Conasauga River Alliance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stream-Temperature Characteristics in Georgia

STREAM-TEMPERATURE CHARACTERISTICS IN GEORGIA By T.R. Dyar and S.J. Alhadeff ______________________________________________________________________________ U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 96-4203 Prepared in cooperation with GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION DIVISION Atlanta, Georgia 1997 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Charles G. Groat, Director For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services 3039 Amwiler Road, Suite 130 Denver Federal Center Peachtree Business Center Box 25286 Atlanta, GA 30360-2824 Denver, CO 80225-0286 CONTENTS Page Abstract . 1 Introduction . 1 Purpose and scope . 2 Previous investigations. 2 Station-identification system . 3 Stream-temperature data . 3 Long-term stream-temperature characteristics. 6 Natural stream-temperature characteristics . 7 Regression analysis . 7 Harmonic mean coefficient . 7 Amplitude coefficient. 10 Phase coefficient . 13 Statewide harmonic equation . 13 Examples of estimating natural stream-temperature characteristics . 15 Panther Creek . 15 West Armuchee Creek . 15 Alcovy River . 18 Altamaha River . 18 Summary of stream-temperature characteristics by river basin . 19 Savannah River basin . 19 Ogeechee River basin. 25 Altamaha River basin. 25 Satilla-St Marys River basins. 26 Suwannee-Ochlockonee River basins . 27 Chattahoochee River basin. 27 Flint River basin. 28 Coosa River basin. 29 Tennessee River basin . 31 Selected references. 31 Tabular data . 33 Graphs showing harmonic stream-temperature curves of observed data and statewide harmonic equation for selected stations, figures 14-211 . 51 iii ILLUSTRATIONS Page Figure 1. Map showing locations of 198 periodic and 22 daily stream-temperature stations, major river basins, and physiographic provinces in Georgia. -

List of TMDL Implementation Plans with Tmdls Organized by Basin

Latest 305(b)/303(d) List of Streams List of Stream Reaches With TMDLs and TMDL Implementation Plans - Updated June 2011 Total Maximum Daily Loadings TMDL TMDL PLAN DELIST BASIN NAME HUC10 REACH NAME LOCATION VIOLATIONS TMDL YEAR TMDL PLAN YEAR YEAR Altamaha 0307010601 Bullard Creek ~0.25 mi u/s Altamaha Road to Altamaha River Bio(sediment) TMDL 2007 09/30/2009 Altamaha 0307010601 Cobb Creek Oconee Creek to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Cobb Creek Oconee Creek to Altamaha River FC 2012 Altamaha 0307010601 Milligan Creek Uvalda to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 2006 Altamaha 0307010601 Milligan Creek Uvalda to Altamaha River FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Oconee Creek Headwaters to Cobb Creek DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Oconee Creek Headwaters to Cobb Creek FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010602 Ten Mile Creek Little Ten Mile Creek to Altamaha River Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010602 Ten Mile Creek Little Ten Mile Creek to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010603 Beards Creek Spring Branch to Altamaha River Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010603 Five Mile Creek Headwaters to Altamaha River Bio(sediment) TMDL 2007 09/30/2009 Altamaha 0307010603 Goose Creek U/S Rd. S1922(Walton Griffis Rd.) to Little Goose Creek FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010603 Mushmelon Creek Headwaters to Delbos Bay Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010604 Altamaha River Confluence of Oconee and Ocmulgee Rivers to ITT Rayonier -

Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards ( 1) Purpose. The establishment of water quality standards. (2) W ate r Quality Enhancement: (a) The purposes and intent of the State in establishing Water Quality Standards are to provide enhancement of water quality and prevention of pollution; to protect the public health or welfare in accordance with the public interest for drinking water supplies, conservation of fish, wildlife and other beneficial aquatic life, and agricultural, industrial, recreational, and other reasonable and necessary uses and to maintain and improve the biological integrity of the waters of the State. ( b) The following paragraphs describe the three tiers of the State's waters. (i) Tier 1 - Existing instream water uses and the level of water quality necessary to protect the existing uses shall be maintained and protected. (ii) Tier 2 - Where the quality of the waters exceed levels necessary to support propagation of fish, shellfish, and wildlife and recreation in and on the water, that quality shall be maintained and protected unless the division finds, after full satisfaction of the intergovernmental coordination and public participation provisions of the division's continuing planning process, that allowing lower water quality is necessary to accommodate important economic or social development in the area in which the waters are located. -

Assessing Climate-Change-Induced Flood Risk in the Conasauga River

Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 21, 1739–1757, 2021 https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-21-1739-2021 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Assessing climate-change-induced flood risk in the Conasauga River watershed: an application of ensemble hydrodynamic inundation modeling Tigstu T. Dullo1, George K. Darkwah1, Sudershan Gangrade2,3, Mario Morales-Hernández3,4, M. Bulbul Sharif5, Alfred J. Kalyanapu1, Shih-Chieh Kao2,3, Sheikh Ghafoor5, and Moetasim Ashfaq3,4 1Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Tennessee Technological University, Cookeville, TN 38505, USA 2Environmental Sciences Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, TN 37831, USA 3Climate Change Science Institute, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, TN 37831, USA 4Computational Sciences and Engineering Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, TN 37831, USA 5Department of Computer Science, Tennessee Technological University, Cookeville, TN 38505, USA Correspondence: Alfred J. Kalyanapu ([email protected]) Received: 13 October 2020 – Discussion started: 20 October 2020 Revised: 7 April 2021 – Accepted: 18 April 2021 – Published: 2 June 2021 Abstract. This study evaluates the impact of potential future Copyright statement. This paper has been authored by UT-Battelle, climate change on flood regimes, floodplain protection, and LLC, under contract DE-AC05-00OR22725 with the US Depart- electricity infrastructures across the Conasauga River wa- ment of Energy (DOE). The US government retains and the pub- tershed in the southeastern United States through ensemble lisher, by accepting the article for publication, acknowledges that hydrodynamic inundation modeling. The ensemble stream- the US government retains a nonexclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, flow scenarios were simulated by the Distributed Hydrol- worldwide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this paper, or allow others to do so, for US government purposes. -

Benefits of Water Trails

National Park Service Rivers, Trails & Conservation Assistance Program Southeast Regional Office--Atlanta Recreation Conservation Low investment Revenue generators Georgia has a variety of water resources--lakes, rivers and the coast. Each offers a different kind of opportunity for healthy outdoor activity In the U.S., participation increased 117% from 1995-2005. Water trails provide recreational opportunities for all sizes and ages- -children, adults, seniors. Water quality & quantity Wildlife Land use Canoe trails make connections between land, water, riparian edges and wildlife habitats. Canoe trails create environmental stewards. They are a constituency that understands land use & watershed issues. Upstream issues = downstream problems. And paddle groups such as Georgia Canoe Association sponsor clean-ups of rivers. The economics of the trail implementation: Inexpensive relative to other recreation projects. Not as much land to buy or structures to build. Access facilities can be minimal and inexpensive. Existing public land and facilities on rivers, lakes and the coast. Revenue generation from the canoe trail: Increased spending in the local area. Existing businesses increase profits-- restaurants, outfitters, lodging . New businesses develop to support the trail. Purchases of gear & equipment increase and support business. Festivals and events around the trail support the local community. More value from local government support. Improve local community with higher quality of life & improved tax base. Altamaha River www.altmahariver.org trail starts near the end of the Ocmulgee river and goes to Darien. City of Canton—Greenway Master Plan (2000) includes blueway. Will become part of the Etowah River Blueway. Chattahoochee Canoe Trail –Upper section (proposed)—about 40 miles from Sautee Creek to Clarks Bridge at Lake Lanier. -

GEORGIA TROUT FISHING REGULATIONS Trout Season Trout

GEORGIA TROUT FISHING REGULATIONS Trout Season All designated trout waters are now open year round. Trout Fishing Hours • Fishing 24 hours a day is allowed on all trout streams and all impoundments on trout streams except those in the next paragraph. • Fishing hours on Dockery Lake, Rock Creek Lake, the Chattahoochee River from Buford Dam to Peachtree Creek, the Conasauga River watershed upstream of the Georgia-Tennessee state line and Smith Creek downstream of Unicoi dam are 30 minutes before sunrise until 30 minutes after sunset. Night fishing is not allowed. Trout Fishing Rules • Trout anglers are restricted to the use of one pole and line which must be hand held. No other type of gear may be used in trout streams. • It is unlawful to use live fish for bait in trout streams. Seining bait-fish is not allowed in any trout stream. Impoundments On Trout Streams Anglers can: • Fish for fish species other than trout without a trout license on Dockery and Rock Creek lakes. • Fish at night, except on Dockery and Rock Creek lakes. See Trout Fishing Hours for details. Impoundment notes: • If you fish for or possess trout, you must possess a trout license. If you catch a trout and do not possess a trout license you must release the trout immediately. • State park visitors are not required to have a trout license to fish in the impounded waters of the Park. However, those visitors wishing to harvest trout will need to have a trout license in their possession. Delayed Harvest Streams Anglers fishing delayed harvest streams must release all trout immediately and use and possess only artificial lures with one single hook per lure from Nov. -

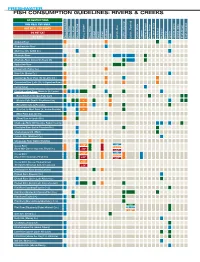

Fish Consumption Guidelines: Rivers & Creeks

FRESHWATER FISH CONSUMPTION GUIDELINES: RIVERS & CREEKS NO RESTRICTIONS ONE MEAL PER WEEK ONE MEAL PER MONTH DO NOT EAT NO DATA Bass, LargemouthBass, Other Bass, Shoal Bass, Spotted Bass, Striped Bass, White Bass, Bluegill Bowfin Buffalo Bullhead Carp Catfish, Blue Catfish, Channel Catfish,Flathead Catfish, White Crappie StripedMullet, Perch, Yellow Chain Pickerel, Redbreast Redhorse Redear Sucker Green Sunfish, Sunfish, Other Brown Trout, Rainbow Trout, Alapaha River Alapahoochee River Allatoona Crk. (Cobb Co.) Altamaha River Altamaha River (below US Route 25) Apalachee River Beaver Crk. (Taylor Co.) Brier Crk. (Burke Co.) Canoochee River (Hwy 192 to Lotts Crk.) Canoochee River (Lotts Crk. to Ogeechee River) Casey Canal Chattahoochee River (Helen to Lk. Lanier) (Buford Dam to Morgan Falls Dam) (Morgan Falls Dam to Peachtree Crk.) * (Peachtree Crk. to Pea Crk.) * (Pea Crk. to West Point Lk., below Franklin) * (West Point dam to I-85) (Oliver Dam to Upatoi Crk.) Chattooga River (NE Georgia, Rabun County) Chestatee River (below Tesnatee Riv.) Chickamauga Crk. (West) Cohulla Crk. (Whitfield Co.) Conasauga River (below Stateline) <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (River Mile Zero to Hwy 100, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (Hwy 100 to Stateline, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" Coosa River (Coosa, Etowah below <20" Thompson-Weinman dam, Oostanaula) ≥20" Coosawattee River (below Carters) Etowah River (Dawson Co.) Etowah River (above Lake Allatoona) Etowah River (below Lake Allatoona dam) Flint River (Spalding/Fayette Cos.) Flint River (Meriwether/Upson/Pike Cos.) Flint River (Taylor Co.) Flint River (Macon/Dooly/Worth/Lee Cos.) <16" Flint River (Dougherty/Baker Mitchell Cos.) 16–30" >30" Gum Crk. -

Extreme Drought: Summary of Hydrologic Conditions in Georgia, 2012 the U.S

Extreme Drought: Summary of Hydrologic Conditions in Georgia, 2012 The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamflow and Groundwater Data WYs 1999–2012 can be accessed online at Georgia Water Science Center (GaWSC) http://ga.water.usgs.gov/publications/pubswdr. maintains a long-term hydrologic monitoring Daily, monthly, and yearly streamflow html. A digital map at http://maps.waterdata. network of more than 330 real-time stream- statistics from the 2012 USGS annual data usgs.gov allows the user to search for current gages, including 10 real-time lake-level report (ADR; U.S. Geological Survey, 2012a) and historical data and graphics collected as monitoring stations, 63 real-time water-quality were used to develop this summary. Data for part of the USGS monitoring network. monitors, and 48 water-quality sampling stations. Additionally, the GaWSC operates more than 180 groundwater monitoring wells, Quarterly Hydrologic Conditions in Georgia for 2012 WY, Based on Drainage Basin Runoff 42 of which are real-time. One of the many D. 07/01/12– EXPLANATION benefits from this monitoring network is that A. 10/01/11– B. 01/01/12– C. 04/01/12– 09/30/12 Percentile classes the data analyses provide a well distributed 12/31/11 03/30/12 06/30/12 Highest overview of the hydrologic conditions of creeks, Much above normal, >90 rivers, reservoirs, and aquifers in Georgia. Above normal, 76 to 90 Streamflow and groundwater data are GEORGIA Normal, 25 to 75 verified throughout the year by USGS hydro Below normal, 10 to 24 graphers, and this information is available to Much below normal <10 water-resource managers, recreationalists, and Lowest Federal, State, and local agencies. -

Total Maximum Daily Load Evaluation for Fifty-Eight Stream Segments in the Coosa River Basin for Fecal Coliform

Total Maximum Daily Load Evaluation for Fifty-Eight Stream Segments in the Coosa River Basin for Fecal Coliform Submitted to: The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 4 Atlanta, Georgia Submitted by: The Georgia Department of Natural Resources Environmental Protection Division Atlanta, Georgia January 2004 Total Maximum Daily Load Evaluation January 2004 Coosa River Basin (Fecal coliform) Table of Contents Section Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................. iv 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Watershed Description......................................................................................................1 1.3 Water Quality Standard.....................................................................................................9 2.0 WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT ...................................................................................... 15 3.0 SOURCE ASSESSMENT .................................................................................................... 16 3.1 Point Source Assessment ............................................................................................... 16 3.2 Nonpoint Source Assessment........................................................................................ -

Mississippi Period Archaeology of the Georgia Valley and Ridge Province

UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA Laboratory of Archaeology Series Report No. 25 Georgia Archaeological Research Design Paper, No. 4 MISSISSIPPI PERIOD ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE GEORGIA VALLEY AND RIDGE PROVINCE By David J. Hally Department of Anthropology University of Georgia and James B. Langford, Jr. The Coosawattee Foundation 1988 Reprinted, 1995 For John Wear, energetic pioneer in the archaeology of northwest Georgia TABLE OF CONTENTS FIGJRFS. • • . • . • . • • • • • . • . • • • • . • • . • . • . • . • . • . • • . • . • vi TABLES. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •• vii .ACID\1~~ • ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• • viii INTRODUcrION ••••••••••• 1 THE VALLEY MlD RIDGE PROVINCE 2 PREVIOUS ARCHAEDLOGICAL RESEARCH IN THE VALLEY AND RIDGE PROVINCE •••••••••••••••••.••••••••• 13 PREHISTORIC OVERVIEW ••••••••••• 22 EARLY MISSISSIPPI PERIOD {A.D. 900-1200) •••••••• 41 MIDDLE tlISSISSIPPI PERIOD {A.D. 1200-1350) •••••••••• 55 LATE MISSISSIPPI PERIOD (A.D. 1350-1540) •••••••••••• 67 HESOURCE MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS 82 THE CULTURAL RESOURCES 82 RESEARCH PROBLEMS IN VALLEY AND RIJ::x:;E PROVINCE I~SSISSIPPIAN ARCHAIDLOGY ••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 86 RESOURCE SIGf.\!IFICANCE 92 PRESERVING ARCHAIDLOGICAL RESOURCES 93 APPENDIX: PUBLISHED SOURCES FOR TYPE DESCRIPTIONS 98 REV"I:E'VV C~S AND REPLy........................................ 99 REFERENCES CITED ••............•..•.•.....•••.•.....•..•......... 109 v I I 1 FIGURES I I 1. Physiographic provinces of Georgia 3 2. The Georgia Valley and Ridge Province 4 I 3. Physiographic divisions of the Valley and Ridge Province 5 1 4. Distribution of chert resources in the Valley and Ridge Province 7 5. River systems in the Valley and Ridge Province 8 6. Distribution of floodplain soils along major rivers in the Valley and Ridge Province 11 7. Complicated stamped motifs referred to in the text 30 8. Radiocarbon dates for Mississippian sites in the Georgia Valley and Ridge Provi nce and surrounding areas, uncorrected 37 9. -

* This Is an Excerpt from Protected Animals of Georgia Published By

Common Name: RIVER REDHORSE Scientific Name: Moxostoma carinatum (Cope) Other Commonly Used Names: none Previously Used Scientific Names: Placopharynx carinatus Family: Catostomidae Rarity Ranks: G4/S2 State Legal Status: Rare Federal Legal Status: none Description: The river redhorse is a large, heavy-bodied sucker that can attain total lengths approaching 750 mm (30 in). The margin of the dorsal fin is straight to slightly concave and the upper lobe of the dorsal fin is pointed. The lips have deep longitudinal grooves (i.e., plicae). There are 12-14 dorsal fin rays, a complete lateral line with 42-44 scales (usually), and 6-9 large molariform teeth on the lower half of the pharyngeal arch. Body coloration of adults is brassy olive and the belly is white. The dorsal and caudal fins, particularly the distal margins of these fins, are bright red in adult males and females. Juveniles have a silvery body and a blotch saddle pattern across the back; juveniles may have red caudal fins, but not as intensely red as in adults. Breeding males develop medium to large tubercles on the snout, cheeks, head, anal rays and caudal rays, and may develop smaller tubercles elsewhere. During spawning, males develop a prominent dark lateral stripe, bordered above by a tan stripe, another dark stripe and a tan or pale dorsum; there is often a dark mask on the head. These spawning colors are ephemeral and will quickly vanish, especially if the fish is disturbed. Similar Species: The undescribed sicklefin redhorse (syntopic with the river redhorse only in Brasstown Creek, Towns Co.) also has brilliant red dorsal and caudal fins, but is easily distinguished by having a sickle-shaped (vs. -

Water Use in the Tennessee Valley 2008.FH11

in the Tennessee Valley for 2005 and Projected Use in 2030 TENNESSEE VALLEY AUTHORITY Prepared by River Operations in cooperation with U.S. Geological Survey Water Use in the Tennessee Valley for 2005 and Projected Use in 2030 Charles E. Bohac Michael J. McCall November 2008 Contents List of Tables ................................................................................................................................................. iii List of Figures ................................................................................................................................................ v Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................................................... vii Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... viii Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1–1 Background ............................................................................................................................................ 1–1 Purpose and Scope ............................................................................................................................... 1–2 Hydrologic Setting .................................................................................................................................. 1–2 Data Source