How to Make Organisations More Innovative, Open Minded and Critical in Their Thinking and Judgment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Task-Based Taxonomy of Cognitive Biases for Information Visualization

A Task-based Taxonomy of Cognitive Biases for Information Visualization Evanthia Dimara, Steven Franconeri, Catherine Plaisant, Anastasia Bezerianos, and Pierre Dragicevic Three kinds of limitations The Computer The Display 2 Three kinds of limitations The Computer The Display The Human 3 Three kinds of limitations: humans • Human vision ️ has limitations • Human reasoning 易 has limitations The Human 4 ️Perceptual bias Magnitude estimation 5 ️Perceptual bias Magnitude estimation Color perception 6 易 Cognitive bias Behaviors when humans consistently behave irrationally Pohl’s criteria distilled: • Are predictable and consistent • People are unaware they’re doing them • Are not misunderstandings 7 Ambiguity effect, Anchoring or focalism, Anthropocentric thinking, Anthropomorphism or personification, Attentional bias, Attribute substitution, Automation bias, Availability heuristic, Availability cascade, Backfire effect, Bandwagon effect, Base rate fallacy or Base rate neglect, Belief bias, Ben Franklin effect, Berkson's paradox, Bias blind spot, Choice-supportive bias, Clustering illusion, Compassion fade, Confirmation bias, Congruence bias, Conjunction fallacy, Conservatism (belief revision), Continued influence effect, Contrast effect, Courtesy bias, Curse of knowledge, Declinism, Decoy effect, Default effect, Denomination effect, Disposition effect, Distinction bias, Dread aversion, Dunning–Kruger effect, Duration neglect, Empathy gap, End-of-history illusion, Endowment effect, Exaggerated expectation, Experimenter's or expectation bias, -

A Neural Network Framework for Cognitive Bias

fpsyg-09-01561 August 31, 2018 Time: 17:34 # 1 HYPOTHESIS AND THEORY published: 03 September 2018 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01561 A Neural Network Framework for Cognitive Bias Johan E. Korteling*, Anne-Marie Brouwer and Alexander Toet* TNO Human Factors, Soesterberg, Netherlands Human decision-making shows systematic simplifications and deviations from the tenets of rationality (‘heuristics’) that may lead to suboptimal decisional outcomes (‘cognitive biases’). There are currently three prevailing theoretical perspectives on the origin of heuristics and cognitive biases: a cognitive-psychological, an ecological and an evolutionary perspective. However, these perspectives are mainly descriptive and none of them provides an overall explanatory framework for the underlying mechanisms of cognitive biases. To enhance our understanding of cognitive heuristics and biases we propose a neural network framework for cognitive biases, which explains why our brain systematically tends to default to heuristic (‘Type 1’) decision making. We argue that many cognitive biases arise from intrinsic brain mechanisms that are fundamental for the working of biological neural networks. To substantiate our viewpoint, Edited by: we discern and explain four basic neural network principles: (1) Association, (2) Eldad Yechiam, Technion – Israel Institute Compatibility, (3) Retainment, and (4) Focus. These principles are inherent to (all) neural of Technology, Israel networks which were originally optimized to perform concrete biological, perceptual, Reviewed by: and motor functions. They form the basis for our inclinations to associate and combine Amos Schurr, (unrelated) information, to prioritize information that is compatible with our present Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel state (such as knowledge, opinions, and expectations), to retain given information Edward J. -

Safe-To-Fail Probe Has…

Liz Keogh [email protected] If a project has no risks, don’t do it. @lunivore The Innovaon Cycle Spoilers Differentiators Commodities Build on Cynefin Complex Complicated sense, probe, analyze, sense, respond respond Obvious Chaotic sense, act, categorize, sense, respond respond With thanks to David Snowden and Cognitive Edge EsBmang Complexity 5. Nobody has ever done it before 4. Someone outside the org has done it before (probably a compeBtor) 3. Someone in the company has done it before 2. Someone in the team has done it before 1. We all know how to do it. Esmang Complexity 5 4 3 Analyze Probe (Break it down) (Try it out) 2 1 Fractal beauty Feature Scenario Goal Capability Story Feature Scenario Vision Story Goal Code Capability Feature Code Code Scenario Goal A Real ProjectWhoops, Don’t need forgot this… Can’t remember Feature what this Scenario was for… Goal Capability Story Feature Scenario Vision Story Goal Code Capability Feature Code Code Scenario Goal Oops, didn’t know about Look what I that… found! A Real ProjectWhoops, Don’t need forgot this… Can’t remember Um Feature what this Scenario was for… Goal Oh! Capability Hmm! Story FeatureOoh, look! Scenario Vision Story GoalThat’s Code funny! Capability Feature Code Er… Code Scenario Dammit! Oops! Oh F… InteresBng! Goal Sh..! Oops, didn’t know about Look what I that… found! We are uncovering be^er ways of developing so_ware by doing it Feature Scenario Goal Capability Story Feature Scenario Vision Story Goal Code Capability Feature Code Code Scenario Goal We’re discovering how to -

John Collins, President, Forensic Foundations Group

On Bias in Forensic Science National Commission on Forensic Science – May 12, 2014 56-year-old Vatsala Thakkar was a doctor in India but took a job as a convenience store cashier to help pay family expenses. She was stabbed to death outside her store trying to thwart a theft in November 2008. Bloody Footwear Impression Bloody Tire Impression What was the threat? 1. We failed to ask ourselves if this was a footwear impression. 2. The appearance of the impression combined with the investigator’s interpretation created prejudice. The accuracy of our analysis became threatened by our prejudice. Types of Cognitive Bias Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_cognitive_biases | Accessed on April 14, 2014 Anchoring or focalism Hindsight bias Pseudocertainty effect Illusory superiority Levels-of-processing effect Attentional bias Hostile media effect Reactance Ingroup bias List-length effect Availability heuristic Hot-hand fallacy Reactive devaluation Just-world phenomenon Misinformation effect Availability cascade Hyperbolic discounting Recency illusion Moral luck Modality effect Backfire effect Identifiable victim effect Restraint bias Naive cynicism Mood-congruent memory bias Bandwagon effect Illusion of control Rhyme as reason effect Naïve realism Next-in-line effect Base rate fallacy or base rate neglect Illusion of validity Risk compensation / Peltzman effect Outgroup homogeneity bias Part-list cueing effect Belief bias Illusory correlation Selective perception Projection bias Peak-end rule Bias blind spot Impact bias Semmelweis -

Influence of Cognitive Biases in Distorting Decision Making and Leading to Critical Unfavorable Incidents

Safety 2015, 1, 44-58; doi:10.3390/safety1010044 OPEN ACCESS safety ISSN 2313-576X www.mdpi.com/journal/safety Article Influence of Cognitive Biases in Distorting Decision Making and Leading to Critical Unfavorable Incidents Atsuo Murata 1,*, Tomoko Nakamura 1 and Waldemar Karwowski 2 1 Department of Intelligent Mechanical Systems, Graduate School of Natural Science and Technology, Okayama University, Okayama, 700-8530, Japan; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Industrial Engineering & Management Systems, University of Central Florida, Orlando, 32816-2993, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-86-251-8055; Fax: +81-86-251-8055. Academic Editor: Raphael Grzebieta Received: 4 August 2015 / Accepted: 3 November 2015 / Published: 11 November 2015 Abstract: On the basis of the analyses of past cases, we demonstrate how cognitive biases are ubiquitous in the process of incidents, crashes, collisions or disasters, as well as how they distort decision making and lead to undesirable outcomes. Five case studies were considered: a fire outbreak during cooking using an induction heating (IH) cooker, the KLM Flight 4805 crash, the Challenger space shuttle disaster, the collision between the Japanese Aegis-equipped destroyer “Atago” and a fishing boat and the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant meltdown. We demonstrate that heuristic-based biases, such as confirmation bias, groupthink and social loafing, overconfidence-based biases, such as the illusion of plan and control, and optimistic bias; framing biases majorly contributed to distorted decision making and eventually became the main cause of the incident, crash, collision or disaster. -

Catalyzing Transformative Engagement: Tools and Strategies from the Behavioral Sciences

Catalyzing Transformative Engagement: Tools and Strategies from the Behavioral Sciences GoGreen Portland 2014 Thursday, October 16 ANXIETY AMBIVALENCE ASPIRATION ANXIETY ASPIRATIONAMBIVALENCE A Few of Our Clients Published online 11 April 2008 | Nature | doi:10.1038/news.2008.751 Your brain makes up its mind up to ten seconds before you realize it, according to researchers. By looking at brain acLvity while making a decision, the researchers could predict what choice people would make before they themselves were even aware of having made a decision. Source:Soon, C. S., Brass, M., Heinze, H.-J. & Haynes, J.-D. Nature Neurosci.doi: 10.1038/nn.2112 (2008). Cognive Bias • a paern of deviaon in judgment that occurs in parLcular situaons. • can lead to perceptual distorLon, inaccurate judgment, or illogical interpretaon. Source: www.princeton.edu Cogni&ve Biases – A Par&al List Ambiguity effect Framing effect Ostrich effect Anchoring or focalism Frequency illusion Outcome bias AOenLonal bias FuncLonal fixedness Overconfidence effect Availability heurisLc Gambler's fallacy Pareidolia Availability cascade Hard–easy effect Pessimism bias Backfire effect Hindsight bias Planning fallacy Bandwagon effect HosLle media effect Post-purchase raonalizaon Base rate fallacy or base rate neglect Hot-hand fallacy Pro-innovaon bias Belief bias Hyperbolic discounLng Pseudocertainty effect Bias blind spot IdenLfiable vicLm effect Reactance Cheerleader effect IKEA effect ReacLve devaluaon Choice-supporLve bias Illusion of control Recency illusion Clustering illusion Illusion -

To Err Is Human, but Smaller Funds Can Succeed by Mitigating Cognitive Bias

FEATURE | SMALLER FUNDS CAN SUCCEED BY MITIGATING COGNITIVE BIAS To Err Is Human, but Smaller Funds Can Succeed by Mitigating Cognitive Bias By Bruce Curwood, CIMA®, CFA® he evolution of investment manage 2. 2000–2008: Acknowledgement, where Diversification meant simply expanding the ment has been a long and painful plan sponsors discovered the real portfolio beyond domestic markets into T experience for many institutional meaning of risk. lesscorrelated foreign equities and return plan sponsors. It’s been trial by fire and 3. Post2009: Action, which resulted in a was a simple function of increasing the risk learning important lessons the hard way, risk revolution. (more equity, increased leverage, greater generally from past mistakes. However, foreign currency exposure, etc.). After all, “risk” doesn’t have to be a fourletter word Before 2000, modern portfolio theory, history seemed to show that equities and (!@#$). In fact, in case you haven’t noticed, which was developed in the 1950s and excessive risk taking outperformed over the there is currently a revolution going on 1960s, was firmly entrenched in academia long term. In short, the crux of the problem in our industry. Most mega funds (those but not as well understood by practitioners, was the inequitable amount of time and wellgoverned funds in excess of $10 billion whose focus was largely on optimizing effort that investors spent on return over under management) already have moved return. The efficient market hypothesis pre risk, and that correlation and causality were to a more comprehensive risk management vailed along with the rationality of man, supposedly closely linked. -

Cognitive Biases in Fitness to Practise Decision-Making

ADVICE ON BIASES IN FITNESS TO PRACTISE DECISION-MAKING IN ACCEPTED OUTCOME VERSUS PANEL MODELS FOR THE PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS AUTHORITY Prepared by: LESLIE CUTHBERT Date: 31 March 2021 Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................................. 2 Background .................................................................................................. 2 Purpose of the advice.................................................................................... 3 Summary of conclusions ................................................................................ 4 Documents considered .................................................................................. 4 Technical terms and explanations ................................................................... 5 Disclaimer .................................................................................................... 5 II. How biases might affect the quality of decision-making in the AO model, as compared to the panel model .............................................................................. 6 Understanding cognitive biases in fitness to practise decision-making ............... 6 Individual Decision Maker (e.g. a Case Examiner) in AO model ......................... 8 Multiple Case Examiners .............................................................................. 17 Group Decision Maker in a Panel model of 3 or more members ....................... 22 III. Assessment of the impact of these biases, -

Cost Risk Estimating Management Glossary

Cost Risk Estimating Management Glossary 2021 The beginning of wisdom is the definition of terms. Socrates (470 – 399 BCE) Theorem 1: 50% of the problems in the world result from people using the same words with different meanings. Theorem 2: the other 50% comes from people using different words with the same meaning. S. Kaplan (1997) Abbreviations AACE Association for the Advancement of Cost Engineering International (AACE International) ® ® CEVP Cost Estimate Validation Process FHWA Federal Highway Administration FRA Federal Railroad Administration FTA Federal Transit Administration FY Fiscal Year ISO International Organization for Standardization GSP General Special Provisions PMBOK™ Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMI's PMBOK) Third Edition PMI Project Management Institute Combined Standards Glossary ROD Record of Decision Revenue Operations Date (FTA) TAG Transportation Analysis Group TDM Transportation Demand Management TPA Transportation Partnership Act (Washington State Program of Projects) TRAC Transportation Center (WSDOT research center) TSM Transportation System Management A accountability The quality or state of being accountable; especially: an obligation or willingness to accept (12) responsibility or to account for one's actions. The person having accountability for responding, monitoring and controlling risk is the risk manager. accuracy The difference between the forecasted value and the actual value (forecast accuracy). (16) accuracy range An expression of an estimate's predicted closeness to final actual costs or time. Typically (1) Dec expressed as high/low percentages by which actual results will be over and under the 2011 estimate along with the confidence interval these percentages represent. See also: Confidence Interval; Range. activity A component of work performed during the course of a project. -

Taxonomies of Cognitive Bias How They Built

Three kinds of limitations Three kinds of limitations Three kinds of limitations: humans A Task-based Taxonomy of Cognitive Biases for Information • Human vision ️ has Visualization limitations Evanthia Dimara, Steven Franconeri, Catherine Plaisant, Anastasia • 易 Bezerianos, and Pierre Dragicevic Human reasoning has limitations The Computer The Display The Computer The Display The Human The Human 2 3 4 Ambiguity effect, Anchoring or focalism, Anthropocentric thinking, Anthropomorphism or personification, Attentional bias, Attribute substitution, Automation bias, Availability heuristic, Availability cascade, Backfire effect, Bandwagon effect, Base rate fallacy or Base rate neglect, Belief bias, Ben Franklin effect, Berkson's ️Perceptual bias ️Perceptual bias 易 Cognitive bias paradox, Bias blind spot, Choice-supportive bias, Clustering illusion, Compassion fade, Confirmation bias, Congruence bias, Conjunction fallacy, Conservatism (belief revision), Continued influence effect, Contrast effect, Courtesy bias, Curse of knowledge, Declinism, Decoy effect, Default effect, Denomination effect, Magnitude estimation Magnitude estimation Color perception Behaviors when humans Disposition effect, Distinction bias, Dread aversion, Dunning–Kruger effect, Duration neglect, Empathy gap, End-of-history illusion, Endowment effect, Exaggerated expectation, Experimenter's or expectation bias, consistently behave irrationally Focusing effect, Forer effect or Barnum effect, Form function attribution bias, Framing effect, Frequency illusion or Baader–Meinhof -

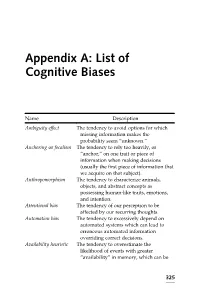

List of Cognitive Biases

Appendix A: List of Cognitive Biases Name Description Ambiguity effect The tendency to avoid options for which missing information makes the probability seem “unknown.” Anchoring or focalism The tendency to rely too heavily, or “anchor,” on one trait or piece of information when making decisions (usually the first piece of information that we acquire on that subject). Anthropomorphism The tendency to characterize animals, objects, and abstract concepts as possessing human-like traits, emotions, and intention. Attentional bias The tendency of our perception to be affected by our recurring thoughts. Automation bias The tendency to excessively depend on automated systems which can lead to erroneous automated information overriding correct decisions. Availability heuristic The tendency to overestimate the likelihood of events with greater “availability” in memory, which can be 325 Appendix A: (Continued ) Name Description influenced by how recent the memories are or how unusual or emotionally charged they may be. Availability cascade A self-reinforcing process in which a collective belief gains more and more plausibility through its increasing repetition in public discourse (or “repeat something long enough and it will become true”). Backfire effect When people react to disconfirming evidence by strengthening their belief. Bandwagon effect The tendency to do (or believe) things because many other people do (or believe) the same. Related to groupthink and herd behavior. Base rate fallacy or The tendency to ignore base rate Base rate neglect information (generic, general information) and focus on specific information (information only pertaining to a certain case). Belief bias An effect where someone’s evaluation of the logical strength of an argument is biased by the believability of the conclusion. -

Selective Exposure Theory Twelve Wikipedia Articles

Selective Exposure Theory Twelve Wikipedia Articles PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Wed, 05 Oct 2011 06:39:52 UTC Contents Articles Selective exposure theory 1 Selective perception 5 Selective retention 6 Cognitive dissonance 6 Leon Festinger 14 Social comparison theory 16 Mood management theory 18 Valence (psychology) 20 Empathy 21 Confirmation bias 34 Placebo 50 List of cognitive biases 69 References Article Sources and Contributors 77 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 79 Article Licenses License 80 Selective exposure theory 1 Selective exposure theory Selective exposure theory is a theory of communication, positing that individuals prefer exposure to arguments supporting their position over those supporting other positions. As media consumers have more choices to expose themselves to selected medium and media contents with which they agree, they tend to select content that confirms their own ideas and avoid information that argues against their opinion. People don’t want to be told that they are wrong and they do not want their ideas to be challenged either. Therefore, they select different media outlets that agree with their opinions so they do not come in contact with this form of dissonance. Furthermore, these people will select the media sources that agree with their opinions and attitudes on different subjects and then only follow those programs. "It is crucial that communication scholars arrive at a more comprehensive and deeper understanding of consumer selectivity if we are to have any hope of mastering entertainment theory in the next iteration of the information age.