A Choral Conductor's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst La Ttéiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’S Preludes for Piano Op.163 and Op.179: a Musicological Retrospective

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst la ttÉiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’s Preludes for Piano op.163 and op.179: A Musicological Retrospective (3 Volumes) Volume 1 Adèle Commins Thesis Submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare 2012 Head of Department: Professor Fiona M. Palmer Supervisors: Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley & Dr Patrick F. Devine Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation to a number of people who have helped me throughout my doctoral studies. Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to my supervisors and mentors, Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Dr Patrick Devine, for their guidance, insight, advice, criticism and commitment over the course of my doctoral studies. They enabled me to develop my ideas and bring the project to completion. I am grateful to Professor Fiona Palmer and to Professor Gerard Gillen who encouraged and supported my studies during both my undergraduate and postgraduate studies in the Music Department at NUI Maynooth. It was Professor Gillen who introduced me to Stanford and his music, and for this, I am very grateful. I am grateful to the staff in many libraries and archives for assisting me with my many queries and furnishing me with research materials. In particular, the Stanford Collection at the Robinson Library, Newcastle University has been an invaluable resource during this research project and I would like to thank Melanie Wood, Elaine Archbold and Alan Callender and all the staff at the Robinson Library, for all of their help and for granting me access to the vast Stanford collection. -

SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN: Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com SirArthurSullivan ArthurLawrence,BenjaminWilliamFindon,WilfredBendall \ SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN: Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences. From the Portrait Pruntfd w 1888 hv Sir John Millais. !\i;tn;;;i*(.vnce$. i-\ !i. W. i ind- i a. 1 V/:!f ;d B'-:.!.i;:. SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN : Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences. By Arthur Lawrence. With Critique by B. W. Findon, and Bibliography by Wilfrid Bendall. London James Bowden 10 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, W.C. 1899 /^HARVARD^ UNIVERSITY LIBRARY NOV 5 1956 PREFACE It is of importance to Sir Arthur Sullivan and myself that I should explain how this book came to be written. Averse as Sir Arthur is to the " interview " in journalism, I could not resist the temptation to ask him to let me do something of the sort when I first had the pleasure of meeting ^ him — not in regard to journalistic matters — some years ago. That permission was most genially , granted, and the little chat which I had with J him then, in regard to the opera which he was writing, appeared in The World. Subsequent conversations which I was privileged to have with Sir Arthur, and the fact that there was nothing procurable in book form concerning our greatest and most popular composer — save an interesting little monograph which formed part of a small volume published some years ago on English viii PREFACE Musicians by Mr. -

Download Booklet

Silence & Music Booklet_Layout_5 final.indd 1 27/05/2017 12:02 recording Charterhouse School Chapel, Surrey 9-11 July 2016 recording producer Adrian Peacock balance engineer Neil Hutchinson editing Paul McCreesh, Adrian Peacock, David Hinitt All recording and editing facilities by Classic Sound Limited, London sources and publishers Stanford, The Blue Bird © 1910 Stainer & Bell Elgar, There is sweet music © 1908 Novello & Company Ltd Vaughan Williams, Silence and Music © 1953 Oxford University Press Howells, The summer is coming © 1965 Novello & Company Ltd Grainger, Brigg Fair © 1911 Schott & Company Vaughan Williams, Bushes and Briars © 1936 Novello & Company Ltd Vaughan Williams, The winter is gone © 1912 Novello & Company Ltd Vaughan Williams, The Turtle Dove © 1924 J Curwen & Sons MacMillan, The Gallant Weaver © 1997 Boosey & Hawkes Dove, Who killed Cock Robin? © 1995 Faber Music Grainger, The Three Ravens © 1950 Schott & Company Britten, The Evening Primrose © 1951 Boosey & Hawkes Warlock, All the flowers of the spring © 1923 Thames Publishing Elgar, Owls (An Epitaph) © 1908 Novello & Company Ltd Vaughan Williams, Rest © 1902 Bosworth & Company photography © Paul McCreesh image of paul mccreesh © Ben Wright cd series concept and design www.abrahams.uk.com Released under licence to Winged Lion www.wingedlionrecords.com Silence & Music Silence & Music Booklet_Layout_5 final.indd 2 27/05/2017 12:02 Silence & Music gabrieli consort paul mccreesh Silence & Music Booklet_Layout_5 final.indd 3 27/05/2017 12:02 programme 1 the blue bird -

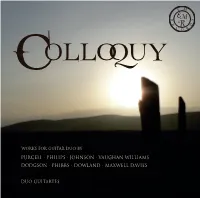

'Colloquy' CD Booklet.Indd

Colloquy WORKS FOR GUITAR DUO BY PURCELL · PHILIPS · JOHNSON · VAUGHAN WILLIAMS DODGSON · PHIBBS · DOWLAND · MAXWELL DAVIES DUO GUITARTES RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS (1872–1958) COLLOQUY 10. Fantasia on Greensleeves [5.54] JOSEPH PHIBBS (b.1974) Serenade HENRY PURCELL (1659–1695) 11. I. Dialogue [3.54] Suite, Z.661 (arr. Duo Guitartes) 12. II. Corrente [1.03] 1. I. Prelude [1.18] 13. III. Liberamente [2.48] 2. II. Almand [4.14] WORLD PREMIÈRE RECORDING 3. III. Corant [1.30] 4. IV. Saraband [2.47] PETER MAXWELL DAVIES (1934–2016) Three Sanday Places (2009) PETER PHILIPS (c.1561–1628) 14. I. Knowes o’ Yarrow [3.03] 5. Pauana dolorosa Tregian (arr. Duo Guitartes) [6.04] 15. II. Waters of Woo [1.49] JOHN DOWLAND (1563–1626) 16. III. Kettletoft Pier [2.23] 6. Lachrimae antiquae (arr. Duo Guitartes) [1.56] STEPHEN DODGSON (1924–2013) 7. Lachrimae antiquae novae (arr. Duo Guitartes) [1.50] 17. Promenade I [10.04] JOHN JOHNSON (c.1540–1594) TOTAL TIME: [57.15] 8. The Flatt Pavin (arr. Duo Guitartes) [2.08] 9. Variations on Greensleeves (arr. Duo Guitartes) [4.22] DUO GUITARTES STEPHEN DODGSON (1924–2013) Dodgson studied horn and, more importantly to him, composition at the Royal College of Music under Patrick Hadley, R.O. Morris and Anthony Hopkins. He then began teaching music in schools and colleges until 1956 when he returned to the Royal College to teach theory and composition. He was rewarded by the institution in 1981 when he was made a fellow of the College. In the 1950s his music was performed by, amongst others, Evelyn Barbirolli, Neville Marriner, the Philip Jones Brass Ensemble and the composer Gerald Finzi. -

Choir of St John's College, Cambridge Andrew Nethsingha

Choir of St John’S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE ANDREW NETHSINGHA Felix Mendelssohn, 1847 Mendelssohn, Felix Painting by Wilhelm Hensel (1794 – 1861) / AKG Images, London The Call: More Choral Classics from St John’s John Ireland (1879 – 1962) 1 Greater Love hath no man* 6:02 Motet for Treble, Baritone, Chorus, and Organ Alexander Tomkinson treble Augustus Perkins Ray bass-baritone Moderato – Poco più moto – Tempo I – Con moto – Meno mosso Douglas Guest (1916 – 1996) 2 For the Fallen 1:21 No. 1 from Two Anthems for Remembrance for Unaccompanied Chorus Slow Sir Charles Hubert Hastings Parry (1848 – 1918) 3 My soul, there is a country 4:00 No. 1 from Songs of Farewell, Six Motets for Unaccompanied Chorus Slow – Daintily – Slower – Animato – Slower – Tempo – Animato – Slower – Slower 3 Roxanna Panufnik (b. 1968) 4 The Call† 4:21 for Chorus and Harp For Andrew Nethsingha and the Choir of St John’s College, Cambridge Felix Mendelssohn (1809 – 1847) Hear my prayer* 11:21 Hymn for Solo Soprano, Chorus, and Organ Wilhelm Taubert gewidmet Oliver Brown treble 5 ‘Hear my prayer’. Andante – Allegro moderato – Recitativ – Sostenuto – 5:51 6 ‘O for the wings of a dove’. Con un poco più di moto 5:29 Sir Charles Hubert Hastings Parry 7 I was glad* 5:28 Coronation Anthem for Edward VII for Chorus and Organ Revised for George V Maestoso – Slower – Alla marcia 4 Sir Charles Villiers Stanford (1852 – 1924) 8 Beati quorum via 3:39 No. 3 from Three [Latin] Motets, Op. 38 for Unaccompanied Chorus To Alan Gray and the Choir of Trinity College, Cambridge Con moto tranquillo ma non troppo lento Sir John Tavener (1944 – 2013) 9 Song for Athene 5:31 for Unaccompanied Chorus Very tender, with great inner stillness and serenity – With resplendent joy in the Resurrection Sir Charles Villiers Stanford 10 Te Deum laudamus* 6:47 in B flat major • in B-Dur • en si bémol majeur from Morning, Communion, and Evening Services, Op. -

Review of Benjamin Britten, Sacred and Profane, AMDG, Five Flower Songs, Old French Carol, Choral Dances from Gloriana, Polyphony, Stephen Layton, Conductor

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Music Faculty Research School of Music 5-2003 Review of Benjamin Britten, Sacred and Profane, AMDG, Five Flower Songs, Old French Carol, Choral Dances From Gloriana, Polyphony, Stephen Layton, conductor. Hyperion, 2000 Vicki Stroeher Marshall University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/music_faculty Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Stroeher, Vickie. Review of Benjamin Britten, Sacred and Profane, AMDG, Five Flower Songs, Old French Carol, Choral Dances From Gloriana, Polyphony, Stephen Layton, conductor. Hyperion, 2001. Choral Journal 43 (May 2003): 59-63, 65. This Review of a Music Recording is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Music at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. MAY 2003 CHORAL JOURNAL <[email protected]> Benjamin Britten maturity. SacredAnd Profane • A.MD. G. Britten's choral works were composed most often to fulfill commissions, either RECORDING COMPANIES Five Flower Songs • OldFrench Carol THIS ISSUE ChoralDances From Gloriana from church choirs or individuals, or in the commemoration of specific occasions. Arts Music GmbH Polyphony, Stephen Layton, conductor Allegro, agent Recorded in Te mple Church, London, The Five Flower Songs (1950), the first 14134 NE Airport Way on October 6, 1999 and April 26 and 27, selections on the current disc, are a case Portland, OR 97230 in point. Britten composed these pieces 2000 Hyperion: CDA67140, ODD, Deutsche Grammophon 61'26 co honor Leonard and Dorothy Elmhirsc, Universal Classics Group, agent contributors to Britten's English Opera Worldwide Plaza Group, on the occasion of their silver 825 Eighth Avenue Editor's Note: Dr. -

English Song US 26/01/2005 11:00Am Page 28

557559-60 bk English Song US 26/01/2005 11:00am Page 28 O tell me the truth about love. The one whose sense suits Has it views of its own about money, ‘Mount Ephraim’ - Does it think Patriotism enough, And perhaps we should seem, Are its stories vulgar but funny? To him, in Death’s dream, ENGLISH SONG O tell me the truth about love. Like the seraphim. Your feelings when you meet it, I As soon as I knew 2 CDs featuring Vaughan Williams, Walton, Holst, Am told you can’t forget, That his spirit was gone I’ve sought it since 1 was a child I thought this his due, Stanford, Warlock, Bax, Quilter, Britten and others But haven’t found it yet; And spoke thereupon. I’m getting on for thirty-five, ‘I think,’ said the vicar, And still I do not know ‘A read service quicker What kind of creature it can be Than viols out-of-doors That bothers people so, In these frosts and hoars. Philip Langridge • Dame Felicity Lott • Simon Keenleyside That old-fashioned way When it comes, will it come without warning, Requires a fine day, Della Jones • Christopher Maltman • Anthony Rolfe Johnson just as I’m picking my nose, And it seems to me O tell me the truth about love. It had better not be.’ Will it knock on my door in the mornin Or tread in the bus on my toes, Hence, that afternoon, O tell me the truth about love. Though never knew he Will it come like a change in the weathe That his wish could not be, Will its greeting lie courteous or bluff, To get through it faster Will it alter my life altogether? They buried the master O tell me the truth about love. -

Program Notes for a Master's Recital in Choral Conducting Melissa Ann Williams Minnesota State University - Mankato

Minnesota State University, Mankato Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects 2013 Program Notes for a Master's Recital in Choral Conducting Melissa Ann Williams Minnesota State University - Mankato Follow this and additional works at: http://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Williams, Melissa Ann, "Program Notes for a Master's Recital in Choral Conducting" (2013). Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects. Paper 197. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. PROGRAM NOTES FOR A MASTER’S RECITAL IN CHORAL CONDUCTING By Melissa Ann Williams A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music In Choral Conducting Minnesota State University, Mankato Mankato, Minnesota May, 2013 Abstract PROGRAM NOTES FOR A MASTER’S RECITAL IN CHORAL CONDUCTING Melissa Ann Williams, M.M. Minnesota State University-Mankato, 2013. This document is presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Master of Music, and submitted in support of a choral concert conducted by the author on April 28, 2013 at 3:00 p.m. at St. Peter and Paul’s Catholic Church, Mankato, MN. It presents brief biographical information regarding each composer and a conductor’s analysis of their compositions performed in the concert. -

SULLIVAN PART Songs the LONG DAY CLOSES

SULLIVAN PART SONGS THE LONG DAY CLOSES KANTOS CHAMBER CHOIR | ELLIE SLORACH - CONDUCTOR 1. JOY TO THE VICTORS 1:42 2. THE BELEAGUERED 3:59 SULLIVAN 3. ECHOES 2:15 4. LEAD, KINDLY LIGHT 3:32 PART 5. SAY, WATCHMAN, WHAT OF THE NIGHT? 4:54 6. THROUGH SORROW’S PATH 2:22 SONGS 7. THE WAY IS LONG AND DREARY 4:37 8. IT CAME UPON THE MIDNIGHT CLEAR 4:40 THE LONG DAY CLOSES 9. I SING THE BIRTH 2:49 10. ALL THIS NIGHT BRIGHT ANGELS SING 2:29 KANTOS CHAMBER CHOIR 11. UPON THE SNOW-CLAD EARTH 4:46 ELLIE SLORACH - CONDUCTOR 12. THE LAST NIGHT OF THE YEAR 3:21 Venue: The Parish Church of 13. FAIR DAFFODILS 2:08 St. Paul, Heaton Moor, Stockport. 14. SEASIDE THOUGHTS 3:35 Dates: 17/18 July 2019. Producer and Editor: Mike Purton. 15. O HUSH THEE MY BABIE 4:16 Recording Engineer: David Coyle. Recorded at 24/96 resolution 16. THE RAINY DAY 2:09 Design: Hannah Whale, 17. WHEN LOVE AND BEAUTY 3:51 www.fruition-creative.co.uk. Cover image: Whispering Eve by Gilbert 18. WREATHS FOR OUR GRAVES 6:40 Foster, courtesy of Bridgeman Images 19. PARTING GLEAMS 3:40 We wish to thank the Ida Carroll Trust and the EVENING 4:10 20. Sir Arthur Sullivan Society for their 21. THE LONG DAY CLOSES 4:02 most generous financial assistance, enabling this wonderful project Total Playing Time: 76:56 to take place. 2 Arthur Sullivan, 1882 Moonshine Days with celebrities 3 REFLECTIONS ON ARTHUR SULLIVAN’S PART SONGS by Florian Csizmadia The part song was a genre which enjoyed great popularity in England in the nineteenth century. -

Changes in the Teaching of Folk and Traditional Music: Folkworks and Predecessors

Changes in the Teaching of Folk and Traditional Music: Folkworks and Predecessors Thesis M. Price Submitted in fulfilment of the degree of PhD Newcastle University November 2017 i Abstract Formalised folk music education in Britain has received little academic attention, despite having been an integral part of folk music practice since the early 1900s. This thesis explores the major turns, trends and ideological standpoints that have arisen over more than a century of institutionalised folk music pedagogy. Using historical sources, interviews and observation, the thesis examines the impact of the two main periods of folk revival in the UK, examining the underlying beliefs and ideological agendas of influential figures and organisations, and the legacies and challenges they left for later educators in the field. Beginning with the first revival of the early 1900s, the thesis examines how the initial collaboration and later conflict between music teacher and folk song collector Cecil Sharp, and social worker and missionary Mary Neal, laid down the foundations of folk music education that would stand for half a century. A discussion of the inter-war period follows, tracing the impact of wireless broadcasting technology and competitive music festivals, and the possibilities they presented for both music education and folk music practice. The second, post-war revival’s dominance by a radical leftwing political agenda led to profound changes in pedagogical stance; the rejections of prior practice models are examined with particular regard to new approaches to folk music in schools. Finally, the thesis assesses the ways in which Folkworks and their contemporaries in the late 1980s and onward were able to both adapt and improve upon previous approaches. -

And the Comic Operas of Gilbert & Sullivan

PIRATES, POLICEMEN, AND OTHER PATRIOTS: LATE VICTORIAN 'ENGLISHNESS' AND THE COMIC OPERAS OF GILBERT & SULLIVAN by MELANIE JEAN THOMPSON B.A. (Honours), McGill University, 1999 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of History) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA August 2001 © Meknie Jean Thompson, 2001 In presenting this thesis in partial folfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written peamission. Department of V^i'S'VoOj The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date A'Uglsr 31,g.C>6f Abstract Music and theatre have long played a particular - but hitherto rather neglected — role in the construction and articulation of national identity. This thesis takes a closer look at that role through an examination of the fourteen "Savoy operas" produced by librettist William S. Gilbert and composer Arthur S. Sullivan between the years 1871 and 1896. It explores the impact these operas had on the formation of a particular idea of 'Englishness' in the late 19th century. The Savoy operas were produced in the context of a larger cultural trend, a historical moment of collective self-examination in which English national identity was being renegotiated and redefined. -

The Madrigal

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 1-1930 The madrigal. Frank B. Martin University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Frank B., "The madrigal." (1930). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 910. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/910 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'I UNIVERSITY OF LOUISVILLE THE MADRIGAL. A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty Of the Graduate School Of the University of Louisville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of Master of Arts Department of English By FRANK B. lVlARTIN 1930 CONTENTS Chapter-. Pages. I The Foreign Madrigal 1 - 9. Ii II The English Madrigal 10 - 21. "i'" III The Etymology and structure 22 - 27. IV The Lyrics 28 - 41. V Composers 42 - 59. VI Recent Tendencies 60 - 64. Conclusions 65 - 67. .. Example of a-Madrigal 68 - 76. ~ Bibliography 77 - 79. .~ • • • THE FORKEGN MADR IGAL • • , CHAPTER I · . THE FOREIGN MADRIGAL The madrigal is the oldest of concerted • secular forms. It had its origin in northern Ita17, perhaps as early as the twelfth century. The early ..."i;'" compositions had none of the elaborate devices which characterize the madrigals of the sixteenth century.