Cross-Border Co-Operation Between the Kaliningrad Oblast and Poland in the Context of Polish-Russian Relations in 2004–2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Captive Island Kaliningrad Between MOSCOW and the EU

41 A CAPTIVE ISLAND KAlInIngRAD bETWEEn MOSCOW AnD ThE EU Jadwiga Rogoża, Agata Wierzbowska-Miazga, Iwona Wiśniewska NUMBER 41 WARSAW JULY 2012 A CAPTIVE ISLAND KALININGRAD BETWEEN MOSCOW AND THE EU Jadwiga Rogoża, Agata Wierzbowska-Miazga, Iwona Wiśniewska © Copyright by Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich im. Marka Karpia / Centre for Eastern Studies CONTENT EDITORS Adam Eberhardt, Marek Menkiszak EDITORS Katarzyna Kazimierska, Anna Łabuszewska TRANSLATION Ilona Duchnowicz CO-OPERATION Jim Todd GRAPHIC DESIGN PARA-BUCH CHARTS, MAP, PHOTOGRAPH ON COVER Wojciech Mańkowski DTP GroupMedia PuBLISHER Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich im. Marka Karpia Centre for Eastern Studies ul. Koszykowa 6a, Warsaw, Poland Phone + 48 /22/ 525 80 00 Fax: + 48 /22/ 525 80 40 osw.waw.pl ISBN 978–83–62936–13–7 Contents KEY POINTS /5 INTRODUCTION /8 I. KALININGRAD OBLAST: A SUBJECT OR AN OBJECT OF THE F EDERATION? /9 1. THE AMBER ISLAND: Kaliningrad today /9 1.1. Kaliningrad in the legal, political and economic space of the Russian Federation /9 1.2. Current political situation /13 1.3. The current economic situation /17 1.4. The social situation /24 1.5. Characteristics of the Kaliningrad residents /27 1.6. The ecological situation /32 2. AN AREA UNDER SPECIAL SURVEILLANCE: Moscow’s policy towards the region /34 2.1. The policy of compensating for Kaliningrad’s location as an exclave /34 2.2. The policy of reinforcing social ties with the rest of Russia /43 2.3. The policy of restricted access for foreign partners to the region /45 2.4. The policy of controlling the region’s co-operation with other countries /47 3. -

Why Kaliningrad Region?

Kaliningrad region Government NEW OPPORTUNITIES FOR BUISNESS DEVELOPMENT GENERAL INFORMATION MAXIMUM LENGTH NORWAY OF THE TERRITORY SWEDEN ESTONIA 108 КМ 108 LATVIA RUSSIA KALININGRAD LITHUANIA 15.1 REGION 205 КМ THS КМ² REGION IRELAND TERRITORY BELARUS ADMINISTRATIVE CENTER GERMANY POLAND 22 ENGLAND CITIES KALININGRAD >480 CHECH UKRAINE THOUSAND PEOPLE SLOVAKIA AUSTRIA MAIN CITIES FRANCE HUNGARY SOVETSK BALTIYSK SWITZERLAND ROMANIA >40K PEOPLE >36K PEOPLE CHERNYAKHOVSK GUSEV ITALY >37K PEOPLE >28K PEOPLE SVETLOGORSK >22K PEOPLE SPAIN BULGARIA PORTUGALPORRTUGALR Kaliningrad region Government GREECE POPULATION 60% WORKING-AGE POPULATION > 1 MIL PEOPLE DATED 01/08/2018 >10 THOUSAND PEOPLE PER YEAR >4.5 MIGRATION THOUSAND 5.2% GROWTH GRADUATES ANNUALLY UNEMPLOYMENT RATE >66 PEOPLE PER KM2 13 POPULATION DENSITY HIGHER EDUCATION 12TH PLACE IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION INSTITUTIONS Kaliningrad region Government ECONOMIC 524 $ 102 $ PERFORMANCE 33 536 ₶ 6 579 ₶ PER MONTH М2 PER YEAR AVERAGE SALARY RENTAL PRIСE FOR COMMERCIAL AND OFFICE 10.2 PROPERTIES BN $ 0.06 $ 400 $ 3.7 25 800 ₶ 641.58 BN ₶ kWh PER YEAR FOREIGN TRADE ELECTRICITY PRICE INTERNET PRICE TURNOVER 0.02 $ 2018 1.2 ₶ PER MIN OUTGOING CALLS 7. 2 2.08 0.74 $ 48 ₶ BN $ BN $ PER LITER 417.4 BN ₶ 130.5 BN ₶ PRICE OF GASOLINE GROSS INVESTMENTS CAPITAL REGIONAL DONE BY PRODUCT ORGANIZATIONS 2017 2018 Kaliningrad region Government SPECIAL ECONOMIC ZONE >129 1 BN ₶ MIL ₶ SEZ REGIME COVERS 2 BN $ 0.02 MIL $ THE WHOLE REGION SEZ REGIME IS REGULATED TOTAL AMOUNT MINIMUM BY THE REGIONAL AUTHORITIES -

Kaliningrad Study

Kaliningrad in Europe Kaliningrad in Europe A study commissioned by the Council of Europe Edited by Mr Bartosz Cichocki Linguistic Editing œ Mr Paul Holtom, Mrs Catherine Gheribi This study has been drafted by a group of independent experts at the initiative of the Committee of Advisers on the Development of Transfrontier Co-operation in Central and Eastern Europe, an advisory body established by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe. Although every care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this study, the Council of Europe takes no responsibility for factual errors or omissions. The views expressed in the study are those of the authors and do not commit the Council of Europe or any of its organs. Factual information correct at March 2003. © Council of Europe, 2003 Foreword Walter Schwimmer Secretary General of the Council of Europe Kaliningrad, the city and the Oblast, are these days receiving a lot of attention from international circles. The Russian Federation has been actively raising the awareness of European institutions about the peculiar situation of the region, separated by mainland Russia and surrounded by land by two countries, Lithuania and Poland, soon-to- become members of the European Union. The perspective of the enlargement of the European Union to the Russia‘s exclave immediate neighbours is raising fears that the isolation of the Oblast would deepen and its economic and social backwardness worsen. The Council of Europe has responded to these legitimate preoccupation by taking recently several initiatives. In 2002, the Parliamentary Assembly held a thorough debate which led to the adoption of Recommendation 1579 on the Enlargement of the European Union and the Kaliningrad Region. -

The Euro-Atlantic Integration and the Future of Kaliningrad Oblast

NATO EURO-ATLANTIC PARTNERSHIP COUNCIL INDIVIDUAL RESEARCH FELLOWSHIPS 2000 - 2002 PROGRAMME THE EURO-ATLANTIC INTEGRATION AND THE FUTURE OF KALININGRAD OBLAST by Česlovas Laurinavičius Vilnius - 2002 1 CONTENT Abstract 3 Aim of the Research 4 Methodology 8 1. Main tendencies of Russia’s foreign policy after the collapse of the Soviet Union 9 2. NATO enlargement and Kaliningrad 11 2.1. Military transit of the Russian Federation through the territory of the Republic of 13 Lithuania: historic and political science profile 2.2. Circumstances of the Soviet military withdrawal from the Republic of Lithuania: 15 Negotiations Process 2.3. 1994-1995 negotiations between Vilnius and Moscow over military transit 18 agreement 2.4. Regulation of the military transit of the Russian Federation through the territory of 27 Lithuania and its practical execution 2.5. Intermediate conclusion 29 3. The impact assessment of the EU enlargement on the Kaliningrad oblast 30 3.1. Relations between Moscow and Kaliningrad 30 3.2. The trends of the social, economical and political development in the Kaliningrad 35 oblast of the Russian Federation 3.3. The EU acquis communautaire, the applicant countries and Kaliningrad: issue 37 areas 3.4. Perspectives of the crisis prevention 45 Conclusions 50 2 ABSTRACT The collapse of the Soviet Union has given impetus to the debate about the future of the Kaliningrad Oblast (KO) of the Russian Federation. The main cause for this is the fact that concrete exclave of the Russian Federation – which is the country’s westernmost outpost – has been left cut off from Russia by Lithuania and Poland and surrounded by countries that are orienting themselves toward the European Union and NATO. -

UTLC ERA: Trans Eurasian Railway Container Operator IBS Web Talk

TCEA22 (C) 2021 ERA UTLC UTLC ERA: Trans Eurasian railway container operator IBS Web talk Alexey Grom General Manager 10/06/2021 UTLC ERA BASE TRANSIT ROUTES Kaliningrad up close Baltiysk KCSP Dzerzhinskaya-Novaya Chernyakhovsk Vyartsilya Mamonovo Zheleznodorozhniy Buslovskaya Kaliningrad Bruzgi Svislach Brest Dostyk Izov Altynkol 5-DAY UTLC ERA SERVICES UTLC ERA organizes regular container trains through Cargo flows to/from EU Cargo flows to/from China Belarus, Russia and Kazakhstan NEW GLOBAL LOGISTICS At the apex of the pandemic: air and sea • Air total cargo volumes down by >40%. • Air rates up >300%. • Up to 20% of sea sailings cancelled, total volumes down by 10-15%. • W-BOUND sea freight rates up >20%. • E-BOUND sea freight rates jumped twofold. Impact of the pandemic: rail • The “Modal Shift” phenomena – goods switching over to rail – is set to have a lasting effect on the industry, leading to us to a state of the “New Global Logistics” • "New Global Logistics" – is a paradigm shift which reflects the growing role of rail in trans-Eurasian trade • Previously, trans-Eurasian railway container transportation was expected to settle at around 3-4% of EU- China trade, but this figure already exceeded 5%, hence the status-quo is no more TREMENDOUS GROWTH OF TRANSEURASIAN TRANSIT Absolute 2019 2020 % Change Figures for UTLC ERA change Cargo volumes 333 021 546 902 213 881 64% transported, TEU Results of goods shifting over to rail: • Absolute growth of 214k TEU transported in 2020 over 2019, which amounts to 64% increase. • The total $ value of goods transported by UTLC ERA in 2020 exceeded $30 billion, accounting for 5.4% of trade between China and Europe. -

Why Kaliningrad Region?

Kaliningrad region Government NEW OPPORTUNITIES FOR BUISNESS DEVELOPMENT GENERAL INFORMATION MAXIMUM LENGTH NORWAY OF THE TERRITORY SWEDEN ESTONIA 108 КМ 108 LATVIA RUSSIA KALININGRAD LITHUANIA 15.1 REGION 205 КМ THS КМ² REGION IRELAND TERRITORY BELARUS ADMINISTRATIVE CENTER GERMANY POLAND 22 ENGLAND CITIES KALININGRAD >480 CHECH UKRAINE THOUSAND PEOPLE SLOVAKIA AUSTRIA MAIN CITIES FRANCE HUNGARY SOVETSK BALTIYSK SWITZERLAND ROMANIA >40K PEOPLE >36K PEOPLE CHERNYAKHOVSK GUSEV ITALY >37K PEOPLE >28K PEOPLE SVETLOGORSK >22K PEOPLE SPAIN BULGARIA PORTUGALPORRTUGALR Kaliningrad region Government GREECE POPULATION 56.5% WORKING-AGE POPULATION > 1 MIL PEOPLE DATED 01/08/2018 ~13 THOUSAND PEOPLE > . PER YEAR 3 7 MIGRATION THOUSAND 4. % GROWTH GRADUATES 4 ANNUALLY UNEMPLOYMENT RATE >67 PEOPLE PER KM2 9 POPULATION DENSITY HIGHER EDUCATION 12TH PLACE IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION INSTITUTIONS Kaliningrad region Government ECONOMIC 556 $ 88 $ PERFORMANCE 39 661 ₶ 6 579 ₶ 2 PER MONTH М PER YEAR AVERAGE SALARY RENTAL PRIСE FOR COMMERCIAL AND OFFICE 10.3 PROPERTIES BN $ 0.08 $ 347 $ 5.8 25 800 ₶ BN ₶ 670 kWh PER YEAR FOREIGN TRADE ELECTRICITY PRICE INTERNET PRICE TURNOVER 0.02 $ 1.2 ₶ PER MIN OUTGOING CALLS 7.1 1.6 0.65 $ 48 ₶ BN $ BN $ PER LITER 460,9 BN ₶ BN ₶ PRICE 103 OF GASOLINE GROSS INVESTMENTS CAPITAL REGIONAL DONE BY PRODUCT ORGANIZATIONS Kaliningrad region Government SPECIAL ECONOMIC ZONE >128.4 1 BN ₶ MIL ₶ SEZ REGIME COVERS BN $ 0.02 MIL $ THE WHOLE REGION >1.7 SEZ REGIME IS REGULATED TOTAL AMOUNT MINIMUM BY THE REGIONAL AUTHORITIES OF DECLARED -

A New European Union Policy for Kaliningrad Occasional Papers

Occasional Papers March 2002 n°33 Sander Huisman A new European Union policy for Kaliningrad published by the European Union Institute for Security Studies 43 avenue du Président Wilson F-75775 Paris cedex 16 phone: + 33 (0) 1 56 89 19 30 fax: + 33 (0) 1 56 89 79 31 e-mail: [email protected] www.iss-eu.org In January 2002 the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) became a Paris-based autonomous agency of the European Union. Following an EU Council Joint Action of 20 July 2001, it is now an integral part of the new structures that will support the further development of the CFSP/ESDP. The Institute’s core mission is to provide analyses and recommendations that can be of use and relevance to the formulation of EU policies. In carrying out that mission, it also acts as an interface between experts and decision-makers at all levels. The ISS-EU is the successor to the WEU Institute for Security Studies, set up in 1990 by the WEU Council to foster and stimulate a wider discussion across Europe. Occasional Papers are essays or reports that the Institute considers should be made avail- able as a contribution to the debate on topical issues relevant to European security. They may be based on work carried out by researchers granted awards by the ISS, on contribu- tions prepared by external experts, and on collective research projects or other activities organised by (or with the support of) the Institute. They reflect the views of their authors, not those of the Institute. -

The Effect of Railway Network Evolution on the Kaliningrad Region's Landscape Environment Romanova, Elena; Vinogradova, Olga; Kretinin, Gennady; Drobiz, Mikhail

www.ssoar.info The effect of railway network evolution on the Kaliningrad region's landscape environment Romanova, Elena; Vinogradova, Olga; Kretinin, Gennady; Drobiz, Mikhail Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Romanova, E., Vinogradova, O., Kretinin, G., & Drobiz, M. (2015). The effect of railway network evolution on the Kaliningrad region's landscape environment. Baltic Region, 4, 137-149. https://doi.org/10.5922/2074-9848-2015-4-11 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Free Digital Peer Publishing Licence This document is made available under a Free Digital Peer zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den DiPP-Lizenzen Publishing Licence. For more Information see: finden Sie hier: http://www.dipp.nrw.de/lizenzen/dppl/service/dppl/ http://www.dipp.nrw.de/lizenzen/dppl/service/dppl/ Diese Version ist zitierbar unter / This version is citable under: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-51411-4 E. Romanova, O. Vinogradova, G. Kretinin, M. Drobiz This article addresses methodology of THE EFFECT OF RAILWAY modern landscape studies from the NETWORK EVOLUTION perspective of natural and man-made components of a territory. Railway infras- ON THE KALININGRAD tructure is not only an important system- REGION’S LANDSCAPE building element of economic and settle- ENVIRONMENT ment patterns; it also affects cultural landscapes. The study of cartographic materials and historiography made it possible to identify the main stages of the * development of the Kaliningrad railway E. Romanova , network in terms of its territorial scope and O. Vinogradova*, to describe causes of the observed changes. * Historically, changes in the political, eco- G. -

Discussion on the Vistula Lagoon Regional Development Considering

OCEANOGRAPHY No. 114,2012 Discussion on the Vistula Lagoon regional development considering local consequences of climate changes Interim report on the ECOSUPPORT BONUS+ project "Advanced modelling tool for scenarios of the Baltic Sea ECOsystem to SUPPORT decision making" and RFBR project No. 08-05-92421 Anastasia Domnina, Boris Chubarenko Atlantic Branch of P.P Shirhov Institute of Oceanology of Russian Academy of Sciences, Kaliningrad, Russia Front: Map of the municipalities around the Vistula Lagoon ISSN: 0283-7714 © SMHI OCEANOGRAPHY No 114,2012 Discussion on the Vistula Lagoon regional development considering local consequences of climate changes Interim report on the ECOSUPPORT BONUS+ project "Advanced modelling tool for scenarios of the Baltic Sea ECOsystem to SUPPORT decision making" and RFBR project No. 08-05-92421 Anastasia Domnina, Boris Chubarenko Atlantic Branch of P.P Shirhov Institute of Oceanology of Russian Academy of Sciences, Kaliningrad, Russia, [email protected], [email protected] Summary Information about natural and economic conditions in the Vistula lagoon together with directions of development of municipalities around the lagoon is presented in the report. The review of directions of development show that all municipalities aim to develop tourism, harbours and land transport. Moreover, Polish municipalities give large attention to environmental protection. In the future the development towards these strategic directions will continue together with an increased role of environmental protection and consequences of climate changes. Assessment of tolerance of Vistula Lagoon municipalities’ development strategies to climate changes have shown that directions of Polish municipalities’ development is less tolerant to consequences of climate change because of a large area disposed to possible flooding, and therefore possibly high expenses for prevention of territory flooding. -

Königsberg–Kaliningrad, 1928-1948

Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg–Kaliningrad, 1928-1948 By Nicole M. Eaton A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Yuri Slezkine, chair Professor John Connelly Professor Victoria Bonnell Fall 2013 Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg–Kaliningrad, 1928-1948 © 2013 By Nicole M. Eaton 1 Abstract Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg-Kaliningrad, 1928-1948 by Nicole M. Eaton Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Yuri Slezkine, Chair “Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg-Kaliningrad, 1928-1948,” looks at the history of one city in both Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Russia, follow- ing the transformation of Königsberg from an East Prussian city into a Nazi German city, its destruction in the war, and its postwar rebirth as the Soviet Russian city of Kaliningrad. The city is peculiar in the history of Europe as a double exclave, first separated from Germany by the Polish Corridor, later separated from the mainland of Soviet Russia. The dissertation analyzes the ways in which each regime tried to transform the city and its inhabitants, fo- cusing on Nazi and Soviet attempts to reconfigure urban space (the physical and symbolic landscape of the city, its public areas, markets, streets, and buildings); refashion the body (through work, leisure, nutrition, and healthcare); and reconstitute the mind (through vari- ous forms of education and propaganda). Between these two urban revolutions, it tells the story of the violent encounter between them in the spring of 1945: one of the largest offen- sives of the Second World War, one of the greatest civilian exoduses in human history, and one of the most violent encounters between the Soviet army and a civilian population. -

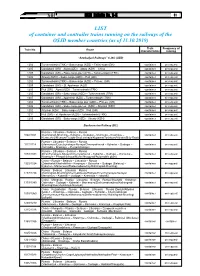

LIST of Container and Contrailer Trains Running on the Railways of the OSJD Member Countries (As of 11.10.2019)

2019 OSJD Bulletin No. 5-6 91 LIST of container and contrailer trains running on the railways of the OSJD member countries (as of 11.10.2019) Train Frequency of Train No. Route characteristics running “Azerbaijani Railways” CJSC (AZD) 1202 Turkmenbashi (TRK) – Baku-cargo (AZD) – Tbilisi-node (GR) container on request 1205 Gardabani (GR) – Alyat (AZD) – Aktau (KZH) – China container on request 1207 Gardabani (GR) – Baku-cargo pier (AZD) – Turkmenbashi (TRK) container on request 1202 Almaty (KZH) – Baku-cargo (AZD) – Poti (GR) container on request 1202 Turkmenbashi (TRK) – Baku-cargo (AZD) – Poti-ex. (GR) container on request 1209 Gardabani (GR) – St. Apsheron (AZD) container on request 1205 Poti (GR) – Alyat (AZD) – Turkmenbashi (TRK) container on request 1205 Gardabani (GR) – Baku-cargo (AZD) – Turkmenbashi (TRK) container on request 1207 Gardabani (GR) – Apsheron (AZD) – Turkmenbashi (TRK) container on request 1202 Turkmenbashi (TRK) – Baku-cargo pier (AZD) – Poti-ex. (GR) container on request 1205 Gardabani (GR) – Baku-cargo pier ex. (AZD) – Altynkol (KZH) container on request 1202 Altynkol (KZH) – Baku-cargo (AZD) – Poti (GR) container on request 1211 Poti (GR) – st. Apsheron (AZD) – Turkmenbashi (TRK) container on request 1205 Gardabani (GR) – Baku-cargo (AZD) – Almaty (KZH) container on request Byelorussian Railway (BC) Russia – Lithuania – Belarus – Russia 1022/1021 (Kaliningrad-Shunting – Kybartai – Gudogai – Osinovka – Krasnoye – container on request Kuntsevo-2/Moscow-Freight-Smolenskaya/Kupavna/Tuchkovo/Vorsino/Bely Rast) Russia -

Kaliningrad Anniversary: the First Steps of Georgy Boos 123 KALININGRAD ANNIVERSARY: the FIRST STEPS of GEORGY BOOS*

Kaliningrad Anniversary: the First Steps of Georgy Boos 123 KALININGRAD ANNIVERSARY: THE FIRST STEPS OF GEORGY BOOS* Raimundas Lopata Introduction The origin and originality of the problem often referred to as- theKalin ingrad puzzle are geopolitical. Their concise description could be as follows. The part of Prussia taken by the Soviet Union after the Second World War was transformed into a gigantic Soviet military base. It performed the func- tions of the exclave against the West and of the barrier which helped the USSR to ensure the dependence of the Eastern Baltics and domination in Poland. After the Cold War, the territory of 15,100 square kilometres with a population of almost a million, owned by Russia and located the farthest to the West, although on the Baltic Sea, ashore became isolated from the motherland and turned into an exclave. Gradually that exclave found itself at the crossroads of different security structures and later – surrounded by one of them. Changes in the situation gave rise to the so-called Kaliningrad dis- course, i.e. political decisions influenced by international policies in Central and Eastern Europe and academic discussion and studies of the role of this Russian-owned exclave in the relations of the East and the West. The academic literature reveals quite a broad panorama of interpretations of this topic. It should be pointed out that the issues which appeared atop of the research – how the collapse of the USSR affected the situation of the Ka- liningrad Oblast, what it would be in the future, what role would be played by the motherland and the neighbours, what influence it would experience from the Euro-Atlantic development to the East, how the international community should help the Oblast to adapt to the changing environment, etc.