Outline for Renewed Research Regarding My Master Thesis on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hier Steht Später Die Headline

S OUTH AFRICA : COUNTRY PROFILE Konrad Adenauer Foundation Last Update: April 2019 ww.kas.de/Südafrika COUNTRY OFFICE SOUTH AFRICA Country Profile South Africa Konrad Adenauer Foundation Contents 1 General Information: Republic of South Africa ......................................................................................... 2 2 History ............................................................................................................................................... 3 3 The Political System of South Africa ....................................................................................................... 4 3.1 Executive Power .............................................................................................................................. 4 3.1.1 National Level ................................................................................................................................. 4 3.1.2 Provincial Level ............................................................................................................................... 5 3.2 Judicial Power ................................................................................................................................. 5 3.3 Legislative Power ............................................................................................................................. 6 3.3.1 National Level ................................................................................................................................. 6 4 Economy ......................................................................................................................................... -

Why Labour Can't Get ANC to Work

Why labour can ’t get ANC to work - Sunday Independent | IOL.co.za Page 1 of 2 IOL Newsletters Sign up now Sponsored Links: IOL Travel Personal Finance IOL Lifestyle Motoring SciTech Tonight All Channels 6 Search Advanced Search Home News Life Analysis International SA Time: 19 July 2011 11:00:48 AM Why labour can ’t get ANC to work 5.1 Surround Speakers Explosive 5.1 surround sound for PC July 11 2011 at 09:48am Creative Speakers for under R100 By Mcebisi Ndletyana WantItCheap.co.za Cheap Car Insurance It’s true. History does repeat itself. Perhaps with even Submit Your Details & We Call You With more frequency in our case than is usual. Yet, the Cheap Car Insurance Quotes! ANC-led tripartite alliance partners greet every www.get -insured.co.za recurrence with an even louder expression of shock Save on Car Insurance and deep disappointment at unmet expectations. Get Up To 9 Insurance Quotes. Save Money Then, they recommit, professing even more sincerity Guaranteed! and vigour to realise their objectives. The structure of www.youinsure.co.za/ the alliance, however, remains as before. But, they somehow manage to bring themselves to believing that the outcome will be different this time around. It’s a dance that the tripartite alliance has come to master. The outcome of Cosatu’s recent gathering was déjà Sunday Independent vu. Zwelinzima Vavi’s Secretariat’s Report decried the moribund state of the South African Communist SundayIndy Party. Rather than assume the vanguard role that history has accorded it vis-à-vis the working people, the party, Vavi writes, is largely inactive awakening only when deployments are discussed. -

Jacob Zuma: the Man of the Moment Or the Man for the Moment? Alex Michael & James Montagu

Research & Assessment Branch African Series Jacob Zuma: The Man of the Moment or the Man for the Moment? Alex Michael & James Montagu 09/08 Jacob Zuma: The Man of the Moment or the Man for the Moment? Alex Michael & James Montagu Key Findings • Zuma is a pragmatist, forging alliances based on necessity rather than ideology. His enlarged but inclusive cabinet, rewards key allies with significant positions, giving minor roles to the leftist SACP and COSATU. • Long-term ANC allies now hold key Justice, Police and State Security ministerial positions, reducing the likelihood of legal charges against him resurfacing. • The blurring of party and state to the detriment of public institutions, which began under Mbeki, looks set to continue under Zuma. • Zuma realises that South Africa relies too heavily on foreign investment, but no real change in economic policy could well alienate much of his populist support base and be decisive in the longer term. 09/08 Jacob Zuma: The Man of the Moment or the Man for the Moment? Alex Michael & James Montagu INTRODUCTION Jacob Zuma, the new President of the Republic of South Africa and the African National Congress (ANC), is a man who divides opinion. He has been described by different groups as the next Mandela and the next Mugabe. He is a former goatherd from what is now called KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) with no formal education and a long career in the ANC, which included a 10 year spell at Robben Island and 14 years of exile in Mozambique, Swaziland and Zambia. Like most ANC leaders, his record is not a clean one and his role in identifying and eliminating government spies within the ranks of the ANC is well documented. -

The Referendum in FW De Klerk's War of Manoeuvre

The referendum in F.W. de Klerk’s war of manoeuvre: An historical institutionalist account of the 1992 referendum. Gary Sussman. London School of Economics and Political Science. Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government and International History, 2003 UMI Number: U615725 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615725 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 T h e s e s . F 35 SS . Library British Library of Political and Economic Science Abstract: This study presents an original effort to explain referendum use through political science institutionalism and contributes to both the comparative referendum and institutionalist literatures, and to the political history of South Africa. Its source materials are numerous archival collections, newspapers and over 40 personal interviews. This study addresses two questions relating to F.W. de Klerk's use of the referendum mechanism in 1992. The first is why he used the mechanism, highlighting its role in the context of the early stages of his quest for a managed transition. -

EB145 Opt.Pdf

E EPISCOPAL CHURCHPEOPLE for a FREE SOUTHERN AFRICA 339 Lafayette Street, New York, N.Y. 10012·2725 C (212) 4n-0066 FAX: (212) 979-1013 S A #145 21 february 1994 _SU_N_D_AY-.::..:20--:FEB:.=:..:;R..:..:U..:..:AR:..:.Y:.....:..:.1994::...::.-_---.". ----'-__THE OBSERVER_ Ten weeks before South Africa's elections, a race war looks increasingly likely, reports Phillip van Niekerk in Johannesburg TOKYO SEXWALE, the Afri In S'tanderton, in the Eastern candidate for the premiership of At the meeting in the Pretoria Many leading Inkatha mem can National Congress candidate Transvaal, the white town coun Natal. There is little doubt that showgrounds three weeks ago, bers have publicly and privately for the office of premier in the cillast Wednesday declared itself Natal will fall to the ANC on 27 when General Constand Viljoen, expressed their dissatisfaction at Pretoria-Witwatersrand-Veree part of an independent Boer April, which explains Buthelezi's head ofthe Afrikaner Volksfront, Inkatha's refusal to participate in niging province, returned shaken state, almost provoking a racial determination to wriggle out of was shouted down while advo the election, and could break from a tour of the civil war in conflagration which, for all the having to fight the dection.~ cating the route to a volkstaat not away. Angola last Thursday. 'I have violence of recent years, the At the very least, last week's very different to that announced But the real prize in Natal is seen the furure according to the country not yet experienced. concessions removed any trace of by Mandela last week, the im Goodwill Zwelithini, the Zulu right wing,' he said, vividly de The council's declaration pro a legitimate gripe against the new pression was created that the king and Buthelezi's nephew. -

EASTERN CAPE NARL 2014 (Approved by the Federal Executive)

EASTERN CAPE NARL 2014 (Approved by the Federal Executive) Rank Name 1 Andrew (Andrew Whitfield) 2 Nosimo (Nosimo Balindlela) 3 Kevin (Kevin Mileham) 4 Terri Stander 5 Annette Steyn 6 Annette (Annette Lovemore) 7 Confidential Candidate 8 Yusuf (Yusuf Cassim) 9 Malcolm (Malcolm Figg) 10 Elza (Elizabeth van Lingen) 11 Gustav (Gustav Rautenbach) 12 Ntombenhle (Rulumeni Ntombenhle) 13 Petrus (Petrus Johannes de WET) 14 Bobby Cekisani 15 Advocate Tlali ( Phoka Tlali) EASTERN CAPE PLEG 2014 (Approved by the Federal Executive) Rank Name 1 Athol (Roland Trollip) 2 Vesh (Veliswa Mvenya) 3 Bobby (Robert Stevenson) 4 Edmund (Peter Edmund Van Vuuren) 5 Vicky (Vicky Knoetze) 6 Ross (Ross Purdon) 7 Lionel (Lionel Lindoor) 8 Kobus (Jacobus Petrus Johhanes Botha) 9 Celeste (Celeste Barker) 10 Dorah (Dorah Nokonwaba Matikinca) 11 Karen (Karen Smith) 12 Dacre (Dacre Haddon) 13 John (John Cupido) 14 Goniwe (Thabisa Goniwe Mafanya) 15 Rene (Rene Oosthuizen) 16 Marshall (Marshall Von Buchenroder) 17 Renaldo (Renaldo Gouws) 18 Bev (Beverley-Anne Wood) 19 Danny (Daniel Benson) 20 Zuko (Prince-Phillip Zuko Mandile) 21 Penny (Penelope Phillipa Naidoo) FREE STATE NARL 2014 (as approved by the Federal Executive) Rank Name 1 Patricia (Semakaleng Patricia Kopane) 2 Annelie Lotriet 3 Werner (Werner Horn) 4 David (David Christie Ross) 5 Nomsa (Nomsa Innocencia Tarabella Marchesi) 6 George (George Michalakis) 7 Thobeka (Veronica Ndlebe-September) 8 Darryl (Darryl Worth) 9 Hardie (Benhardus Jacobus Viviers) 10 Sandra (Sandra Botha) 11 CJ (Christian Steyl) 12 Johan (Johannes -

African National Congress NATIONAL to NATIONAL LIST 1. ZUMA Jacob

African National Congress NATIONAL TO NATIONAL LIST 1. ZUMA Jacob Gedleyihlekisa 2. MOTLANTHE Kgalema Petrus 3. MBETE Baleka 4. MANUEL Trevor Andrew 5. MANDELA Nomzamo Winfred 6. DLAMINI-ZUMA Nkosazana 7. RADEBE Jeffery Thamsanqa 8. SISULU Lindiwe Noceba 9. NZIMANDE Bonginkosi Emmanuel 10. PANDOR Grace Naledi Mandisa 11. MBALULA Fikile April 12. NQAKULA Nosiviwe Noluthando 13. SKWEYIYA Zola Sidney Themba 14. ROUTLEDGE Nozizwe Charlotte 15. MTHETHWA Nkosinathi 16. DLAMINI Bathabile Olive 17. JORDAN Zweledinga Pallo 18. MOTSHEKGA Matsie Angelina 19. GIGABA Knowledge Malusi Nkanyezi 20. HOGAN Barbara Anne 21. SHICEKA Sicelo 22. MFEKETO Nomaindiya Cathleen 23. MAKHENKESI Makhenkesi Arnold 24. TSHABALALA- MSIMANG Mantombazana Edmie 25. RAMATHLODI Ngoako Abel 26. MABUDAFHASI Thizwilondi Rejoyce 27. GODOGWANA Enoch 28. HENDRICKS Lindiwe 29. CHARLES Nqakula 30. SHABANGU Susan 31. SEXWALE Tokyo Mosima Gabriel 32. XINGWANA Lulama Marytheresa 33. NYANDA Siphiwe 34. SONJICA Buyelwa Patience 35. NDEBELE Joel Sibusiso 36. YENGENI Lumka Elizabeth 37. CRONIN Jeremy Patrick 38. NKOANA- MASHABANE Maite Emily 39. SISULU Max Vuyisile 40. VAN DER MERWE Susan Comber 41. HOLOMISA Sango Patekile 42. PETERS Elizabeth Dipuo 43. MOTSHEKGA Mathole Serofo 44. ZULU Lindiwe Daphne 45. CHABANE Ohm Collins 46. SIBIYA Noluthando Agatha 47. HANEKOM Derek Andre` 48. BOGOPANE-ZULU Hendrietta Ipeleng 49. MPAHLWA Mandisi Bongani Mabuto 50. TOBIAS Thandi Vivian 51. MOTSOALEDI Pakishe Aaron 52. MOLEWA Bomo Edana Edith 53. PHAAHLA Matume Joseph 54. PULE Dina Deliwe 55. MDLADLANA Membathisi Mphumzi Shepherd 56. DLULANE Beauty Nomvuzo 57. MANAMELA Kgwaridi Buti 58. MOLOI-MOROPA Joyce Clementine 59. EBRAHIM Ebrahim Ismail 60. MAHLANGU-NKABINDE Gwendoline Lindiwe 61. NJIKELANA Sisa James 62. HAJAIJ Fatima 63. -

Open Letter to ANC Secretary General Comrade Gwede Mantashe

Open letter to ANC Secretary General Comrade Gwede Mantashe Dear Comrade Secretary General I have decided to take the unusual step to write you an open letter because the unusual situation that has now arisen in the ANC and the tripartite alliance requires extraordinary steps. I write to place on record the concerns I see as gnawing away at the ANC, with the hope that the leadership might wake up to the dangers our movement faces. When I joined the ANC, I was attracted by its policies, political culture, values, history and its commitment to the interests of our people - black and white. I am still as fervently committed to this cause as when I first joined the organisation. However, for some time now, I have lived with the growing sense that our leadership has veered the organisation away from the established policy priorities and customary democratic norms of the ANC. (i) For instance, those who express views that are contrary to popular opinion in meetings and conferences of the organisation are later hounded out and purged from organisation and state structures. This is contrary to the ANC's democratic culture. (ii) Sectoral and individual interests other than those flowing from the people's interests expressed in the Freedom Charter are elevated to levels of national priority. Thus we are expected to show up at criminal court cases or carry shoulder high individuals convicted of crimes unrelated to the demands in the Freedom Charter. (iii) Instead of instilling respect for institutions of democracy, our leaders issue threats that if judicial proceedings do not result in outcomes they prefer, the country will be brought to a standstill. -

Gender Audit of the May 2019 South African Elections

BEYOND NUMBERS: GENDER AUDIT OF THE MAY 2019 SOUTH AFRICAN ELECTIONS Photo: Colleen Lowe Morna By Kubi Rama and Colleen Lowe Morna 0 697 0 6907 1 7 2 9 4852 9 4825 649 7 3 7 3 93 85 485 68 485 768485 0 21 0 210 168 01697 016907 127 2 9 4852 9 4825 649 7 3 7 3 93 85 485 68 485 768485 0 21 0 210 168 01697 016907 127 2 9 4852 9 4825 649 7 3 7 3 93 85 485 68 485 768485 0 21 0 210 168 01697 016907 127 2 9 4852 9 4825 649 7 3 7 3 93 85 485 68 485 768485 6 0 21 0 210 18 01697 016907 127 2 9 4852 9 4825 649 7 3 7 3 93 85 485 6 485 76485 0 0 0 6 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 QUOTAS AND PARTY LISTS 4 WOMEN'S PERFORMANCE IN THE ELECTIONS 5 • The National Council of Provinces or upper house 6 • Cabinet 7 • Provincial legislatures 8 • Speakers at national and provincial level 9 WOMEN AS VOTERS 9 • Giving young people a reason to vote 10 BEYOND NUMBERS: GENDER ANALYSIS OF POLITICAL PARTY MANIFESTOS 11 VOICE AND CHOICE? WOMEN EVEN LESS VISIBLE IN THE MEDIA 13 CONCLUSIONS 16 RECOMMENDATIONS 17 List of figures One: Proportion of women in the house of assembly from 1994 to 2019 5 Two: Breakdown of the NCOP by sex 6 Three: Proportion of ministers and deputy ministers by sex 7 Four: Proportion of women and men registered voters in South Africa as at May 2019 9 Five: Topics that received less than 0.2% coverage 14 List of tables One: Women in politics in South Africa, 2004 - 2019 3 Two: Quotas and positioning of women in the party lists 2019 4 Three: Gender audit of provincial legislatures 8 Four: Sex disaggregated data on South African voters by age -

At the Intersection of Neoliberal Development, Scarce Resources, and Human Rights: Enforcing the Right to Water in South Africa Elizabeth A

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College International Studies Honors Projects International Studies Department Spring 5-3-2010 At the intersection of neoliberal development, scarce resources, and human rights: Enforcing the right to water in South Africa Elizabeth A. Larson Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/intlstudies_honors Part of the African Studies Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, International Law Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, Political Economy Commons, and the Water Law Commons Recommended Citation Larson, Elizabeth A., "At the intersection of neoliberal development, scarce resources, and human rights: Enforcing the right to water in South Africa" (2010). International Studies Honors Projects. Paper 10. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/intlstudies_honors/10 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the International Studies Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Studies Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. At the intersection of neoliberal development, scarce resources, and human rights: Enforcing the right to water in South Africa Elizabeth A. Larson Honors Thesis Advisor: Professor James von Geldern Department: International Studies Abstract The competing ideals of international human rights and global economic neoliberalism come into conflict when developing countries try to enforce socio- economic rights. This paper explores the intersection of economic globalization and the enforcement of 2 nd generation human rights. The focus of this exploration is the right to water in South Africa, specifically the recent Constitutional Court case Mazibuko v City of Johannesburg . -

The New Cabinet

Response May 30th 2019 The New Cabinet President Cyril Ramaphosa’s cabinet contains quite a number of bold and unexpected appointments, and he has certainly shifted the balance in favour of female and younger politicians. At the same time, a large number of mediocre ministers have survived, or been moved sideways, while some of the most experienced ones have been discarded. It is significant that the head of the ANC Women’s League, Bathabile Dlamini, has been left out – the fact that her powerful position within the party was not enough to keep her in cabinet may be indicative of the President’s growing strength. She joins another Zuma loyalist, Nomvula Mokonyane, on the sidelines, but other strong Zuma supporters have survived. Lindiwe Zulu, for example, achieved nothing of note in five years as Minister of Small Business Development, but has now been given the crucial portfolio of social development; and Nathi Mthethwa has been given sports in addition to arts and culture. The inclusion of Patricia de Lille was unforeseen, and it will be fascinating to see how, as one of the more outspokenly critical opposition figures, she works within the framework of shared cabinet responsibility. Ms de Lille has shown herself willing to change parties on a regular basis and this appointment may presage her absorbtion into the ANC. On the other hand, it may also signal an intention to experiment with a more inclusive model of government, reminiscent of the ‘government of national unity’ that Nelson Mandela favoured. During her time as Mayor of Cape Town Ms de Lille emphasised issues of spatial planning and land-use, and this may have prompted Mr Ramaphosa to entrust her with management of the Department of Public Works’ massive land and property holdings. -

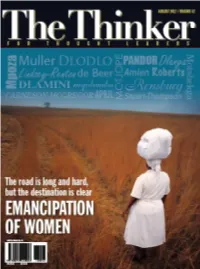

The Thinker Congratulates Dr Roots Everywhere

CONTENTS In This Issue 2 Letter from the Editor 6 Contributors to this Edition The Longest Revolution 10 Angie Motshekga Sex for sale: The State as Pimp – Decriminalising Prostitution 14 Zukiswa Mqolomba The Century of the Woman 18 Amanda Mbali Dlamini Celebrating Umkhonto we Sizwe On the Cover: 22 Ayanda Dlodlo The journey is long, but Why forsake Muslim women? there is no turning back... 26 Waheeda Amien © GreatStock / Masterfile The power of thinking women: Transformative action for a kinder 30 world Marthe Muller Young African Women who envision the African future 36 Siki Dlanga Entrepreneurship and innovation to address job creation 30 40 South African Breweries Promoting 21st century South African women from an economic 42 perspective Yazini April Investing in astronomy as a priority platform for research and 46 innovation Naledi Pandor Why is equality between women and men so important? 48 Lynn Carneson McGregor 40 Women in Engineering: What holds us back? 52 Mamosa Motjope South Africa’s women: The Untold Story 56 Jennifer Lindsey-Renton Making rights real for women: Changing conversations about 58 empowerment Ronel Rensburg and Estelle de Beer Adopt-a-River 46 62 Department of Water Affairs Community Health Workers: Changing roles, shifting thinking 64 Melanie Roberts and Nicola Stuart-Thompson South African Foreign Policy: A practitioner’s perspective 68 Petunia Mpoza Creative Lens 70 Poetry by Bridget Pitt Readers' Forum © SAWID, SAB, Department of 72 Woman of the 21st Century by Nozibele Qutu Science and Technology Volume 42 / 2012 1 LETTER FROM THE MaNagiNg EDiTOR am writing the editorial this month looks forward, with a deeply inspiring because we decided that this belief that future generations of black I issue would be written entirely South African women will continue to by women.