 The implementation in FlexibleSUSY 7 3.1 The C++ part . .7 3.2 The Mathematica part . 11 3.3 The FlexibleSUSY part . 12 4 Results 13 Appendices 17 A The Loop functions . 17 B The VertexFunction template . 17 C The DiagramEvaluator<...>::value() functions . -

Supersymmetric Particle Searches

Citation: K.A. Olive et al. (Particle Data Group), Chin. Phys. C38, 090001 (2014) (URL: http://pdg.lbl.gov) Supersymmetric Particle Searches A REVIEW GOES HERE – Check our WWW List of Reviews A REVIEW GOES HERE – Check our WWW List of Reviews SUPERSYMMETRIC MODEL ASSUMPTIONS The exclusion of particle masses within a mass range (m1, m2) will be denoted with the notation “none m m ” in the VALUE column of the 1− 2 following Listings. The latest unpublished results are described in the “Supersymmetry: Experiment” review. A REVIEW GOES HERE – Check our WWW List of Reviews CONTENTS: χ0 (Lightest Neutralino) Mass Limit 1 e Accelerator limits for stable χ0 − 1 Bounds on χ0 from dark mattere searches − 1 χ0-p elastice cross section − 1 eSpin-dependent interactions Spin-independent interactions Other bounds on χ0 from astrophysics and cosmology − 1 Unstable χ0 (Lighteste Neutralino) Mass Limit − 1 χ0, χ0, χ0 (Neutralinos)e Mass Limits 2 3 4 χe ,eχ e(Charginos) Mass Limits 1± 2± Long-livede e χ± (Chargino) Mass Limits ν (Sneutrino)e Mass Limit Chargede Sleptons e (Selectron) Mass Limit − µ (Smuon) Mass Limit − e τ (Stau) Mass Limit − e Degenerate Charged Sleptons − e ℓ (Slepton) Mass Limit − q (Squark)e Mass Limit Long-livede q (Squark) Mass Limit b (Sbottom)e Mass Limit te (Stop) Mass Limit eHeavy g (Gluino) Mass Limit Long-lived/lighte g (Gluino) Mass Limit Light G (Gravitino)e Mass Limits from Collider Experiments Supersymmetrye Miscellaneous Results HTTP://PDG.LBL.GOV Page1 Created: 8/21/2014 12:57 Citation: K.A. Olive et al. -

R-Parity Violation and Light Neutralinos at Ship and the LHC

BONN-TH-2015-12 R-Parity Violation and Light Neutralinos at SHiP and the LHC Jordy de Vries,1, ∗ Herbi K. Dreiner,2, y and Daniel Schmeier2, z 1Institute for Advanced Simulation, Institut f¨urKernphysik, J¨ulichCenter for Hadron Physics, Forschungszentrum J¨ulich, D-52425 J¨ulich, Germany 2Physikalisches Institut der Universit¨atBonn, Bethe Center for Theoretical Physics, Nußallee 12, 53115 Bonn, Germany We study the sensitivity of the proposed SHiP experiment to the LQD operator in R-Parity vi- olating supersymmetric theories. We focus on single neutralino production via rare meson decays and the observation of downstream neutralino decays into charged mesons inside the SHiP decay chamber. We provide a generic list of effective operators and decay width formulae for any λ0 cou- pling and show the resulting expected SHiP sensitivity for a widespread list of benchmark scenarios via numerical simulations. We compare this sensitivity to expected limits from testing the same decay topology at the LHC with ATLAS. I. INTRODUCTION method to search for a light neutralino, is via the pro- duction of mesons. The rate for the latter is so high, Supersymmetry [1{3] is the unique extension of the ex- that the subsequent rare decay of the meson to the light ternal symmetries of the Standard Model of elementary neutralino via (an) R-parity violating operator(s) can be particle physics (SM) with fermionic generators [4]. Su- searched for [26{28]. This is analogous to the production persymmetry is necessarily broken, in order to comply of neutrinos via π or K-mesons. with the bounds from experimental searches. -

![Explaining Muon G − 2 Data in the Μνssm Arxiv:1912.04163V3 [Hep-Ph]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8110/explaining-muon-g-2-data-in-the-ssm-arxiv-1912-04163v3-hep-ph-1328110.webp)

Explaining Muon G − 2 Data in the Μνssm Arxiv:1912.04163V3 [Hep-Ph]

Explaining muon g 2 data in the µνSSM − Essodjolo Kpatcha∗a,b, Iñaki Lara†c, Daniel E. López-Fogliani‡d,e, Carlos Muñoz§a,b, and Natsumi Nagata¶f aDepartamento de Física Teórica, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (UAM), Campus de Cantoblanco, 28049 Madrid, Spain bInstituto de Física Teórica (IFT) UAM-CSIC, Campus de Cantoblanco, 28049 Madrid, Spain cFaculty of Physics, University of Warsaw, Pasteura 5, 02-093 Warsaw, Poland dInstituto de Física de Buenos Aires UBA & CONICET, Departamento de Física, Facultad de Ciencia Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 1428 Buenos Aires, Argentina e Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina, 1107 Buenos Aires, Argentina fDepartment of Physics, University of Tokyo, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan Abstract We analyze the anomalous magnetic moment of the muon g 2 in the µνSSM. − This R-parity violating model solves the µ problem reproducing simultaneously neu- trino data, only with the addition of right-handed neutrinos. In the framework of the µνSSM, light left muon-sneutrino and wino masses can be naturally obtained driven by neutrino physics. This produces an increase of the dominant chargino-sneutrino loop contribution to muon g 2, solving the gap between the theoretical computation − and the experimental data. To analyze the parameter space, we sample the µνSSM using a likelihood data-driven method, paying special attention to reproduce the cur- rent experimental data on neutrino and Higgs physics, as well as flavor observables such as B and µ decays. We then apply the constraints from LHC searches for events with multi-leptons + MET on the viable regions found. They can probe these regions through chargino-chargino, chargino-neutralino and neutralino-neutralino pair pro- duction. -

Precise MSSM Prediction for (G-2) of the Muon

CoEPP–MN–15–10 DESY 15-193 FTUV–15–6502 IFIC–15–76 GM2Calc: Precise MSSM prediction for (g − 2) of the muon Peter Athrona, Markus Bachb, Helvecio G. Fargnolic, Christoph Gnendigerb, Robert Greifenhagenb, Jae-hyeon Parkd, Sebastian Paßehre, Dominik Stockinger¨ b, Hyejung Stockinger-Kim¨ b, Alexander Voigte aARC Centre of Excellence for Particle Physics at the Terascale, School of Physics, Monash University, Victoria 3800 bInstitut f¨ur Kern- und Teilchenphysik, TU Dresden, Zellescher Weg 19, 01069 Dresden, Germany cDepartamento de Ciˆencias Exatas, Universidade Federal de Lavras, 37200-000, Lavras, Brazil dDepartament de F´ısica Te`orica and IFIC, Universitat de Val`encia-CSIC, 46100, Burjassot, Spain eDeutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron DESY, Notkestraße 85, 22607 Hamburg, Germany Abstract We present GM2Calc, a public C++ program for the calculation of MSSM contributions to the anomalous magnetic moment of the muon, (g 2) . The code computes (g 2) precisely, by taking into account − µ − µ the latest two-loop corrections and by performing the calculation in a physical on-shell renormalization scheme. In particular the program includes a tan β resummation so that it is valid for arbitrarily high values of tan β, as well as fermion/sfermion-loop corrections which lead to non-decoupling effects from heavy squarks. GM2Calc can be run with a standard SLHA input file, internally converting the input into on- shell parameters. Alternatively, input parameters may be specified directly in this on-shell scheme. In both cases the input file allows one to switch on/off individual contributions to study their relative impact. This paper also provides typical usage examples not only in conjunction with spectrum generators and plotting programs but also as C++ subroutines linked to other programs. -

Experimental Constraint on Quark Electric Dipole Moments

Experimental constraint on quark electric dipole moments Tianbo Liu,1, 2, ∗ Zhiwen Zhao,1 and Haiyan Gao1, 2 1Department of Physics, Duke University and Triangle Universities Nuclear Laboratory, Durham, North Carolina 27708, USA 2Duke Kunshan University, Kunshan, Jiangsu 215316, China The electric dipole moments (EDMs) of nucleons are sensitive probes of additional CP violation sources beyond the standard model to account for the baryon number asymmetry of the universe. As a fundamental quantity of the nucleon structure, tensor charge is also a bridge that relates nucleon EDMs to quark EDMs. With a combination of nucleon EDM measurements and tensor charge extractions, we investigate the experimental constraint on quark EDMs, and its sensitivity to CP violation sources from new physics beyond the electroweak scale. We obtain the current limits on quark EDMs as 1:27×10−24 e·cm for the up quark and 1:17×10−24 e·cm for the down quark at the scale of 4 GeV2. We also study the impact of future nucleon EDM and tensor charge measurements, and show that upcoming new experiments will improve the constraint on quark EDMs by about three orders of magnitude leading to a much more sensitive probe of new physics models. I. INTRODUCTION one can derive it from nucleon EDM measurements. A bridge that relates the quark EDM and the nucleon EDM Symmetries play a central role in physics. Discrete is the tensor charge, which is a fundamental QCD quan- symmetries, charge conjugate (C), parity (P), and time- tity defined by the matrix element of the tensor cur- reversal (T ), were believed to be conserved until the dis- rent. -

Bino Variations: Effective Field Theory Methods for Dark Matter Direct Detection

PHYSICAL REVIEW D 93, 095008 (2016) Bino variations: Effective field theory methods for dark matter direct detection Asher Berlin,1 Denis S. Robertson,2,3,4 Mikhail P. Solon,2,3 and Kathryn M. Zurek2,3 1Department of Physics, Enrico Fermi Institute, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 60637, USA 2Theoretical Physics Group, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, California 94709, USA 3Berkeley Center for Theoretical Physics, University of California, Berkeley, California 94709, USA 4Instituto de Física, Universidade de São, Paulo R. do Matão, 187, São Paulo, São 05508-900, Brazil (Received 7 December 2015; published 10 May 2016) We apply effective field theory methods to compute bino-nucleon scattering, in the case where tree-level interactions are suppressed and the leading contribution is at loop order via heavy flavor squarks or sleptons. We find that leading log corrections to fixed-order calculations can increase the bino mass reach of direct detection experiments by a factor of 2 in some models. These effects are particularly large for the bino-sbottom coannihilation region, where bino dark matter as heavy as 5–10 TeV may be detected by near future experiments. For the case of stop- and selectron-loop mediated scattering, an experiment reaching the neutrino background will probe thermal binos as heavy as 500 and 300 GeV, respectively. We present three key examples that illustrate in detail the framework for determining weak scale coefficients, and for mapping onto a low-energy theory at hadronic scales, through a sequence of effective theories and renormalization group evolution. For the case of a squark degenerate with the bino, we extend the framework to include a squark degree of freedom at low energies using heavy particle effective theory, thus accounting for large logarithms through a “heavy-light current.” Benchmark predictions for scattering cross sections are evaluated, including complete leading order matching onto quark and gluon operators, and a systematic treatment of perturbative and hadronic uncertainties. -

Supersymmetry: Lecture 2: the Supersymmetrized Standard Model

Supersymmetry: Lecture 2: The Supersymmetrized Standard Model Yael Shadmi Technion June 2014 Yael Shadmi (Technion) ESHEP June 2014 1 / 91 Part I: The Supersymmetrized SM: motivation and structure before 2012, all fundamental particles we knew had spin 1 or spin 1/2 but we now have the Higgs: it's spin 0 of course spin-0 is the simplest possibility spin-1 is intuitive too (we all understand vectors) the world and (QM courses) would have been very different if the particle we know best, the electron, were spin-0 supersymmetry: boson $ fermion so from a purely theoretical standpoint, supersymmetry would provide an explanation for why we have particles of different spins Yael Shadmi (Technion) ESHEP June 2014 2 / 91 The Higgs and fine tuning: because the Higgs is spin-0, its mass is quadratically divergent 2 2 δm / ΛUV (1) unlike fermions (protected by chiral symmetry) gauge bosons (protected by gauge symmetry) Yael Shadmi (Technion) ESHEP June 2014 3 / 91 Higgs Yukawa coupling: quark (top) contribution also, gauge boson, Higgs loops Yael Shadmi (Technion) ESHEP June 2014 4 / 91 practically: we don't care (can calculate anything in QFT, just put in a counter term) theoretically: believe ΛUV is a concrete physical scale, eg: mass of new fields, scale of new strong interactions then 2 2 2 m (µ) = m (ΛUV ) + # ΛUV (2) 2 m (ΛUV ) determined by the full UV theory # determined by SM we know LHS: m2 ∼ 1002 GeV2 18 if ΛUV = 10 GeV 2 36 2 we need m (ΛUV ) ∼ 10 GeV and the 2 terms on RHS tuned to 32 orders of magnitude.