FDA Regulation of Alpha-Hydroxy Acids Laura A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nonpharmacological Treatment of Rhinoconjunctivitis and Rhinosinusitis

Journal of Allergy Nonpharmacological Treatment of Rhinoconjunctivitis and Rhinosinusitis Guest Editors: Ralph Mösges, Carlos E. Baena-Cagnani, and Desiderio Passali Nonpharmacological Treatment of Rhinoconjunctivitis and Rhinosinusitis Journal of Allergy Nonpharmacological Treatment of Rhinoconjunctivitis and Rhinosinusitis Guest Editors: Ralph Mosges,¨ Carlos E. Baena-Cagnani, and Desiderio Passali Copyright © 2014 Hindawi Publishing Corporation. All rights reserved. This is a special issue published in “Journal of Allergy.” All articles are open access articles distributed under the Creative Commons At- tribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Editorial Board William E. Berger, USA Alan P. Knutsen, USA Fabienne Ranc, France Kurt Blaser, Switzerland Marek L. Kowalski, Poland Anuradha Ray, USA Eugene R. Bleecker, USA Ting Fan Leung, Hong Kong Harald Renz, Germany JandeMonchy,TheNetherlands Clare M Lloyd, UK Nima Rezaei, Iran Frank Hoebers, The Netherlands Redwan Moqbel, Canada Robert P. Schleimer, USA StephenT.Holgate,UK Desiderio Passali, Italy Massimo Triggiani, Italy Sebastian L. Johnston, UK Stephen P. Peters, USA Hugo Van Bever, Singapore Young J. Juhn, USA David G. Proud, Canada Garry Walsh, United Kingdom Contents Nonpharmacological Treatment of Rhinoconjunctivitis and Rhinosinusitis,RalphMosges,¨ Carlos E. Baena-Cagnani, and Desiderio Passali Volume 2014, Article ID 416236, 2 pages Clinical Efficacy of a Spray Containing Hyaluronic Acid and Dexpanthenol after Surgery in the Nasal Cavity (Septoplasty, Simple Ethmoid Sinus Surgery, and Turbinate Surgery), Ina Gouteva, Kija Shah-Hosseini, and Peter Meiser Volume 2014, Article ID 635490, 10 pages The Effectiveness of Acupuncture Compared to Loratadine in Patients Allergic to House Dust ,Mites Bettina Hauswald, Christina Dill, Jurgen¨ Boxberger, Eberhard Kuhlisch, Thomas Zahnert, and Yury M. -

(CD-P-PH/PHO) Report Classification/Justifica

COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS ON THE CLASSIFICATION OF MEDICINES AS REGARDS THEIR SUPPLY (CD-P-PH/PHO) Report classification/justification of medicines belonging to the ATC group R01 (Nasal preparations) Table of Contents Page INTRODUCTION 5 DISCLAIMER 7 GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THIS DOCUMENT 8 ACTIVE SUBSTANCES Cyclopentamine (ATC: R01AA02) 10 Ephedrine (ATC: R01AA03) 11 Phenylephrine (ATC: R01AA04) 14 Oxymetazoline (ATC: R01AA05) 16 Tetryzoline (ATC: R01AA06) 19 Xylometazoline (ATC: R01AA07) 20 Naphazoline (ATC: R01AA08) 23 Tramazoline (ATC: R01AA09) 26 Metizoline (ATC: R01AA10) 29 Tuaminoheptane (ATC: R01AA11) 30 Fenoxazoline (ATC: R01AA12) 31 Tymazoline (ATC: R01AA13) 32 Epinephrine (ATC: R01AA14) 33 Indanazoline (ATC: R01AA15) 34 Phenylephrine (ATC: R01AB01) 35 Naphazoline (ATC: R01AB02) 37 Tetryzoline (ATC: R01AB03) 39 Ephedrine (ATC: R01AB05) 40 Xylometazoline (ATC: R01AB06) 41 Oxymetazoline (ATC: R01AB07) 45 Tuaminoheptane (ATC: R01AB08) 46 Cromoglicic Acid (ATC: R01AC01) 49 2 Levocabastine (ATC: R01AC02) 51 Azelastine (ATC: R01AC03) 53 Antazoline (ATC: R01AC04) 56 Spaglumic Acid (ATC: R01AC05) 57 Thonzylamine (ATC: R01AC06) 58 Nedocromil (ATC: R01AC07) 59 Olopatadine (ATC: R01AC08) 60 Cromoglicic Acid, Combinations (ATC: R01AC51) 61 Beclometasone (ATC: R01AD01) 62 Prednisolone (ATC: R01AD02) 66 Dexamethasone (ATC: R01AD03) 67 Flunisolide (ATC: R01AD04) 68 Budesonide (ATC: R01AD05) 69 Betamethasone (ATC: R01AD06) 72 Tixocortol (ATC: R01AD07) 73 Fluticasone (ATC: R01AD08) 74 Mometasone (ATC: R01AD09) 78 Triamcinolone (ATC: R01AD11) 82 -

Prediction of Premature Termination Codon Suppressing Compounds for Treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Using Machine Learning

Prediction of Premature Termination Codon Suppressing Compounds for Treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy using Machine Learning Kate Wang et al. Supplemental Table S1. Drugs selected by Pharmacophore-based, ML-based and DL- based search in the FDA-approved drugs database Pharmacophore WEKA TF 1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3- 5-O-phosphono-alpha-D- (phospho-rac-(1-glycerol)) ribofuranosyl diphosphate Acarbose Amikacin Acetylcarnitine Acetarsol Arbutamine Acetylcholine Adenosine Aldehydo-N-Acetyl-D- Benserazide Acyclovir Glucosamine Bisoprolol Adefovir dipivoxil Alendronic acid Brivudine Alfentanil Alginic acid Cefamandole Alitretinoin alpha-Arbutin Cefdinir Azithromycin Amikacin Cefixime Balsalazide Amiloride Cefonicid Bethanechol Arbutin Ceforanide Bicalutamide Ascorbic acid calcium salt Cefotetan Calcium glubionate Auranofin Ceftibuten Cangrelor Azacitidine Ceftolozane Capecitabine Benserazide Cerivastatin Carbamoylcholine Besifloxacin Chlortetracycline Carisoprodol beta-L-fructofuranose Cilastatin Chlorobutanol Bictegravir Citicoline Cidofovir Bismuth subgallate Cladribine Clodronic acid Bleomycin Clarithromycin Colistimethate Bortezomib Clindamycin Cyclandelate Bromotheophylline Clofarabine Dexpanthenol Calcium threonate Cromoglicic acid Edoxudine Capecitabine Demeclocycline Elbasvir Capreomycin Diaminopropanol tetraacetic acid Erdosteine Carbidopa Diazolidinylurea Ethchlorvynol Carbocisteine Dibekacin Ethinamate Carboplatin Dinoprostone Famotidine Cefotetan Dipyridamole Fidaxomicin Chlormerodrin Doripenem Flavin adenine dinucleotide -

Hyaluronic Acid Introduced 2003

Hyaluronic Acid Introduced 2003 What Is It? Are There Any Potential Drug Interactions? Hyaluronic acid, or HA, is a naturally occurring polymer found in every tissue of At this time, there are no known adverse reactions when taken in conjunction the body. It is particularly concentrated in the skin (almost 50% of all HA in the with medications. body is found in the skin) and synovial fluid. It is composed of alternating units of n-acetyl-d-glucosamine and d-glucuronate. This polymer’s functions include Hyaluronic acid attracting and retaining water in the extracellular matrix of tissues, in layers of skin, and in synovial fluid.* each vegetarian capsule contains v 3 hyaluronic acid (low molecular weight) ..............................................................................70 mg Features Include other ingredients: hypo-allergenic plant fiber (cellulose), vegetarian capsule (cellulose, water) 1–2 capsules per day, in divided doses, with or between meals. Clinically Researched Absorption: In nature, HA is a large molecular weight compound, ranging in size from 500,000-6,000,000 daltons. This is too large to ® be absorbed in the small intestines. HyaMax sodium hyaluronate provides a Hyaluronic acid liquid low molecular weight source of hyaluronic acid produced through fermentation. ® In a pharmacokinetic study, orally administered HyaMax hyaluronic acid was 2 ml (0.06 fl oz) (2 full droppers) contains v incorporated into joints, connective tissue and skin, with a particular affinity for hyaluronic acid (low molecular weight) ..............................................................................10 mg cartilaginous joints.* other ingredients: purified water, apple juice concentrate, citric acid, natural apple flavor, potassium sorbate, purified stevia extract Uses For Hyaluronic Acid serving size: 2 ml (0.06 fl oz) Skin Health: For skin cells, the ability of HA to attract and retain water is servings per container: 29 essential for proper cell-to-cell communication, hydration, nutrient delivery, and 1-2 servings daily, with or between meals. -

Bulk Drug Substances Under Evaluation for Section 503A

Updated July 1, 2020 Bulk Drug Substances Nominated for Use in Compounding Under Section 503A of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act Includes three categories of bulk drug substances: • Category 1: Bulk Drug Substances Under Evaluation • Category 2: Bulk Drug Substances that Raise Significant Safety Concerns • Category 3: Bulk Drug Substances Nominated Without Adequate Support Updates to Section 503A Categories • Removal from category 3 o Artesunate – This bulk drug substance is a component of an FDA-approved drug product (NDA 213036) and compounded drug products containing this substance may be eligible for the exemptions under section 503A of the FD&C Act pursuant to section 503A(b)(1)(A)(i)(II). This change will be effective immediately and will not have a waiting period. For more information, please see the Interim Policy on Compounding Using Bulk Drug Substances Under Section 503A and the final rule on bulk drug substances that can be used for compounding under section 503A, which became effective on March 21, 2019. 1 Updated July 1, 2020 503A Category 1 – Bulk Drug Substances Under Evaluation • 7 Keto Dehydroepiandrosterone • Glycyrrhizin • Acetyl L Carnitine/Acetyl-L- carnitine • Kojic Acid Hydrochloride • L-Citrulline • Alanyl-L-Glutamine • Melatonin • Aloe Vera/ Aloe Vera 200:1 Freeze Dried • Methylcobalamin • Alpha Lipoic Acid • Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) • Artemisia/Artemisinin • Nettle leaf (Urtica dioica subsp. dioica leaf) • Astragalus Extract 10:1 • Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (NAD) • Boswellia • Nicotinamide -

Intra-Articular Corticosteroid and Hyaluronic Acid Injections in the Management of Osteoarthritis

78 Review / Derleme Intra-Articular Corticosteroid and Hyaluronic Acid Injections in the Management of Osteoarthritis Osteoartrit Tedavisinde ‹ntraartiküler Kortikosteroid ve Hyaluronik Asit Enjeksiyonlar› G. Guy VANDERSTRAETEN, Martine De MUYNCK, Luc Vanden BOSCCHE, Tina DECORTE Ghent University Hospital, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Ghent, Belgium Summary Özet Intra-articular corticosteroid injections have long been used to treat oste- Eklem içi kortikosteroid enjeksiyonlar› osteoartrit tedavisinde uzun sü- oarthritis, whereas intra-articular hyaluronic acid injections for only a few reden beri kullan›lmaktad›r. Oysa eklem içi hyaluronik asit injeksiyonlar› years. In the literature, evidence-based reports on the efficacy of these sadece son y›llarda kullan›l›r hale gelmifltir. Literatürde bu ajanlar›n et- compounds are non-existent. In the presence of acute hydrops in an oste- kinli¤i aç›s›ndan kan›ta dayal› raporlar bulunmamaktad›r. Osteoartritli oarthritic knee an intra-articular corticosteroid injection following aspirati- bir dizde akut efüzyon varl›¤›nda eklemden aspirasyonu takiben eklem on of the joint can be considered. A maximum of 3 injections can be admi- içi kortikosteroid uygulamas› düflünülebilir. 8-10 günlük aralar ile en faz- nistered at intervals of 8 to 10 days, to be repeated every 6 months if ab- la 3 enjeksiyon uygulanabilir ve e¤er çok gerekli ise her 6 ayda bir tek- solutely necessary. A patient with a dry and painful osteoarthritic knee can rarlanabilir. Kuru ve a¤r›l› bir diz ise haftal›k aralar ile uygulanan eklem be a candidate for intra-articular hyaluronic acid injections at weekly inter- içi hyaluronik asit enjeksiyonu için aday olabilir. -

Features CSA Outpatient Prescription Formulary

FY2014 Cancer State Aid Supportive Therapies Formulary Out-Patient Prescriptions Formulary Prescription Notes To qualify for reimbursement, medications must be related to the treatment of the patient's cancer or cancer symptoms. Medications for conditions not related to the patient's cancer treatment or related symptoms are not eligible for program reimbursements. If available, generic equivalents must be used. Reimbursement will only be made for brand name drugs if there is no generic equivalent. Over-the-counter medication and strengths of medication will not be approved. For compounds, reimbursement will be made only for the amount of actual medication dispensed. All prescription medications require written and Cancer State Aid (CSA) signed prior approval on a current CSA Medication Request Form. In addition to prior approval, any medications not included on this list will require additional medical and/or financial review. Approvals of requested prescriptions and refills are limited to time periods which do not extend beyond the current state fiscal year (FY), as patient enrollments are limited to the current FY. Each State FY begins on July 1st and ends on the following June 30th. Antibiotics/Antifungals Recommended Duration of Therapy - limited to 30 days Generic Name Brand Name Amoxicillin Amoxil, Trimox Amoxicillin/clavulanate Augmentin Ampicillin Principen Azithromycin Z-Pak Cefadroxil Duricef Cefdinir Omnicef Cefuroxime Ceftin Cephalexin Keflex Ciprofloxacin Cipro Clarithromycin Biaxin Clindamycin Cleocin Clotrimazole Mycelex Dapsone Dapsone Doxycycline Doryx, Monodox, Vibra-tabs Erythromycin Eryc, Ery-tab, PCE, E.E.S. Ethambutol Myambutol Fluconazole Diflucan Gatifloxacin Tequin Ketoconazole Nizoral Levofloxacin Levaquin Metronidazole Flagyl Moxifloxacin Avelox Mupirocin Bactroban Neomycin Various combinations Rev. -

Høring Vedrørende Indstilling Til Kommissionens Lister Over Lægemidler, Der Omfattes Af Eller Undtages Fra Kravet Om Sikkerhedsforanstaltninger / Safety Features

Høring vedrørende indstilling til Kommissionens lister over lægemidler, der omfattes af eller undtages fra kravet om sikkerhedsforanstaltninger / safety features Sundhedsstyrelsen beder hermed om kommentarer og eventuelle yderligere oplysninger til udkast til liste over godkendte receptpligtige lægemidler der 4. september 2014 påtænkes indstillet til Europa Kommissionen med henblik på undtagelse fra Sagsnr. LMST 2014083346 kravet om sikkerhedsforanstaltninger (hvid liste ). Annex 1. Reference MBK E [email protected] Endvidere beder vi om oplysninger om hvilke godkendte ikke-receptpligtige lægemidler, der tidligere har været forfalsket og derfor skal omfattes af kravet om sikkerhedsforanstaltninger (sort liste ). Annex 2. Krav om sikkerhedsforanstaltninger på lægemidler Europa-Parlamentets og Rådets direktiv 2011/62 1 om ændring af direktiv 2001/83 2 om oprettelse af en fællesskabskodeks for humanmedicinske lægemidler for så vidt angår forhindring af, at forfalskede lægemidler kommer ind i den lovlige forsyningskæde, indfører sikkerhedsforanstaltninger på visse lægemidler. Direktivet indfører to former for sikkerhedsforanstaltninger på den ydre pakning på visse lægemidler med undtagelse af radioaktive lægemidler. Det fremgår således af artikel 54(o) i direktiv 2001/83, at sikkerhedsforanstaltningerne skal gøre det muligt, dels at kontrollere lægemidlets ægthed og identificere individuelle pakninger (en unik identifikator), dels at kontrollere om lægemidlets ydre emballage har været brudt (en anbrudsanordning). Kontrollen af sikkerhedsforanstaltningerne -

Vr Meds Ex01 3B 0825S Coding Manual Supplement Page 1

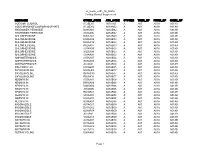

vr_meds_ex01_3b_0825s Coding Manual Supplement MEDNAME OTHER_CODE ATC_CODE SYSTEM THER_GP PHRM_GP CHEM_GP SODIUM FLUORIDE A12CD01 A01AA01 A A01 A01A A01AA SODIUM MONOFLUOROPHOSPHATE A12CD02 A01AA02 A A01 A01A A01AA HYDROGEN PEROXIDE D08AX01 A01AB02 A A01 A01A A01AB HYDROGEN PEROXIDE S02AA06 A01AB02 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE B05CA02 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE D08AC02 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE D09AA12 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE R02AA05 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S01AX09 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S02AA09 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S03AA04 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B A07AA07 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B G01AA03 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B J02AA01 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB POLYNOXYLIN D01AE05 A01AB05 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE D08AH03 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE G01AC30 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE R02AA14 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN A07AA01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN B05CA09 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN D06AX04 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN J01GB05 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN R02AB01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S01AA03 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S02AA07 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S03AA01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE A07AC01 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE D01AC02 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE G01AF04 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE J02AB01 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE S02AA13 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB NATAMYCIN A07AA03 A01AB10 A A01 -

Hyaluronic Acid Derivatives

Hyaluronic Acid Derivatives When requesting hyaluronic acid intra-articular products, the individual requiring treatment must be diagnosed with the following FDA-approved indication and meet the specific coverage guidelines and applicable safety criteria for the covered indications. The following hyaluronic acid intra-articular products are included in this policy: Hyalgan® (sodium hyaluronate), Supartz FX® (sodium hyaluronate), Hymovis® (hyaluronan), Euflexxa® (sodium hyaluronate), Orthovisc ® (hyaluronan), Synvisc® (hylan G-F 20), Synvisc-One® (hylan G-F 20), Gel-One® (sodium hyaluronate), Monovisc® (hyaluronan), Gel-Syn® 3 (sodium hyaluronate), Genvisc® 850 (sodium hyaluronate), Durolane® (sodium hyaluronate), TriVisc® (sodium hyaluronate), Synojoynt (sodium hyaluronate), and Visco-3® (sodium hyaluronate). FDA-approved indication • Indicated for the treatment of pain in osteoarthritis of the knee in individuals who have failed to respond adequately to conservative non-pharmacologic therapy and analgesics (eg, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen). Coverage Guidelines Osteoarthritis (OA) of the Knee The patient must meet all the following conditions for initial approval: • Diagnosis of the knee to be treated is confirmed by radiological evidence of knee OA (e.g., x-ray, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], computed tomography [CT] scan, ultrasound) • The patient has tried at least TWO of the following three modalities of therapy for OA: o At least one course of physical therapy (PT) for knee OA; OR o At least TWO of the following pharmacological therapies: . Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), oral or topical (examples of oral agents include naproxen, ibuprofen, Celebrex; examples of topical NSAIDs include: diclofenac solution or gel). [NOTE: a trial of two or more NSAIDs {oral and/or topical} counts as one pharmacological therapy] . -

Alphabetical Listing of ATC Drugs & Codes

Alphabetical Listing of ATC drugs & codes. Introduction This file is an alphabetical listing of ATC codes as supplied to us in November 1999. It is supplied free as a service to those who care about good medicine use by mSupply support. To get an overview of the ATC system, use the “ATC categories.pdf” document also alvailable from www.msupply.org.nz Thanks to the WHO collaborating centre for Drug Statistics & Methodology, Norway, for supplying the raw data. I have intentionally supplied these files as PDFs so that they are not quite so easily manipulated and redistributed. I am told there is no copyright on the files, but it still seems polite to ask before using other people’s work, so please contact <[email protected]> for permission before asking us for text files. mSupply support also distributes mSupply software for inventory control, which has an inbuilt system for reporting on medicine usage using the ATC system You can download a full working version from www.msupply.org.nz Craig Drown, mSupply Support <[email protected]> April 2000 A (2-benzhydryloxyethyl)diethyl-methylammonium iodide A03AB16 0.3 g O 2-(4-chlorphenoxy)-ethanol D01AE06 4-dimethylaminophenol V03AB27 Abciximab B01AC13 25 mg P Absorbable gelatin sponge B02BC01 Acadesine C01EB13 Acamprosate V03AA03 2 g O Acarbose A10BF01 0.3 g O Acebutolol C07AB04 0.4 g O,P Acebutolol and thiazides C07BB04 Aceclidine S01EB08 Aceclidine, combinations S01EB58 Aceclofenac M01AB16 0.2 g O Acefylline piperazine R03DA09 Acemetacin M01AB11 Acenocoumarol B01AA07 5 mg O Acepromazine N05AA04 -

Anatomical Classification Guidelines V2021 EPHMRA ANATOMICAL CLASSIFICATION GUIDELINES 2021

EPHMRA ANATOMICAL CLASSIFICATION GUIDELINES 2021 Anatomical Classification Guidelines V2021 "The Anatomical Classification of Pharmaceutical Products has been developed and maintained by the European Pharmaceutical Marketing Research Association (EphMRA) and is therefore the intellectual property of this Association. EphMRA's Classification Committee prepares the guidelines for this classification system and takes care for new entries, changes and improvements in consultation with the product's manufacturer. The contents of the Anatomical Classification of Pharmaceutical Products remain the copyright to EphMRA. Permission for use need not be sought and no fee is required. We would appreciate, however, the acknowledgement of EphMRA Copyright in publications etc. Users of this classification system should keep in mind that Pharmaceutical markets can be segmented according to numerous criteria." © EphMRA 2021 Anatomical Classification Guidelines V2021 CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 1 B BLOOD AND BLOOD FORMING ORGANS 28 C CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM 36 D DERMATOLOGICALS 51 G GENITO-URINARY SYSTEM AND SEX HORMONES 58 H SYSTEMIC HORMONAL PREPARATIONS (EXCLUDING SEX HORMONES) 68 J GENERAL ANTI-INFECTIVES SYSTEMIC 72 K HOSPITAL SOLUTIONS 88 L ANTINEOPLASTIC AND IMMUNOMODULATING AGENTS 96 M MUSCULO-SKELETAL SYSTEM 106 N NERVOUS SYSTEM 111 P PARASITOLOGY 122 R RESPIRATORY SYSTEM 124 S SENSORY ORGANS 136 T DIAGNOSTIC AGENTS 143 V VARIOUS 145 Anatomical Classification Guidelines V2021 INTRODUCTION The Anatomical Classification was initiated in 1971 by EphMRA. It has been developed jointly by Intellus/PBIRG and EphMRA. It is a subjective method of grouping certain pharmaceutical products and does not represent any particular market, as would be the case with any other classification system.