A Geological Analysis of the Appalachian Basin And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stratigraphic Succession in Lower Peninsula of Michigan

STRATIGRAPHIC DOMINANT LITHOLOGY ERA PERIOD EPOCHNORTHSTAGES AMERICANBasin Margin Basin Center MEMBER FORMATIONGROUP SUCCESSION IN LOWER Quaternary Pleistocene Glacial Drift PENINSULA Cenozoic Pleistocene OF MICHIGAN Mesozoic Jurassic ?Kimmeridgian? Ionia Sandstone Late Michigan Dept. of Environmental Quality Conemaugh Grand River Formation Geological Survey Division Late Harold Fitch, State Geologist Pennsylvanian and Saginaw Formation ?Pottsville? Michigan Basin Geological Society Early GEOL IN OG S IC A A B L N Parma Sandstone S A O G C I I H E C T I Y Bayport Limestone M Meramecian Grand Rapids Group 1936 Late Michigan Formation Stratigraphic Nomenclature Project Committee: Mississippian Dr. Paul A. Catacosinos, Co-chairman Mark S. Wollensak, Co-chairman Osagian Marshall Sandstone Principal Authors: Dr. Paul A. Catacosinos Early Kinderhookian Coldwater Shale Dr. William Harrison III Robert Reynolds Sunbury Shale Dr. Dave B.Westjohn Mark S. Wollensak Berea Sandstone Chautauquan Bedford Shale 2000 Late Antrim Shale Senecan Traverse Formation Traverse Limestone Traverse Group Erian Devonian Bell Shale Dundee Limestone Middle Lucas Formation Detroit River Group Amherstburg Form. Ulsterian Sylvania Sandstone Bois Blanc Formation Garden Island Formation Early Bass Islands Dolomite Sand Salina G Unit Paleozoic Glacial Clay or Silt Late Cayugan Salina F Unit Till/Gravel Salina E Unit Salina D Unit Limestone Salina C Shale Salina Group Salina B Unit Sandy Limestone Salina A-2 Carbonate Silurian Salina A-2 Evaporite Shaley Limestone Ruff Formation -

Outcrop Lithostratigraphy and Petrophysics of the Middle Devonian Marcellus Shale in West Virginia and Adjacent States

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2011 Outcrop Lithostratigraphy and Petrophysics of the Middle Devonian Marcellus Shale in West Virginia and Adjacent States Margaret E. Walker-Milani West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Walker-Milani, Margaret E., "Outcrop Lithostratigraphy and Petrophysics of the Middle Devonian Marcellus Shale in West Virginia and Adjacent States" (2011). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 3327. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/3327 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Outcrop Lithostratigraphy and Petrophysics of the Middle Devonian Marcellus Shale in West Virginia and Adjacent States Margaret E. Walker-Milani THESIS submitted to the College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Geology Richard Smosna, Ph.D., Chair Timothy Carr, Ph.D. John Renton, Ph.D. Kathy Bruner, Ph.D. -

Late Devonian and Early Mississippian Distal Basin-Margin Sedimentation of Northern Ohio1

Late Devonian and Early Mississippian Distal Basin-Margin Sedimentation of Northern Ohio1 THOMAS L. LEWIS, Department of Geological Sciences, Cleveland State University, Cleveland, OH 44115 ABSTRACT. Clastic sediments, derived from southeastern, eastern and northeastern sources, prograded west- ward into a shallow basin at the northwestern margin of the Appalachian Basin in Late Devonian and Early Mississippian time. The western and northwestern boundary of the basin was the submerged Cincinnati Arch. The marine clastic wedges provided a northwest paleoslope and a distal, gentle shelf-edge margin that controlled directional emplacement of coarse elastics. Rising sea levels coupled with differences in sedimen- tation rates and localized soft-sediment deformation within the basin help explain some features of the Bedford and Berea Formations. The presence of sand-filled mudcracks and flat-topped symmetrical ripple marks in the Berea Formation attest to very shallow water deposition and local subaerial exposure at the time of emplacement of part of the formation. Absence of thick, channel-form deposits eastward suggests loss of section during emergence. OHIO J. SCI. 88 (1): 23-39, 1988 INTRODUCTION The Bedford Formation (Newberry 1870) is the most The Ohio Shale, Bedford, and Berea Formations of lithologically varied formation of the group. It is com- northern Ohio are clastic units which record prograda- prised of gray and red mudshales, siltstone, and very tional and transgressional events during Late Devonian fine-grained sandstone. The Bedford Formation thins and Early Mississippian time. The sequence of sediments both to the east and west and reaches its maximum is characterized by (1) gray mudshale, clayshale, siltstone, thickness in the Cleveland area. -

Geology of Michigan and the Great Lakes

35133_Geo_Michigan_Cover.qxd 11/13/07 10:26 AM Page 1 “The Geology of Michigan and the Great Lakes” is written to augment any introductory earth science, environmental geology, geologic, or geographic course offering, and is designed to introduce students in Michigan and the Great Lakes to important regional geologic concepts and events. Although Michigan’s geologic past spans the Precambrian through the Holocene, much of the rock record, Pennsylvanian through Pliocene, is miss- ing. Glacial events during the Pleistocene removed these rocks. However, these same glacial events left behind a rich legacy of surficial deposits, various landscape features, lakes, and rivers. Michigan is one of the most scenic states in the nation, providing numerous recre- ational opportunities to inhabitants and visitors alike. Geology of the region has also played an important, and often controlling, role in the pattern of settlement and ongoing economic development of the state. Vital resources such as iron ore, copper, gypsum, salt, oil, and gas have greatly contributed to Michigan’s growth and industrial might. Ample supplies of high-quality water support a vibrant population and strong industrial base throughout the Great Lakes region. These water supplies are now becoming increasingly important in light of modern economic growth and population demands. This text introduces the student to the geology of Michigan and the Great Lakes region. It begins with the Precambrian basement terrains as they relate to plate tectonic events. It describes Paleozoic clastic and carbonate rocks, restricted basin salts, and Niagaran pinnacle reefs. Quaternary glacial events and the development of today’s modern landscapes are also discussed. -

Geology of Fairfield County, Ohio

This dissertation has been 61—5134 microfilmed exactly as received WOLFE, Edward Winslow, 1936- GEOLOGY OF FAIRFIELD COUNTY, OHIO. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1961 Geology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan GEOLOGY OF FAIRFIELD COUNTY, OHIO DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Edward Winslow Wolfe, B. A. The Ohio State University 1961 Approved by Department of Geology ! ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks are due Mr. R. J. Bernhagen, State Geologist, who suggest ed the need for an investigation of the geology of Fairfield County. The writer is particularly indebted to Dr. Aurele La Rooque who di rected the investigation and guided the writer throughout the prepara tion of this report. Many others gave freely of their time in dis cussing with the writer the geology of Fairfield County. Among these, special thanks are due Dr. Jane L. Forsyth of the Ohio Division of Geological Survey, Mr. George J. Franklin, who is presently completing a report on the geology of Licking County, and the writer's colleagues in the Department of Geology at the College of Wooster. The writer thanks several members of the Ohio Division of Geological Survey, in cluding Miss Pauline Smyth, Mr. Karl V. Hoover, and Mr. Harold J. Flint, for their valuable assistance. Most helpful, too, was the as sistance of Mr. Jon S. Galehouse during the summer of i960. The field work was sponsored and financed by the Ohio Division of Geological Survey. Additional financial aid, in the form of a William H. -

Bedrock Maps

1987 BEDROCK GEOLOGY OF MICHIGAN BEDROCK GEOLOGY OF EASTERN UPPER PENINSULA MACKINAC BRECCIA BOIS BLANC FORMATION GARDEN ISLAND FORMATION BASS ISLAND GROUP SALINA GROUP SAINT IGNACE DOLOMITE POINT AUX CHENES SHALE ENGADINE GROUP MANISTIQUE GROUP BURNT BLUFF GROUP KEWEENAW CABOT HEAD SHALE MANITOULIN DOLOMITE QUEENSTON SHALE BIG HILL DOLOMITE HOUGHTON STONINGTON FORMATION UTICA SHALE MEMBER COLLINGWOOD SHALE MEMBER TRENTON GROUP BLACK RIVER GROUP ONTONAGON BARAGA PRAIRIE DU CHIEN GROUP TREMPEALEAU FORMATION MUNISING FORMATION GOGEBIC LU CE MARQUETTE ALGER CHIPPEWA IRON MACKINAC SCHOOLC RAF T DELT A DICKIN SON BEDROCK GEOLOGY OF WESTERN UPPER PENINSULA MACKINAC BRECCIA JACOBSVILLE SANDSTONE EMMET MENOMINEE FREDA SANDSTONE CHEBOYGAN NONESUCH FORMATION PRESQUE ISLE COPPER HARBOR CONGLOMERATE OAK BLUFF FORMATION CHAR LEVOIX PORTAGE LAKE VOLCANICS MONTMORENCY SIEMENS CREEK FORMATION ANT RIM ALPENA INTRUSIVE OTSEGO QUINNESEC FORMATION LEELANAU PAINT RIVER GROUP RIVERTON IRON FORMATION BIJIKI IRON FORMATION GRAND TR AVERSE ALCONA KALKASKA CRAW FOR D OSCOD A NEGAUNEE IRON FORMATION BENZIE IRONWOOD IRON FORMATION DUNN CREEK FORMATION BADWATER GREENSTONE MICHIGAMME FORMATION MANISTEE WEXFORD MISSAUKEE ROSCOMMON OGEMAW IOSCO GOODRICH QUARTZITE HEMLOCK FORMATION BEDROCK GEOLOGY OF ARENAC MENOMINEE & CHOCOLAY GROUPS LOWER PENINSULA EMPEROR VULCANIC COMPLEX MASON LAKE OSCEOLA CLARE GLADWIN SIAMO SLATE & AJIBIK QUARTZITE RED BEDS HURON PALMS FORMATION GRAND RIVER FORMATION CHOCOLAY GROUP SAGINAW FORMATION BAY RANDVILLE DOLOMITE BAYPORT LIMESTONE MICHIGAN -

Beaver Valley, Units 1 & 2, Davis-Besse & Perry, Response To

FENOC 76 South Main Street Fi/rstEn Akron. Ohio 44308 SamuelL. Belcher Senior Vice President and Chief Operating Officer September11,2013 L-13-245 10cFR 50.54(f) ATTN: DocumentControl Desk U.S.Nuclear Regulatory Commission 11555 Rockville Pike Rockville,MD 20852 SUBJECT. BeaverValley Power Station, Unit Nos. 1 and2 DocketNo. 50-334, License No. DPR-66 DocketNo. 50-412, License No. NPF-73 Davis-BesseNuclear Power Station DocketNo. 50-346, License No. NPF-3 PerryNuclear Power Plant DocketNo. 50-440, License No. NPF-58 FirstEnergyNuclear Operatinq Companv (FENOC) Response to NRCRequest for InformationPursuant to 10CFR 50.54(fl Reqarding_the Seismic Aspects of Recommendation2.1 of the Near-TermTask Force (NTTF) Review of Insiqhtsfrom the FukushimaDai-ichi Accident - 1.5Year Response for CEUS Sites On March12,2012, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) issued a fettertitled, "Requestfor InformationPursuant to Title10 of the Codeof FederalRegulations 50.54(f)Regarding Recommendations 2.1, 2.3, and 9.3 of the Near-TermTask Force Reviewof Insightsfrom the FukushimaDai-ichi Accident," to all powerreactor licensees andholders of constructionpermits in activeor deferredstatus. Enclosure 1 of the 10 CFR50.54(0 letter contains a requestfor each addressee in the Centraland Eastern UnitedStates (CEUS) to submita writtenresponse consistent with the requested seismichazard evatuation information (items 1 through7) within 1.5 years of thedate of the 10CFR 50.54(0 letter (by September 12,2013). By letterdated February 15,2013, the NRCendorsed the Electrical Power Research Institute (EPRI) Report 1025287, SersmicEvaluation Guidance: Screening, Prioritization and lmplementationDetails (SPID)for the Resolutionof FukushimaNear-Term Task Force Recommendation 2.1: Seismic,dated November 2012 (hereafter referred to asthe SPID report) Section 4 of theSPID report identifies the detailed information to be included in the seismic hazard evaluationsubmittals BeaverValley Power Station, Unit Nos. -

US EPA Proposal to Reissue an Exemption to AK Steel Corporation

UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY REGION 5 77 WEST JACKSON BOULEVARD CHICAGO, IL 60604-3590 REPLY TO THE ATTENTION OF: WU-16J PROPOSAL TO REISSUE AN EXEMPTION TO AK STEEL CORPORATION FOR THE CONTINUED INJECTION OF HAZARDOUS WASTE SUBJECT TO THE LAND DISPOSAL RESTRICTIONS OF THE HAZARDOUS AND SOLID WASTE AMENDMENTS OF 1984 Action: Notice of Intent to Grant an Exemption for the Injection of Certain Hazardous Wastes to AK Steel Corporation for Two Injection Wells Located at 1801 Crawford Street, Middletown, Ohio. Summary: Through this notice, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA), Region 5, Chicago office, proposes to grant an exemption from the ban on disposal of hazardous wastes through injection wells to AK Steel Corporation (AK Steel) of Middletown, OH. If the exemption is granted, AK Steel may continue to inject hazardous wastes as designated under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), 42 U.S.C. §§ 6901-6992k, by waste code K062 through waste disposal wells UIC Well No. 1 and UIC Well No. 2. On March 6, 2006, AK Steel submitted a petition to the U.S. EPA seeking an exemption from the ban based on a showing under 40 C.F.R. § 148.20(a)(1)(i) that any fluids injected will not migrate vertically out of the injection zone or laterally to a point of discharge or interface with an underground source of drinking water (USDW) within 10,000 years. U.S. EPA has conducted a comprehensive review of the petition, its revisions, and other materials submitted and has determined that the petition submitted by AK Steel, as revised on August 9 and December 12, 2007, meets the requirements of 40 C.F.R. -

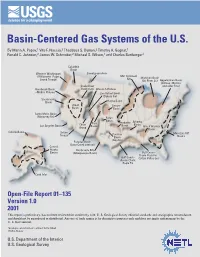

Basin-Centered Gas Systems of the U.S. by Marin A

Basin-Centered Gas Systems of the U.S. By Marin A. Popov,1 Vito F. Nuccio,2 Thaddeus S. Dyman,2 Timothy A. Gognat,1 Ronald C. Johnson,2 James W. Schmoker,2 Michael S. Wilson,1 and Charles Bartberger1 Columbia Basin Western Washington Sweetgrass Arch (Willamette–Puget Mid-Continent Rift Michigan Basin Sound Trough) (St. Peter Ss) Appalachian Basin (Clinton–Medina Snake River and older Fms) Hornbrook Basin Downwarp Wasatch Plateau –Modoc Plateau San Rafael Swell (Dakota Fm) Sacramento Basin Hanna Basin Great Denver Basin Basin Santa Maria Basin (Monterey Fm) Raton Basin Arkoma Park Anadarko Los Angeles Basin Chuar Basin Basin Group Basins Black Warrior Basin Colville Basin Salton Mesozoic Rift Trough Permian Basin Basins (Abo Fm) Paradox Basin (Cane Creek interval) Central Alaska Rio Grande Rift Basins (Albuquerque Basin) Gulf Coast– Travis Peak Fm– Gulf Coast– Cotton Valley Grp Austin Chalk; Eagle Fm Cook Inlet Open-File Report 01–135 Version 1.0 2001 This report is preliminary, has not been reviewed for conformity with U. S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature, and should not be reproduced or distributed. Any use of trade names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U. S. Government. 1Geologic consultants on contract to the USGS 2USGS, Denver U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey BASIN-CENTERED GAS SYSTEMS OF THE U.S. DE-AT26-98FT40031 U.S. Department of Energy, National Energy Technology Laboratory Contractor: U.S. Geological Survey Central Region Energy Team DOE Project Chief: Bill Gwilliam USGS Project Chief: V.F. -

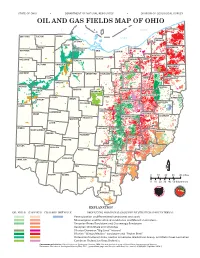

Oil and Gas Fields Map of Ohio

STA5&0'0)*0 t %&PARTMENT OF NA563"-3&4063$&4 t %*7*4*0/0'(&0LOGICAL SUR7EY OIL AND GAS FIELDS MAP OF OHIO ASHTABULA ERIE WILLIAMS FULTON LUCAS LAKE GEAUGA OTTAWA LAKE WOOD TRUMBULL HENRY CUYAHOGA SANDUSKY DEFIANCE ERIE LORAIN PORTAGE HURON MEDINA SUMMIT PAULDING SENECA PUTNAM HANCOCK MAHONING VAN WERT WYANDOT CRAWFORD RICHLAND ASHLAND WAYNE ALLEN STARK COLUMBIANA HARDIN MERCER CARROLL MARION AUGLAIZE HOLMES MORROW TUSCARAWAS KNOX LOGAN JEFFERSON SHELBY UNION COSHOCTON HARRISON DELAWARE DARKE LICKING CHAMPAIGN MIAMI GUERNSEY MUSKINGUM BELMONT FRANKLIN MADISON CLARK PREBLE FAIRFIELD PERRY NOBLE MONTGOMERY MONROE GREENE PICKAWAY MORGAN FAYETTE BUTLER WARREN HOCKING WASHINGTON CLINTON ROSS ATHENS HIGHLAND VINTON HAMILTON CLERMONT PIKE MEIGS JACKSON N BROWN ADAMS GALLIA 0 10 20 30 40 miles SCIOTO 0 10 20 30 40 50 kilometers LAWRENCE EXPLANATION OIL FIELD GAS FIELD COALBED METHANE PRODUCING HORIZON(S) GROUPED BY STRATIGRAPHIC INTERVAL Pennsylvanian undifferentiated sandstones and coals Mississippian undifferentiated sandstones and Maxville Limestone Devonian Berea Sandstone and Cussewago Sandstone Devonian Ohio Shale and siltstones Silurian-Devonian “Big Lime” interval Silurian “Clinton/Medina” sandstone and “Packer Shell” Ordovician fractured shale, Trenton Limestone, Black River Group, and Wells Creek Formation Cambrian-Ordovician Knox Dolomite Recommended citation: Ohio Division of Geological Survey, 2004, Oil and gas fields map of Ohio: Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Geological Survey Map PG-1, generalized page-size version with text, 2 p., scale 1:2,000,000. [Updated 2014.] OIL AND GAS FIELDS MAP OF OHIO Ohio has a rich history of oil-and-gas production that began as a natural seep. It is the trapped occurrences of hydrocarbons nearly 150 years ago. -

Eastern Section American Association of Petroleum Geologists 46Th Annual Meeting Morgantown, West Virginia September 24-27, 2017

Eastern Section American Association of Petroleum Geologists 46th Annual Meeting Morgantown, West Virginia September 24-27, 2017 Program with Abstracts Hosted by: Appalachian Geological Society West Virginia University Department of Geology and Geography With support from the West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey Meeting Sponsors We appreciate your support! Marcellus Level Meeting Sponsors Utica Level Rogersville Level We appreciate your support! Eastern Section American Association of Petroleum Geologists 46th Annual Meeting Morgantown, West Virginia September 24-27, 2017 Program with Abstracts Hosted by: Appalachian Geological Society West Virginia University Department of Geology and Geography With support from the West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey Cover photo used with permission from Jacob Everhart, Canary, LLC Contents Welcome………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………1 2017 Meeting Organizing Committee……………………………………………………………………………….1 Eastern Section AAPG Officers………………………………………………………………………………………….2 Appalachian Geological Society Officers……………………………………………………………………………2 General Information…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….3 Registration Hours……………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Parking………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….….3 Maps………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Exhibits……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……3 Presenters and Judges Room……………………………………………………………………………………..….…3 Presenters, Judges and Session Chairs Breakfast and Information……………………………………3 -

Figure 2 (Pdf)

South North West East West East West East West East Eastern Kentucky Central West Virginia Eastern and Central Ohio Western and Central Pennsylvania Western and Central New York Age Stratigraphy from: Repetski and others (2008) Stratigraphy from: Ryder and others (2008, 2009) Stratigraphy from: Ryder and others (2008, 2009, 2010) Stratigraphy from: Berg and others (1983); Ryder and others (2010) Stratigraphy from: Repetski and others (2008) Era System Series (Ma) Valley Valley Rome Trough Rome Trough Rome Trough and Ridge Bedford Shale and Ridge Cleveland Member Venango Group Catskill Formation 359.2 Upper Devonian strata, undivided Ohio Shale Ohio Three Lick Bed Chagrin Shale equivalent rocks Chagrin Shale Bradford Group Foreknobs Formation Perrysburg Formation Shale Dunkirk Shale Member Huron Member of Ohio Shale Huron Member Elk Group Scherr Formation Upper Dunkirk Shale Java Formation Angola Shale Member Olentangy Shale (upper) Java Formation Java Formation Angola Shale Member West Falls West Falls Brallier Formation West Falls Angola Shale Member Formation Rhinestreet Shale Member Rhinestreet Shale Member of the Formation Rhinestreet Shale Member Formation Rhinestreet Shale Member Upper Devonian strata, undivided West Falls Formation 385.3 Sonyea and Genesee Formations, undivided Sonyea and Genesee Formations, undivided Sonyea and Genesee Formations, undivided Tully Limestone Tully Limestone Tully Limestone Mahantango Formation Mahantango Formation Moscow, Ludlowville, and Skaneateles Shales, undivided Hamilton Olentangy Shale (lower)