Georgia's Water Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Register/Vol. 73, No. 232/Tuesday, December

73182 Federal Register / Vol. 73, No. 232 / Tuesday, December 2, 2008 / Rules and Regulations (subtitle E of the Small Business any person acting subject to the SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act of direction or control of a foreign Federal Emergency Management Agency 1996). Therefore, the reporting government or official where such (FEMA) makes the final determinations requirement of 5 U.S.C. 801 does not person is an agent of Cuba or any other listed below for the modified BFEs for apply. country that the President determines each community listed. These modified Paperwork Reduction Act (and so reports to the Congress) poses a elevations have been published in threat to the national security interest of newspapers of local circulation and The Paperwork Reduction Act (PRA) the United States for purposes of 18 ninety (90) days have elapsed since that does not apply to this rule change. See U.S.C. 951; or has been convicted of or publication. The Assistant 44 U.S.C. 3501–3521. The PRA imposes entered a plea of nolo contendere to any Administrator of the Mitigation certain protocol for the ‘‘collection of offense under 18 U.S.C. 792–799, 831, Directorate has resolved any appeals information’’ by government agencies. or 2381, or under section 11 of the resulting from this notification. The Act defines the ‘‘collection of Export Administration Act of 1979, 50 This final rule is issued in accordance information’’ as ‘‘the obtaining, causing U.S.C. app. 2410. with section 110 of the Flood Disaster to be obtained, soliciting, or requiring * * * * * Protection Act of 1973, 42 U.S.C. -

Stream-Temperature Characteristics in Georgia

STREAM-TEMPERATURE CHARACTERISTICS IN GEORGIA By T.R. Dyar and S.J. Alhadeff ______________________________________________________________________________ U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 96-4203 Prepared in cooperation with GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION DIVISION Atlanta, Georgia 1997 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Charles G. Groat, Director For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services 3039 Amwiler Road, Suite 130 Denver Federal Center Peachtree Business Center Box 25286 Atlanta, GA 30360-2824 Denver, CO 80225-0286 CONTENTS Page Abstract . 1 Introduction . 1 Purpose and scope . 2 Previous investigations. 2 Station-identification system . 3 Stream-temperature data . 3 Long-term stream-temperature characteristics. 6 Natural stream-temperature characteristics . 7 Regression analysis . 7 Harmonic mean coefficient . 7 Amplitude coefficient. 10 Phase coefficient . 13 Statewide harmonic equation . 13 Examples of estimating natural stream-temperature characteristics . 15 Panther Creek . 15 West Armuchee Creek . 15 Alcovy River . 18 Altamaha River . 18 Summary of stream-temperature characteristics by river basin . 19 Savannah River basin . 19 Ogeechee River basin. 25 Altamaha River basin. 25 Satilla-St Marys River basins. 26 Suwannee-Ochlockonee River basins . 27 Chattahoochee River basin. 27 Flint River basin. 28 Coosa River basin. 29 Tennessee River basin . 31 Selected references. 31 Tabular data . 33 Graphs showing harmonic stream-temperature curves of observed data and statewide harmonic equation for selected stations, figures 14-211 . 51 iii ILLUSTRATIONS Page Figure 1. Map showing locations of 198 periodic and 22 daily stream-temperature stations, major river basins, and physiographic provinces in Georgia. -

Fish Consumption Guidelines: Rivers & Creeks

FRESHWATER FISH CONSUMPTION GUIDELINES: RIVERS & CREEKS NO RESTRICTIONS ONE MEAL PER WEEK ONE MEAL PER MONTH DO NOT EAT NO DATA Bass, LargemouthBass, Other Bass, Shoal Bass, Spotted Bass, Striped Bass, White Bass, Bluegill Bowfin Buffalo Bullhead Carp Catfish, Blue Catfish, Channel Catfish,Flathead Catfish, White Crappie StripedMullet, Perch, Yellow Chain Pickerel, Redbreast Redhorse Redear Sucker Green Sunfish, Sunfish, Other Brown Trout, Rainbow Trout, Alapaha River Alapahoochee River Allatoona Crk. (Cobb Co.) Altamaha River Altamaha River (below US Route 25) Apalachee River Beaver Crk. (Taylor Co.) Brier Crk. (Burke Co.) Canoochee River (Hwy 192 to Ogeechee River) Chattahoochee River (Helen to Lk. Lanier) (Buford Dam to Morgan Falls Dam) (Morgan Falls Dam to Peachtree Crk.) * (Peachtree Crk. to Pea Crk.) * (Pea Crk. to West Point Lk., below Franklin) * (West Point dam to I-85) (Oliver Dam to Upatoi Crk.) Chattooga River (NE Georgia, Rabun County) Chestatee River (below Tesnatee Riv.) Conasauga River (below Stateline) Coosa River (River Mile Zero to Hwy 100, Floyd Co.) Coosa River <32" (Hwy 100 to Stateline, Floyd Co.) >32" Coosa River (Coosa, Etowah below Thompson-Weinman dam, Oostanaula) Coosawattee River (below Carters) Etowah River (Dawson Co.) Etowah River (above Lake Allatoona) Etowah River (below Lake Allatoona dam) Flint River (Spalding/Fayette Cos.) Flint River (Meriwether/Upson/Pike Cos.) Flint River (Taylor Co.) Flint River (Macon/Dooly/Worth/Lee Cos.) <16" Flint River (Dougherty/Baker Mitchell Cos.) 16–30" >30" Gum Crk. (Crisp Co.) Holly Crk. (Murray Co.) Ichawaynochaway Crk. Kinchafoonee Crk. (above Albany) Little River (above Clarks Hill Lake) Little River (above Ga. Hwy 133, Valdosta) Mill Crk. -

2009 Volume XXI, Number 1 Association, Inc

Lake Hartwell Winter, 2009 Volume XXI, Number 1 Association, Inc Letter from the President Inside this issue Submitted by Joe Brenner LHA’s Annual Fall Meeting 2 Lake Hartwell reached a record low level in October, and there’s no relief Drew Much Attention in sight. If the current drought continues, the entire conservation pool (625 LHA Represented at Historical 3 MSL) will be consumed by the end of 2009. The effects of climate change Water Conference are upon us. Though no one is sure how overall average rainfall will be affected in the southeastern U.S., all the climatologists I’ve heard from Hartwell Lake Level Projec- 4 tions (or, When will the lake have projected greater weather extremes, i.e. longer and more severe fill up again?) droughts. Ask the Corps 6 The existing Corps Drought Contingency Plan clearly cannot handle the 2008 Hartwell Lake Clean Up 7 weather patterns that we are experiencing. It is based on historical events Campaign a Success and decades old operational approaches. There must be a greater under- standing by all stakeholders within the Savannah River Basin that the reserves in the lakes must be Let’s Get Ready for Boating 8 Next Year maintained in order to protect the entire basin through severe drought situations. It must also be recognized that an appropriate drought plan will promote a “share the pain” approach throughout Proposed Nuclear Power 9 the basin. It is absurd to be holding boat races on the river in Augusta while our businesses suffer, Plant Expansion On The Savannah River our boat ramps are closed, the lake is not navigable and our docks sit on dirt. -

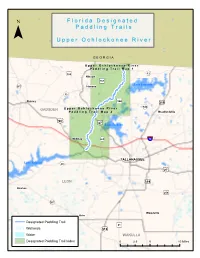

Upper Ochlockonee River Paddling Guide

F ll o r ii d a D e s ii g n a tt e d ¯ P a d d ll ii n g T r a ii ll s U p p e r O c h ll o c k o n e e R ii v e r G E O R G I A U p p e rr O c h ll o c k o n e e R ii v e rr P a d d ll ii n g T rr a ii ll M a p 1 159 «¬12 )" Hinson )"157 343 Lake Iamonia )" «¬267 Havana «¬12 344 Quincy )" ¤£319 342 GADSDEN U p p e rr O c h ll o c k o n e e R ii v e rr «¬ P a d d ll ii n g T rr a ii ll M a p 2 Bradfordville 90 ¤£ 27 ¤£ Lake Jackson Midway «¬263 ¨¦§10 1)"541 Capitola TALLAHASSEE Lake Talquin «¬20 «¬267 ¤£27 LEON ¤£319 Bloxham )"259 «¬267 Woodville Helen Designated Paddling Trail )"61 Wetlands ¤£319 Water WAKULLA Designated Paddling Trail Index 0 2.5 5 10 Miles 319 ¤£ 61 Newport Arran )" U p p e rr O c h ll o c k o n e e R ii v e rr P a d d ll ii n g T rr a ii ll M a p 1 ¯ Bell Rd d R d or n c Co o ir a C !| River Ridge «¬12 Plantation Concord Conservation Easement Access Point 1: SR 12 N: 30.6689 W: -84.3051 Havana Hiamonee à Plantation Conservation «¬12 Easement River Ridge Plantation C Conservation o n c Easement o d r R d n a R i id d r e M Kemp Rd N E D Tall Timbers Research Station S D & Land Conservancy A N O G E L Lake Iamonia I ro n B r id g e R d d Pond R ard ch Or !| Mallard Pond Access Point 2: Old Bainbridge Rd Bridge N: 30.5858 W: -84.3594 O l d B Carr Lake a i n b r i d Upper Ochlockonee River Paddling Trail g e R Canoe/Kayak Launch d !| Conservation Lands 27 0 0.5 1 2 Miles ¤£ Wetlands ¯ U p p e rr O c h ll o c k o n e e R ii v e rr P a d d ll ii n g T rr a ii ll M a p 2 )"270 RCM Farms Conservation Easement O l d B a i -

Chemical Character of Surface Waters of Georgia

SliEU' :\0..... / ........ RO O ~ l NO. ···- ··-<~ ......... U )'On no l~er need this publication write to the Geological Sur»ey in Washlndon for ali official maillne label to use In returning it UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR CHEMICAL CHARACTER OF SURFACE WATERS OF GEORGIA Prepared In cooperation wilh the DIVISION OF MINES, MINING, AND GEOLOGY OF 'l'HE GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 889- E ' UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Harold L. Ickes, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director Water-Supply Paper 889-E CHEMICAL CHARACTER OF SURFACE WATERS OF GEORGIA BY WILLIAM L. LAMAR Prepared in cooperation with the DIVISION OF MINES, MINING, AND GEOLOGY OF THE GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Contributions to the Hydrology of the United States, 19~1-!3 (Pages 317- 380) UN ITED STATES GOVEHNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1944 For sct le Ly Ll w S upcrinkntlent of Doc uments, U. S. Gover nme nt Printing Office, " ' asbingtou 25, D . C. Price 15 ce nl~ CONTENTS Page- Abstract ___________________________________________ -----_--------- 31 T Introduction __________________ c ________________________________ -- _ 317 Physiography_____________________________________________________ 318 Climate__________________________________________________________ 820 Collection and examination of samples_______________________________ 323 Stream flow __________________________ --------- ___________ c ________ . 324 Rainfall and discharge during sampling years_____________________ -

Lloyd Shoals

Southern Company Generation. 241 Ralph McGill Boulevard, NE BIN 10193 Atlanta, GA 30308-3374 404 506 7219 tel July 3, 2018 FERC Project No. 2336 Lloyd Shoals Project Notice of Intent to Relicense Lloyd Shoals Dam, Preliminary Application Document, Request for Designation under Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act and Request for Authorization to Initiate Consultation under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act Ms. Kimberly D. Bose, Secretary Federal Energy Regulatory Commission 888 First Street, N.E. Washington, D.C. 20426 Dear Ms. Bose: On behalf of Georgia Power Company, Southern Company is filing this letter to indicate our intent to relicense the Lloyd Shoals Hydroelectric Project, FERC Project No. 2336 (Lloyd Shoals Project). We will file a complete application for a new license for Lloyd Shoals Project utilizing the Integrated Licensing Process (ILP) in accordance with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s (Commission) regulations found at 18 CFR Part 5. The proposed Process, Plan and Schedule for the ILP proceeding is provided in Table 1 of the Preliminary Application Document included with this filing. We are also requesting through this filing designation as the Commission’s non-federal representative for consultation under Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act and authorization to initiate consultation under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act. There are four components to this filing: 1) Cover Letter (Public) 2) Notification of Intent (Public) 3) Preliminary Application Document (Public) 4) Preliminary Application Document – Appendix C (CEII) If you require further information, please contact me at 404.506.7219. Sincerely, Courtenay R. -

List of TMDL Implementation Plans with Tmdls Organized by Basin

Latest 305(b)/303(d) List of Streams List of Stream Reaches With TMDLs and TMDL Implementation Plans - Updated June 2011 Total Maximum Daily Loadings TMDL TMDL PLAN DELIST BASIN NAME HUC10 REACH NAME LOCATION VIOLATIONS TMDL YEAR TMDL PLAN YEAR YEAR Altamaha 0307010601 Bullard Creek ~0.25 mi u/s Altamaha Road to Altamaha River Bio(sediment) TMDL 2007 09/30/2009 Altamaha 0307010601 Cobb Creek Oconee Creek to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Cobb Creek Oconee Creek to Altamaha River FC 2012 Altamaha 0307010601 Milligan Creek Uvalda to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 2006 Altamaha 0307010601 Milligan Creek Uvalda to Altamaha River FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Oconee Creek Headwaters to Cobb Creek DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Oconee Creek Headwaters to Cobb Creek FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010602 Ten Mile Creek Little Ten Mile Creek to Altamaha River Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010602 Ten Mile Creek Little Ten Mile Creek to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010603 Beards Creek Spring Branch to Altamaha River Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010603 Five Mile Creek Headwaters to Altamaha River Bio(sediment) TMDL 2007 09/30/2009 Altamaha 0307010603 Goose Creek U/S Rd. S1922(Walton Griffis Rd.) to Little Goose Creek FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010603 Mushmelon Creek Headwaters to Delbos Bay Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010604 Altamaha River Confluence of Oconee and Ocmulgee Rivers to ITT Rayonier -

LHA News Fall 05

Lake Hartwell Fall, 2005 Volume XVII, Number 4 Association, Inc Letter from the President Inside this issue Submitted by Mike Massey 2005 Fall Informational 2 It has been a relatively beautiful summer on the lake. I hope you have all enjoyed it. Meeting The LHA Fall Meeting has been scheduled. Please take a minute to read about it and Anderson Co. Parks 3 when you have finished, mark your calendars to be sure you don’t miss out on this in- Benefit from formative annual event. Bioengineering LHA Annual Fall Meeting. Legislative Committee 4 The LHA Board of Directors is happy to announce that the Lake Hartwell Association Update annual meeting will be held on Thursday, November 10, at the Anderson Civic Center. Boating Safety 4 The meeting will start at 7:00 PM and run for approximately two hours. Request for email 4 The purpose of this meeting is to provide our members, guests and friends of the lake: Addresses • The ability to hear some very interesting and important speakers relating to Hartwell Lake and the Meet the Directors 5 Savannah River Basin • An update of the activities the LHA team has been working for the past year, Safety Alert! for PDFs 6 • The opportunity to meet your officers and members of the Board of Directors, ask questions of News From The Corps 7 them and all speakers and, Lake Level Data 7 • An opportunity to win one of the great door prizes. This year’s keynote speaker is Colonel Mark S. Held, District Commander, Savannah District, U.S. -

11-1 335-6-11-.02 Use Classifications. (1) the ALABAMA RIVER BASIN Waterbody from to Classification ALABAMA RIVER MOBILE RIVER C

335-6-11-.02 Use Classifications. (1) THE ALABAMA RIVER BASIN Waterbody From To Classification ALABAMA RIVER MOBILE RIVER Claiborne Lock and F&W Dam ALABAMA RIVER Claiborne Lock and Alabama and Gulf S/F&W (Claiborne Lake) Dam Coast Railway ALABAMA RIVER Alabama and Gulf River Mile 131 F&W (Claiborne Lake) Coast Railway ALABAMA RIVER River Mile 131 Millers Ferry Lock PWS (Claiborne Lake) and Dam ALABAMA RIVER Millers Ferry Sixmile Creek S/F&W (Dannelly Lake) Lock and Dam ALABAMA RIVER Sixmile Creek Robert F Henry Lock F&W (Dannelly Lake) and Dam ALABAMA RIVER Robert F Henry Lock Pintlala Creek S/F&W (Woodruff Lake) and Dam ALABAMA RIVER Pintlala Creek Its source F&W (Woodruff Lake) Little River ALABAMA RIVER Its source S/F&W Chitterling Creek Within Little River State Forest S/F&W (Little River Lake) Randons Creek Lovetts Creek Its source F&W Bear Creek Randons Creek Its source F&W Limestone Creek ALABAMA RIVER Its source F&W Double Bridges Limestone Creek Its source F&W Creek Hudson Branch Limestone Creek Its source F&W Big Flat Creek ALABAMA RIVER Its source S/F&W 11-1 Waterbody From To Classification Pursley Creek Claiborne Lake Its source F&W Beaver Creek ALABAMA RIVER Extent of reservoir F&W (Claiborne Lake) Beaver Creek Claiborne Lake Its source F&W Cub Creek Beaver Creek Its source F&W Turkey Creek Beaver Creek Its source F&W Rockwest Creek Claiborne Lake Its source F&W Pine Barren Creek Dannelly Lake Its source S/F&W Chilatchee Creek Dannelly Lake Its source S/F&W Bogue Chitto Creek Dannelly Lake Its source F&W Sand Creek Bogue -

Like No Place on Earth

Like no Place on Earth Heaven’s Landing, the Middle of EVERYWHERE! - Mike Ciochetti EVERYWHERE Heaven’s Landing is a residential fly-in community located in the Blue Ridge Mountains of northeast Georgia. Immediately surrounded by the pristine EVERYTHING serenity of the Chattahoochee National Forest, one could easily get the impression that Heaven’s Landing is located in the middle of nowhere. After all, virtually every photograph that you see of Heaven’s Landing shows a 5,200 The Races foot runway surrounded by colorful mountain wilderness. To the contrary, however, Heaven’s Landing is only 3.5 miles from the City of Clayton, Georgia, and very much in the middle of EVERYWHERE! Fall Sweeps A seven-minute drive from Heaven’s Landing brings you to downtown Clayton, which has the best of just about EVERYTHING! Four of the top 100 rated Where to Find Us chefs in the U.S. operate restaurants in Rabun County to the delight of gourmet foodies. Rabun County was named the “Farm to Table Capital of Georgia!” This is a testament to the great relationships the chefs have with the Circus Arts local farms, following the practices of the finest eateries, and the abundant availability of farm fresh organic meats and produce. If you don’t care to dine out, shoppers will delight in the finest supermarkets, farmer’s markets, Mark Your organic food co-op’s and old fashioned local butcher shops that you will find Calendar ANYWHERE! So Heaven’s Landing has your fine dining needs covered, what is there to do Events to work up an appetite? Once again the answer is EVERYTHING! Let’s start with Lake Burton, a renowned 2,735 acre crystal clear mountain lake where Concierge you can water ski, jet ski, fish, or just cruise on your boat and sunbathe in an atmosphere that is pure nirvana. -

Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards ( 1) Purpose. The establishment of water quality standards. (2) W ate r Quality Enhancement: (a) The purposes and intent of the State in establishing Water Quality Standards are to provide enhancement of water quality and prevention of pollution; to protect the public health or welfare in accordance with the public interest for drinking water supplies, conservation of fish, wildlife and other beneficial aquatic life, and agricultural, industrial, recreational, and other reasonable and necessary uses and to maintain and improve the biological integrity of the waters of the State. ( b) The following paragraphs describe the three tiers of the State's waters. (i) Tier 1 - Existing instream water uses and the level of water quality necessary to protect the existing uses shall be maintained and protected. (ii) Tier 2 - Where the quality of the waters exceed levels necessary to support propagation of fish, shellfish, and wildlife and recreation in and on the water, that quality shall be maintained and protected unless the division finds, after full satisfaction of the intergovernmental coordination and public participation provisions of the division's continuing planning process, that allowing lower water quality is necessary to accommodate important economic or social development in the area in which the waters are located.