Das Rheingold Libretto and Music by Richard Wagner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inside the Ring: Essays on Wagner's Opera Cycle

Inside the Ring: Essays on Wagner’s Opera Cycle John Louis DiGaetani Professor Department of English and Freshman Composition James Morris as Wotan in Wagner’s Die Walküre. Photo: Jennifer Carle/The Metropolitan Opera hirty years ago I edited a book in the 1970s, the problem was finding a admirer of Hitler and she turned the titled Penetrating Wagner’s Ring: performance of the Ring, but now the summer festival into a Nazi showplace An Anthology. Today, I find problem is finding a ticket. Often these in the 1930s and until 1944 when the myself editing a book titled Ring cycles — the four operas done festival was closed. But her sons, Inside the Ring: Essays on within a week, as Wagner wanted — are Wieland and Wolfgang, managed to T Wagner’s Opera Cycle — to be sold out a year in advance of the begin- reopen the festival in 1951; there, published by McFarland Press in spring ning of the performances, so there is Wieland and Wolfgang’s revolutionary 2006. Is the Ring still an appropriate clearly an increasing demand for tickets new approaches to staging the Ring and subject for today’s audiences? Absolutely. as more and more people become fasci- the other Wagner operas helped to In fact, more than ever. The four operas nated by the Ring cycle. revive audience interest and see that comprise the Ring cycle — Das Wagnerian opera in a new visual style Rheingold, Die Walküre, Siegfried, and Political Complications and without its previous political associ- Götterdämmerung — have become more ations. Wieland and Wolfgang Wagner and more popular since the 1970s. -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

WAGNER and the VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’S Works Is More Closely Linked with Old Norse, and More Especially Old Icelandic, Culture

WAGNER AND THE VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’s works is more closely linked with Old Norse, and more especially Old Icelandic, culture. It would be carrying coals to Newcastle if I tried to go further into the significance of the incom- parable eddic poems. I will just mention that on my first visit to Iceland I was allowed to gaze on the actual manuscript, even to leaf through it . It is worth noting that Richard Wagner possessed in his library the same Icelandic–German dictionary that is still used today. His copy bears clear signs of use. This also bears witness to his search for the meaning and essence of the genuinely mythical, its very foundation. Wolfgang Wagner Introduction to the program of the production of the Ring in Reykjavik, 1994 Selma Gu›mundsdóttir, president of Richard-Wagner-Félagi› á Íslandi, pre- senting Wolfgang Wagner with a facsimile edition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda on his eightieth birthday in Bayreuth, August 1999. Árni Björnsson Wagner and the Volsungs Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen Viking Society for Northern Research University College London 2003 © Árni Björnsson ISBN 978 0 903521 55 0 The cover illustration is of the eruption of Krafla, January 1981 (Photograph: Ómar Ragnarsson), and Wagner in 1871 (after an oil painting by Franz von Lenbach; cf. p. 51). Cover design by Augl‡singastofa Skaparans, Reykjavík. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 7 BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGNER ............................ 17 CHRONOLOGY ............................................................................... 64 DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS ..68 ICELANDIC STUDIES IN GERMANY ......................................... -

Wagner in Comix and 'Toons

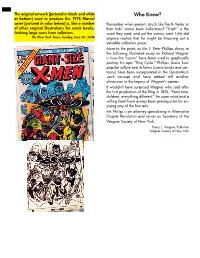

- The original artwork [pictured in black and white Who Knew? at bottom] used to produce the 1975 Marvel cover [pictured in color below] is, like a number Remember when parents struck like Darth Vader at of other original illustrations for comic books, their kids’ comic book collections? “Trash” is the fetching large sums from collectors. word they used, and out the comics went. Little did The New York Times, Sunday, June 30, 2008 anyone realize that he might be throwing out a valuable collectors piece. More to the point, as Mr. F. Peter Phillips shows in the following illustrated essay on Richard Wagner is how the “comix” have been used to graphically portray his epic “Rng Cycle.” Phillips shows how popular culture and its forms (comic books and car- toons) have been incorporated in the Gesamtkust- werk concept and have added still another dimension to the legacy of Wagner’s operas. It wouldn’t have surprised Wagner who said after the first production of the Ring in 1876, “Next time, children, everything different.” An open mind and a willing heart have always been prerequisites for en- joying any of the fine arts. Mr. Phllips is an attorney specializing in Alternative Dispute Resolution and serves as Secretary of the Wagner Society of New York. Harry L. Wagner, Publisher Wagner Society of New York Wagner in Comix and ‘Toons By F. Peter Phillips Recent publications have revealed an aspect of Wagner-inspired literature that has been grossly overlooked—Wagner in graphic art (i.e., comics) and in animated cartoons. The Ring has been ren- dered into comics of substantial integrity at least three times in the past two decades, and a recent scholarly study of music used in animated cartoons has noted uses of Wagner’s music that suggest that Wagner’s influence may even more profoundly im- bued in our culture than we might have thought. -

Wagner: Das Rheingold

as Rhe ai Pu W i D ol til a n ik m in g n aR , , Y ge iin s n g e eR Rg s t e P l i k e R a a e Y P o V P V h o é a R l n n C e R h D R ü e s g t a R m a e R 2 Das RheingolD Mariinsky Richard WAGNER / Рихард ВагнеР 3 iii. Nehmt euch in acht! / Beware! p19 7’41” (1813–1883) 4 iv. Vergeh, frevelender gauch! – Was sagt der? / enough, blasphemous fool! – What did he say? p21 4’48” 5 v. Ohe! Ohe! Ha-ha-ha! Schreckliche Schlange / Oh! Oh! Ha ha ha! terrible serpent p21 6’00” DAs RhEingolD Vierte szene – scene Four (ThE Rhine GolD / Золото Рейна) 6 i. Da, Vetter, sitze du fest! / Sit tight there, kinsman! p22 4’45” 7 ii. Gezahlt hab’ ich; nun last mich zieh’n / I have paid: now let me depart p23 5’53” GoDs / Боги 8 iii. Bin ich nun frei? Wirklich frei? / am I free now? truly free? p24 3’45” Wotan / Вотан..........................................................................................................................................................................René PaPe / Рене ПАПЕ 9 iv. Fasolt und Fafner nahen von fern / From afar Fasolt and Fafner are approaching p24 5’06” Donner / Доннер.............................................................................................................................................alexei MaRKOV / Алексей Марков 10 v. Gepflanzt sind die Pfähle / These poles we’ve planted p25 6’10” Froh / Фро................................................................................................................................................Sergei SeMISHKUR / Сергей СемишкуР loge / логе..................................................................................................................................................Stephan RügaMeR / Стефан РюгАМЕР 11 vi. Weiche, Wotan, weiche! / Yield, Wotan, yield! p26 5’39” Fricka / Фрикка............................................................................................................................ekaterina gUBaNOVa / Екатерина губАновА 12 vii. -

Ebook Download Wagners Ring Turning the Sky Around

WAGNERS RING TURNING THE SKY AROUND - AN INTRODUCTION TO THE RING OF THE NIBELUNG 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK M Owen Lee | 9780879101862 | | | | | Wagners Ring Turning the Sky Around - An Introduction to the Ring of the Nibelung 1st edition PDF Book It is even possible for the orchestra to convey ideas that are hidden from the characters themselves—an idea that later found its way into film scores. Unfamiliarity with Wagner constitutes an ignorance of, well, Wagnerian proportions. Some of my friends have seen far more than these. This section does not cite any sources. Digital watches chime the hour in half-diminished seventh chords. The daughters of the Rhine come up and pull Hagen into the depth of the Rhine. The plot synopses were helpful, but some of the deep psychological analysis was a bit boring. Next he encounters Wotan his grandfather , quarrels with him and cuts Wotan's staff of power in half. The next possessor of the ring, the giant Fafner, consumed with greed and lust for power, kills his brother, Fasolt, taking the spoils to the deep forest while the gods enter Valhalla to some of the most glorious and ironically triumphant music imaginable. Has underlining on pages. John shares his recipe for Nectar of the Gods. April Learn how and when to remove this template message. It's actually OK because that's what Wotan decreed for her anyway: First one up there shall have you. See Article History. Politics and music often go together. It left me at a whole new level of self-awareness, and has for all the years that have followed given me pleasures and insights that have enriched my life. -

Notes on Wagner's Ring Cycle

THE RING CYCLE BACKGROUND FOR NC OPERA By Margie Satinsky President, Triangle Wagner Society April 9, 2019 Wagner’s famous Ring Cycle includes four operas: Das Rheingold, Die Walkure, Siegfried, and Gotterdammerung. What’s so special about the Ring Cycle? Here’s what William Berger, author of Wagner without Fear, says: …the Ring is probably the longest chunk of music and/or drama ever put before an audience. It is certainly one of the best. There is nothing remotely like it. The Ring is a German Romantic view of Norse and Teutonic myth influenced by both Greek tragedy and a Buddhist sense of destiny told with a sociopolitical deconstruction of contemporary society, a psychological study of motivation and action, and a blueprint for a new approach to music and theater.” One of the most fascinating characteristics of the Ring is the number of meanings attributed to it. It has been seen as a justification for governments and a condemnation of them. It speaks to traditionalists and forward-thinkers. It is distinctly German and profoundly pan-national. It provides a lifetime of study for musicologists and thrilling entertainment. It is an adventure for all who approach it. SPECIAL FEATURES OF THE RING CYCLE Wagner was extremely critical of the music of his day. Unlike other composers, he not only wrote the music and the libretto, but also dictated the details of each production. The German word for total work of art, Gesamtkunstwerk, means the synthesis of the poetic, visual, musical, and dramatic arts with music subsidiary to drama. As a composer, Wagner was very interested in themes, and he uses them in The Ring Cycle in different ways. -

2021 WFMT Opera Series Broadcast Schedule & Cast Information —Spring/Summer 2021

2021 WFMT Opera Series Broadcast Schedule & Cast Information —Spring/Summer 2021 Please Note: due to production considerations, duration for each production is subject to change. Please consult associated cue sheet for final cast list, timings, and more details. Please contact [email protected] for more information. PROGRAM #: OS 21-01 RELEASE: June 12, 2021 OPERA: Handel Double-Bill: Acis and Galatea & Apollo e Dafne COMPOSER: George Frideric Handel LIBRETTO: John Gay (Acis and Galatea) G.F. Handel (Apollo e Dafne) PRESENTING COMPANY: Haymarket Opera Company CAST: Acis and Galatea Acis Michael St. Peter Galatea Kimberly Jones Polyphemus David Govertsen Damon Kaitlin Foley Chorus Kaitlin Foley, Mallory Harding, Ryan Townsend Strand, Jianghai Ho, Dorian McCall CAST: Apollo e Dafne Apollo Ryan de Ryke Dafne Erica Schuller ENSEMBLE: Haymarket Ensemble CONDUCTOR: Craig Trompeter CREATIVE DIRECTOR: Chase Hopkins FILM DIRECTOR: Garry Grasinski LIGHTING DESIGNER: Lindsey Lyddan AUDIO ENGINEER: Mary Mazurek COVID COMPLIANCE OFFICER: Kait Samuels ORIGINAL ART: Zuleyka V. Benitez Approx. Length: 2 hours, 48 minutes PROGRAM #: OS 21-02 RELEASE: June 19, 2021 OPERA: Tosca (in Italian) COMPOSER: Giacomo Puccini LIBRETTO: Luigi Illica & Giuseppe Giacosa VENUE: Royal Opera House PRESENTING COMPANY: Royal Opera CAST: Tosca Angela Gheorghiu Cavaradossi Jonas Kaufmann Scarpia Sir Bryn Terfel Spoletta Hubert Francis Angelotti Lukas Jakobski Sacristan Jeremy White Sciarrone Zheng Zhou Shepherd Boy William Payne ENSEMBLE: Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, -

Metropolitan Opera 2018-19 Review: Das Rheingold 10.03.2019, 17�43

Metropolitan Opera 2018-19 Review: Das Rheingold 10.03.2019, 1743 March 10, 2019 Contact Us Advertise Join the Team I'm looking for.... ! Login ! " # The high and low notes from around the international opera stage " Home / Metropolitan Opera 2018-19 Review: Das Rheingold In Review Stage Reviews ! # Metropolitan Opera 2018-19 Review: Das + Rheingold % Tomasz Konieczny, Nor- & bert Ernst Have Unfor- gettable Debuts By David Salazar # 4 hours ago $ 0 Com- ments Opera For Wagner’s “Der Ring Des Nibelungen” made its Beginners long-awaited comeback to the Met Opera on Saturday afternoon with a performance of “Das Rheingold.” http://operawire.com/metropolitan-opera-2018-19-review-das-r…wAR2SypogJh_NmloySPj5cavLe0I3EOdDks6XpcEM6b0uMNjyu7oCjE1d_3s Strona 1 z 14 Metropolitan Opera 2018-19 Review: Das Rheingold 10.03.2019, 1743 The Wagner epic is always a major draw for audiences and the house was packed for the Opera For Beginners matinee performance which marked the re- turn of the famed “machine” production by Robert LePage as well as a number of debuts in the cast. In fact, it is safe to say that the debutants were the ultimate scene stealers of Librettist Profile: The Tumultuous the performance. Life of Lorenzo Da Ponte, The… Dominant Debutants Any comment on this performance much start with Tomasz Konieczny, who has been making waves in Europe for years. While he has done Wotan, he was cast here as the “vil- lainous” Alberich. The truth is that Konieczny conjured up one of the greatest Met perfor- mances of the season, creating a rich portray- al of a tragic Ngure who is scorned and reject- ed by those who feel themselves superior to him. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Gustav Mahler, Alfred Roller, and the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk: Tristan and Affinities Between the Arts at the Vienna Court Opera Stephen Carlton Thursby Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GUSTAV MAHLER, ALFRED ROLLER, AND THE WAGNERIAN GESAMTKUNSTWERK: TRISTAN AND AFFINITIES BETWEEN THE ARTS AT THE VIENNA COURT OPERA By STEPHEN CARLTON THURSBY A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephen Carlton Thursby defended on April 3, 2009. _______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation _______________________________ Lauren Weingarden Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Douglass Seaton, Chair, Musicology ___________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my wonderful wife Joanna, for whose patience and love I am eternally grateful. In memory of my grandfather, James C. Thursby (1926-2008). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the generous assistance and support of numerous people. My thanks go to the staff of the Austrian Theater Museum and Austrian National Library-Music Division, especially to Dr. Vana Greisenegger, curator of the visual materials in the Alfred Roller Archive of the Austrian Theater Museum. I would also like to thank the musicology faculty of the Florida State University College of Music for awarding me the Curtis Mayes Scholar Award, which funded my dissertation research in Vienna over two consecutive summers (2007- 2008). -

Apocalypticism in Wagner's Ring by Woodrow Steinken BA, New York

Title Page Everything That Is, Ends: Apocalypticism in Wagner’s Ring by Woodrow Steinken BA, New York University, 2015 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 2018 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2021 Committee Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Woodrow Steinken It was defended on March 23, 2021 and approved by James Cassaro, Professor, Music Adriana Helbig, Associate Professor, Music David Levin, Professor, Germanic Studies Dan Wang, Assistant Professor, Music Dissertation Director: Olivia Bloechl Professor, Music ii Copyright © by Woodrow Steinken 2021 iii Abstract Everything That Is, Ends: Apocalypticism in Wagner’s Ring Woodrow Steinken, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2021 This dissertation traces the history of apocalypticism, broadly conceived, and its realization on the operatic stage by Richard Wagner and those who have adapted his works since the late nineteenth century. I argue that Wagner’s cycle of four operas, Der Ring des Nibelungen (1876), presents colloquial conceptions of time, space, and nature via supernatural, divine characters who often frame the world in terms of non-rational metaphysics. Primary among these minor roles is Erda, the personification of the primordial earth. Erda’s character prophesies the end of the world in Das Rheingold, a prophecy undone later in Siegfried by Erda’s primary interlocutor and chief of the gods, Wotan. I argue that Erda’s role changes in various stage productions of the Ring, and these changes bespeak a shifting attachment between humanity, the earth, and its imagined apocalyptic demise. -

Gesamttext Als Download (PDF)

DER RING DES NIBELUNGEN Bayreuth 1976-1980 Eine Betrachtung der Inszenierung von Patrice Chéreau und eine Annäherung an das Gesamtkunstwerk Magisterarbeit in der Philosophischen Fakultät II (Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaften) der Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg vorgelegt von Jochen Kienbaum aus Gummersbach Der Ring 1976 - 1980 Inhalt Vorbemerkung Im Folgenden wird eine Zitiertechnik verwendet, die dem Leser eine schnelle Orientierung ohne Nachschlagen ermöglichen soll und die dabei gleichzeitig eine unnötige Belastung des Fußnotenapparates sowie über- flüssige Doppelnachweise vermeidet. Sie folgt dem heute gebräuchlichen Kennziffernsystem. Die genauen bibliographischen Daten eines Zitates können dabei über Kennziffern ermittelt werden, die in Klammern hinter das Zitat gesetzt werden. Dabei steht die erste Ziffer für das im Literaturverzeichnis angeführte Werk und die zweite Ziffer (nach einem Komma angeschlossen) für die Seitenzahl; wird nur auf eine Seitenzahl verwiesen, so ist dies durch ein vorgestelltes S. erkenntlich. Dieser Kennziffer ist unter Umständen der Name des Verfassers beigegeben, soweit dieser nicht aus dem Kontext eindeutig hervorgeht. Fußnoten im Text dienen der reinen Erläuterung oder Erweiterung des Haupttextes. Lediglich der Nachweis von Zitaten aus Zeitungsausschnitten erfolgt direkt in einer Fußnote. Beispiel: (Mann. 35,145) läßt sich über die Kennziffer 35 aufschlüs- seln als: Thomas Mann, Wagner und unsere Zeit. Aufsätze, Betrachtungen, Briefe. Frankfurt/M. 1983. S.145. Ausnahmen - Für folgende Werke wurden Siglen eingeführt: [GS] Richard Wagner, Gesammelte Schriften und Dichtungen in zehn Bän- den. Herausgegeben von Wolfgang Golther. Stuttgart 1914. Diese Ausgabe ist seitenidentisch mit der zweiten Auflage der "Gesammelten Schriften und Dichtungen" die Richard Wagner seit 1871 selbst herausgegeben hat. Golther stellte dieser Ausgabe lediglich eine Biographie voran und einen ausführlichen Anmerkungs- und Registerteil nach.